1. Acknowledgements

Profuse thanks go to Rees Bramwell, David Woodhead, Linda McAra, Marc Johansson, Matthew Daniels and the rest of the Compass team for their strong support. Thanks also go to Brian Cook for his methodological assistance. Additional immense thanks to Alice Rayner, Anya Mohideen, Harriet Pickles, and Phil Jones for their contributions to this work.

2. Executive Summary

2.1. Background

The marketing industry spends a lot of money on sales promotions (temporary offers or campaigns, designed to increase sales) on food products, such as offering free samples of products. However, there is very little published peer-reviewed evidence about whether this activity is effective and, if so, whether the effect is sustained after the promotion ends.

Free samples may be particularly useful to introduce new food products, since taste is one of the most important determinants of food choice. In particular, retailers want to increase sales of plant-based (vegan or vegetarian) products. For example, Tesco has a target of increasing sales by 300% from 2020-25. Similarly, in the out-of-home sector, companies like Starbucks and Burger King are committed to increasing their plant-based offerings. One reason people give for not wanting to buy plant-based products is being worried that they won’t like the taste. This may be particularly true for low socio-economic status groups, who eat less plant-based food (making them a potential target market) and may be less likely to considering buying plant-based food than other groups.

Eating is often driven by habit, so uptake of new products may also depend on forming new habits. There is some suggestion that loyalty cards can increase sales of plant-based products in university food outlets, but that was not evaluated using a controlled trial.

Therefore, the FSA commissioned the Behavioural Practice to conduct a randomised controlled trial with a process evaluation, to investigate whether free samples of plant-based foods and a loyalty card with ‘endowed progress’ can increase the purchases of plant-based meals in a blue-collar workplace cafeteria environment (cafes and food outlets).

2.2. Methods

We conducted a stepped wedge trial with a process evaluation. This trial was delivered via a workplace food outlet operator in blue-collar workplaces across the country. The trial ran over four weeks, from 1st - 28th August 2022 (see Figure 1). Food outlets were randomised to transition from control to intervention in three ‘sequences’ that entered in three steps, in Week 1 (1st August), Week 2 (8th August) and Week 3 (15th August). All food outlets supplied baseline data for the four weeks prior to the trial (4th – 31st July 2022) and five weeks of data after the intervention had been withdrawn (29th August – 2nd October 2022). We used a stepped wedge design to maximise power given the number of outlets that agreed to take part. There were 29 sites that completed the trial, 9 in the first sequence and 10 in both the second and third.

In the first week of the intervention, we gave out free samples of one of the vegan or vegetarian meals on offer that day in the food outlets (the meals on offer varied by outlet). We sent a fieldworker into the food outlets to hand out free samples at lunchtime on the Tuesday, Wednesday and Friday (the days of the week with highest footfall).

In each food outlet, loyalty cards were made available for the duration of the intervention period, which could last for two, three, or four weeks depending on when a site entered the intervention. Customers received a stamp for each vegan or vegetarian hot meal or baguette they ordered during the lunch and dinner periods. Once customers had collected four stamps, they could exchange the card for any meal of their choice, vegan/vegetarian or otherwise, until September 25th 2022 (one month after the end of the intervention period). However, the first stamp was given as ‘endowed progress’, so in practice, customers only needed to purchase three qualifying meals to receive a free meal.

For the process evaluation, interviews were conducted with food outlet managers and staff from six food outlets, and six fieldworkers who handed out the free samples and loyalty cards in those outlets. Intercept interviews were conducted with customers at two sites in each sequence. Manager, staff and fieldworker interviews were charted using a thematic framework to analyse the delivery and impact of the intervention.

2.3. Results

We did not find any statistically significant effects of the interventions on the volume of plant-based sales. The volume of plant-based sales on days when free samples were handed out was not different from that of the baseline period (coefficient = -0.53, 95% CI [-3.43 – 2.36], p = .718). Nor was the volume different on days with the loyalty card intervention only (coefficient = 0.33, 95% CI [-2.73 – 3.38], p = .834).

Amongst Sequence 1 (4-week intervention period), on average, 14.5 plant-based meals were bought per day during the baseline period (23.1% of total sales) compared to 16.9 plant-based meals per day during the intervention period (25.3% of total sales). In Sequence 2 (3-week intervention period), on average, 20.8 plant-based meals were bought per day during the baseline period (31.5% of total sales) compared to 19.9 plant-based meals per day during the intervention period (30.4% of total sales. In Sequence 3 (2-week intervention period), on average, 21.3 plant-based meals were bought per day during the baseline period (36.2% of total sales) compared to 20.3 plant-based meals per day during the intervention period (38.0% of total sales).

The implementation and process evaluation revealed that the free samples had been handed out as expected, without undue burden on the food outlet staff. Footfall may have been relatively low at lunchtime and customers rushed because they had short lunch breaks. Customers often did not take the free sample, but those who did tended to say that they liked the food. Nevertheless, they preferred their usual meal or had brought their own lunch from home. There was a perception that the loyalty cards were not well used and were more likely to be taken up by vegetarian customers. Interviewees said reach would have benefitted from better advertising in food outlets, for example posters or flyers about the loyalty scheme.

2.4. Conclusions

Neither intervention was effective. Workers who tried the free samples seemed to like them, but there was no evidence of an increase in purchases. The loyalty cards were not utilised very often and it seems that many customers were not aware of them. This study contributes to a small literature that suggests that free samples do not increase purchases of the sampled product, at least not without other supporting interventions. It suggests that for loyalty cards to be effective, then they need promotion to support their introduction.

3. Introduction

3.1. Background

The marketing industry claims that $2.2 billion dollars were spent on general product sampling in 2009 (Linchpin SEO, 2019) and that it was still on the rise in 2015 (Heneghan, 2015). A lot of claims are made about the effectiveness of this technique by people who are offering their services, such as that sales conversions reach up to 90% for some products (Does Giving Free Samples Increase Sales?, n.d.; Gomez and Kelly, 2013). However there is surprisingly little rigorous empirical testing of the effect of free samples and what evidence exists is somewhat mixed (Nin Ho & Patrick Gallagher, 2005; Oly Ndubisi & Tung Moi, 2006).

Free samples may be especially useful when a business wants people to take up a new product that they haven’t used before. Free samples could be particularly important for food products, since the two most important determinants of food choice are price and taste (Osman & Jenkins, 2021). Therefore offering samples may be helpful to introduce consumers to new products that they would not normally purchase.

