1. Acknowledgements

Basis Social would like to wholeheartedly thank the many people who contributed to this research project.

At the FSA, this includes Sophie Watson and Harriet Pickles in the Social Science team within the Analytics Unit for their advice on the research design and analysis, as well as Aimee Harmer, Robyn Smyth and Taryn Davey from the Food Policy Division for their policy advice.

Two external experts also contributed to the research design and analysis. Julie Barnett, Professor of Health Psychology at the University of Bath, is thanked for her guidance on consumer needs and behaviours regarding allergen communication when eating out. Rob Waller, an expert in information design, is thanked for his advice on the principles and practices for effective written communication.

Representatives from the following organisations are thanked for giving their time to attend the expert co-creation workshops:

-

Allergy Action

-

Allergy UK

-

Anaphylaxis UK

-

British Beer and Pub Association

-

Coeliac UK

-

Nationwide Caterers Association

-

UK Hospitality

-

University College London

-

University of Central Lancashire

-

University of Sheffield

Finally, a huge thanks to the many consumers with food hypersensitivities who contributed to the research, as well as the three food businesses who generously allowed us to test the prototype communication materials in their premises.

2. Executive Summary

Overview

In December 2023, the Food Standards Agency (FSA) commissioned Basis Social to conduct research to improve how Food Business Operators (FBO) use written communications to communicate about allergens to consumers with food hypersensitivity ((FHS)- allergies or intolerances to food or those who have coeliac disease).

The research had two aims, which were to provide:

-

evidence-based principles on the ways in which FBOs can improve the design and delivery of their written communications which 1) prompt consumers to disclose their allergies and intolerances and 2) provide allergen information to consumers.

-

evidence-based, user-tested designs of 1) a sign prompting consumers to disclose if they have a FHS[1] and 2) allergen information communication that could be used on written materials (including menus, labels and allergen matrices) to indicate which, if any, of the 14 regulated allergens are present.

The research employed an iterative approach inspired by design thinking. The logic of this approach was to start with FHS consumer needs, to develop principles for written communications that address those needs, and to understand what works for executing those principles in the context of signs, menus, labels and matrices. Methods used included an evidence review, co-creation workshops with FHS consumers and experts (including industry representatives, allergy charities, allergy experts, behavioural scientists), and digital and in-situ testing of prototype signs, menus, labels and matrices with FHS consumers.

This report presents the findings from the research. Key findings are summarised below.

1. Evidence-based principles on the ways in which FBOs can improve the design and delivery of their written communications

Written allergen communications must be responsive to three core FHS consumer needs: safety, confidence in the FBO’s ability to meet their FHS needs safely, and as close to normal eating out experience as possible. To meet these needs, the research identified two sets of principles.

Principles relating to written communications to encourage disclosure:

-

Salient– the communication is effective in getting FHS consumers to notice and pay attention to the message.

-

Clear– the communication provides a clear call to action, so consumers understand what is required of them.

-

Simple– the communication is concise, uses straightforward language and gets to the point.

-

Empathetic– the communication demonstrates that the FBO understands and will be able to meet FHS consumer needs (including safety, confidence and normality).

-

Motivating– the communication provides a reason for why it is important to disclose, or reduces barriers to motivation, for example by demonstrating that staff will react constructively and sensitively.

Principles relating to written communications indicating the presence of allergens in a dish:

-

Clear– the communication provides a clear indication of what allergens are present in dishes/products.

-

Easy to use– the communication makes it easy for FHS consumers to identify dishes/products that are safe for them to eat.

-

Comprehensive– the communication should indicate which of any of the 14 allergens are present, as opposed to just a subset.

-

Consistent– the communication uses a standardised system for communicating the presence of allergens. From an FHS consumers’ perspective, one universal system is preferable as it means they do not need to learn multiple systems. At the very least, an FBO should use the same system for all its communications.

-

Accurate– This is a property of how written information is checked and maintained, and so relates less to the execution of the information itself.

3. Design of a sign and written allergen information communication to indicate presence of allergens

The below findings reflect participants’ preferences, rather than what is measurably effective and which considers the needs of the FBO.

Sign encouraging consumer disclosure of FHS

For signs encouraging disclosure, consumers’ most preferred message was:

- Please talk to us if you have a food allergy, intolerance or coeliac disease. We want to cater safely for everyone.

The message was simple and clear – both in terms of language and the need for FHS consumers to disclose. Additionally, consumers viewed the message ‘we want to cater safely for everyone’ as warm, inclusive, and empathetic.

The research suggested that additional messages highlighting the risks of relying solely on written allergen information can, in some instance, motivate FHS consumers to disclose their FHS. Based on this small-scale qualitative study, the two messages we tested were perceived as potentially effective:

-

Our menu descriptions do not contain all ingredients and we may sometimes have to substitute ingredients.

-

Our food is prepared in a kitchen where allergens are present.

However, there was a tension between the principle of motivation and simplicity. Some FHS consumers felt the additional text served to complicate disclosure messages, potentially reducing their effectiveness. Further research would be helpful to investigate whether an additional motivational message makes consumers more likely to disclose.

The timing of the message was also identified as a factor for behaviour change. FHS consumers said that messages seen at the moment when making a food choice (for example, when reviewing a menu) were more likely to prompt disclosure.

Logos were generally preferred to a plain sign. While consumers preferred the FSA’s logo overall, this was because it implied a FBO had been accredited. As this is not the case its use could lead to unintended consequences of misplaced confidence in the FBO. Using a business logo was interpreted as the FBO taking allergen communication seriously. Other ‘iconic’ graphic elements, for example a megaphone to signify the need for a consumer to talk and a heart to show a business caring, were tested and rejected in the ideation stage, as they distracted from the message.

Beyond a need for simplicity, FHS consumers did not discuss the graphic design of a sign in depth and how it could be made salient. Further research is recommended here.

Written allergen information communicating presence of allergens

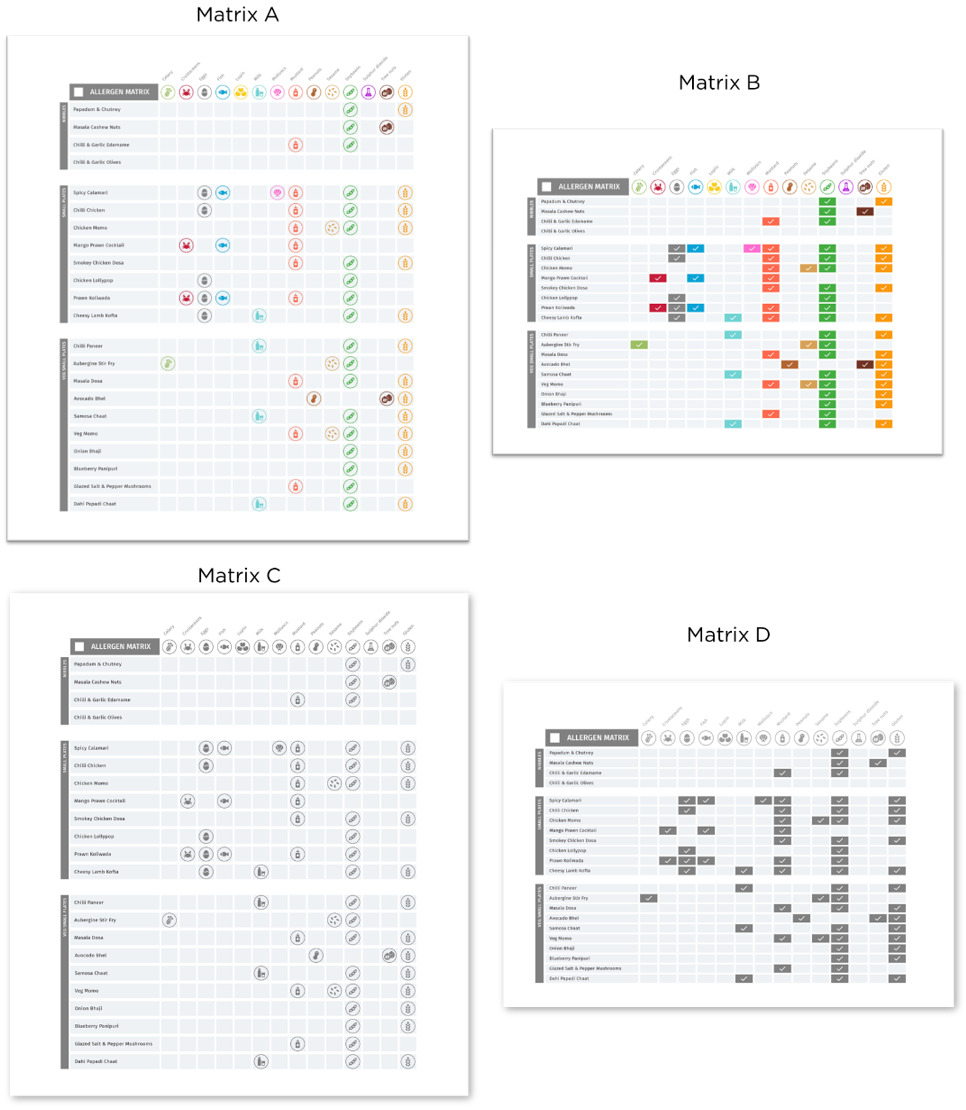

There were two main systems developed to communicate the presence of allergens in a dish: icons and emboldened text. Figure 1 shows the icons designs developed through the research. While both systems work, consumers had different preferences for which system is most clear and usable across different communication materials.

