1. Executive Summary

Cell-cultivated products are foods made without slaughter or traditional farming. For example, cells from animals are grown in a controlled setting and then used to create the final product. In October 2024, the Food Standards Agency (FSA) announced it had received £1.6 million from the Government’s Engineering Biology Sandbox Fund (EBSF) to run a programme designed to make sure cell-cultivated products (CCPs) are safe for consumers before they are approved for sale. The programme is set to launch in March 2025 and updates will be published on food.gov.uk. This rapid evidence review was commissioned to consolidate the current evidence on consumer views of CCPs.

This review updates three existing reviews on consumer responses to cell-cultivated products (FSA 2020; FSANZ 2023b; University of Adelaide, 2023). Searches of electronic databases and hand-searching were used to identify 12 empirical studies to add to the three existing reviews. Most of the 12 additional studies were new (published between 2023-2024), except for two which were published in 2015 and 2018. The rapid evidence review includes peer-reviewed articles published in academic journals as well as grey literature.

Most studies examined consumer responses to cell-cultivated meat and/or seafood. Only one UK study examined consumer responses to cell-cultivated plants, and only one international study examined consumer responses to cell-cultivated dairy. Limited evidence was available comparing consumer views between different religious groups or vegetarians/vegans vs. omnivores.

The key findings are summarised below (in more detail than the Abstract), grouped by research question. All findings are based on UK evidence, except where otherwise stated.

How willing are consumers to consume cell-cultivated products?

-

A minority (16-41%) of people are willing to consume cell-cultivated meat in the UK.

-

Studies reporting a higher percentage of people willing to consume cell-cultivated meat tended to use the term ‘cultivated’ rather than ‘lab-grown’, provided participants with a description of the product emphasising its benefits, and/or surveyed participants in more recent years.

-

Although there are some differences between different demographic groups, the most important predictors of consumption intentions are believing that there are any benefits of cell-cultivated meat and feeling confident in regulation.

-

Willingness to consume cell-cultivated meat in the UK has not significantly changed within the past two years (2022-2024), but appears to have increased over longer time periods.

-

Limited evidence suggests that people in the UK may be more willing to consume cell-cultivated plants than cell-cultivated meat.

What are consumers’ attitudes towards cell-cultivated products?

-

Over half of people (59%) think cell-cultivated meat could offer benefits compared to traditional meat products, particularly for animal welfare, the environment and global food availability.

-

However, most people (85%) also have concerns about cell-cultivated meat, particularly about it being safe to eat, sounding unnatural and the impact on farmers.

-

International evidence suggests that consumers perceive cell-cultivated dairy to be just as unsafe as cell-cultivated meat.

-

Perceived risks/concerns about cell-cultivated meat are more prevalent than perceived benefits.

-

People are more likely to have positive attitudes towards cell-cultivated meat if they are male, younger, university educated, have a higher income, live in urban locations, have previously heard of the product, or are from England/Wales (rather than Northern Ireland).

-

Peoples’ perceptions of the healthiness/nutritional value of cell-cultivated meat relative to conventional meat appear to be highly malleable depending on the type of information received and product categories compared.

-

Most people are unwilling to pay more for cell-cultivated meat than farmed meat. However, international evidence suggests that people may be willing to pay more for cell-cultivated seafood compared to farmed seafood, although not compared to wild-caught seafood.

-

Willingness to pay for cell-cultivated meat and seafood is generally higher when people are primed with positive information about the product.

How does the terminology applied to cell-cultivated products influence consumer perceptions and understanding?

-

No terminology achieves 100% consumer understanding of the true nature of cell-cultivated meat or seafood (i.e., that the product is neither wild-caught nor farm-raised).

-

Terms that incorporate the word ‘cell’ (e.g., ‘cell-cultivated’, ‘cell-cultured’ and ‘cell-based’) enable most consumers to correctly identify that the product is neither wild-caught nor farm-raised.

-

However, terms that incorporate the word ‘cell’ are less appealing to consumers than the terms ‘cultured’ or ‘cultivated’.

-

Terms containing the word ‘cell’ are also perceived as more likely to be GM and less natural compared to the terms ‘cultured’ or ‘cultivated’.

-

Consumers generally have a poor understanding of the terms ‘cultured’ and ‘cultivated’, and the higher consumer appeal of these terms may disappear once consumers become more familiar with cell-cultivated products.

