1.0. Executive summary

The Requirements for School Food Regulations 2014 in England (known as the ‘School Food Standards’) define the foods and drinks that must be provided, those which are restricted, and those that must not be provided in schools.

The Department for Education and the Food Standards Agency recognise that schools, trusts, local authorities and caterers are working extremely hard to deliver school food, often in challenging circumstances. The Department for Education’s published guidance for schools, trustees and governors on the School Food Standards emphasises the importance of leadership in creating a culture and ethos of healthy eating, whilst also making clear that not all actions are a head teacher’s responsibility and that these can be shared across a school with some actions best taken by cooks, external caterers, other school management staff or volunteers. The day-to-day effort already made by leaders and staff in delivering food for pupils requires important recognition. The pilot’s intention is to find ways to support improvements where needed.

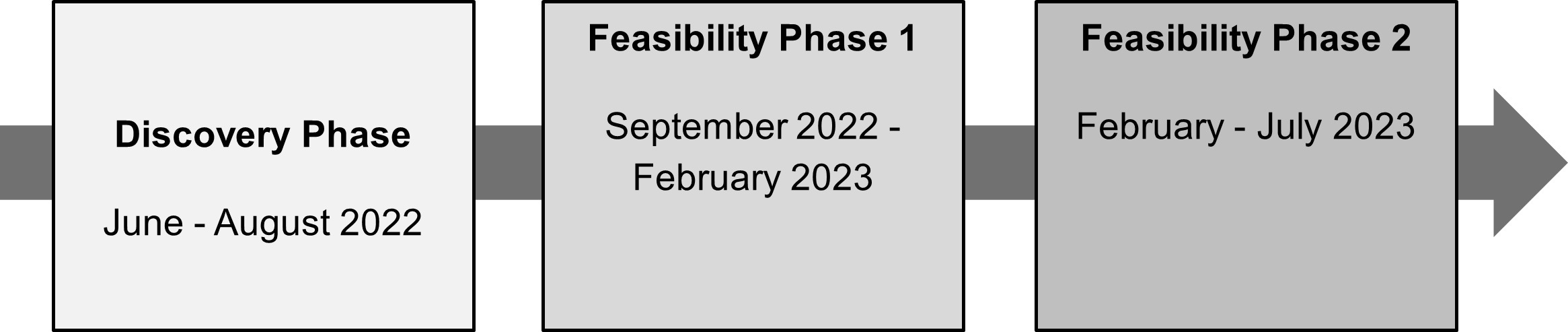

The Department for Education and the Foods Standards Agency, with support from the Office of Health Improvement and Disparities, developed the School Food Standards Compliance Pilot as a novel approach to assuring the School Food Standards. Its purpose was to test if Food Safety Officers could carry out a School Food Standards check (referred to as the ‘check’) to identify potential non-compliance with the School Food Standards alongside food hygiene inspections. Food Safety Officers are trained professionals and are responsible for inspecting a range of business types at different points on behalf of their local authority. In addition, where potential non-compliance with the School Food Standards was identified, the pilot explored whether appropriate teams within local authorities would be able to support schools. The pilot launched in September 2022 across 18 local authorities that volunteered to participate and has included 3 phases: Discovery, Feasibility Phase 1 and Feasibility Phase 2. The reports on the findings of the Discovery Phase and Feasibility Phase 1 were published in November 2023.

This report sets out the findings of research that explored the responses of local authorities and schools to the checks, within the final phase (Phase 2) of the pilot. For local authorities, the focus was on how they perceived and responded to the check data provided by Food Safety Officers carrying out the checks. For schools, the focus was on examining their experiences of the checks and understanding the actions and behaviour change they had undertaken to address potential non-compliance.

Methodology

This report brings together data from four different sources including:

-

A survey completed by a sample of 18 Food Safety Officers who had conducted checks in Phase 2.

-

A survey completed by a sample of 63 schools who had received a check during the pilot.

-

In-depth interviews completed with 27 local authority staff in November and December 2023.

-

In-depth interviews completed with 7 school staff and 6 catering staff completed in June and July 2023.

An important caveat to these findings is that the participating local authorities are unlikely to be representative as they opted into the pilot voluntarily, and so may have had more resource, expertise, and engagement with school food in comparison to other local authorities in England.

Results

Food Safety Officers reported that the checks were straightforward to administer, and that the changes made to the question sets, guidance and reporting process in the final phase of the pilot helped make the process easier and more efficient. While it is likely that the checks were being applied consistently by Food Safety Officers within a local authority, it is possible that there were inconsistencies in application between local authorities such as how Food Safety Officers defined ‘meat products’. Many local authority participants also felt that changes made to question sets due to findings from Phase 1 of the research, as well as the new requirement to rotate them, reduced the quality of the data, as less data was being provided and compliance could not be compared reliably across schools. Schools reported that they were happy to facilitate the checks, and in some cases this acted as a catalyst for them to review their school food provision; however, overall there was inconsistency in the extent to which they acted to address reported instances of potential non-compliance.

In testing the feasibility of an effective response to the checks, significant barriers were experienced by local authorities regarding effectively following up with schools where potential non-compliance was marked by the checks. There were some examples cited by schools and local authorities where this process worked successfully, typically when school staff were supportive and engaged or local authorities had the capacity and capability to provide substantial support (often achieved through having a dedicated team that specialised in school food). However, in many local authorities there were issues regarding communicating both internally and when engaging with schools and caterers. Some local authorities also did not have the resource or expertise to provide support for schools at all.

Recommendations

There are ways in which the check could be improved, by resolving remaining areas of uncertainty in the questions and ensuring that communication about the check and its results reach catering managers and external catering suppliers. There may be an opportunity to target the check to a greater extent to more efficiently capture instances of potential non-compliance. This targeting could focus on certain types of school being more likely to receive a check (for example, targeting secondary schools, where multiple instances of potential non-compliance were more common), and/or the specific questions asked at each school.

Achieving a consistently effective response to the checks requires overcoming the barriers identified. Given structures and relationships between teams in the local authorities were found to vary, it will be challenging to identify a nationally standardised follow-up process that could be put into practice across all local authorities. Any standardised follow-up process should aim to target the same outcome(s), such as raised awareness of the School Food Standards legal obligations amongst governors and trustees, but not prescribe a means of doing this. This will help ensure all local authorities would be able to follow this guidance regardless of their specific local structures and models for operating in relation to school food. Given that resource and expertise also varied, additional support may be needed so that all local authorities can fulfil their role in a standardised follow-up process effectively.

2.0. Introduction

In England, the School Food Standards were introduced to help children develop healthy eating habits and ensure that they have the energy and nutrition they need to get the most from their whole school day. The Requirements for School Food Regulations 2014 define the foods and drinks that must be provided, those which are restricted, and those that must not be provided. They regulate the food and drink provided at both lunchtime and at other times of the school day, including, breakfast clubs, tuck shops, mid-morning break, vending and after school clubs. The School Food Standards are mandatory for all maintained schools, academies and free schools with school governing boards responsible for ensuring the standards are met.