One type of new product that marketers are interested in promoting is vegetarian or ‘plant-based’ food. UK sales of meat-free and plant-based dairy products have roughly doubled from 2016-2020, and are now worth close to £600m each (Glotz, 2021). Retailers continue to want to increase sales, with Tesco setting a target of a 300% increase in sales of plant-based food from 2020 to 2025 (Smithers, 2020). Similarly, in the out-of-home sector, companies like Starbucks and Burger King are committed to increasing their plant-based offerings (Jones, 2022).

However lower socioeconomic status (SES) groups eat less plant-based foods than higher SES groups and they may be less likely to change their diet (E. J. Lea et al., 2006; Pohjolainen et al., 2015). The FSA’s Food and You survey on eating trends found that in 2022 half (50%) of people who are in lower supervisory and technical occupations said that they have never eaten meat alternatives, compared to a third (34%) of people in managerial, administrative and professional occupations (Armstrong et al., 2022). The lower supervisory and technical occupations group are also less likely to say they made a change to eat less meat or poultry or fish in the last 12 months (20%, compared to 33% of those in managerial, administrative, and professional occupations) (Armstrong et al., 2022). This suggests that there is the potential to market plant-based foods to these groups and further increase sales.

Eating behaviour is often driven by habit (Taufik et al., 2019). A number of surveys show that habit and taste may be particularly important for the purchase of plant-based food, with respondents not particularly looking to alter their consumption habits and being worried they won’t enjoy the taste (Fehér et al., 2020; Graça et al., 2015; E. J. Lea et al., 2006; E. Lea & Worsley, 2001, 2003; Rosenfeld & Tomiyama, 2020)). In terms of taste influencing purchase, several empirical studies have found that labelling that aims to make food sound tasty can increase purchases of plant-based food (Swahn et al., 2012; Turnwald et al., 2017). If consumers are worried that they won’t like the taste of the product, offering a free sample may be an effective way to overcome this.

Although they are widely used, the evidence base on the effectiveness of sales promotions (temporary campaigns or offers) is limited, especially free samples. There is some evidence that samples impact sales when they were attached to newspapers and combined with price discount coupons (Bawa & Shoemaker, 2004). When used in-store at point of purchase, one study that used a self-report measure found that participants said they would be encouraged to buy a product after sampling. (Oly Ndubisi & Tung Moi, 2006), However, others that investigated actual purchasing behaviour found that they are not effective (Lammers, 1991; Nin Ho & Patrick Gallagher, 2005) . Further, the literature base seems to be confined to coupons on newspapers or in food shops (Hawkes, 2009), whereas people may eat a large proportion of their meals in the workplace. Workplace food outlets also present an opportunity to intervene on purchases at point of consumption, not simply point of sale (Allan et al., 2017; Clohessy et al., 2019). Therefore, they may be effective places to introduce interventions that are designed to change eating behaviour.

Unlike free samples, it is quite well-known that price discounts impact purchases (Santini et al., 2016). What is less clear is whether the effects of discounts can be sustained after they are withdrawn. For instance, in the food outlet space, Horgen and Brownell (2002) ran an experiment on a price promotion in a cafe. During the promotion, the price of the target items was decreased by approximately 20%–30% and sales of the items increased. However, sales decreased again after the intervention was withdrawn. This result is consistent with a general finding that, although sales promotions lead to significant sales increases over the short-term, this does not necessarily lead to long-term changes in food-consumption patterns (Hawkes, 2009). Loyalty schemes, where people get free goods after making a certain number of purchases, may be more effective than price discounts. Chan et al. (2017) found that behavioural rewards such as a reward-points programme, which gave points for healthy items that could later be redeemed for discounts increased intention to purchase a healthy food more so than financial discounts did. In a supporting field trial, they also showed that healthy food sales were higher during the reward intervention than the price intervention (for example, there was a 28.5% increase in salad sales with the behavioural reward compared to 5.5% increase with price discounts). The use of loyalty cards to incentivise the consumption of plant-based food seemed to have some success in a university food outlet; although the approach has not been evaluated through a controlled study (Friends of the Earth, 2020).

There are various reasons why loyalty schemes may be effective. Chance et al. (2014) speculate that cards may be more effective than price promotions because they connect a financial incentive with a sense of progress towards a goal, combining extrinsic and intrinsic motivation. Loyalty schemes may also be better at encouraging repeat purchases than a one-off price discount (Berman, 2006). They can be enhanced by using the endowed progress effect, whereby giving people a sense that they have advanced towards a goal makes them more likely to achieve it (even if no real steps have actually been taken) (Nunes & Drèze, 2006). For example, a loyalty card where a customer needs to collect ten stamps, which is handed to the customer with two stamps already completed, may lead to greater completion than an eight-stamp loyalty card—even though in both cases the customer only had to make eight purchases to complete the card (Nunes & Drèze, 2006).

Therefore, it is of interest to test whether free samples and loyalty cards can be effective at encouraging customers in workplace food outlets to purchase more plant-based meals. Free samples could help customers to learn about the taste of the plant-based meals and thus overcome the barrier of thinking that they won’t like the taste of plant-based food. Loyalty cards address the barrier that consumers are in the habit of eating meat via giving them an incentive to purchase the plant-based meal repeatedly, and therefore to form new habits. Both interventions use a number of behavioural change techniques (as classified in the Behavioural Change Technique Taxonomy (Michie et al., 2013). According to the COM-B model (Michie et al., 2011), which stresses the need for capability, opportunity and motivation in order to change behaviour, the interventions both involve the domains of reflective decision-making and physical opportunity. See Table 1 for details.

3.2. Objectives

The aim of the study was to investigate whether free samples of plant-based foods and a loyalty card with endowed progress can increase the purchases of plant-based meals in a blue-collar workplace cafeteria environment (cafes and food outlets).

In order to answer this question, the research team conducted a field trial to test the following hypotheses:

-

H1. In a blue-collar food outlet environment, offering free tastings and loyalty card promotions on plant-based food options will increase purchases of those foods during the period that the intervention is offered.

-

H2. In a blue-collar food outlet environment, offering free tastings and loyalty card promotions on plant-based food options will increase purchases of those foods after the intervention is withdrawn.