-

While consumers are most familiar with the term ‘lab-grown’ and generally understand that it does not mean wild-caught nor farm-raised, it causes consumers to perceive the product as being less safe compared to other terms.

-

The term ‘artificial’ causes consumers to incorrectly perceive the product as plant-based.

-

Consumer understanding of the allergen potential of cell-cultivated meat and seafood is low for all terms, particularly ‘cell-based.’

What do consumers think about FSA involvement, regulation and labelling of cell-cultivated products?

-

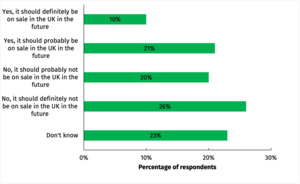

People are generally unsure about whether regulation will prevent the sale of unsafe cell-cultivated meat, and most people either think that cell-cultivated meat should not be on sale in the UK in future (46%) or are unsure (23%).

-

Nevertheless, people expect these products to be regulated and clearly labelled.

-

People are more likely to have confidence in regulation if they are male, younger, or have previously heard of the term ‘lab-grown meat’.

-

FSA approval of cell-cultivated meat is perceived as moderately to very important, and as slightly more important than other on-label claims such as ‘slaughter-free’, ‘carbon-neutral’, ‘produced without antibiotics’, and ‘non-GMO’.

-

Jewish consumers perceive ‘kosher’ labels on cell-cultivated meat to be important, however this is less important than the product being approved by the FSA and produced without antibiotics. Conversely, Muslim consumers perceive ‘halal’ labels as the most important, even more so than being FSA approved and produced without antibiotics.

-

International evidence suggests that people don’t have a strong opinion on whether cell-cultivated meat/seafood should be sold in the same section of the supermarket as conventional meat/seafood.

2. Introduction

Cell-cultivated products are foods made without slaughter or traditional farming. For example, cells from animals are grown in a controlled setting and then used to create the final product. In October 2024, the Food Standards Agency (FSA) announced it had received £1.6 million from the Government’s Engineering Biology Sandbox Fund (EBSF) to run a programme designed to make sure cell-cultivated products (CCPs) are safe for consumers before they are approved for sale. The programme is set to launch in March 2025 and updates will be published on food.gov.uk. This rapid evidence review was commissioned to consolidate the current evidence on consumer views of CCPs.

The types of cell-cultivated products that were in scope for the rapid evidence review were cell-cultivated meat, seafood, dairy and plants. There are currently many terminologies used to refer to cell-cultivated products (e.g., ‘cell-cultivated’, ‘cell-cultured’, ‘cell-based’, ‘lab-grown’, ‘cultured’, ‘cultivated’, ‘clean’, ‘artificial’, ‘slaughter-free’, ‘in vitro’). Throughout this report, the term ‘cell-cultivated’ is used.

The rapid evidence review investigated the following research questions:

-

How willing are consumers to consume cell cultivated products?

a. Which demographic groups are more/less willing to consume cell-cultivated products?

b. Has willingness to consume cell-cultivated products changed between 2021 and 2023?

-

What are consumers’ attitudes towards cell-cultivated products?

a. What do consumers see as the benefits of cell-cultivated products and what are their concerns?

b. What are consumers’ attitudes towards cell-cultivated products in relation to sustainability, shelf-life, cost and healthiness?

c. How do attitudes differ by demographics? What are the views of religious communities, for example, views on if these products are considered kosher/ halal, or vegetarian/ vegan

-

How does the terminology applied to cell-cultivated products, such as ‘lab-grown’, or ‘cultured meat’, influence consumer perceptions and understanding?

-

What do consumers think about regulation and labelling of cell-cultivated products?

-

What do consumers think government and the FSA’s role should be in relation to these products?

3. Methods

The rapid evidence review updated three existing reviews on this topic that had previously been undertaken by the FSA (2020), Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ, 2023b) and the University of Adelaide (2023). It includes peer-reviewed articles published in academic journals, as well as grey literature, such as government reports and non-government organisation reports.

The rapid evidence review also includes analysis of FSA’s most recent survey data on this topic, including:

-

Waves 4 and 8 of the Food and You 2 survey (FSA, 2022, FSA, 2024b)

-

The October 2024 wave of the Consumer Insights Tracker (FSA, 2024a)

The Food and You 2 survey measures consumers’ self-reported knowledge, attitudes and behaviour relating to food safety and other food-related behaviours, and is conducted approximately every 6 months. The Food and You 2 survey utilises a push-to-web methodology (online survey with a postal option) and includes a nationally representative sample of approximately 6,000 adults across England, Wales, Northern Ireland and (in wave 8) Scotland.