Currently there is little available published evidence on the extent to which schools comply with the School Food Standards or how they are generally implemented. In February 2022 the UK Government published the White Paper, ‘Levelling Up the United Kingdom’, which stated that the Department for Education and the Food Standards Agency would jointly develop a new approach to assessing and supporting compliance with the School Food Standards.

To deliver this commitment, the Department for Education and the Food Standards Agency developed the School Food Standards Compliance Pilot. The purpose of this pilot was:

-

To test if Food Safety Officers carrying out food hygiene inspections could ask questions and make observations of food preparation or service areas to identify instances of potential non-compliance with the School Food Standards. This is referred to as the ‘School Food Standards check’; and

-

Where instances of potential non-compliance with the School Food Standards were identified, appropriate teams within local authorities were able to provide support to schools to make improvements.

It is worth noting that the pilot did not require Food Safety Officers to check if all food provision on site was compliant with the School Food Standards. Instead, the check was completed on food provision provided by the food business operator undergoing the food hygiene inspection (i.e. the catering company at the school). This typically covered school lunch, and sometimes additionally or alternatively covered food other than lunch, such as breakfast and after school clubs. Schools can have multiple food business operators, with separate operators providing lunch and breakfast provision for example.

The School Food Standards Compliance Pilot (herein referred to as the ‘pilot’) was initially launched in September 2022 among 18 local authorities who volunteered to take part (Appendix A: List of local authorities taking part in the pilot). Of these 18 local authorities, two are county councils (the upper-tier local authority). County councils do not undertake food hygiene inspections, as these take place at the district council level (the lower-tier local authority) in two-tier areas. The School Food Standards check therefore took place in 16 local authorities.

Two county councils volunteered to take part in the pilot, given their role in responding to the outcomes of the check for districts within their authority where these took place.

The pilot was developed across several phases (Figure 1):

-

The ‘Discovery Phase’, followed by

-

‘Feasibility Phase 1’, and

-

The final phase, ‘Feasibility Phase 2’.

Previous Pilot Phases

The aim of the Discovery Phase (June – August 2022) was to inform the launch of the pilot in September 2022 by:

-

Investigating current food procurement and provision practices across local authorities;

-

Assessing the feasibility of Food Safety Officers completing the School Food Standards checks alongside the regular food hygiene inspections;

-

Developing questions that Food Safety Officers could use to undertake the check; and,

-

Understanding the potential ways in which local authorities might follow up on checks to help support schools to comply with the School Food Standards.

The aims of the Feasibility Phase 1 (September 2022 – February 2023) were:

-

To test the pilot’s design in the field.

-

To explore the feasibility of Food Safety Officers undertaking checks of school food against the School Food Standards. This was to identify issues with a longlist of specific questions and to assess training and guidance provided for Food Safety Officers.

-

To understand the experiences of Food Safety Officers completing the School Food Standards check.

-

To understand local authorities’ experience of responding to the results of the check.

Evidence from the Feasibility Phase 1 was used to inform and update the design of the final phase of the pilot, Feasibility Phase 2.

The aim of this research report is to present the findings of research that was conducted on this final phase, Feasibility Phase 2 (February 2023 to July 2023). The objectives of this research were:

-

To understand how schools and caterers experienced the checks, and any improvements that could be made from their perspectives.

-

To examine and illustrate the actions and behaviour change schools and caterers have undertaken to address potential non-compliance with the School Food Standards, and the ways in which the check and any local authority interventions affected these.

-

To explore the impact the checks had on Food Safety Officers and their food hygiene inspections.

-

To explore local authority teams’ perceptions of the data from the checks and how these affected their responses.

-

To understand how local authority teams have responded to the data and information provided by Food Safety Officers who carried out the checks.

-

To examine how, if at all, local authority teams’ responses to the data differ compared with their responses at Phase 1 and why.

2.1. Phase 2 pilot approach

Evidence collected from the Feasibility Phase 1 was used to develop the pilot approach for the Feasibility Phase 2. The project team at the Department for Education and Food Standards Agency reflected on the findings from Phase 1 of the pilot and implemented changes for Phase 2. These changes were:

-

Rotating question sets: The Phase 1 research suggested that some Food Safety Officers felt that 6 questions took too long to complete, possibly straining their capacity during a regular hygiene inspection. In Phase 2, rather than being allocated 6 questions to check using one of two question groups (A or B to check at each school visited), Food Safety Officers were asked to check for potential non-compliance at each school for 3 or 4 questions using one of three question sets (A, B or C). They were asked to rotate which set they checked at each school they visited. The standard “Is free fresh drinking water available at all times?” was not included in Phase 2 checks due to universal compliance within Phase 1 when checked. The content of the 3 question sets can be found in Appendix E: Phase 2 check questions.

-

Updates to the aide memoire and online form: Feasibility Phase 1 results suggested that there was uncertainty around specific check questions and that Food Safety Officers wanted more guidance. As a result, for Phase 2 the information within the aide memoire, which supported Food Safety Officers to complete their checks and determine potential non-compliance with each standard, was updated. Food Safety Officers were also able to now complete the online form at the point of the visit, with a portable document file of the outcomes and their notes automatically generated. This was in response to the Phase 1 research, suggesting some duplication between filling in an aide memoire at the visit and latterly filling in an online form. See Appendix B: Phase 2 Aide Memoires for a copy of the three Phase 2 aide memoires.

Aside from these changes, the approach was the same as that outlined in the Feasibility Phase 1 report. The 6 steps that Food Safety Officers were advised to complete for each check can be found in Appendix F: FSO steps to administer the check.

3.0. Methodology

Feasibility Phase 2 involved two strands of research. The first strand involved the school survey and depth interviews with schools and caterers, and took place between June and July 2023. The second strand involved the Food Safety Officer survey and depth interviews with local authority staff, and took place between November and December 2023.

3.1. Research objectives

Schools and Caterers

-

To understand how schools and caterers experienced the checks, and any improvements that could be made from their perspectives.

-

To examine and illustrate the actions and behaviour change schools and caterers have undertaken to address potential non-compliance with the School Food Standards, and the ways in which the check and any local authority interventions affected these.

Local Authorities and Food Safety Officers

-

To explore the impact the checks had on Food Safety Officers and their food hygiene inspections.

-

To explore local authority teams’ perceptions of the data from the checks and how these affected their responses.

-

To understand how local authority teams have responded to the data and information provided by Food Safety Officers who carried out the checks.

-

To examine how, if at all, local authority teams’ responses to the data differ compared with their responses at Phase 1 and why.

3.2. Approach

This report brings together data from four different sources:

-

A survey with Food Safety Officers,

-

A survey with schools,

-

In-depth interviews with schools and caterers, and

-

In-depth interviews with different teams within local authorities, including:

-

Environmental Health (which included Food Safety Officers)

-

Public Health, and

-

Specialised school food teams.

-

Taking this approach means the different relative strengths of each type of data source can be drawn on, to support the interpretation of findings and triangulate the data. While the survey data allowed for the quantification of experiences across the sample in different local authorities, the qualitative research provided a rich understanding of individual experiences and situations that helped to explain and understand the patterns observed in the quantitative research.