For menus, online and in-situ tests generated slightly different findings. Consumers taking part in online testing sessions preferred emboldened text. However, during the in-situ tests, consumers who used the systems to make food choices, said that both emboldened text and icons worked well in practice.

As a system for communicating allergen information, consumers saw emboldened text as clear and straightforward. Emboldened text also does not require consumers to use a legend or decipher the meaning of an icon, reducing cognitive load. However, during in-situ tests, consumers saw icons as having the advantage of enabling them to quickly scan the menu and find a dish that was safe to eat.

For labels used on signs to identify products, consumers preferred coloured icons with the accompanying text in bold underneath, with the only icons displayed corresponding to those present in a product. This execution was seen as clear and easy to use – mainly as the coloured icon was eye-catching and the allergen name was listed under each icon, reducing the risk of misinterpretation.

For matrices, consumers thought coloured icons worked better than ticks, as it was easier to read and identify the allergen, without needing to look back to the icon label at the top of the page. However, some FHS consumers also questioned whether icons would be universally recognised and understood by all FHS consumers, indicating risks of misinterpretation. If colour is removed, then ticks were perceived as easier to read.

Considering user-tested designs within the wider system

Effective written allergen communication enables FBOs to meet FHS consumer needs. However, signs, menus, labels and matrices are not a silver bullet. Rather, these communications materials should be understood as part of a wider system, all parts of which need to function effectively to meet FHS consumer needs. Based on this research, this system includes the need for:

-

FBO staff to have the capability (skills and knowledge) and opportunity (time) to effectively communicate with FHS customers, and to be motivated by beliefs to take FHS seriously and knowledge about the allergens present in a dish.

-

FBOs to put in place processes and systems for allergen management and communication.

-

FBOs to provide additional information on allergen management practices to consumers, for example a website.

Verbal allergen communication also forms a key part of the wider system. Although the principles developed in this study relate primarily to written communication, several may reasonably be applied to verbal communication. For example, verbal communications are likely to benefit from being clear, simple, empathetic, motivating, accurate, comprehensive and consistent. However, verbal communication comprises additional elements (for example, body language) that have not been considered in this research. Consequently, this research does not provide guidance on how to execute these principles for verbal communication. Further research may be useful for exploring how this should be achieved verbally, and if any other principles are warranted for verbal communication of allergen information.

This research was led primarily by FHS consumer needs. While industry experts and FBOs did participate at key stages, it would be valuable to explore the useability and feasibility of the designs with FBOs in more depth. For example, recruiting FBOs for in-situ testing was a significant challenge. This was due primarily to the difficulty finding FBOs whose existing written communication materials (in particular, menus) could be adapted easily and quickly to reflect the prototype designs.

Several FBOs were unable to participate in in-situ testing because of difficulties updating their existing written allergen information to reflect the prototypes. This included FBOs whose menus were very complex or contained incomplete allergen information. While the total number of FBOs approached for this research was small, the difficulties experienced for recruitment to test the materials in situ are revealing. They underscore the range of ways in which FBOs may struggle to adapt to a more standardised approach to communicate allergen information through written communications. Consequently, the research recommends further work to explore the feasibility of the user-tested designs with FBOs.

3. Introduction and background

Food hypersensitivity (FHS) includes food allergy, intolerance, and coeliac disease and affects over 3% of people in the UK.[2] It is a significant health issue that has extensive impacts on quality of life and mental health, causing stress, depression, and anxiety.[3] [4] Food allergies can also lead to hospitalisation - there were over 30,000 hospital admissions related to a food induced anaphylaxis between 1998-2018, with an annual increase of 5.7%. However, the percentage of fatalities has decreased from 0.7% to 0.19% over the same period.[5]

The Food Standards Agency (FSA) is responsible for allergen labelling and is seeking to make improvements to help people with FHS make safe, informed decisions when purchasing non-prepacked food. This is food which is sold loose, or which is packed or cooked and served to order, for example, takeaway food and food served in restaurants and cafés.

Currently, if a Food Business Operator (FBO) sells or provides food to customers directly, for example in a restaurant, they must provide allergen information. This can be done in a number of ways including:

-

written allergen information such as on a menu, chalkboard or in an information pack such as an allergen matrix.

-

Verbally with a written notice placed in a clearly visible position explaining how customers can obtain this information - for example by speaking to a member of staff.

Regulations[6] impose a duty on FBOs to ensure that all mandatory food allergen information (relating to 14 substances listed in the Food Information to Consumers Regulation that are known to cause allergies) is accurate, available, and easily accessible to the consumer. To enable this, FBOs need to have the skills and knowledge to provide accurate allergen information and manage allergens effectively.

Research conducted for the FSA on the needs and preferences of FHS consumers when eating out, as well as with FBOs on allergen management and communication practices, has highlighted that while both parties want eating out or buying takeaway food to be a safe and positive experience for FHS consumers, there are differing views as how best to achieve this.[7]

For example, some FHS consumers are keen to have a ‘normal’ dining experience and make decisions about the food they eat by relying on written information, with minimal necessity to initiate a conversation with staff. Meanwhile, some FBOs want to work with customers to find the right options for them, which requires a conversation, so food can be prepared safely and any risk of allergen cross contamination managed.

The FSA are keen to encourage consumers to inform staff that they have a FHS requirement and make them feel comfortable asking for allergen information. Additionally, the allergen information provided to consumers needs to be clear, easy and accessible so they can make an informed choice when deciding what to eat.

This research focused on in-person experiences of FHS consumers ordering loose food at micro, small and medium sized (SME) food business’.

The aims of this research are to provide:

-

evidence-based principles on the ways in which FBOs can improve the design and delivery of their written communications which 1) prompt consumers to disclose their allergies and 2) provide allergen information to consumers.

-

evidence-based, user-tested designs of: 1) a sign prompting consumers to disclose if they have a FHS and 2) allergen information communication that could be used on written materials (e.g. menus, labels) to indicate which, if any, of the 14 regulated allergens are present.

To help meet these aims, the following research questions were identified.

-

What do consumers need from communications during different types of interaction or points of contact with a food business?[8]

-

What is and isn’t working for the current methods of communication (written and verbal) at each touchpoint (including message, design, delivery, timing in consumer journey, placement), considering consumer needs?

-

What does previous research and theory (e.g. behavioural, communications, design) recommend for effective communication?

-

What are the ways in which FBOs can improve the design and delivery of their communications on allergen information to consumers when they are eating out, to ensure that they are effective and meet the needs of consumers?