3.3. Process evaluation

We also conducted an implementation and process evaluation, to explore the factors influencing the impact of the interventions (i.e., why the interventions were or were not effective). The qualitative research also explored intervention fidelity (i.e., whether the intervention was delivered as expected) and evaluate the process of implementing the intervention in order to identify learnings and improve future trials.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Trial Design

We conducted a stepped wedge trial with a process evaluation. The trial ran over four weeks, from 1st - 28th August 2022 (see Figure 1). Food outlets were randomised to transition from control to intervention in three ‘sequences’ that entered in three steps, in Week 1 (1st August), Week 2 (8th August) and Week 3 (15th August). All food outlets supplied baseline data for the four weeks prior to the trial (4th–31st July 2022) and five weeks of data after the intervention had been withdrawn (29th August–2nd October 2022). We used a stepped-wedge design in order to maximise power, given the number of outlets that agreed to take part.

4.2. Participating Workplace Food Outlets

This trial was delivered via a workplace food outlet operator in blue-collar workplaces across the country (See Figure 2 for the regional distribution of food outlets). These food outlets were part of distribution centres (central storage and sorting locations from which large organisations distribute their products) for businesses that operate nationally in the UK (one grocery chain and one delivery business). Employees working on the sites can purchase hot and cold meals as well as packaged food products from the food outlets. The food outlets are open every day the workplaces are open and cater to workers who have shifts throughout the day and night, although the exact opening times and times of primary activity (such as meal breaks between shifts) are likely to have varied between food outlets. The menu options provided also varied between outlets. While all the outlets serving one of the two employers offered a consistent menu across locations, the outlets serving the other employer did not. The food outlets were selected and provided by the project delivery partner and, due to contractual obligations with the workplaces and commercial sensitivity, our ability to control for variety or report on specific details related to each food outlet is limited.

There were originally 32 sites allocated to enter the trial, which were randomly allocated into three sequences: 10 in the first sequence (entering in Week 1 of the intervention period) and 11 in both the second and third (entering in Weeks 2 and 3). However, due to staffing issues, three food outlets – one in each sequence – dropped out before entering the trial, leaving 29 food outlets in the final sample.

4.3. Interventions

4.3.1. Free Samples

In the first week of the intervention, we gave out free samples of one of the vegan or vegetarian meals on offer that day in the food outlets (the meals on offer varied by outlet).[1] We sent a fieldworker into the food outlet at lunchtime on the Tuesday, Wednesday and Friday (the days of the week with highest footfall), who handed out the free samples.

The free samples were prepared by the food outlet’s chefs and given out by the fieldworkers in individual disposable containers. Fieldworkers were briefed to position themselves in a location that would likely attract a lot of footfall, such as near the entrance or exit of the food outlet. The promotional worker would approach customers entering the food outlet asking, “Would you like to try the vegan/vegetarian meal of the day?”.

The free samples were advertised on a promotional poster describing the meals on offer at the entrance to the food outlet. They were not advertised beyond the materials in the food outlets as we sought to isolate the impact of the interventions themselves on sales (from any impact of wider advertising).

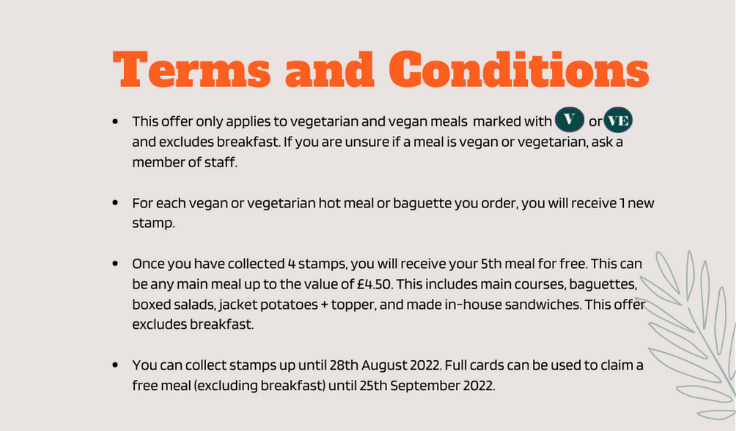

4.3.2. Loyalty card

In each food outlet, loyalty cards were made available for the duration of the intervention period, which could last for two, three, or four weeks depending on when a site entered the intervention (See Figure 1 for details). During these periods, loyalty cards were offered at the till to all paying customers. In addition, during the days when free samples were handed out, if the customer showed interest in the free sample, the promotional worker proceeded to also introduce the loyalty card. Similarly to the free samples, the loyalty cards were not advertised beyond the materials in the food outlets as we sought to isolate the impact of the interventions themselves on sales (from any impact of wider advertising).

Customers received a stamp for each vegan or vegetarian hot meal or baguette they ordered during the lunch and dinner periods. Breakfast was excluded from the trial because the offering was the same each day, so there were no ‘novel’ items to introduce. The food outlet managers also informed us that customers’ food choices at breakfast seemed much more set, suggesting an intervention applied at this meal time would have lower impact.

Once customers had collected four stamps, they could exchange the card for any meal of their choice, vegan/vegetarian or otherwise, until September 25th 2022 (one month after the end of the intervention period). However, the first stamp was given as ‘endowed progress’, so in practice, customers only needed to purchase three qualifying meals to receive a free meal. The design along with the terms and conditions of the loyalty cards can be found in Figure 3 and Figure 4.

4.4. Implementation checks

To maximise compliance with the interventions the research team had a weekly call with the food outlets’ regional managers during the trial to ensure the implementation protocols were followed. This mainly constituted passive monitoring, although we provided corrective steer where the implementation deviated from the agreed process. For example, we provided clarifications about the size of and process for preparing the free sample portions when this was not done correctly in one food outlet, and confirmed with the regional manager that they would amend how these were implemented subsequently.

Additionally, the fieldworkers were asked to share a picture of their workstation and placement in the food outlet, as well as pictures of the samples with the research team. Pictures sent back to the research team were monitored continuously and any discrepancies in the implementation were detected and mitigated where possible and appropriate. For example, one of the food outlets did not follow the correct procedure to distribute the free samples initially and we briefed them to correct this for the next free sample day. However, it was impossible to avoid variation between the food outlets due to differences in layout, staff availability, supply chain issues, and competing priorities.

Fieldworkers were also tasked with completing a short survey at the end of each shift, which consisted of five questions that captured information on the times of their shift, location, number of free samples provided to customers and number of loyalty cards available. This helped ensure that all sites had enough resources to deliver the trial successfully.

4.5. Outcomes

The primary outcome measure in this trial was the number of plant-based options (including main meals, jacket potatoes, made-in-house sandwiches and baguettes, and salads) sold between 11:00am and 02:00am each day. The sales data were drawn from the company’s sales system by the company, which records sales automatically through the till, and shared with us after the trial.