Due to the difference in research methods, the findings are reported differently. Findings from the qualitative research are described and illustrated by quotations from individual participants. Qualitative data is by its nature non-numerical as it aims to illustrate the range of current opinion rather than quantity, which is important to keep in mind when interpreting these results. However, within the results section certain phrases are used to give an indication of how often a particular finding or theme was raised, to highlight the commonalities and differences encountered in participants’ responses. For example, the phrases ‘some’, ‘a few’ or ‘several’ are used to indicate when a certain theme was raised by more than one participant but less than half of the total sample. If themes were raised by the majority of participants but not all of them, the phrase ‘most’ is used.

The survey data is quantified numerically and presented in the format of n out of N participants, where N is the number of participants that answered that specific survey question (which can vary from the total survey sample due to question routing or some individuals not answering that particular question).

Food Safety Officer and School Surveys

Food Safety Officer Survey

Food Safety Officers who had completed at least one check during Phase 2 of the pilot period were invited to complete a short online survey to understand their experiences of completing and reporting the results of the checks in Phase 2. The survey link was emailed directly to 44 Food Safety Officers working across the 16 pilot local authorities. The survey included questions about whether they had experienced any difficulties conducting the checks and how they felt about the changes made between Phases 1 and 2. The survey was completed by 18 respondents, 17 of whom had participated in Phase 1 of the pilot as well. According to the survey, the median number of checks completed in Phase 2 of the pilot was 10 checks while the mean was 18 checks, meaning some participating local authorities had completed many more checks than others. All survey responses were completed in August and September 2023, with findings used to inform the development of topic guides for the qualitative in-depth interviews. See Appendix D: FSO Survey Questionnaire for the full survey text.

School Survey

Additionally, an online survey (referred to in this report as the ‘school survey’) was sent in May 2023 to all 381 schools that had received a check across the pilot, up to this point. They were invited to answer questions about their awareness of the pilot prior to the check, their experience of the check itself and whether they received any follow-up from their local authority after the check. Analysis was based on the 63 participants who completed the survey. See Appendix C: School Survey Questionnaire for the full survey text.

Respondents held a range of different roles within their schools, which were:

-

9 administrators.

-

16 catering managers.

-

2 catering staff members.

-

15 head teachers and 1 deputy head teacher.

-

12 business managers.

-

4 operations managers.

-

4 other oversight roles.

14 out of the 16 pilot local authorities were represented in the survey. Most of the schools that had responded to the survey had been checked during Phase 1 of the pilot (51/63), rather than at Phase 2. Of these schools, 30 were academies, 26 were maintained, 2 were free schools and 4 were special schools (information was not available for one respondent). Most respondents were primary schools (44), although there was also 9 secondary schools and 3 all-through schools.

The number of responses for each question varied due to survey routing and some drop-offs. Therefore, when survey data is cited, it refers to the total number of respondents that answered the question.

In-depth interviews with schools and caterers

All schools and caterers who had a check over the pilot and had given consent to be recontacted were invited to participate in a 20 to 45 minute online or telephone in-depth interview to explore their experience of the check and whether they had made any changes to school food provision following it. These were conducted with staff working at 7 schools and 6 catering companies, covering 11 out of the 16 pilot local authorities. These took place in June and July 2023 and focused on schools’ and caterers’ responses to the checks.

In-depth interviews with local authorities

Local authorities were invited to reflect on their overall experiences of the pilot, focusing on how Phase 2 had differed from Phase 1. These participants were a mix of those who had taken part in the Feasibility Phase 1 research, contacts collected from Phase 1 participants, and those who had completed the Phase 2 Food Safety Officer survey and opted in to being invited for follow-up contact.

Overall, 27 participants were interviewed, covering a range of roles across 15 out of the 16 local authorities who were administering checks. This comprised:

-

7 Food Safety Officers who had completed a check in at least one school.

-

20 local authority staff members who were overseeing the receipt of check results and taking responsibility for the follow-up support provided to schools after the check.

Interviews lasted 45 minutes and took place in November and December 2023.

There was considerable variance in who participated in the in-depth interviews from different local authorities, in terms of their role, responsibilities, and involvement in the pilot. This was due to variations in different team sizes, organisational structures, and ways of working evident in the local authorities as found in the Discovery phase research.

The types of teams and roles included in these interviews were:

-

Environmental Health, including Food Safety Officers and team leads.

-

Public Health, including senior managers, specialists or consultants, and nutritionists.

-

Specialised school food teams, including catering services and school food staff.

3.3. Methodological considerations

An important caveat to these findings is that the participating local authorities, schools and private caterers are unlikely to be representative. These organisations opted into the pilot and research voluntarily and so probably had a higher level of engagement with school food than other similar organisations who did not choose to participate. Local authorities who self-selected may have had more resource and expertise in this area than others in England. An additional consideration to note is that the sample sizes were small across all parts of the research. The surveys of Food Safety Officers and schools both had a low response rate, and a small number of schools and caterers participated in the depth interviews.

4.0. Results and discussion

This chapter outlines findings from the research and is divided into three main sections outlined below.

Section 4.1: Focuses on the experience of the check from the perspective of Food Safety Officers administering the check and school staff receiving the findings of the check.

Section 4.2: Outlines the results of the check in terms of patterns observed across local authorities and how the data differed between Phase 1 and Phase 2 of the pilot.

Section 4.3: Focuses on the post-check follow-up process in terms of responses from local authorities and changes made by schools, and within this process the remaining barriers to addressing potential non-compliance.

4.1. Experience of the checks

Awareness of the check

Awareness of the School Food Standards check amongst school staff prior to the Food Safety Officer’s visit was low. In the school survey, around half of respondents (35/63) were not aware of the pilot at all prior to the check. Those who said they were already aware had generally heard about it through communications from the Department for Education or the Food Standards Agency (10/28), some through their local authority (7/28) and a minority from either external media, caterers, National Association of Head Teachers trade union or word of mouth. In qualitative interviews, Food Safety Officers also reported that schools’ awareness of the check prior to the visit was low – some school staff they interacted with had not read the letter sent out at the start of the pilot, and a few said they had not received it. However, despite this low initial awareness all schools were receptive and cooperative, and most school survey participants (51/63) were now aware that a check had taken place at their school. In the Food Safety Officer survey, no respondents reported that staff at schools raised any objections during the checks (0/18).

Catering managers were generally unaware the check could happen, which in a few cases affected their experience of the process and how efficiently it was conducted. This may have happened as catering staff were not passed on the email received by schools at the start of the pilot that informed them of the check. In a few cases, catering managers had been informed about the check, either by the headteacher or local authority. However, catering staff generally had low awareness of the check prior to it occurring, resulting in instances in which they were absent or busy when it took place.

As well as low awareness, there was also evidence of low understanding of the School Food Standards checks among some schools and caterers. Some were unclear that the check was separate from regular food hygiene inspection visits. Some noted that the check questions were mixed into the food hygiene inspection, or that they received one report covering feedback for both, making it more difficult to differentiate between the two processes. In a minority of cases, schools and catering staff mistakenly thought that the check was part of the star rating system used in food hygiene inspections and may have perceived that they had no instances of potential non-compliance due to having achieved a high star rating.