4. Methodology

Overview of approach

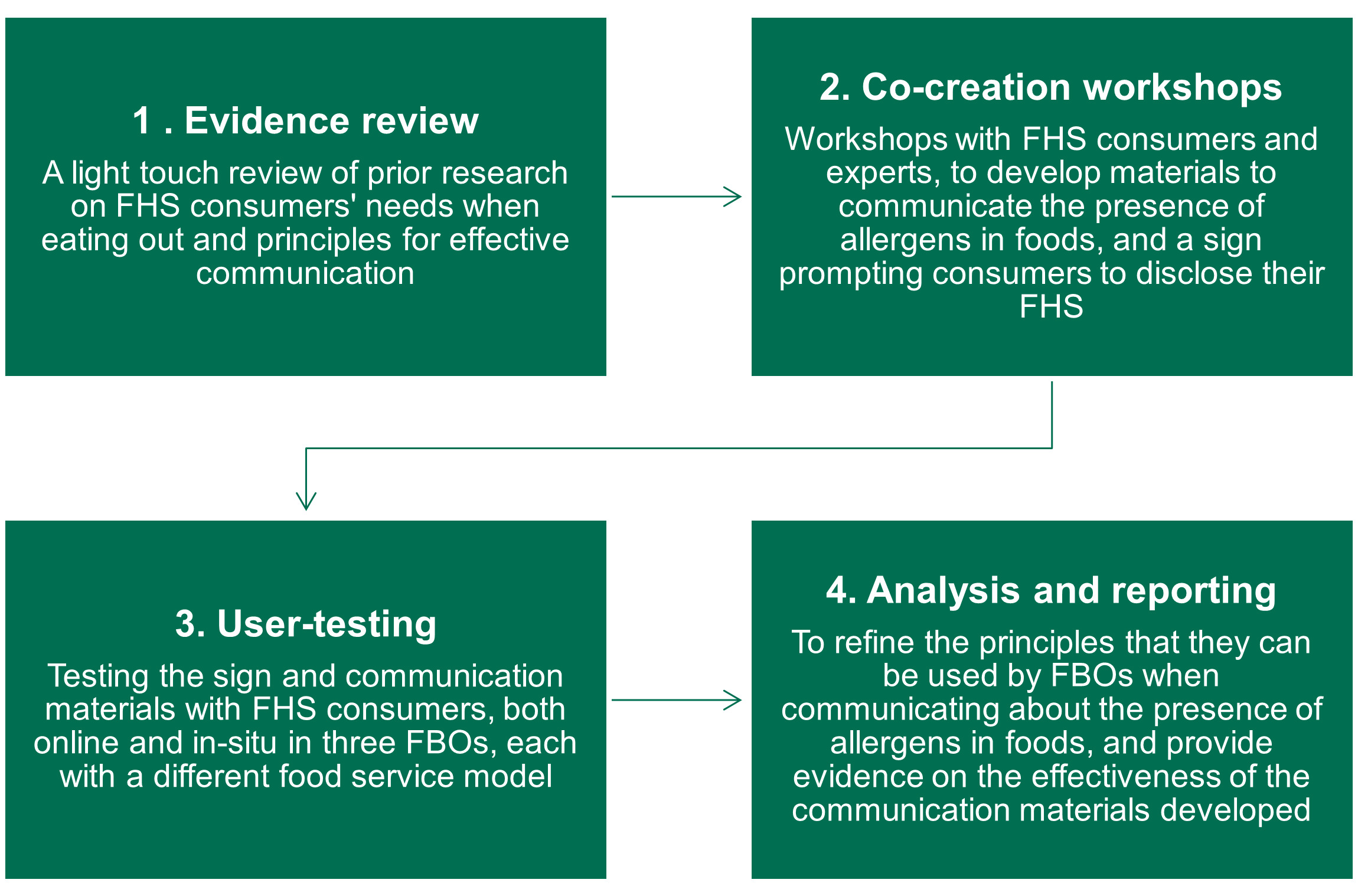

The overall approach for the research was inspired by design thinking,[9] an iterative and human-centred method used in this context to understand the needs of FHS consumers, identify problems in current allergen communication and create innovative communication materials to prototype and test. The method involved four stages, shown in Figure 2.

Communication principles were developed across each research stage. The principles were initially presented as a working list and refined as consumers discussed how they used different assets (for example, signs and menus) in practice. Specifically, the four types of communication material considered were:

-

Signs requesting consumers to disclose their FHS

-

Menus

-

Labels

-

Allergen matrices

While the research design involved industry trade bodies in workshops and some FBO interviews, overall, the research was consumer-led. Further work is needed to understand whether these materials are workable for FBOs.

Finally, it should be noted that the approach was iterative and involved the team learning and adapting the methods as challenges emerged. The limitation of the methods, as well as challenges faced are discussed in greater depth below.

A summary of each stage is now provided. For full methodological details of each stage, please refer to the technical report.

Stage 1: Evidence review

The first stage of the research involved a review of published evidence and internal FSA work related to allergen communication and the needs of FHS consumers when eating out. The review also conducted a light touch analysis of effective communication practice, with a focus on insights from the behavioural sciences. In total, 32 documents were analysed, mainly centred on prior research undertaken for the FSA (see Appendix A).

The aim of the evidence review was to provide:

-

A draft set of principles concerning the effective design and delivery of FBO written allergen communications, to be iterated through primary research.

-

The allergen communication needs and challenges faced by FHS consumers and FBOs, using a customer journey map of eating out.

-

Personas to bring to life these needs for different FHS consumers and FBOs.

The outputs from the evidence review were used as stimulus to inform the co-creation process. The customer journey map and personas are provided in Appendix B.

Stage 2: Co-creation workshops

Introduction

The co-creation workshops aimed to develop ideas and prototype communication materials against the principles of food allergen communication identified through the evidence review.

The co-creation process involved two sub-stages.

-

Stage 2A involved developing ideas to prototype the following communication materials:

-

A sign, prompting consumers to disclose if they have a FHS

-

Allergen information communication that could be used on written materials (e.g. menus/ labels/matrices) to indicate which, if any, of the 14 regulated allergens are present.

-

-

Stage 2B involved refining the prototype communication materials.

Each stage had two workshops: one with 14 experts (including industry representatives, allergy charities, allergy experts, behavioural scientists) and one with 13 consumers who have FHS (selected to cover a range of FHS types and severities as well as demographic characteristics) – see Table 1 for a breakdown. Additionally, 4 designers attended each workshop to support the creation process. Sample details are provided in Appendix C.

Each stage is now discussed in more depth.

Stage 2A: Developing ideas for communication materials

The first workshops were held face-to-face and generated ideas for the communication materials. The expert workshop took place on the 18th January 2024 and the consumer workshop on the 20th January 2024. Each workshop lasted 3 hours.

The workshops aimed to immerse participants in the topic area and the communication needs of FHS consumers and FBOs when eating out. Participants were presented with a range of information which they were asked to discuss and comment on. This included:

-

a FHS customer journey when eating out, based on previous research

-

the needs of FHS consumers and FBOs as expressed through personas

-

real-life examples of:

-

menus, labels and matrices with allergen information on them

-

allergen disclosure signs

-

Participants were also presented with a working list of principles for effective allergen communication. Participants were asked to use these principles, and consider the needs of FHS consumers and FBOs, during an adapted version of the ideation exercise called “Crazy 8s”. For this exercise, participants were asked to sketch four distinct ideas in eight minutes, in response to a specific challenge (for example, how to communicate allergen information to consumers). The activity was designed to produce as many ideas as possible, rather than focus on the quality of ideas. Participants then prioritised ideas at the end of the workshop.

The ideas generated through the crazy 8s exercise and through wider workshop discussions were used to identify broad themes for what was important to participants. Prototypes of signage, menus, matrices and label options (see Appendix D) were then designed with these needs in mind.

Stage 2B: Refining the prototype communication materials

The second workshops were held online and aimed to gather insight on how to further develop and refine the prototype communication materials. The expert workshop took place on the 6th February 2024 and the consumer workshop on the 7th February 2024. Both workshops lasted 2 hours.

Workshop participants were presented with a variety of executions of different communication materials (see Table 2). Participants were asked about their immediate reactions to each execution, before reviewing them in greater depth in terms of the extent to which they met the principles for allergen communication.

Appendix D includes an image of all the prototypes tested in the online workshops.

Developing the final prototypes for testing

Following the workshops, a thematic analysis was conducted to identify the principles of effective communication arising from the evidence review and co-creation sessions. The prototypes that were preferred by workshop participants were optimised considering the principles and participants’ feedback from the session. A final set of prototypes was taken forward for user testing (see Appendix E).

Stage 3: User testing

Introduction

User testing aimed to explore FHS consumer views about how easy different prototypes were to use, and which prototypes they preferred. The prototypes tested are shown in Appendix E. An overview of these prototypes in provided in Table 3, below.

User testing comprised two sub-stages.

-

Stage 3A involved testing the prototypes on a digital platform with 33 FHS consumers.

-

Stage 3B involved testing the prototypes live in 3 food business settings with 18 FHS consumers.

-

The food businesses were selected to have different service models, as follows:

-

A restaurant with table service

-

A café with counter service

-

A market stall

-

-

Interviews with the FBOs were also conducted to understand their experience of using the prototypes.

Stage 3A: Digital testing

The aim of the digital testing was to undertake a detailed exploration of FHS consumers preferences on the communication prototypes. This included:

-

Consumers’ immediate reactions, thoughts and feelings to each communications prototype

-

How easy consumers thought it would be to use the communication prototypes

-

How consumers viewed and would improve the disclosure messages on the communications prototypes, including their likelihood to disclose their FHS

-

How consumers viewed, and would improve, the design features on the communications prototypes, including the use of logos, icons, or written allergens

Note that as these questions were explored online, responses reflect participant’s beliefs about how they would behave and what would be useful. They do not provide insight into how participants would actually behave if presented with the prototypes during a real-life eating out experience.