As an alternative measure of the primary outcome, we had the following secondary outcome:

- proportion of plant-based options sold daily between 11:00am and 02:00am

To check the effects on non-plant-based food and that there were no spillover effects on total sales, we also had the following two secondary outcome measures:

-

Number of non-plant-based options sold daily between 11:00am and 02:00am

-

Total number of all options sold daily between 11:00am and 02:00am

Records of sales that occurred outside the specified period (4th July 2022 until 31st July 2022 for baseline period, 1st August 2022 until 28 August 2022 for intervention period, and 29th August 2022 until 2nd October 2022 for post-intervention period), or that did not concern products of interest (i.e., products in the sales data that did not fall under the categories of main meals, jacket potatoes, made-in-house sandwiches and baguettes, and salads), were excluded from the analysis. Since the window of interest for each date was sales that occurred within the period 11:00-02:00, sales which occurred after midnight but before 02:00 were recoded as having occurred on the previous day. Sales which occurred between 02:00-11:00 were excluded entirely as there were negligible sales during the early hours and breakfast was out of scope for the trial (and the exact timing of when breakfast started varied by food outlet). Each product was coded by the delivery partner as either containing meat, vegetarian or vegan.

Sales records were aggregated so that the research team received, for each outlet, the total sales, total income, and the average cost of a product. Additional variables were derived which reflected the total sales, total revenue, and average cost of a product for meals that were vegetarian and for those which were specifically vegan. Further, there were also variables indicating the proportion of sales that were vegetarian, vegan or contained meat. Finally, each date was also coded to indicate whether it occurred after the treatment date, and whether it was in the pre- or post-intervention stage.

4.6. Sample size

Preliminary power calculations were performed to give an indication of the feasibility of the intended designs. These calculations involved simulations – based on sales data from June to August 2022 and assuming the participation of 38 food outlets, which was based on the original number of outlets that expressed an interest in participating, with 10% attrition – where the impact of the intervention was ‘varied’ upon total daily sales. This simulation was conducted using the simr package in R statistical software.

The power calculations assumed the following:

-

The use of a linear mixed effects model with a random intercept per outlet and time fixed effects

-

Three ‘steps’ in which the intervention is introduced, spread evenly across participating food outlets using random allocation; and

-

One month of baseline observations, one ‘treatment’ month in which the intervention is introduced in three steps (as noted above) and one month of ‘follow-up’ observations.

As Figure 5 shows, these indicative simulations suggest that with this design, we would have 80% power to detect an increase of approximately 20% in daily sales of plant-based meal options.

However, when engaging with the food outlets, several outlets indicated that they could no longer participate in the trial because the footfall was too low for it to be worthwhile (potentially due to irregular shift patterns), or they did not have vegetarian or vegan options. Therefore, 32 outlets were randomised (of which 29 eventually participated), which will have increased the minimum detectable effect size, assuming that the power calculation assumptions hold.

4.7. Randomisation

Random assignment to the three sequences occurred at the food outlet level. During the food outlet recruitment process, we collected key information on food outlets– including estimated daily footfall and location. We stratified on the business the outlet serves (the grocery chain and the delivery business), and on average estimated daily footfall to ensure the sequences were similar in terms of key characteristics. This process was executed via stratified random assignment, conducted using R’s randomizr package.

4.8. Blinding

Outlet managers knew that they were taking part in a trial, and in some cases the staff did as well. All staff knew they were taking part in a new programme, although we did not explicitly inform all that it was part of a research project. Customers would have seen the interventions, but were not told that they were being delivered as a part of a trial.

4.9. Statistical Methods

After examining the raw data, we decided to exclude weekends from the analyses because most of the missing values were due to closures on weekends. Excluding weekends reduced the proportion of observations with missing values to 0.86% (10/1160 observations) from 12.25% (199/1624 observations). Given the low number of missing values, we decided not to impute the missing values, to avoid introducing spurious time series correlation.

We used the standard stepped wedge model specification pre-registered in the trial protocol to examine the effects of interventions, as recommended by Hussey and Hughes (2007). It was a linear mixed-effects model that could be written as:

\[Y_{ij} = µ + {\beta_{1}X}_{ij}^{1} + {\beta_{2}X}_{ij}^{2} + \alpha_{i} + \theta_{j} + e_{ij}\]

Where:

-

is the daily volume of plant-based food sales (defined in Section 6.5) at food outlet i (where i =1, 2, …, 29) at time j (where j = 1, 2, …, 56 of baseline and intervention period).

-

is a binary variable indicating whether food outlet i was under free sample and loyalty card interventions at time j; there were three days in the first week of the intervention period when free samples were given out in a food outlet along with the loyalty card.

-

is the estimated treatment effect of free sample plus loyalty card interventions.

-

is a binary variable indicating whether food outlet i was under loyalty card intervention only at time j.

-

is the estimated treatment effect of loyalty card intervention only.

-

is the random effect (intercept) for food outlet i;

-

is a fixed effect for time (each date as a time point); and

-

is the model error term.

To better capture the weekly seasonality of the outcome variables, we also ran an alternative model with day of the week fixed effects instead of the date fixed effects in the main specification. The same models were run for the three secondary outcomes. All statistical analyses were conducted in R Statistical Software. All tests were two-tailed and conducted using a significance level of α = 0.05.

4.10. Process evaluation

A process evaluation was conducted, in order to explore the factors influencing the impact of the interventions (i.e., why the interventions were or were not effective). The qualitative research also explored intervention fidelity (i.e., whether the intervention was delivered as expected) and evaluated the process of implementing the intervention in order to identify learnings and improve future trials.

4.10.1. Managers and staff

Interviews were conducted with food outlet managers and staff to understand the process of delivering the free samples and loyalty card interventions, perceptions of effectiveness, and suggestions for future improvements.

Interviews were conducted with six managers and eight staff members from six outlets. Interviews were conducted in-person, by a member of the research team. Interviews were held at a convenient time—usually just before or after the lunchtime period - and were held at the very end or just after the end of the trial period in each food outlet. All interviews took place, between August 25th, 2022, and September 2nd, 2022. Six outlets (three from each organisation involved in the trial) were selected, based on consideration of travel time for the interviewer, whilst aiming to include a range of outlets in terms of size and geographical location. For each food outlet, the manager in charge of the outlet during the trial period was interviewed. Additionally, one or two customer-facing staff members (staff who served food and/or operated the tills) were selected based on their availability on the day of the researcher visit, and their willingness to take part in the research. See Appendix items 5 (Manager interview) and 6 (staff interview) for the topic guides.