Administering the checks

Food Safety Officers generally took a consistent approach to the checks and found the process straightforward. They found the checks became easier and faster to complete over time, and just under half (8/18) felt confident after 2 to 3 checks. The majority (14/18) agreed they had a good enough understanding to carry out the checks. Similarities in approaches across Food Safety Officers included:

-

Arriving in the morning to see food preparation and talk to staff.

-

Checks taking around 15-30 minutes to complete (sometimes longer at secondary schools).

-

Leaving a copy of the report at schools.

During qualitative interviews, most Food Safety Officers did not report any major impact on food hygiene inspections, in part due to the changes to the question sets in Phase 2 shortening the duration of the check. However, some reported feeling the check still added pressure to timings, which in some cases may have affected the food hygiene inspection.

A few Food Safety Officers reported it having a more significant impact. One reported that they would previously conduct two school food hygiene inspections per day, but with the additional workload of the School Food Standards check they could now only generally visit one school a day. Another Food Safety Officer reported that due to the extra time pressure of the check, they concentrated on cross-contamination in the food hygiene inspection and did not inspect everything as widely as they previously would have.

The Food Safety Officer survey results also reflected these experiences, with half (9/18) of respondents reporting that the checks had an impact on food hygiene inspections, and 8 out of those 9 stating this was specifically due to time pressure. The other impact on food hygiene inspections reported in the survey was catering staff confusion over what was relevant for the hygiene inspection versus the School Food Standards check.

Applying the check

Consistency of application

In local authorities where there were multiple Food Safety Officers involved in this pilot, they would often set up meetings to compare approaches and discuss queries around checks. This helped to ensure consistency within the local authority by agreeing outcomes. This sometimes involved seeking advice from Public Health teams or the Food Standards Agency. In one local authority, one Food Safety Officer took the lead and trained the other Food Safety Officers, which again increased the likelihood that checks within this local authority would be applied consistently.

It is more difficult to say whether checks were consistent between local authorities. While Food Safety Officers’ reports suggest that the general approach was broadly the same, they did take slightly different approaches to specific questions. For example, there were different interpretations of the question relating to meat products: while some participants understood this to include only processed meat, others included all meat products when counting instances on menus.

One nationwide caterer raised concerns that the check was being applied inconsistently by different Food Safety Officers. They reported that despite offering the same food provision across schools in different areas, the check results they received were varied. In this case, instances of potential non-compliance had been identified in their school food provision in one local authority but not in other areas, suggesting mixed levels of understanding or application of the check amongst Food Safety Officers in different local authorities. This potential inconsistent application risks undermining the perceived validity of results for larger caterers.

“The results were really varied from different EHOs and local authorities – in Wolverhampton they checked it really thoroughly whereas others they must have just looked in the fridge and done a check.”

Private Caterer, National

Length of the check

The length of the check was a difficulty some of the time for 12/18 Food Safety Officers who responded to the survey, and the length of time taken varied depending on factors such as school type and Food Safety Officer approach. In one example, where there was only one catering service in the local authority, the Food Safety Officer conducted the same menu check in each school, so familiarity with the menu made the check faster (around 10-15 minutes) compared with checks that involved looking at a new menu each time. It could also be more difficult for Food Safety Officers and take longer when they realised that different food was being served compared with that published on the menu (for example due to delivery problems); schools would often be compliant if the menu was followed, but issues could arise with substitutions.

To alleviate time pressure, one Food Safety Officer described doing more research before their checks as they realised some of the menus were available on school websites. This sped up the time of the check itself because some questions could be answered in advance of the visit, and questions to ask staff on-site could be prepared ahead of time.

The length of time checks took also depended on how many food provisions the Food Safety Officers looked at. As in Phase 1, there was uncertainty around which provisions needed to be checked as part of the pilot, which led to some variation in approach. Some only checked lunch time provisions, whereas others also looked at breakfast, snack and after school provisions, which took longer.

Similarly, another reason for checks taking longer was where there were multiple food outlets and several different menus in a single school. This was most commonly the case with secondary schools.

Most Food Safety Officers suggested that the reporting process following the check using the online forms was not a major time burden in comparison. Most reported that the changes made to the online form following Phase 2 had streamlined the process and that after doing the form multiple times they could complete it quickly.

Content of the check

Food Safety Officers felt there was still uncertainty and limited guidance for certain check questions. Across the qualitative interviews and the Food Safety Officer survey, three questions were highlighted as being particularly difficult to use in the check, which were also highlighted in Phase 1:

-

Is starchy food cooked in fat or oil provided on more than 2 days each week? (Set A)

-

Is a meat or poultry product provided more often than permitted? (Set B)

-

Are more than 2 portions of food that has been deep-fried, batter-coated or breadcrumb-coated provided each week? (Set C).

Several Food Safety Officers reported seeking clarification on these questions from the Food Standards Agency. Some were still waiting to hear back at the time of the research, while others had been advised to use the ‘unsure’ response and were reassured that this was still useful data to gather as part of this phase of exploratory research.

During their checks, 8/18 Food Safety Officers stated in the survey that they had noticed other instances of potential non-compliance outside the question set. This was also reported in interviews, where several Food Safety Officers reported noticing instances of potential non-compliance from a different question set to the one they were using. In these instances, some reported speaking with staff on-site and offering them advice, some added this information to the report and passed the information on to the follow-up team, while a minority took no action.

Phase 1 versus Phase 2

All Food Safety Officers interviewed reported that the reduced Phase 2 question sets made it faster to complete the check, which was the intended purpose of the change. 13/17 Food Safety Officers in the Food Safety Officer survey said the reduction in the number of questions in the set had improved their experience of the checks. However, in the qualitative interviews some reported finding the rotation difficult, as they had to remember which set they had used previously, coordinate with colleagues, and print out more copies of the different aide memoires. 7/17 in the Food Safety Officer survey reported that the rotation of question sets made things worse (6 reported little difference and 4 reported it made things better). Only 1/14 reported that they found rotating sets hard and specified in free text that this was because they were not familiar with the questions.

Within the Food Safety Officer survey 13/18 reported having used all 3 question sets (A, B and C) in Phase 2. Of those who had used more than one set (14), 5 said that Set B took longer and 3 that Set A took longer. This supported the findings from qualitative interviews, within which Food Safety Officers consistently reported that Set C was easier and quicker to complete than other sets overall, despite some also reporting difficulty with the deep-fried question within this set as discussed in the previous section.

Some Food Safety Officers did not apply the Phase 2 question sets as intended. Some asked questions from Phase 1 or other Phase 2 sets on top of the Phase 2 set they were meant to be using. Knowledge and understanding of all the questions from Phase 1 meant that some Food Safety Officers inadvertently found themselves looking at areas outside their question set, although they did try to focus on the set of questions in hand as they were conscious of adding time onto the check. In terms of reporting, however, generally Food Safety Officers only recorded responses for the three or four questions they were meant to use. Even if they observed what could have been potential non-compliance in a different set, they did not report it on the aide memoire form but sometimes informed the school or a relevant team at their local authority (if this existed). One also reported that instead of rotating the sets they chose which to ask based on the week’s menu. Reasons for why Food Safety Officers did not apply the Phase 2 question sets as instructed sometimes stemmed from confusion around the new approach or forgetting to coordinate with other Food Safety Officers, but other times it was more intentional. This is discussed further in section 4.2.