Digital testing was undertaken using an online engagement platform (Howspace). Testing took place between 27th February and 5th March and involved 33 consumers with a range of FHS (including different food allergies, intolerances and coeliac disease), of varying severities, and with different demographic characteristics (see Appendix F for sample details and Table 4 for a breakdown). Each participant completed a total of three tasks, the first two lasting 25 minutes each, and the third lasting 10 minutes.

Consumers were divided into four groups of approximately equal size. Consumers in each group were shown example prototypes and then asked a series of questions about them. Private responses were collected, and there was no group discussion concerning the prototypes. Given the number of prototypes developed, different prototypes were shown to each group (see Table 5 below and refer to Appendices D and E for prototype executions). The digital testing discussion guide is provided in the Technical Report.

Tasks undertaken by FHS consumers during the testing included:

-

Using the platform annotation tools to mark up the communication materials to indicate what design features they liked or did not like.

-

Open text questions, for example asking consumers why they thought prototypes were effective/ineffective, what they liked/disliked about different design features, and how to improve message wording on disclosure signs.

-

Asking participants to describe step by step how they would use prototypes.

-

Responding to hypothetical scenarios, for example showing images of different eating out settings (e.g. a restaurant, café and market stall) and considering how communication prototypes might work in each setting.

-

Using a survey function to vote on their preferred executions of a prototype (e.g. the ease of use of menus designed using emboldened text versus icons).

Alongside the main prototypes (signs, menus, labels and matrices) developed and tested through this research, the digital testing stage also gathered participants’ responses to ideas for digital communications. These ideas focused on menus and matrices that used a filtering system so that FHS consumers could exclude unsafe options.

Stage 3B: In-situ testing

The aim of the in-situ testing was to explore how FHS consumers respond to and use the prototype communication materials (a sign, a label and a menu) when ordering food at a food business. This included:

-

Whether consumers noticed the allergen disclosure sign.

-

Where noticed, whether the sign encouraged a consumer to disclose their FHS requirements.

-

How easy consumers found using labels or menus with either emboldened text or icons to indicate the presence of allergens in a dish.

-

How environmental factors influenced the use of the allergen communication materials (for example, busyness of the food business, the role of waiting staff, differences in food service model).

-

How FHS consumers believed the communication materials could be improved, accounting for these environmental factors.

In-situ testing was undertaken in 3 food business settings, each with a different food service model:

-

A restaurant using table service. The main prototypes tested at the restaurant included a menu that used icons and a disclosure sign.

-

A café using counter service. The main prototypes tested at the café included a menu and food labels, both of which used emboldened text, and a disclosure sign.

-

A market stall. The main prototypes tested at the market stall were food labels that used icons and a disclosure sign.

As part of these interviews, participants were shown the other prototypes that had been developed and asked to compare them to the prototypes they had seen and used during the in-situ tests.

Table 6 provides an overview of what prototypes were tested in each setting. For each food business, their existing labels and/or menus were re-designed with either icons or emboldened text along with a disclosure notice. In all other respects, the re-designed materials were made to look like the FBO’s current menu or label design.[10] A different FHS disclosure sign was also tested in each food business, using the prototype designs created during the co-creation session. Only the market stall currently used a disclosure sign.

In total, 18 FHS consumers took part in the in-situ testing (6 per food business). FHS consumers were recruited to a range of demographic characteristics. However, to minimise safety risks, only consumers with a mild or moderate FHS were involved in the in-situ tests (and those with severe food allergies or coeliac disease were excluded). Sample details are provided in Table 7 below.

The in-situ testing involved accompanied consumer observations and interviews. Specifically, researchers either ate a meal with FHS consumers in the restaurant or café or accompanied them buying products from the market stall.

To minimise the influence of the research design on behaviours, FHS consumers were initially not made aware that the purpose of the research was to test prototypes of communication materials; rather they were told the research team were interested in observing their experiences of eating out. After food was ordered and provided, researchers explained that the purpose of the research was to test prototype communication materials.

During the in-situ tests, interviews were conducted using a semi-structured discussion guide. These guides were adapted for each FBO, based on their service model and prototypes tested.

As well as using their redesigned menu or label prototypes to serve participating FHS consumers, FBOs were encouraged (but not required) to use the prototypes as part of the regular service with other consumers, so long as they were comfortable doing so. This was adopted in the café and the market stall. However, this was not possible in the restaurant, due to a last-minute replacement a dish on the menu.[11] FBO’s also took part in a follow-up interview to get their feedback on using the prototypes.

As far as possible, FBOs were asked to replicate their normal service process when using the prototypes. No guidance about how the prototypes should be used was provided. FBOs were free to place the disclosure sign where they felt best, and to use written communication prototypes (labels and menus) in line with their standard practice. The only additional request was for FBOs to give participating consumers the opportunity to disclose their FHS themselves, without being verbally prompted. This was to avoid participants being prompted to disclose before they had the chance to respond to the prototypes. If participants had not disclosed their FHS, servers were free to engage in any verbal allergen communication that they usually would. As a safety precaution, FBOs and service staff were made aware in advance that the consumers accompanying the researcher had an FHS.

Stage 4: Analysis and reporting

Each stage of the research involved a different analytical process. These are summarised in Table 8 below. Full details of the analysis process can be found in the technical report.

The final report draws together and integrates findings across each of the stages, with a focus on the following two areas.

The first concerns principles of effective communication. As mentioned, a working list of principles was developed from the evidence review. This list was refined following the co-creation workshops. During the user testing stage, the list was further simplified and refined in terms of how written communications are used in practice, and which principles matter most to FHS consumers in this context.

The second concerns views on the use and effectiveness of the written communications materials. Analysis for this part of the report predominantly focuses on the user testing stages, though findings from co-creation workshops are included – for example, to provide insight into why early-stage prototypes were rejected.

Methodological limitations and learnings

The research method had several limitations, as well as learnings that arose through the research process. These are summarised below, and further thoughts on implications are provided in Chapter 7.

Evidence review stage

There was little published evidence on the effectiveness of written and verbal allergen communication. What research there is tends to focus on FHS consumer needs, preferences and challenges when eating out, and consequently principles were derived from these. A limitation of this approach was that principles could:

-

conflict with FBOs needs or be unworkable in practice for FBOs.

-

risk unintended consequences.

-

be subjective and vary across consumers.

For example, some FHS consumers expressed a desire for greater autonomy to make their own decisions about the food they eat when eating out, and to rely on information in a menu to do this. In practice this may not be possible, as FBOs cannot provide all allergen information necessary to make a safe choice in a menu (for instance, due to allergen cross contact risk when the food was prepared). Other consumers preferred a conversation with an FBO rather than to rely on written information. Additionally, these needs would also change in different food business settings.

Co-creation stage

While signage and written communications are important, they are only part of how FHS consumers experience a food venue and assess whether food is safe to eat. For example, the recommendations from friends, customer reviews, look and feel of the food business setting, and the knowledge and proactive communication by staff also have a very important role to play. The research did not focus on the full customer journey, and consequently it was not possible to explore the interrelationship between different elements of communications.

Further, there were cases where the views of experts and FHS consumers diverged significantly. For example, when ideating around what types of signage would be most effective for disclosure, some experts recommended signage modelled on public health warning signs, for example using colour palettes that signified risk. This view was not shared by FHS consumers. Such differences underscore the complexity of developing written communications which work for all stakeholders.

User testing stage

The digital testing involved discussing the signage and communication prototypes ex-situ. This meant questions had to be framed around hypothetical scenarios and asking FHS consumers to imagine using the materials in a café, restaurant or market stall. Consequently, understanding how the prototypes may be used in real life, along with behavioural implications (for example, whether a sign would encourage disclosure) is likely to be limited through this approach.

Ideas for digital communications were only tested during digital testing. As all participants in digital testing were, of necessity, able to participate online, this means that these ideas were not tested with digitally excluded groups.

For the in-situ tests, to minimise safety risks, recruitment of FHS consumers was limited to those with mild or moderate FHS only. FHS consumers with more severe FHS may have responded differently. Further, recruiting FBOs was a significant challenge. This was due primarily to finding FBOs whose existing written communication prototypes (in particular, menus) could be adapted easily and quickly to reflect the prototype designs. For example:

-

some FBOs had menus with a very large number of dishes and lacked the space to use icons or emboldened text. Using these menus for the tests would require them to be completely redesigned.