4.10.2. Fieldworkers

Interviews were also conducted with the six fieldworkers who handed out the free samples and loyalty cards in the food outlets selected for manager and staff interviews. The purpose of these interviews was to understand the process of delivering the free samples, customer responses, and get suggestions for future improvements. These interviews were conducted over Zoom, after the trial period on September 26th and 27th 2022. See Appendix item 7 for the topic guide.

4.10.3. Participants (customers in the food outlet)

Two sites in each trial sequence were chosen to receive fieldworker visits to conduct intercept interviews. Intercept interviews are informal interviews conducted on site with research participants, in this case, in the cafeteria environment. The purpose of these interviews was to explore whether participants had noticed the intervention, and understand their experiences and views (for example, whether they had tried the free sample, and whether this had encouraged them to purchase a meal). One site received a visit at the end of the free sample week and one in the last week of the trial (or the week after the trial). These interviews were conducted over two hours during lunchtime. The research team approached customers eating in the restaurant, and asked if they were willing to take part, before asking a short series of questions. A small bag of popcorn was offered as an incentive. Customers were selected based on convenience and willingness to take part in the research.

Interviewers asked customers four questions: whether they had noticed anything different that week at the food outlet, whether they had taken advantage of the promotions (either free samples or loyalty cards, depending on the focus of the interview), whether this had changed the type of food they purchased and whether they had any suggestions to improve the trial.

4.10.4. Analysis approach

Manager, staff and fieldworker interviews were charted using a thematic framework to analyse the delivery and impact of the intervention. The framework included: fidelity (whether the intervention was delivered as expected), acceptability (for implementers and target audience), feasibility (including cost and resource requirements), reach (whether the intended audience participated), perceptions of effectiveness, context (any context influencing delivery or impact) and challenges and learnings. Customer interviews were recorded in a simple excel framework organised according to the four questions.

5. Results

5.1. Participant Flow

There were 29 sites that took part in the trial. Originally 32 sites were allocated to enter the trial, which were recruited in June and July of 2022 and randomly allocated into three sequences: 10 in the first sequence and 11 in both the second and third. However, due to operational priorities, three food outlets – one in each sequence – dropped out before entering the trial. This left 29 food outlets in total, 9 in the first sequence and 10 in both the second and third, which received the interventions. Data for all outlets that entered the trial and received the intervention were analysed. See the trial flowchart, in Figure 6.

5.2. Recruitment

All participating food outlets were recruited through our delivery partner, Compass Group UK & Ireland. and were part of their subsidiary, Eurest.

The delivery partner provided data on all blue-collar sites (that are supplied by their brand that serves distribution centres) they operate across England to assess their eligibility for participation in the trial.

The inclusion criteria for recruitment of sites were based on the following variables:

-

Location: balanced distribution across the country with outlets located in the Greater London area, South-East and Southwest as well as the North of England.

-

Operating hours: outlets that offered lunch and dinner services.

-

Offering: availability of vegan and vegetarian products.

-

Footfall: between 130 and 700 of daily visitors, on average (as estimated by the delivery partner).

-

Data: use of EPOS till system, in order to be able to provide high quality sales data

5.3. Baseline data

During the baseline period (4th–31st July 2022), around 66 meals were sold daily on average in a food outlet, as highlighted in Table 2. Around 19 plant-based meals were sold daily on average in a food outlet, accounting for 30.4% of all options sold daily on average. The numbers were similar across the food outlets in the three sequences, except for the lower mean for number of plant-based options sold daily and proportion of plant-based options sold daily for Sequence 1. This was likely due to Food Outlet 32 in Sequence 1, which had a much lower average number of plant-based options sold daily (4.1) and proportion of plant-based options sold daily (6.1%). See Appendix Table 1 for a food outlet level breakdown of sales data during the baseline period.

5.4. Outcomes and Estimation

We did not find statistically significant effects of the interventions on the volume of plant-based sales. The volume of plant-based sales on days when free samples were handed out was not different from that of the baseline period (coefficient = -0.53, 95% CI [-3.43 – 2.36], p = .718).[2] Nor was the volume different on days with the loyalty card intervention only (coefficient = 0.33, 95% CI [-2.73 – 3.38], p = .834). This was confirmed in an alternative model with day of the week fixed effects instead of date fixed effects, which captured the weekly seasonality better. See Table 3 for results of both models. This lack of difference is highlighted in Figure 7, which tracks the daily volume of plant-ased products sold across the pre-trial period.

Amongst Sequence 1 (4-week intervention period), on average, 14.5 plant-based meals were bought per day during the baseline period (23.1% of total sales) compared to 16.9 plant-based meals per day during the intervention period (25.3% of total sales). In Sequence 2 (3-week intervention period), on average, 20.8 plant-based meals were bought per day during the baseline period (31.5% of total sales) compared to 19.9 plant-based meals per day during the intervention period (30.4% of total sales. In Sequence 3 (2-week intervention period), on average, 21.3 plant-based meals were bought per day during the baseline period (36.2% of total sales) compared to 20.3 plant-based meals per day during the intervention period (38.0% of total sales). For a detailed breakdown of the mean daily volume of sales, see Appendix A Item 1.

We also did not find statistically significant effects of interventions during the intervention period for our secondary outcome, the proportion of sales that were plant-based (coefficient = -0.01, 95% CI [-0.05 – 0.03], p = .573 for days when free samples were handed out; coefficient = -0.02, 95% CI [-0.06 – 0.02], p = .321 for days with the loyalty card intervention only). See Table 4 for full results.

The results for the other two secondary outcomes, sales of non-plant-based sales and total sales, mostly corroborated what we found in the primary outcomes, but with a couple of small differences.

-

The main model (with date fixed effects) showed no differences for non-plant-based sales during the intervention period compared to the baseline period (see Model (1) in Table 5)

-

for days when free samples were handed out (coefficient = -0.57, 95% CI -5.35 – 4.21), p = .814);

-

for days with the loyalty card intervention only (coefficient = 2.25, 95% CI [-2.80 – 7.31], p = .382).

-

-

The main model (with date fixed effects) showed no differences for total sales during the intervention period compared to the baseline period (see Model (1) in Table 6)

-

for days when free samples were handed out (coefficient = -1.09, 95% CI [-6.38 – 4.19], p = .685);

-

for days with the loyalty card intervention only coefficient = 2.61, 95% CI [-2.98 – 8.19], p = .360).