Other changes made in Phase 2 were less commonly mentioned by Food Safety Officers during interviews, and those who did found the online reporting process to be much improved as it made the process faster and reduced duplication of work. 14/17 Food Safety Officers welcomed receiving a copy of the online check results. The extra guidance given in the aide memoire was also helpful but could be further improved, as illustrated by the uncertainty around some of the questions discussed above.

Despite some Food Safety Officers reporting confusion caused by the rotation of question sets, overall feedback in both qualitative interviews and the Food Safety Officer survey showed the changes in Phase 2 achieved their intended purpose of making the checks easier and faster.

Post-check feedback

The level of communication with schools following the check varied and seemed to depend on how comfortable individual Food Safety Officers were with discussing nutrition. Most spoke to catering staff on-site, although some did not speak about outcomes with anyone, with their only communication of results being through leaving a copy of the report. Some went further and sought out head teachers or catering managers, and some followed up with caterers by email too.

The most commonly reported barrier to Food Safety Officers’ follow-up communication with schools was that staff were not available on-site, when the check took place as part of an unannounced inspection. This was mentioned by Food Safety Officers during qualitative interviews and reported by 7/18 who completed the survey. While catering staff tended to be present at the checks, those who Food Safety Officers felt had a greater ability to enact change, such as managers and headteachers, were often unavailable or focused on other priorities.

"The people you’re inspecting and talking to in the school kitchens, they’re just doing as they’re told. It needs to be the people higher up that are doing the orders, picking the suppliers and ingredients.”

Food Safety Officer

Following up with caterers by email was extra work and not all local authorities had the resource to do this. Additionally, not all Food Safety Officers felt confident in communicating about nutritional matters with schools. For example, one Food Safety Officer reported being wary about giving too much advice to schools because they were not a nutritionist but had suggested basic swaps to address instances of potential non-compliance.

From the schools’ perspective, experiences of delivery of the check results were mixed. Most schools in the school survey reported that the Food Safety Officer had shared results with them on the day of the check (38/41). Some had received a handwritten report from the Food Safety Officers following the check and others had received only verbal feedback. Although for some this feedback was useful, others felt it lacked authority compared with a digital report. A minority of schools and caterers reported receiving a local authority follow up (14/34), most often consisting of an email copy of their results.

"[The Food Safety Officer] gave me some advice for things to take off and change [on the menu]…she was really helpful.”

Catering Manager

The exploratory nature of this pilot meant that a formal and consistent delivery and follow-up process was not established, as one of the pilot’s aims was to understand what follow-up actions were feasible for local authorities. Whilst intentional for the pilot, not having a formalised process may have led to confusion or undermined the authority of checks for some.

Overall perceptions of the pilot

Consistent with Phase 1, Food Safety Officers were positive about the pilot overall. They felt that the pilot has proven it is feasible for them to conduct the checks on the School Food Standards alongside food hygiene inspections, although some raised capacity concerns if the checks were to continue. Food Safety Officers generally felt the check was a good fit with their role in Environmental Health and found it an enjoyable process. They also felt that it had improved relationships between key actors, including between and within local authority teams, with schools and private caterers.

Some Food Safety Officers expressed that while they had been happy to take the checks on for the duration of the pilot to help assess the new approach, continuing might not be viable if it became a permanent part of their role that they would have to account for. For some Food Safety Officers, this reservation was compounded by their sense that they were unclear about the extent to which the pilot had enabled positive change. As a result, they were unsure whether their local authority would want to continue with the pilot, due to the costs (time and resources) associated with the pilot.

4.2. Results of the checks and discussion

There was variation in the proportion of schools with potential non-compliance across local authorities, as well as in the standards being marked for potential non-compliance. As also discussed in the Phase 1 report, it is possible that differences in approach to the checks by Food Safety Officers (outlined in section 4.1) may also have contributed to some of the variation in levels of potential non-compliance detected across authorities.

Primary versus secondary schools

Participants interviewed in Phase 2 reported that typically primary schools received no or few instances of potential non-compliance and it was more common for secondary schools to have multiple instances of potential non-compliance raised, although some did not.

This may be due to challenges with school food take up. Pupils in secondary schools may be more likely to eat off site (if school policy permits pupils to leave the premises). In this last example, in-school provisions are competing with high street offerings. To compete, secondary schools might provide certain foods that could be potentially non-compliant where schools and caterers perceive students are more likely to buy these foods. For example, one secondary school had multiple instances of potential non-compliance across multiple aspects of their food offer and a key issue identified was that the school is situated next to two popular fast food chain restaurants.

“The school does take a balanced view with what is on sale, due to students having no restriction on what they bring into school and proximity to the centre of town with all the food choice freedom that offers.”

Catering Manager

In comparison, participants reported that primary schools had more control over their offers as there were a set number of choices on the menu, break options were much less commonly offered, food items brought from home were often monitored and children could not leave the premises. Overall, this could contribute to primary schools finding it more straightforward to be compliant with the School Food Standards.

Because of these differences, some Food Safety Officers felt that while the Phase 2 question sets were good for primary schools, which generally had fewer instances of potential non-compliance, they were insufficiently detailed for secondary schools, where the school food picture tended to be more complicated.

Specific questions

Across all local authority participants and Food Safety Officers interviewed, some check questions were reported to have higher rates of potential non-compliance than others. Set C was consistently reported to be the easiest set of questions for schools with which to be compliant. Nearly all (especially primary schools) were compliant with the following set C questions:

-

Are confectionery, chocolate and chocolate coated products available?

-

Are non-permitted drinks available?

Questions that had higher rates of potential non-compliance were:

-

Is oily fish provided at least once every three weeks at lunch?

-

Is a meat or poultry product provided more often than permitted?

-

Is starchy food cooked in fat or oil provided on more than 2 days each week?

Phase 1 versus Phase 2

Most Food Safety Officers and local authority participants interviewed felt that the reduced question sets and rotation negatively impacted the quality of the compliance data collected. Although they recognised that it made the checks faster and simpler as intended, they felt fewer questions did not always capture the full picture of compliance or potential non-compliance of the school food offer. Some Food Safety Officers in the qualitative research reported they would have preferred to ask more questions rather than risk reducing the quality of the data (as they perceived the smaller question sets did). Indeed, as discussed in section 4.1, some Food Safety Officers did stray from their question set to ask additional questions.

The perceived negative impact of the Phase 2 changes on the overall checks data was perhaps driven by a misunderstanding of the aim of the pilot by Food Safety Officers and local authorities. Many local authority and Food Safety Officer participants assumed that a key purpose of the pilot was to collect data nationally, and they felt that the Phase 2 changes undermined this effort. They saw the rotation of question sets to have reduced the comparability of the data so that it could no longer be used to investigate patterns of non-compliance nationally. Arguably, this was also the case in Phase 1 as two different groups of questions were used, but it may not have been recognised by participants as they only interacted with one of the groups.