-

some FBOs used menus which were perceived to provide incomplete or inaccurate allergen information (for example, because the ingredients listed suggested allergens were present that were not indicated by icons), making the job of updating them resource intensive and increasing risks to participants.

-

one FBO mainly used a digital menu, which was technically complex to update with the prototype designs. In this food business setting, the paper menu was not kept up to date and hence not suitable for the research.

While the total number of FBOs approached for this research was small, the difficulties experienced for recruitment are revealing. They underscore the range of ways in which FBOs may struggle to adapt to a more standardised approach to communicate allergen information through written communications. This is discussed in Chapter 9.

5. FHS consumer and FBO needs and principles for allergen communication

Introduction

This section provides an overview of the needs of FHS consumers and FBOs for allergen communication at different touchpoints when eating out. Needs were initially established from the evidence review, and then iterated and refined based on the co-creation workshops. Relevant findings from the user-testing are also reported in this section, however, the outcomes of this stage of the research are discussed in more detail in Chapter 6.

It should be noted that there was relative limited insight from the evidence review on what works in terms of specific executions of allergen communications (for example, in terms of messages, design, delivery, timing in consumer journey, and placement). However, prior research does provide a wealth of insights into factors which may limit the effectiveness of written and verbal allergen communications for satisfying consumer needs. These insights were useful for informing initial principles for effective communication.

In the next section, overall consumer and FBO needs are summarised, before needs at each touchpoint are illustrated through a customer map.

FHS consumer needs

This research identified three core FHS consumer needs. All three have been highlighted by previous research and emerged as dominant themes during co-creation workshops with FHS consumers:

-

Safety: FHS consumers need to be able to make informed decisions about whether an FBO can accommodate their FHS and what dishes are safe for them to eat[12].

-

Confidence in the FBO: FHS consumers need to feel confident that an FBO takes their FHS seriously, is capable of catering to their needs, and has provided the correct information for them to make a safe choice about what to eat[13].

-

As normal an eating out experience as possible: FHS consumers want a ‘normal’ dining experience[14]. From the co-creation workshops, normal means to be treated like other customers and avoiding negative emotional situations (such as them being made to feel embarrassed or singled out) related to their FHS.

What is and isn’t working for the current methods of communication?

How needs are currently satisfied

Co-creation workshops and interviews with FHS consumers during the user testing stage highlighted a variety of behaviours performed by FHS consumers to satisfy core needs. These included:

-

To ensure safety, disclosing their FHS to servers, checking written allergen information (both pre-arrival and while in a food establishment), and confirming (either through written or verbal communication) that a dish has been prepared safely.

-

To ensure confidence, observing FBO staff, written allergen communications and the physical environment (including, for example, how busy an establishment is) to form judgements about whether an FBO takes FHS needs seriously and is likely to be able to cater for them effectively.

-

To ensure a normal dining experience, doing research in advance (for example, online or by contacting a food business) to figure out what is safe to eat, and/or opting not to disclose to a member of staff and instead relying on written information or their prior knowledge of dishes to make decisions.

The evidence review and co-creation workshops with experts also highlighted the range of FBO staff behaviours and processes which FBOs may put in place to satisfy FHS consumer needs. These included:

-

To ensure safety, providing written allergen information to indicate the presence (or absence) of allergens, requiring staff to ask consumers to disclose if they have an FHS, and putting in processes to ensure clear and effective communication of consumer allergen requirements between staff[15]

-

To ensure confidence, talking with FHS consumers to understand FHS/condition and identify alternatives, repeating orders back to customer, and using visual prompts on dishes to show that the food is suitable for FHS requirements[16]

-

To ensure a normal dining experience, asking each and every customer if they have an FHS[17]

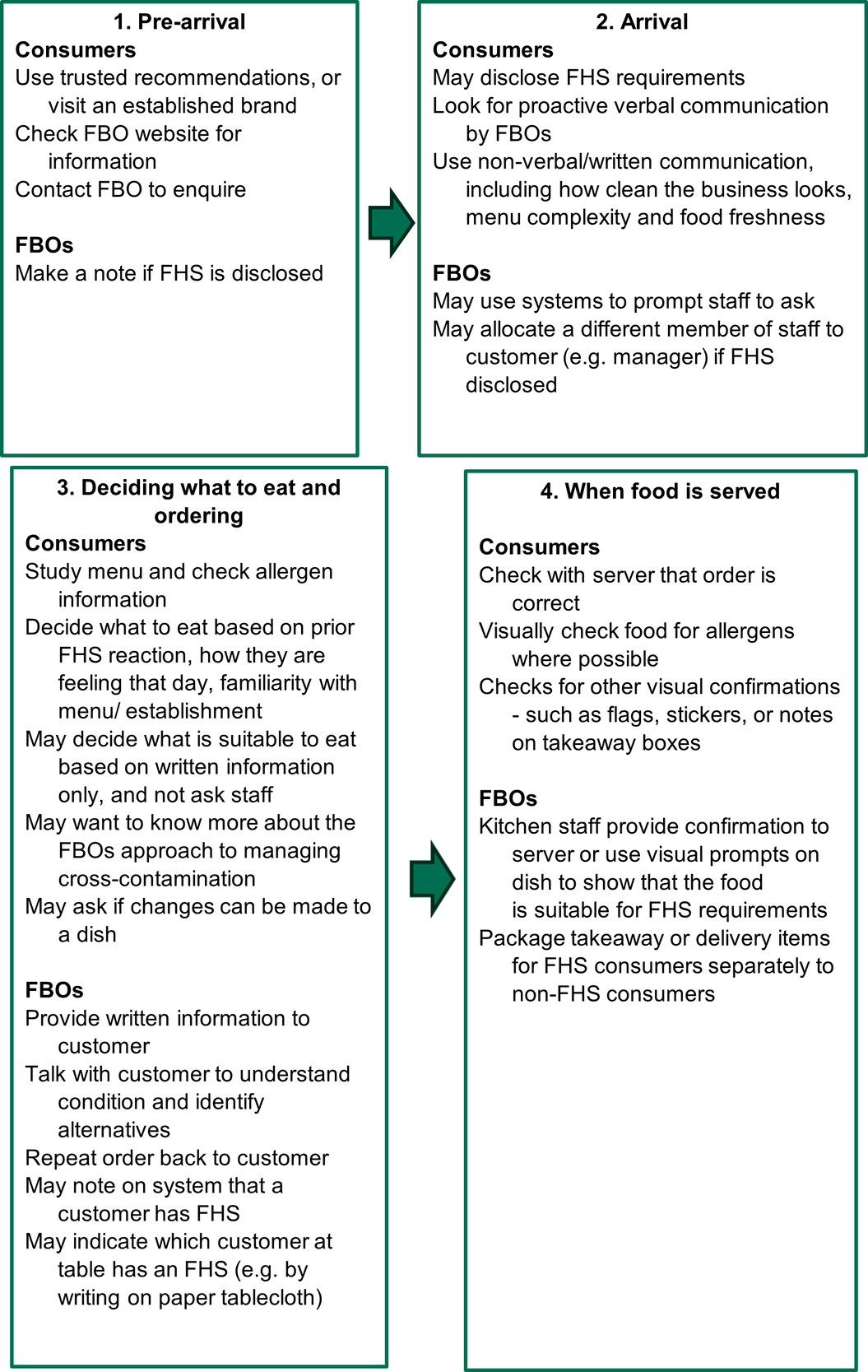

Figure 3 provides an illustration of the behaviours which FHS consumers and FBOs may perform to satisfy key needs. It is based on an unpublished template customer journey model provided by the FSA, which was built on using insights from previous research and from the co-creation workshops with experts and FHS consumers. The full customer journey map is in Appendix B.

Insights into the effectiveness of current communication methods

A variety of factors may limit the effectiveness of communication methods that are used to meet consumer needs. These factors have been identified through a combination of findings from primary research as part of this study, previous research focused on FHS consumers, and wider literature and theory related to effective communications.

FHS consumers may lack motivation to disclose their FHS

Both this study and previous research into FHS consumer behaviour note that low motivation can act as a barrier to FHS consumers disclosing their FHS to FBOs – despite FBOs seeing disclosure as key for ensuring consumer safety. If there are motivational barriers to performing a behaviour then this reduces the likelihood that behaviour occurs.[18]

Reasons for low motivation to disclose vary, but there are two key themes – a consumer’s appraisal of the risk in the situation and beliefs about consequences of disclosing.