-

-

The alternative model (with day of the week fixed effects) indicated that volume was lower on days with the loyalty card intervention only compared to the baseline period for both non-plant-based sales (coefficient = -2.80, 95% CI [-4.96 – -0.63], p = .011) and total sales (coefficient = -2.56, 95% CI [-4.98 – -0.15], p = .038). It is unlikely that the continuation of loyalty card intervention after the three free sample intervention days led to a decrease of non-plant-based sales, therefore the significant coefficients were likely to be a spurious result due to the models not being able to fully capture the time series patterns.

As we found no effects of the interventions during the intervention period, we did not perform analyses on Hypothesis 2 (examining effects of the interventions after they were withdrawn).

5.5. Process evaluation

5.5.1. Fidelity

Fidelity refers to whether the intervention was delivered as intended.

Implementation checks: The implementation checks revealed some inconsistencies with the trial protocol. During the first week, some food outlets portioned up all estimated samples for the day at the start of the lunch time period. This led to samples getting cold as the lunch break progressed. Other food outlets provided the vegan/vegetarian meal of the day in a large container which customers could take a sample out themselves. Once these issues were identified, all food outlets were asked to portion up samples in batches, to avoid these getting cold whilst also keeping these in a hot food cabinet which promotional workers could have easy access to.

Manager and staff interviews: Managers and staff reported that the intervention was delivered as intended. Loyalty cards were handed out when customers bought a qualifying meal, while free samples were handed out in an appropriate location (for example the entrance to the food outlet, at the start of the queue). Briefing prior to the trial was generally felt to have been extensive and clear.

The interviews revealed a few inconsistencies with the protocol. In one site, a member of staff mistakenly thought the free meal had to also be vegetarian, and was communicating this to customers. This occurred because that staff member missed a morning briefing due to shift patterns. Although all staff were briefed in daily morning meetings, these could be missed by a few workers due to changing shift patterns across the day.

Fieldworkers: Fieldworkers reported delivering the intervention as described in the protocol and briefing documents. Managers placed them at an appropriate place in the food outlet, usually at the start of the queue and actively attempted to engage with customers as they passed through.

When customers stopped to take a free sample, fieldworkers tended to give them more information about the interventions, including both the free samples and loyalty card, for example informing them that the samples were on sale that day and that the loyalty card allowed them to redeem a free meat or vegetarian meal. They also told customers that the samples were part of a promotion for sustainable or vegetarian/plant-based food. However, this was not done consistently, with some actively leading with this information, and others only elaborating when asked further questions.

One deviation from the protocol involved a fieldworker going around the cafeteria offering samples to diners who were eating their own homemade food. They chose to do so as the numbers of diners in the food outlet was low and there was samples leftover, and with the intention of widening the impact of the intervention to those not typically choosing to purchase food in the food outlet.

The food outlet staff and fieldworkers worked effectively to communicate when new samples were needed and to prepare these to ensure there were always samples available.

5.5.2. Reach

Reach refers to whether the intended audience participated.

Managers and Staff: Free samples were always visible and clearly displayed, and were generally accepted by customers. There was a perception that the loyalty cards were not well used, and more likely to be taken up by vegetarian customers. Interviewees said reach would have benefitted from better advertising in food outlets, for example posters or flyers to advertise the loyalty cards.

There was a general impression that food outlets were less busy during lunchtime than at other times (specifically breakfast and dinner), and that implementing the trial at busier shifts could have improved reach. Furthermore, workers often have a short lunch break and there was a perception that this is maximised by making habitual decisions. Staff also felt this limited customer willingness to engage in conversation with staff, which meant staff were unable to explain the intervention to them.

Fieldworkers: Fieldworkers did not think that all customers passing through the food outlet took a sample and/or loyalty card. They often reported finding it difficult to encourage customers to take the free samples and occasionally noticed that customers did not actually eat the free sample.

One challenge was that many of the customers did not understand English and therefore fieldworkers struggled to explain the trial and encourage them to take the sample and loyalty card.

Generally, fieldworkers also felt that customers were reluctant to try the free samples, due to some hesitancy around trying new things in general. Diners were also rushed in their engagement with the intervention, as they wanted to enjoy their limited break. It is possible that those who took the time to speak to the fieldworkers and understand more about the intervention were more likely to engage. Fieldworkers found that stressing that the sample was free along with a personable attitude and gentle persistence could be effective at encouraging people to take the sample.

The food outlets were also not particularly busy at lunchtimes, with many bringing their own lunch or eating in other areas within the building. Fieldworkers felt the intervention may have reached more people if implemented at busier shifts such as breakfast and dinner, or if there were more posters and communications around the food outlet and building to advertise the trials.

Customers: Some customers had no spontaneous awareness of anything new happening in the food outlet, but recalled seeing the fieldworker when prompted. However, not all were aware that they were handing out free samples. Others spontaneously mentioned seeing the fieldworker handing out free samples, although few referred to these being plant-based.

Customers had often not tried the free samples. Reasons for not doing so included: bringing their own food from home, already knowing what they wanted to buy, always eating the same things, not knowing what the sample was, or preferring to eat meat.

5.5.3. Acceptability

Acceptability refers to whether the intervention was acceptable to implementers and the target audience.

Managers and Staff: The set-up of free samples was easy to implement and did not disrupt any of the outlet staff activities. The loyalty card also did not significantly impact the staff day-to-day. Overall, managers and staff did not raise any negative perceptions of implementing the trial.

Fieldworkers: In general, fieldworkers felt that customers who did take the samples did enjoy them and that the interventions did not disrupt their enjoyment or experience of using the food outlet. They also did not feel their presence disrupted day-to-day running of the food outlet, and that they were welcomed by the staff and manager.

Customers: For those who had taken samples, most said the food was good, with only a few saying the food tasted bad or was left out too long. Customers did not discuss any negative impact on the dining experience. One person mentioned they would have preferred the samples to be left out without the need to talk to the fieldworker.

5.5.4. Feasibility

Feasibility refers to whether the intervention is feasible when considering factors including costs and resource requirements.

Managers and Staff: The free samples intervention did not require significant extra resource in terms of staff time. Since the vegetarian meal from which samples were taken would already be prepared by outlet staff, the only additional activity was portion sampling, which did not require much of their resources.

However, the presence of a fieldworker offering the samples was reported as fundamental to encourage customers to try them out, and food outlets would not have the capacity to fulfil this role internally. Therefore, it may not be logistically feasible to continue to offer the free samples on a regular basis, without the additional resource.

The loyalty card intervention also did not require extra resource, and staff did not think that the activities of handing out, stamping or explaining the loyalty card took them significant time. However, the process of setting up the till process to redeem free meals was complicated in some food outlets, requiring additional time from the manager to assist the staff. If loyalty cards are to be sustainable, it is important that the process of redeeming the free meal is streamlined.