Many Food Safety Officers reported that outcomes varied by which Phase 2 question set was used, meaning they questioned the fairness to schools of rotating the question sets if one set was ‘easier’ than the others.

“Question Set C was too easy, when schools got set C it felt like they still might be non-compliant even when they passed.”

Public Health

4.3. Response to the checks

This section summarises how schools, caterers, and local authorities responded to the data and process of conducting the check. It outlines cases where positive change was made to school food provision following the checks, and cases where no action was reported to have been undertaken following the identification of potential non-compliance and the barriers that contributed to this.

The model for the pilot assumed that local authorities would contact schools to address instances of potential non-compliance through local authority follow-up. However, many schools interviewed reported no local authority follow-up after the checks beyond being emailed a copy of their results. This was supported by the school survey, where 12/63 school staff surveyed were not aware there had been a check at their school and 20/34 schools reported that they had not received any follow-up from the local authority after the check.

This was the case for the private caterer participants as well, who also reported no local authority follow-up with them after the checks. In some cases, caterers reported not having been aware checks had taken place in a school under their provision at all.

Some local authority participants reported instances of substantial follow-up with schools including offers of support, but there were no direct accounts from any of the specific schools or caterers interviewed about how they had engaged with local authorities to make changes to their provision. This is most likely due to the fact that local authority participants and school/caterer participants represented different samples and only a small number of schools and caterers were interviewed. Therefore, the response to the checks section is split into how schools reported responding to the checks and how local authorities reported responding, to reflect that these were distinct for our samples.

Response to the check from schools

According to the model for the pilot, schools could have interacted with the pilot at several different stages. This includes:

-

Pre-check: All schools in the pilot local authorities received an email about the checks occurring in the 22-23 school year.

-

Receiving a check: If they received a food hygiene inspection during the pilot period, food business operators within schools should have received a check and school or catering staff on-site at the time may have interacted with Food Safety Officers as part of this.

-

Post-check: The local authority may have engaged with the school about the results of the check.

-

Changes to provision: Schools could engage with available support or independently choose to change their school food provision.

Outcomes from the check

School participants in interviews reported one of three types of outcomes in response to a check taking place: 1) making specific changes to address areas of potential non-compliance; 2) making broader changes to improve school food provision; and 3) taking no action, which was more likely when no instances of potential non-compliance were marked in the check. When changes were made, they typically followed a review of school food provision which either took place internally or with an external party (e.g. with the catering company or an accreditation body).

Out of the schools that responded to these questions in the school survey, a majority reported either reviewing their school food provision internally (18/44) or with an external party such as a private caterer or accreditation body (14/44) following the check. Of those who conducted a review, two thirds of these schools reported that they ended up making changes to their school food provision (20/33) or planned to (2/33).

Local authority participants observed that the existence of the check had raised the profile of the School Food Standards, made some schools aware of their legal responsibilities, made the School Food Standards more salient where they had not been considered recently and encouraged schools to prepare for potential future checks.

Outcome 1 – making specific changes

Amongst schools interviewed, the most common outcome was that they had made specific changes following the check.

In describing the changes made, this included changes to lunchtime menus, through adding items (for example, oily fish) or reducing the frequency of items (such as meat products or pastries). It also included changes to break time offers by:

-

Removing certain items, for example, juice, rice crispy treats.

-

Replacing specific ingredients to remove certain items such as replacing chocolate pieces with cocoa powder in cookies.

-

Adding certain items, like fruit pots.

This outcome was often seen when the catering manager was supportive of the School Food Standards and had the ability to directly change menus (which was more common when catering was in-house). These catering managers typically reported that they had been unaware of the potential non-compliance prior to the checks and had aimed to address these instances as soon as they were made aware following the check.

Outcome 2 - making broader changes to improve school food provision

In rare instances, additional changes outside the checks were planned or implemented. Interviews suggested that this occurred when individual school managers used the check as an opportunity to raise awareness of the School Food Standards with the senior leadership team and promote wider changes to improve school food provision. One school survey respondent also reported making wider changes to school food provision by using the checks as an opportunity to obtain accreditation for the quality of their school food from an external organisation.

Outcome 3 – taking no action

Another reported outcome following a check was that no changes were made to school food provision. Of the 44 schools that responded to these questions in the school survey, 9 did not review their food provision. 11/33 schools that reviewed their provision stated they had not made changes and did not plan to, although some of these cases reflected that fact that these schools did not have any instances of potential non-compliance identified at the check.

Local authority participants cited several instances of speaking to catering managers who decided against making any changes despite instances of potential non-compliance being identified at the check. The reasons for making this decision included satisfaction with the current offer, feeling the instances of potential non-compliance were incorrect, feeling students would not eat compliant food, or believing that changes would have additional costs. In other cases, school catering managers or leadership teams felt changes were the responsibility of their caterers who did not go on to make any changes.

Pre-existing good practice

Prior to the checks, there were some examples of good practice to encourage healthy eating being implemented in the schools interviewed. A few schools and caterers reported several actions they had already taken prior to the check to support compliance with the School Food Standards. This included using external services to certify their menus, having a checklist to hand when developing menus (taken from the GOV.UK School Food Standards resources page), and training with cooks to refresh their knowledge of the School Food Standards.

Responses to the checks from local authorities

In addition to ascertaining whether the checks could identify potential non-compliance, another key aim of the pilot was to test whether local authorities would be able to offer support to schools in response to any potential non-compliance that was identified.

The teams involved in the pilot and how they were structured varied significantly across the 16 pilot local authorities where checks were conducted. The teams that could be involved included:

-

Environmental Health – this team was involved in all 16 local authorities taking part in the pilot. Environmental Health teams were typically responsible for administering the checks and collating the data. The checks were carried out by Food Safety Officers from this team alongside their food hygiene inspections in schools.

-

Public Health – this team was involved in 8 of the 16 pilot local authorities. Public Health teams were typically responsible for following up with schools and caterers about the check results. Sometimes this team would sit at the County Council level.

-

Specialised School Food Teams – this type of team was involved in 3 of the 16 pilot local authorities. These teams have expertise in supporting school food provision, which meant that in the context of the pilot they could offer targeted support to individual schools.

The response by the 16 pilot local authorities administering checks was broadly one of the three types of outcomes outlined below, depending on which teams were involved. This typically was the main determinant in whether and how these local authorities were able to respond to the checks and resolve any instances of potential non-compliance.

-

Outcome 1 – 5 out of 16 cases - Environmental Health only.

-

Outcome 2 – 8 out of 16 cases - Environmental Health and Public Health.

-

Outcome 3 – 3 out of 16 cases - Environmental Health and School Food Team.