Risk appraisal: A FHS consumer is more likely to disclose if they think there is a relevant risk and that disclosure will help them cope with this risk.[19] Some FHS consumers taking part in this study indicated they believe they have the necessary information to make a judgement on whether there is a risk through written allergen information only and / or their own judgement about how likely an allergen is to be present in a dish. They therefore believe that they can be safe without needing to disclose. However, as previous research has shown, consumers may lack awareness that there is a risk of inaccurate allergen information on menus[20] and may also lack knowledge of the additional actions required by FBOs to make a meal safe[21], potentially resulting in over confidence and an inaccurate judgement about risk.

Beliefs about consequences: FHS consumers may also sometimes feel that disclosure won’t protect them from the risk as it should do. For example, if staff appear not to be knowledgeable this can put people off disclosing[22], presumably because they are not confident in the food businesses’ ability to keep them safe (a key need). They therefore are not motivated to disclose. Other perceived consequences which may reduce FHS consumers’ motivation to disclose include: that staff will respond in a way that means they won’t be able to have a normal dining experience (a key need), that they will provide an unhelpful or unconstructive response[23], that they will react in ways that cause the consumer embarrassment[24] and may restrict the consumers’ choices about what they can eat[25]. There is also a concern that other people the consumer is eating with will perceive them as a nuisance[26].

In response to these motivational barriers, previous research has examined the effects of different types of motivational messages on FHS consumers’ intentions to disclose their FHS. For example, gain-framed messages that emphasise benefits or desirable outcomes have been found to be more effective for increasing behavioural intentions than loss-framed messages, that emphasise negative consequences of not adopting a behaviour [27]. This suggests that messaging which highlights a good eating out experience, rather than the avoidance of a food safety risk, are better suited to increasing motivation.

FHS consumers may not pay attention to allergen communications

Human perception is selective[28]. Cognitive economy refers to the tendency for cognitive processes to minimise processing effort and resources.[29] Due to limited processing capacity, people attend to some stimuli in the environment and ignore others. This can result in salience bias, which refers to people’s tendency to focus on items or information that are more noteworthy while ignoring others[30].

These biases were observed during in-situ testing of materials. For example, very few of the FHS consumers who took part in the in-situ tests noticed the sign encouraging disclosure until it was pointed out by the researcher after their food had been ordered. Researchers even observed instances of participants not noticing the sign even when looking directly at it.

Selective attention and salience bias means communications need to be designed and deployed in ways that increase the chances of catching the attention of target audiences. Luminance, texture, contrast, and scale can be used to help communications stand out and be noticed[31]. Timing and context also matter – people become habituated to noticing certain stimuli only at specific points[32]. Finally, personalisation can help make communications stand out, for example by explicitly addressing or representing the target audience (or their interests) in communications[33].

Behaviour change frameworks emphasise the importance of these elements for effective communications. For example, the EAST framework states that, for behaviour change to occur, behaviours need to be[34]: Easy, Attractive, Social and Timely. Applied to communications, this framework highlights the importance of making communications stand out (Attractive) and available at the point of need (Timely) to be effective in driving desired behaviours.

FHS consumers may misunderstand allergen communications

Previous research into FHS consumers’ views towards allergen information on menus highlights a need for allergen information to be simple and easy to read[35]. Features of menus which may affect this include:

-

How much information is provided on a menu – a lot of information can make a menu busy and more complex, and therefore more difficult to process[36].

-

Use of letter abbreviations and symbols – while some studies suggest consumers may find these easier to process[37], there have been food safety incidents arising from consumers misreading or misunderstanding the written information or symbols on a label or menu[38]

-

Use of colour - colours often carry pre-existing associations (e.g. red is unsafe, green is safe) which may affect how written communication is interpreted[39]. Coloured backgrounds may also affect how easy written information is to see and read[40].

Previous research[41] and the co-creation workshops in this research also suggest FHS consumers feel that a lack of consistency in allergen information communication across FBOs is a significant problem. A more standardised system may help avoid consumers having to learn the individual approach of each establishment[42].

As with selective attention and salience bias, these findings reflect the fact that people minimise the time they spend processing information. Consequently, information that is clear, simple and easy to process is more likely to be effective in achieving its communication objectives.

FBO allergen management and communication practices may not address consumer needs

FBO culture and practice can undermine the extent to which FHS consumer needs are met. Previous research has shown:

-

FBO staff may lack knowledge about allergens in general, and/or may lack knowledge about what allergens are present in the food being served[43]

-

FBO staff may forget to ask customers if they have an FHS[44]

-

FBO staff may lack sufficient language and communication skills to relay information accurately and appropriately to FHS consumers[45]

-

Information from suppliers may be absent or not detailed enough for FBOs to ensure information accuracy, plus insecure supply chains may result in last minute changes[46]

-

Updating written allergen information may carry costs for FBOs (such as money and time), meaning they are unable and/or unwilling to do this as regularly as needed[47]

-

It may be impractical to include all allergen information on a menu or a label[48].

-

FBO staff may have a variety of (misinformed) beliefs about allergens (for example, that FHS is a dietary choice), or assume that FHS consumers will always disclose if they are at risk[49]

A key implication of this is that signs, menus, labels and matrices are not a silver bullet for meeting FHS consumer needs. Rather, these communications materials should be understood as part of a wider system, all parts of which need to function effectively to meet FHS consumer needs. This system includes the need for:

-

FBO staff to have the capability (skills and knowledge) and opportunity (time) to effectively communicate with FHS customers, and to be motivated by beliefs to take FHS seriously and knowledge about the allergens present in a dish

-

FBOs to put in place processes and systems for allergen management and communication

-

FBOs to provide additional information on allergen management practices to consumers, for example a website

Principles for written communications

The findings above were used to inform and develop principles for effective written allergen communication. These are summarised below and discussed in more detail in Chapter 7.

These principles formed the basis for developing a variety of prototype executions of signs, menus, labels and matrices. These prototypes were initially tested and refined through the second round of co-creation workshops, after which a final set of prototypes were tested in digital and in-situ testing. The outcomes of these tests are discussed in the next chapter (Chapter 6).

It should be noted that while certain principles are common across all FBO allergen communication, others are particular to a sign or menu. Moreover, how each principle works in practice is context specific. Consequently, principles are grouped into the following categories:

-

written communications to encourage consumers to disclose if they have an FHS on a sign, menu or label (Table 9)

-

written communications indicating the presence of an allergen in a dish or product on a menu, label, or matrix (Table 10)

It should also be noted that these principles were informed primarily by consideration of consumers’ needs. Some (for example, the principle of consistency) may warrant further research with FBOs to understand their feasibility – particularly given the FBO need for flexibility in how they apply principles in the context of their establishment.

Principles described by FHS consumers in this research as the most important for the prototype usability and engagement are shown in emboldened text. This bolding is based on feedback in co-creation workshops and user testing.

6. Findings from user testing of communication materials

A sign prompting consumers to disclose if they have a FHS

Signs tested

Three signs (A-C) were tested during the online and in-situ consumer research (see Figure 4). The prototype designs all contained the same core message: “Please talk to us if you have a food allergy, intolerance or coeliac disease. We want to cater safely for everyone.” The designs varied in the use of:

-

Design of text – for example, font size and use of bolding to emphasise different aspects of the message.

-

Formatting – for example, using bullet points and spacing to change the layout of the message.

-

Logo - whether a logo was present or not, and if so, whether the FSA or FBO’s logo was used.

-

Messages – Sign B included an additional line stating “Our menu descriptions do not contain all ingredients and we may sometimes have to substitute ingredients.” This specific message was based on previous research showing a lack of consumer knowledge about substitutions and menu accuracy[50]. It was intended to motivate disclosure by highlighting the risk of relying on written information which may not be up to date.

The decision to test these particular signs was based on consumer and expert feedback from the co-creation workshops. During the workshops, FHS consumers and experts said signs need to be clear and simple and should communicate that FBOs care about the safety of their consumers. Signs also need to stand out and be accessible to readers with different needs. Specific considerations that emerged from this stage included that:

The sign should:

-

Provide a clear and simple call to action so consumers know what the FBO is asking from them.

-

Show empathy for consumers with FHS is valued. However, what matters most is consumers having confidence that they will be able to have a safe dining experience.

-

Use friendly language to encourage consumers to feel comfortable disclosing their FHS.

-

Mention coeliac disease in addition allergies and intolerances, due to it being a different condition (an autoimmune condition).

It should not:

-

Use colour at the expense of the legibility of the sign (e.g. due to coloured backgrounds reducing the contrast between the message and the background). Though colour on signs can be useful for grabbing attention and cueing certain associations (e.g. red = danger).