Fieldworkers: Fieldworkers agreed that having an individual present who was experienced in customer engagement, was an important factor in the trial. Without this role, they thought it unlikely that customers would take up the samples.

5.5.5. Effectiveness

This section seeks to understand the perceived effectiveness of the intervention by implementers and the target audience.

Managers and Staff: In terms of staff and manager perceptions, there was no consensus on whether sales of vegetarian and vegan products had increased during the intervention period. Some said they thought the trial had increased sales, whilst others perceived little change to customer behaviour. Those that perceived no change felt this could be due to the low acceptability and reach of the intervention (for example, consumers being hesitant to try new things, particularly plant-based foods, and particularly in the rushed habitual cafeteria environment). There is some risk of social desirability bias influencing answers, in that interviewees may have felt the pressure to report the trial as a success. However, many openly expressed their view that we would find a null effect, suggesting this did not bias answers in all cases.

In the interviews, the free samples were thought to be more effective than loyalty cards, since those customers who tried and liked them would be more likely to buy the vegetarian meal afterwards. Loyalty cards were, according to managers and staff, usually taken up by already vegetarian customers and not many were redeemed.

Fieldworkers: Overall, fieldworkers did not feel the intervention was effective at changing the meals purchased.

They thought the type of people eating in the food outlet had hard to shift perceptions, particularly around plant-based foods, and were resistant to change, habitually eating the same things each week, and not thinking about making a decision when they come in for lunch. They did not think the intervention would be successful in disrupting this habit or encouraging them to reconsider meal choices.

Fieldworkers also felt that consumers found price and health to be important factors in deciding what someone purchased, and that this could shift choices away from the plant-based option. For example, one fieldworker mentioned a female employee enjoying the vegetarian sample, but choosing to buy the meat instead due to the lower calorie content and price.

Customers: Only a small number of customers said that the sample had influenced their food choice. Some customers said the samples were helpful in encouraging them to try new foods, but whether or not they then purchased the main would depend on the price, the other options available, and their mood that day. Customers who did not change their choice stated reasons such as: preferring other options, not wanting vegetarian food or preferring to eat the same things. Many also regularly brought their own lunch rather than purchasing it from the food outlet.

Customers said that people eating in the cafeterias (including themselves) were ‘stuck in their ways’, knowing what they wanted, tending to eat the same things regularly and being resistant to trying new things. There was also distrust of unfamiliar foods, for example not being sure what the ingredients would be (for example, distrust of plant-based goulash, because it was unfamiliar, but higher acceptability of the plant-based burrito, because it was familiar). Some said there was nothing that would encourage them to eat vegetarian food.

Suggestions for improving the effectiveness of the free samples included: offering more culturally relevant dishes for the customers working in that location, making the samples more visible (for example, using a larger sign to advertise or placing them in a more salient location), making sure the samples look and smell appealing, emphasising any health claims as well as the vegetarian nature of the food and its environmental sustainability and providing them on busier shifts such as breakfast.

Suggestions for encouraging plant-based food consumption more generally included: increasing the options available and making them more familiar (for example using meat alternatives), ensuring foods are tasty and appealing, and ‘hearty’ and filling, and reducing the price of vegetarian food.

5.5.6. Context

This section seeks to understand any contextual factors influencing the delivery or impact of the intervention.

Fieldworkers: The experience and personality of the fieldworker could potentially impact the extent to which customers engaged with the free samples and loyalty card. Several of the fieldworkers interviewed had worked in similar roles, for example in supermarkets or festivals, and had developed an understanding of what worked well to engage people. They also discussed feeling their personality, for example being naturally chatty and agreeable, was important in establishing rapport and engaging customers.

Fieldworkers commented on the appearance of the sample and the influence this could have on engagement. Most felt the samples were well presented, but one had intervened to improve the size and appearance of the sample during their shift.

One mentioned that the staff seemed unprepared, for example the chef being unsure how to prepare one of the meals. It is therefore possible there was some deviation in the quality of the samples available.

Fieldworkers mentioned that often the people coming through were the same each day. It is possible therefore that the same people were taking the sample each day, perhaps limiting the reach.

Customers: Outside of the trial, some of the food outlets ran regular promotional days, such as ‘wellbeing Wednesdays’ or more occasional promotions, for example providing tasters when new menu items were added. In the food outlet where free tasters had been run previously, customers may have been more engaged and willing to take up the samples.

Customers of the food outlets were described as primarily men, although some food outlets also served office workers of whom the majority was female. It is possible this could influence the type of meals sold.

6. Discussion

Free samples and loyalty cards did not increase purchases of plant-based meals in this study. We did not detect any significant differences in the volume of plant-based sales during the intervention period compared to the baseline period on the free sample days (coefficient = -0.53, 95% CI [-3.43 – 2.36], p = .718) or on days with the loyalty card intervention only (coefficient = 0.33, 95% CI [-2.73 – 3.38], p = .834).

The lack of effect of the free samples is consistent with two other studies that investigate free samples of wine (Nin Ho & Patrick Gallagher, 2005) and chocolate (Lammers, 1991; Nin Ho & Patrick Gallagher, 2005), which also found that the samples did not increase purchases of the item being sampled. In contrast, studies in Malaysia and Brazil found that consumers reported that free samples would make them more likely to trial a new product in a supermarket. However, these studies might not be representative due to possible cultural differences with High Income Countries, and the outcome measures were self-reported, rather than observed behaviour and may therefore not be as robust (Oly Ndubisi & Tung Moi, 2006; Vigna & Mainardes, 2019).

Our process evaluation suggests that customers in the food outlets who tried the meals generally liked them. However, many customers either did not try the meal, or tried it but chose not to purchase it because they preferred to eat their usual meal or had brought their own lunch. Although we addressed the barrier of being worried about the taste amongst those who tried samples, customers still preferred to eat their regular meal. This first factor—that despite liking a sample customers prefer their usual purchase—might apply more widely to sampling in other contexts. This goes back to the point that habit and taste are highly important in food choice (Osman & Jenkins, 2021), and habits can be difficult to break.