In addition to these broader outcomes based on which local authority teams were involved, there was also variation in terms of whether the following were involved and to what extent:

-

Local authority catering – around half of the pilot local authorities interviewed reported having a local authority-run school food catering offer. Local authority catering was the main provider of school food in some local authorities, while in the others provision was also split across private and in-house caterers. The Discovery research report includes ‘Current Context - Caterers’ for additional context around school catering provision.

-

External organisations (involved in school food) – a minority of pilot local authorities contracted or involved external organisations working in school food to support the follow-up process for the pilot.

Outcome 1 – response by Environmental Health only

In 5 out of 16 of the local authorities conducting checks, Environmental Health were the only team involved. These local authorities reported that communication with schools following the check was limited to leaving or sending a report of the check results with schools. They were not able to offer any specific advice or follow-up support as they did not have the capacity or nutritional expertise to do so. Some teams had a discussion with their local authority catering service where it existed, but they did not report engaging with private caterers and there were no plans to do so. Some requested further guidance from the Food Standards Agency or Department for Education about what this feedback process should look like and whether there was support that could be offered to schools from outside the local authority.

Several Environmental Health participants in these local authorities questioned the pilot as a whole, especially whether the benefits of the checks were worth the cost in terms of time, money and effort on their part. Several of these teams also reported that most schools in their local authority had no instances of potential non-compliance found during the pilot, which also made the checks less of a priority from their perspective.

“In an ideal world it would be someone else’s responsibility for doing these checks. I’m not sure if it’s worth the money to conduct all these checks when most schools are already trying their best to be compliant.”

Food Safety Officer

In most of these local authorities, there was typically a Public Health team that was not involved in the pilot as they also did not have capacity or expertise. According to the Environmental Health participants, a few of these Public Health teams planned to be involved once results from the pilot were better understood.

Overall, these local authorities had the least substantial follow-up process, due to their limited capacity and expertise. For them to be able to offer more substantial support to schools in response to potential non-compliance, they may require support from outside the authority, whether from central government or other relevant external organisations.

Outcome 2 – additional Public Health involvement

In 8 out of 16 of the local authorities conducting checks, Public Health teams were involved in the pilot alongside Environmental Health. There was greater variation in these local authorities in comparison to Outcome 1, as the extent of Public Health’s involvement, which involved responsibility for the individual follow-up process, varied between local authorities. All the Public Health teams interviewed received the checks data and sent follow-up emails to schools summarising instances of potential non-compliance, offering advice for menu changes, and links to online guidance. Beyond this, their involvement varied depending on several key factors, namely: their prior relationship with the Environmental Health team before the pilot started, their capacity, and whether school food was a strategic priority for the local authority.

Firstly, a strong prior relationship with Environmental Health typically meant that the Public Health team was more involved in the pilot. These teams tended to be involved from the first phase of the pilot and were often the team that Environmental Health went to when they had any queries about the check. When there was a less strong relationship, Public Health had often been brought in halfway through the pilot to support on the follow-up process and so were less involved.

Capacity was another factor that affected Public Health’s level of involvement. When Public Health teams had more capacity, they were able to take on more time-consuming follow-up processes. For example, two Public Health teams had a Public Health nutritionist go on visits with Food Safety Officers, although this was not the intended design of the pilot. The nutritionists helped to support the administration of the check and talked to school staff on-site. This avoided areas of uncertainty in the check questions, as these could be resolved by the nutritionist, and made it easier to engage schools in a conversation about any potential non-compliance as it was in-person. Another Public Health team had the capacity to follow up initial emails to schools with a phone call to discuss whether they had addressed the potential non-compliance. This team felt this was necessary as they had not received responses back to their initial follow-up emails from schools. This finding was echoed by most local authority participants, who reported that follow-up emails sent to schools were rarely replied to and had not led many schools to engage with offers of support.

“It has been absolutely positive, however I do think it is because we had the opportunity to send in a nutritionist. Other authorities with just EHOs may have struggled, as there was quite a lot of work involved.”

Public Health

A related factor was the extent to which school food was reported by the local authority to be a strategic priority for the local authority. Some local authorities had publicly highlighted school food or children’s nutrition as a key priority in external reports or talks. When this was a strategic priority, Public Health teams would often have a nutritionist working on the team who was able to offer more advice on menu changes to address potential non-compliance. In some of these cases where there was more capacity and school food was a priority, teams also offered to set up meetings with schools and caterers to provide specific guidance and support

Beyond individual follow-ups with schools and caterers, some Public Health teams also used the checks to promote strategic change within the local authority on school food and children’s health. Examples included a team that added school food as a key priority in their healthy weight strategy report, one that reported collating and disseminating results in the local authority to raise awareness and inform planning, and one that reported offering training for governors, trustees and headteachers.

Overall, the existence of Public Health teams at either the district or county council level in a local authority meant there were often more substantial responses available to address potential non-compliance for individual schools when this team had capacity and nutritional expertise. However, suitable capacity within the Public Health team and joined up working between Environmental Health and Public Health teams was also necessary to deliver effective follow-ups. In addition to these individual follow-ups, some Public Health teams used the checks data to inform broader conversations and changes, which they saw as an important opportunity for them strategically and as a potential route for creating larger scale change across the local authority.

Outcome 3 – additional specialised school food team involvement

In 3 out of 16 of the local authorities, a specialised school food team was involved in the pilot alongside the Environmental Health team. These teams sat at the county council level in the 3 cases of this outcome observed, although not all county councils involved in the pilot fell under this outcome (as some Public Health teams involved in the pilot sat at the county council level).

These local authority teams could offer tailored and comprehensive support to schools and caterers to address potential non-compliance. The services they offered included: reviewing schools’ pre-existing menus for advice on compliance, offering their own compliant menus, auditing school provision multiple times a year to ensure compliance, and offering School Food Standards training. These teams reported that they had the capacity and expertise to offer bespoke one-on-one support from a member of the team to schools and caterers, if they chose to use the paid service.

If schools and caterers did engage post-check, these teams offered the most substantial follow-up process out of the 3 outcomes and reported they were confident that they would be able to address any potential non-compliance raised by the checks. Two of these teams also reported that a positive aspect of the pilot was that it had helped to validate the effectiveness of their offer. Those schools that already engaged with their services had not received any instances of potential non-compliance. They were also pleased that the pilot had raised awareness of the School Food Standards in general and of the existence of their service.

“It’s given the authority quite a lot of kudos, all our schools were compliant, which was expected, but having spot checks by the pilot has raised everybody’s interest again.”

Specialised school food team

However, these teams reported mixed success at engaging schools and caterers with offers of support to address any potential non-compliance raised by the checks. One team reported that they had engaged with several new secondary schools and private caterers. This team had waived the cost of their services for the duration of the pilot and followed up with schools by email and phone, which may have boosted engagement. The other two teams reported that they had not seen much additional engagement with their offer following the pilot. One team was cautious about directly contacting schools about instances of potential non-compliance, as they believed this was the governors’ or trustees’ responsibility to address as they felt appropriate.

Overall, there were additional barriers that restricted the follow-up process even in these cases where specialised teams existed. Additional support or guidance may be needed to ensure that where substantial support exists it is easily accessible to schools.