-

Use graphic elements which distract from the message, for example icons to signify the need for a consumer to talk (a megaphone) or to show a business caring (a heart).

-

Use humour and catchphrases as it can obscure meaning and create confusion.

The nine early prototypes that were developed and tested during the second round of co-creation workshops are shown in Figure 5. The sign with the white background and the FSA logo in the corner with the message: ‘We want to cater safely for everyone. Please let us know if you have a food allergy or intolerance’ (top right in Figure 5) emerged as a strong favourite across groups, as it met many of the considerations described above. This sign formed the basis of the prototypes taken through to user-testing.

User testing findings

Signs rarely led to FHS consumers disclosing their FHS, however, in follow-up interviews FHS consumers said they consider them important.

In-situ tests generated mixed evidence around the influence of signs on likelihood to disclose. There was an equal split of participants who disclosed their FHS to FBO staff, versus those who did not. Among participants who did disclose, almost all did so without noticing the sign. Most of these said they always disclose as a matter of routine; some did so in response to the server asking.

“They don’t usually ask because there’s not many people who have allergies. So, I just bring it to their attention.”

In-situ participant, restaurant

“A lot of places do fish and seafood, so I have to let them know [about my food hypersensitivity], or in case they use sesame oil or peanut oil… So yes, I have to disclose it all the time.”

In-situ participant, restaurant

Despite these findings, FHS consumers widely considered signs to be important for ensuring the safety of (other) FHS consumers, and for building confidence in FBOs, for example because they demonstrate that FBOs have considered FHS consumer needs.

Signs were often not noticed. Consumers recommended better placement and the use of colourful logos to improve salience, though this may still not be enough to capture attention.

The most common explanation for why the sign did not influence disclosure was because very few of the FHS consumers who took part in the in-situ tests noticed the sign until it was pointed out by the researcher after their food had been ordered. This suggests the salience of signs could be improved. In-situ testing participants suggested salience could be improved by positioning signs in places where consumers are likely to look, such as on front-doors, on or near menus, and around customer interaction points, for example, payment points. It is worth noting that this still may not be effective; researchers observed instances of participants not noticing the sign even when looking directly at it.

Digital testing further suggested that placement considerations vary depending on the service context. Participants in these online tests said that, in restaurants, signs should be incorporated at the front of the venue (e.g. on door fronts) and potentially as a part of the table setting. For cafes, they recommended visible wall placement near the service counter and possibly multiple placements due to the fast-paced environment. For market stalls, participants recommended clear, visible signage on counters or attached to display cabinets.

Inclusion of a logo was also generally preferred by participants. One reason for this was because logos were viewed as making the sign more salient, as images and colour were more noticeable than plain text. The sign without a logo (Sign C) was perceived as the least salient because it was plain and visually unappealing.

Finally, the use of emboldened text and large font size was commonly preferred because it made key messages readable from a distance.

Messages highlighting risks of non-disclosure were perceived as more motivating.

Some consumers did not disclose as they were confident that they could make a safe meal choice without doing so. This replicates findings from previous research (see Chapter 5 for further discussion).

In terms of motivation, only Sign B, which sought to motivate by highlighting the risk of relying on written information only, appeared to influence confidence levels in a way that motivated disclosure. This sign was tested in the café and was not noticed by any participants during their purchase. However, during follow-up interviews, several participants remarked that the additional message increased their perceptions of risk and may have motivated them to disclose if they had seen it.

“This [bold message] is the friendly bit, but this [additional message] below is probably more important than that [bold message], because ‘What are you going to substitute?’ That’s very important to me. So, I would say it would all need to be in bold… because that’s [bold message] the invite and this [additional message] is the information.”

In-situ participant, café

Despite this finding, Sign B was also found to be too wordy by other FHS consumers and less effective at meeting the principle of being simple and getting to the point.

While logos increase consumer confidence that allergen management is taken seriously, use of the FSA logo signals (incorrectly) that an FBO has been accredited and can therefore be misleading.

FHS consumers believed signs which included a logo indicated that the FBO took allergen management more seriously than those without a logo.

Initially, FHS consumers preferred the sign with the FSA logo (Sign A) as it indicated the FBO was compliant with safe allergen management practices. Specifically, consumers were reassured that the FBO had been accredited by the FSA to cater for them safely.

“I like the fact that they’ve got Food Standards Agency’s logo on there… it shows that they do check their catering to clients, that they do it safely… I feel like it’s all been checked… It always helps when you have a good official body to keep everything in line.”

In-situ participant, restaurant

However, after the researcher explained that the use of such disclosure notices was unlikely to be related to any official checks, FHS consumers perceived the inclusion of the FSA logo was misleading, and so to be avoided.

In this context, FHS consumers next preferred the sign with the FBO logo (Sign B) as it indicated the FBO took ownership and responsibility for allergen management and customer safety.

FHS consumers least preferred sign was the one without a logo (Sign C), which was associated with an FBO doing the bare minimum to comply with regulations. In these cases, the sign did not improve (and possibly reduced) confidence among consumers that the FBO took allergen management seriously.

Simple messages, emboldened larger font and spacing of information makes messages easier to process

FHS consumers preferred signs that used simple language and that only communicated essential information. However, opinions varied over what constituted an appropriate amount of detail. For example, most FHS consumers saw Sign B (with the additional risk message about menu descriptions not including all ingredients and having to substitute ingredients sometimes) as being too wordy. However, some consumers thought this information essential for making a safe choice, and therefore appropriate to include.

Design and formatting also emerged as key considerations for improving the clarity and simplicity of the signs. FHS consumers preferred the use of emboldened text, large font size and spacing out information by using line breaks, because it made key messages easier to read. However, they saw the use of bullet points as over complicated and unnecessary.

Table 11 below provides a summary of views on signs from the online and in-situ FHS consumer testing.

FBO views on the signs

Owners of all three food businesses were interviewed about the signs. Test signs displayed in the food businesses for the fieldwork period were as follows:

-

Sign A was tested in a restaurant with table service. The restaurant does not currently use an allergen disclosure sign but has a notice to disclose on the menu.

-

Sign B was tested in a café with counter service (the FBO’s logo was used for this execution). The restaurant does not currently use an allergen disclosure sign but has a notice to disclose on the menu.

-

Sign C was tested in a market stall. The stall currently has a large (approx. 70 x 40 cm), handwritten allergen disclosure sign on blackboard using white marker and capitalised text. The current sign reads: ALLERGENS[51] OR INTOLERANCE. *PLEASE ASK A MEMBER OF THE STAFF FOR ALLERGEN INFORMATION*

Given the small sample size, broader implications cannot be drawn from the FBO interviews. Findings are not representative and used for illustrative purposes only.

Overall, FBO feedback on the sign fell into three areas: the need for a sign; placement of the sign; and views on the sign message.

FBOs expressed different views about the need for a sign.

Both the café and market stall owners believed that signs in general were reassuring and could encourage consumers to disclose any FHS needs. For the market stall especially, their current sign was the main way to communicate about allergens to customers. The café did not currently have a disclosure sign, as they felt the message was better placed on the menu as it was more likely to be seen at point of order. However, after testing sign B, the cafe owner felt the sign provided “peace of mind” for both customer and the business (to help protect them in case of a claim). The café owner asked to keep the sign for ongoing use. The restaurant owner was less convinced on the need to use a sign, as they asked customers to disclose their allergen needs at point of order.

FBOs had different views on where it would be best to place a sign, linked to their service model and aesthetic considerations.

The restaurant owner had concerns about where to place the sign. The restaurant had artwork and pictures on the wall, and the sign was not noticed during fieldwork. The restaurant owner believed a sign would need to be large and visually obvious to stand out, which would not fit well with the look and feel of the restaurant. Moreover, the restaurant owner also believed that customers were more likely to take notice of a message to disclose on a menu than a sign on a wall, as service was at the table.

The cafe and market stall owners had fewer concerns about sign placement – mainly as customers for both businesses would order food in one place (at the counter or the stall front). This meant owners perceived it as relatively easy to place a sign nearby so that it would be noticed, the assumption being that a sign placed near the food ordering location would be more noticeable. Note that observations during the in-situ tests found this assumption to be incorrect in most cases.

FBOs did not have strong views towards the content of messages, however, the need for signs to be visually appealing was noted.