It is possible that the free sample intervention would have been more effective with a different food or a different operationalisation. The food that was offered was limited by what the food outlets were making and what they decided could be portioned up into samples (we had no influence on the meals offered). The food might have been culturally unfamiliar (noting that in the process evaluation we found that many customers were not native English speakers). In the process evaluation, customers also mentioned calorie content and price as reasons for preferring other meals. Potentially, other meals would have been more successful in a free sample intervention. Some food outlets portioned up all estimated samples for the day at the start of lunchtime, leading to samples getting cold as the lunch break progressed. We could also have more directly connected the samples to the meals customers were about to purchase. It might have been more effective if we had given an explicit prompt to consumers to buy the meal afterwards, for example by saying “Try this for free. If you like it, why not buy it as a main meal today?” in the poster for the free samples or when the fieldworker promoted the free samples. In support of this, a promotion of low-fat products in a supermarket that used a combination of samples, price discount, and prompting was successful at increasing the purchase of low-fat frozen desserts (Paine-Andrews et al., 1996). However, engaging fieldworkers to direct people to make a purchase after sampling is not scalable.

More likely, free samples simply do not have an effect on purchasing. We could never expect them to affect everyone because preferences over flavours vary a lot between individuals, and it is difficult to make generalisations about what tastes people will enjoy and want to re-experience (Sendra-Nadal & Carbonell-Barrachina, 2017). Further, other factors may be more important than taste in terms of inducing a sale immediately following sampling (Nin Ho & Patrick Gallagher, 2005). However, free samples may serve other purposes for marketeers, for instance getting people into the store and increasing purchases in general. For example, Lammers et al (1991) found that in-store free samples in a chocolate shop increased sales of other varieties, but not the one that was given out as a sample. Samples may also be used to increase product and brand recognition.

The lack of an effect of loyalty cards is surprising, given the known effectiveness of price discounts, including when combined with free samples (Bawa & Shoemaker, 2004). However, the results of our intercept interviews and fieldworker visits suggest that customers were not aware of the loyalty cards, which were not widely utilised. If they did not know about the cards, then adding the loyalty cards into the food outlet environment could not have impacted on their incentives (and therefore their reflective decision-making). It is also possible that the cards would have needed to run for a longer period in order to be effective. The rapidly changing situation post-covid made it difficult to gather reliable data in the design stage to estimate how often people bought food from the outlets and what meals they were buying. Potentially a straightforward price discount would have been more effective. However, we note that, in many cases, there were cheaper meals available than the plant-based option, even considering the indirect discount offered by the loyalty card, which might have limited the impact of the intervention (particularly on price-sensitive customers, who might have been more likely to respond to a price-based intervention otherwise).

Regarding free samples, future research might consider intermediate stages in the journey between being offered a sample and purchasing it. Do free samples increase consumers’ awareness of these options? Do consumers evaluate the samples favourably? Do they perceive the product being sampled to offer good value for money? The effectiveness of free samples depends on all the stages in the journey. Therefore, answering these questions may help determine when and why offering free samples increases subsequent purchases of products. For loyalty cards, there are questions of whether they increase brand or outlet loyalty; and whether they can assist with the introduction of new products or whether their main purpose is to retain current customers or current purchasers of products.

6.1. Limitations

Several features of the trial may have impacted on our ability to generate and detect an effect.

The sample size was relatively small as it was limited by the availability of food outlets that were operated by the delivery partner, that used a reliable method to capture sales data, and that were willing to participate in this trial. The small sample size means that we were limited in our ability to detect an effect and that, if there was a small effect, we might not have detected this. Moreover, three out of the 32 food outlets had to drop out during the trial, further reducing our statistical power. In the participating food outlets the breakfast and dinner shifts are generally busier than the lunch shift. While we had determined the eligibility of food outlets based partially on footfall, and made an effort to ensure sufficient sales per food outlet, there was no reliable data available at the point of randomisation on footfall during each specific mealtime and the number of transactions over lunch was lower than anticipated.

The food outlets included in this trial were all based in large distribution centres (central storage and sorting locations from which large organisations distribute their products) and were operated by just two large national employers. It is possible that features of the setting or the workforce influenced the impact of the interventions, and that results of these types of interventions might differ in other settings. Potentially other target groups would be more responsive. We chose to target lower socioeconomic status (SES) groups, which have both a lower level of eating plant-based foods and may be less likely to change their diet than higher SES groups (E. J. Lea et al., 2006; Pohjolainen et al., 2015).

Features of the workforce and of their shift patterns may have impacted the effect of our interventions. For example, the process evaluation found that many employees (the food outlet customers) had a relatively short lunch break and sought to minimise time spent purchasing lunch – if they had not brought lunch from home. Several of the customers we interviewed highlighted that their lunch meal decision making was driven by habits and familiarity, and that this impacted on their willingness to engage with the interventions and to try an unfamiliar meal option. It is possible that in other settings where purchases are not quite so habitual, such as a restaurant the customer has not been to before, interventions that seek to encourage individuals to try something new might have a greater impact. The brevity of lunchbreaks also limited customers’ willingness to engage in conversation with the food outlet staff, which reduced staff’s ability to advertise the samples and loyalty cards.

Another feature of the specific settings in which the interventions were delivered is that, according to the fieldworkers, a significant proportion of the workforce, i.e. potential food outlet customers, spoke English as an additional language and had limited English proficiency. This could have reduced awareness of the interventions, as the free samples were advertised with English-language posters and the loyalty cards contained their terms and conditions in English.

Staff and fieldworkers alike highlighted that the fieldworkers played a significant part in encouraging take up of the free samples, in particular. The food outlet staff would not normally have enough time to actively advertise free samples in the way fieldworkers could, and it is possible that a wider rollout in which there is only passive distribution of free samples then there might be less uptake of the samples (which we hypothesise would further reduce any potential small effect they may have had).

6.2. Conclusion

We tested the effect of handing out free samples and introducing loyalty cards on purchases of plant-based meals in a blue-collar workplace food environment. Neither intervention was effective. Workers who tried the free samples seemed to like them, but there was no evidence of an increase in purchases. The loyalty cards were not utilised very often, it seems that many customers were not aware of them. This contributes to a small literature that suggests that free samples do not increase purchases of the sampled product, at least not without other supporting interventions.

Registration

Title: Exploring the impact of giving free food samples and loyalty cards on sustainable food choices: A stepped wedge trial in workplace food outlets.

Registration DOI: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/B3Y5C

Protocol

The protocol can be accessed in the Study design section if the pre-registration at https://osf.io/b3y5c

Funding

The study was funded by the Food Standards Agency.

Research ethics review

The study was approved by LSE ethics committee (Ref: 65670).

The free samples and the free meals from redeemed loyalty cards were funded by the FSA, not the delivery partner.

The loyalty card scheme was also in operation on these days.

_a_.png)

_a_.png)