Responses involving other teams

Outside of these three broad outcomes based on which local authority teams were involved, the responses to checks also varied depending on whether local authority catering teams or other organisations external to the local authority had been involved.

Around half of the pilot local authorities had a local authority-run school food catering offer that schools could choose for their school food provision. The uptake of local authority catering between pilot local authorities with this offer varied from a small minority of schools within an authority to almost all.

Local authority participants generally reported that existing relationships with local authority catering teams made the follow-up process easier when potential non-compliance was marked at schools under their provision.

Most teams that received the checks data in one of these pilot local authorities reported that they directly engaged local authority catering services in ongoing discussion regarding the check. In one case they were involved in the pilot itself and helped the Environmental Health team resolve queries about the check (although the Environmental Health team acknowledged there was a potential conflict of interest here). Local authority participants reported that there was typically a pre-existing working relationship with the catering team, which meant it was easy to engage in discussions about the check whenever potential non-compliance was marked. In most cases, local authority participants reported that these teams were open to suggestions, although there were a few instances where they pushed back on certain instances of potential non-compliance when there was some uncertainty (see Section 4.1 Content of the check).

Local authority participants also reported that in general it appeared that fewer instances of potential non-compliance were raised in schools with local authority-run catering and that these schools were easy and quick to check as the local authority catering menu tended to be the same across schools.

Due to the greater ease of communicating and engaging with local authority catering services in general, tackling potential non-compliance in this context tended to be both easier and more effective than where school food was delivered in-house or via private caterers. In these contexts, local authority participants were more reluctant to engage with non-local authority-catered schools without more guidance or reported that these caterers were unwilling to engage with them.

“We have a good working relationship with local authority catering, so we brought the instances of potential non-compliance to their attention directly. We weren’t going to pick it up with any private caterers without further steer from the Food Standards Agency or the Department for Education.”

Environmental Health

There were also some instances across the pilot local authorities where participants mentioned external organisations involved in school food either as part of the current follow-up process or as suggestions for a future strategy for addressing potential non-compliance. These external organisations mentioned were available to help support the follow-up process and address potential non-compliance, but typically their services require funding from either the local authority or the school itself. In addition, participants mentioned that a potential issue with using external organisations was that different providers demand different standards for their awards and pledges.

Barriers to addressing potential non-compliance

Although the participants in schools, catering companies, and local authorities reported cases where instances of potential non-compliance were being addressed and changes being made to school food provision, they also reported instances where potential non-compliance was not addressed.

This section outlines the common barriers to addressing potential non-compliance that were highlighted by participants.

Barriers affecting schools and caterers

Awareness of responsibility for the School Food Standards

The first barrier at this level was limited perceived responsibility for the School Food Standards on the part of both schools and caterers. Many local authority participants felt that the school leadership board (headteachers and governors/trustees), were not fully aware of their responsibilities regarding the School Food Standards, did not focus on them or did not feel accountable for potential non-compliance. They evidenced with the fact that they received very few responses from their follow-up emails to schools after the check.

“Reports that went to us also went to schools, including ones that said there might be potential flags, and no schools came back to us with any questions. That is pretty telling, it just isn’t a priority for them.”

Local authority caterer

School leadership teams tended not to have strong oversight over school food provision overall and, where they did, tended to focus this on uptake and costs, which in some reported cases meant adding in certain food items that would result in instances of potential non-compliance. Some had the perception that caterers or catering managers would be responsible for compliance, which limited their willingness to make changes to provision or engage with the follow-up process for the checks.

External caterers had high awareness of the School Food Standards and felt that the onus to uphold them rested largely on them, despite schools’ responsibilities. As a result, they reported prioritising compliance when creating and developing menus. In their view, they felt that instances of potential non-compliance on their menus were typically at the specific request of schools, for example to avoid including food that was less popular with children.

Awareness of the outcome of the check

Communication of checks data to those with ultimate responsibility for food provision (governors/trustees) was commonly indirect. When conducting checks on-site, Food Safety Officers typically spoke to the catering staff and catering manager in kitchens but not school leadership and when catering was provided by an external private caterer, there tended not to be a representative on-site. As such, it was often the responsibility of catering managers to report back on the checks to school leadership teams which may not have happened due to the limited oversight from school leadership outlined earlier. It is unclear from this research the extent to which private caterers were engaging with school leadership about instances of potential non-compliance, but the evidence suggests that this is likely to be in a very limited way.

When local authority teams followed up by email after the check, they typically contacted the catering manager directly or used the school’s generic email address, asking for the email to be forwarded onto relevant staff members. There is no guarantee that this always happened and so it is possible that these were not always seen by the school leadership team. In addition, private caterers typically were not communicated with directly by local authorities as they are third parties, which meant the checks data would have to come to them through the school. This was supported by the fact that most schools and private caterers interviewed reported no local authority follow-up after the checks, and in some cases, caterers reported not having been aware checks had taken place.

Scope to make catering changes

For action to be taken following the check, the school and caterers had to have the ability to make changes to their school food provision. Some catering managers reported that the preferences of the students prevented certain compliant menu items from being added as students would not eat them. A commonly cited example of this was the oily fish requirement: several catering managers reported that they had tried many ways of serving this option but that it was rarely chosen by children, resulting in food waste and a perception that it was a waste of money (due to the expense of oily fish).

Beyond the requirement of the students, this barrier could also occur due to business factors. Some catering managers suggested that they could not take on the extra costs associated with a fully compliant menu, as they were already operating at low margins. Alternatively, they suggested that they needed to include profitable menu items to subsidise the rest of the menu so would not be able to remove them, leading to potential non-compliance. Others working with external caterers reported they were in a fixed-term contract in which the catering provider was responsible for menus, so would not be able to change their menu provision at this point in time.

Engagement from stakeholders

Having multiple stakeholders involved often made addressing instances of potential non-compliance more complicated as they all had to be engaged in the process. The number of stakeholders varied depending on catering arrangements. With in-house catering offers, changes only involved the school leadership team and catering manager, which could make addressing potential non-compliance a more direct and efficient process. Some of the in-house catering managers interviewed were highly motivated to be compliant and were quick to make changes to menu provision following instances of potential non-compliance.

Situations where more stakeholders were involved, such as when private external caterers were the school food providers, were often more difficult to address. For example, specialised school food teams reported that their services required both the school and its external caterer to engage with them, to provide menus, information on cooking practices and specific recipe nutritional information. This meant that a school could not make the decision by itself to engage with support. More stakeholders with differing responsibilities and priorities made it less likely that all of these would be aligned and supportive of the need to make changes to food in the school.

Other constraints on schools

Many school, catering and local authority participants emphasised the current pressures on schools, such as consideration of food costs and difficulties with funding. They also highlighted that school food provision was pressurised by shortened lunch times, a ‘grab and go’ culture, and having to compete with off-site providers. They cited these competing priorities as a potential explanation for the limited engagement around the School Food Standards in general, as well as around the pilot follow-up process specifically.

“Some schools have capacity and can engage [with support]. Other schools are stretched and have other pressures, meaning areas not being checked will slip down their priority list.”

Public Health