The restaurant and café owners did not have any preferences or particular views about the message on their test sign, or those of the other prototypes – feeling they were all fairly similar. The market stall owner, who tested a sign with a bullet point style, said the message felt ‘a bit academic’ and the overall execution was less “eye-catching” compared to their chalkboard signs which “fitted the aesthetic”. The market stall owner did not believe the sign made any difference to how her customers shopped.

FBOs did not have strong views towards the need for and choice of logo.

There were mixed views on the need for a logo on the sign, though no FBO was opposed to this. Overall, there was a slight preference for the FBO logo to appear on the sign, rather than the FSA logo, as it made the message feel that it was from the business.

Allergen information communication for written materials to indicate presence of allergens

Menus

Menus tested

Four menu prototype designs (A-D) were tested during the digital consumer research (see Figure 6). Menus based on these designs were also tested in-situ in two food business settings. Specifically, the FBOs current menu was redesigned in the style of the following prototypes:

-

For a restaurant with table service, their existing menu was redesigned with icons to indicate the presence of allergens in a dish. This was done in the style of prototype Menu D.

- The corresponding emboldened text menu (Menu C) was also comparatively tested during the interview.

-

For a café with counter service, their existing menu was redesigned with emboldened text to indicate the presence of allergens in a dish. This was done in the style of prototype Menu B.

- The corresponding icon menu (Menu A) was also comparatively tested during the interview.

The prototype designs were used to test the following variables:

-

Circular icons vs. emboldened text

-

Placement of disclosure messages (top vs. bottom)

-

Background of disclosure message (colour vs. no colour)

-

Content of disclosure message – the main disclosure message ‘Please talk to us if you have a food allergy, intolerance or coeliac disease so that we can cater safely for you’ was on each menu. The additional risk message was varied to either highlight cross-contamination risks (something which FHS consumers are more likely to be already aware of as a risk) or to highlight that written information on menus may be incomplete (as not all ingredients are listed) or inaccurate (due to ingredient substitutions) – something which FHS consumers may be less cognisant of.

Table 12 summarises the differences in how allergen information was displayed for the menu prototype designs.

Co-creation workshop insights informing menu prototypes

The design of the prototype menus was based on feedback from the co-creation workshops. During these workshops, FHS consumers and experts said that menus which utilised colourful icons or emboldened text were easiest to understand and supported customers to identify menu options which were most suitable for them. Specifically:

-

icons could help FHS consumers choose between dishes more quickly.

-

the use of colour helped to draw attention to the icons.

-

emboldened text was the simplest way to indicate presence of an allergen in a dish.

Whilst participants said they were not currently familiar with a system of allergen icons; it was mentioned that (if a consistent system was implemented) over time they would learn which icons were relevant to them, making them easier to use.

Additionally, during the ideation stage, 3 different icon executions were discussed and compared prior to the protypes being finalised for testing. These are shown in Figure 7.

When reviewing these prototype menu executions, FHS consumers and experts said that:

-

using letter abbreviations for the 14 allergens was cognitively hard to process, and cued associations with chemicals and the periodic table.

-

using a strikethrough on an icon to indicate the absence of an allergen in a dish was not intuitive,[52] and led to menus being visually complex and hard to navigate

-

circular shaped icons were more familiar than squares, and consequently easier to use.

Consequently, circular shaped icons were selected to use in testing stage, with the following minor revisions based on consumer and expert feedback:

-

each allergen should have a separate colour.

-

icons should be bolder, with greater use of colour to help them stand out.

-

the sulphur dioxide, celery, egg and milk icons should be changed to more clearly reflect the allergen of interest.

User testing findings

How consumers used menus

FHS consumers used menus in a variety of different ways, and context was especially important in the in-situ testing stage

FHS consumers said their familiarity with the cuisine, the ‘look and feel’ of the restaurant (including how busy and professional it looked), how hungry they felt, their mood and what they fancied eating, together with the time they had to peruse the menu,[53] all influenced how a menu was read and how allergen information was used.

Typically, FHS consumers scanned a menu from top to bottom and left to right. They began their search by looking at different categories of food (for example, pasta or salad), to make a choice about what they broadly wished to eat. This was done without a focus on any allergens present in the dishes. Once a category had been decided, a more detailed review of individual dishes was undertaken.

For emboldened text menu executions, the detailed review was done a dish at a time, with the allergen information for each dish read in turn. For icon menu executions, most consumers used icons to identify dishes they could not eat and focused on those where the icon was absent. Other shortcuts were sometimes used to identify suitable dishes to eat, for example those labelled vegan in the context of someone with a milk intolerance.

Disclosure messages on menus

Placing disclosure messages on menus, at the top of menus, and within a coloured box can increase salience

As shown above in Table 12, each menu in the testing stage had an allergen disclosure message. The position and content of the message varied across the menus. Menu B also used a coloured box at the bottom of the menu to draw attention to the message.

Overall, from the in-situ testing, disclosure messages were more likely to be noticed:

-

on a menu rather than on a sign.

-

when the message was at the top of the menu rather than the bottom.

-

when the message was placed in a coloured box rather than just as text.

Overall, FHS consumers said that putting an allergen disclosure message on a menu was more likely to be noticed than on a sign, as their attention is focused on the menu at point of choosing food.

“I feel like it’s better to have it [the message] on the menu rather than on the wall somewhere, because that’s where people are going to look. I feel like the top things people are going to do is check the menu and speak to the staff.”

In-situ participant, restaurant

Additionally, as information is generally read from top to bottom and left to right, the allergen disclosure message on Menu D - which was in the bottom right-hand corner - was least noticeable (and was not noticed by several consumers in the restaurant during the in-situ test).

Disclosure message content generated mixed responses and some consumers wanted the call to action to be foregrounded more clearly

As noted in Table 12, each menu included one of two different disclosure messages:

-

Message 1: Our food is prepared in a kitchen where allergens are present. Please talk to us if you have a food allergy, intolerance or coeliac disease so that we can cater safely for you.

-

Message 2: Our menu descriptions do not contain all ingredients and we may sometimes need to substitute ingredients. Please talk to us if you have a food allergy, intolerance or coeliac disease so that we can cater safely for you.[54]

FHS consumers saw both messages as reassuring and clear, though both were seen as wordy, and some consumers questioned whether the reason for disclosure was really needed. In this context, generally consumers preferred the ‘please talk to us’ part of the message to be emboldened and placed before the reason why – a finding which reflects the importance of communicating a clear and simple action that is easy to do[55]. No differences were found in consumers reactions to the content of the messages.

Written allergen information on menus

Emboldened text executions were overall perceived as easier to use than icons, however both worked in practice.

FHS consumers in the online testing said emboldened text executions were easier to read than icons. This is because the emboldened text executions were visually clearer, unambiguous and did not require the use of a legend to identify the allergen of interest. When discussing the icon menus, FHS consumers found Menu D most difficult to use, due to the placement of the icon legend being adjacent to the disclosure message at the bottom of menu. They said having such a large amount of detailed information in a small area of the menu made it harder to use.

In the in-situ testing, where people were actually using the menus, opinions were more mixed. Overall, both icon and emboldened text executions were seen as good approaches by participants. Emboldened text executions were easier to read (icons required more cognitive work to interpret), however icons were seen as having the advantage of enabling them to quickly scan the menu and find a dish that was safe to eat. This view was also expressed by some consumers in the digital testing.

“Well, [emboldened text] it’s easier on the eye, in the sense that it is not a lot of brainwork… It’s all in one page, and I don’t have to go to the bottom to work out what’s in the dish… It’s not as pretty looking as the icons, however it’s more straight to the point… You don’t want to be sitting here trying to work out what each thing means”.

FHS consumer, in-situ test, restaurant

“I think icons are easier to recognise… You still have people who can’t read properly, whereas they will recognise icons.”

FHS consumer, in-situ test, market stall

Coloured icons perceived as providing additional benefits for ease of use. Improved colour coding and consumer familiarity may also increase their utility.

Consumers in the digital testing raised concerns over whether certain colours for the icons were too alike and whether the colour was intuitively related to each allergen. For example, as illustrated in Figure 8, consumers said the red and pink colours for crustaceans and molluscs were very similar, and alike to mustard. Additionally, pink and dark orange colours were not associated with molluscs or mustard respectively[56].

“People’s eyes may be drawn to a colour more so, than black and white… Although they don’t really relate- milk being blue, I think it’s more eye catching.”

FHS consumer, in-situ test, café

Consumers in the co-creation workshops noted that barriers to processing icons might reduce over time as they became more familiar with their icon. However, this was not raised by participants in the user tests.

Table 13, below, provides an overview of what FHS consumers in the in-situ and online testing thought worked well and less well for menus that used icons versus emboldened text.