Conversely, the Consumer Insights Tracker (CIT) is conducted monthly to provide more quick and frequent insights. The CIT is an online survey and includes a nationally representative sample of approximately 2,000 adults across England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Although the Food and You 2 survey generally has a more robust methodology than the CIT, only online participants were asked the survey questions about cell-cultivated meat in waves 4 and 8 of the Food and You 2 survey.

More information about these surveys is available on the FSA website, as linked above.

3.1. Evidence review

3.1.1. Evidence review strategy

Literature on cell-cultivated meat, seafood and dairy was searched from March 2023 onwards, given that the most recent review on this topic (University of Adelaide, 2023) was completed on this date. However, literature on cell-cultivated plants was searched from 2014 to include studies within the last 10 years, given that none of the existing reviews to date had included cell-cultivated plants.

Both UK and (English-speaking) international studies were included in the review. However, given the high number of UK studies examining consumers’ willingness to consume cell-cultivated products, new international studies were excluded from the review if they only examined this research question. This was to keep the review manageable, and was also informed by evidence suggesting cross-country differences in consumption intentions (FSA, 2020).

Literature was identified by:

-

Searching three online databases for peer-reviewed studies

-

Searching Google Scholar (first 100 hits)

-

Examining a list of references provided by Food Standards Scotland

In addition, one new study was sent via email from the Good Food Institute (GFI, unpublished). More detail on the literature search strategy and research review process are available in Appendix A (Section 8.1).

3.1.2. Study quality assessment

The quality of each individual study was not assessed using a standardised quality assessment tool (or checklist), given the anticipated high number of included studies and the need to produce a timely evidence synthesis. Rather, the general strengths and limitations of each study were considered in the narrative when forming overall conclusions. This is a commonly used approach when conducting rapid evidence reviews (Tricco et al., 2015).

3.2. Analysis of FSA survey data

Data from the FSA’s Food and You 2 and CIT surveys were analysed using R statistical software. Descriptive statistics (percentages) were calculated to give a general overview of participants’ responses, and binomial logistic regression was used to determine whether there were any significant differences between participants’ responses based on various demographic factors. All analyses were based on weighted data.

More detail on the data analysis methods is available in Appendix A (Section 8.2)

3.3. Evidence synthesis

Evidence was narratively synthesised from the three existing reviews (FSA, 2020; FSANZ, 2023b; University of Adelaide, 2023), new empirical research and analysis of the FSA’s survey data. The findings were grouped thematically by research question.

When forming overall conclusions, more weight was given to higher quality studies. Where available, more weight was also given to UK studies, provided they were of sufficient quality. The general strengths and limitations of each study were considered and are narratively described throughout the report (see section 4.1.2 above).

4. Results

4.1. Overview of study characteristics

Three reviews and 12 additional empirical studies (not included in the reviews) were eligible for inclusion. Six of the empirical studies were grey literature (i.e., research produced by government and non-government agencies), and six were peer-reviewed journal articles published in academic journals. All three reviews included a mix of grey literature and peer-reviewed journal articles. The 12 empirical studies were new (published between 2023 and 2024), except for two which were published in 2015 and 2018 (Circus & Robison, 2018; Government Office for Science, 2015).

Seven of the empirical studies were based in the UK, whereas five were based in the USA. The three reviews included a mix of UK and international evidence; where appropriate, more weight is given to the UK evidence in the current report.

Most studies examined consumer responses to cell-cultivated meat and/or seafood. Only one (UK) study examined consumer responses to cell-cultivated plants (cell-cultivated cacao; Herziger, 2024), and only one (Australian/New Zealand) study examined consumer responses to cell-cultivated dairy (FSANZ, 2023a).

4.2. How willing are consumers to consume cell-cultivated products?

The University of Adelaide (2023) concluded that peoples’ willingness to consume cell-cultivated meat was highly varied across different studies, likely due to differences in research methodologies, including the different countries examined. The review by FSA (2020) further suggested that consumption intentions vary across different countries, with people in the UK being less willing to consume cell-cultivated meat than people in the USA.

Due to the high volume of UK studies that examined this research question (n = 9), and evidence suggesting cross-country differences, this section of the current review focuses on UK studies with only brief reference to the international literature. Most of the available evidence was on cell-cultivated meat. Only one study examined cell-cultivated plants (cell-cultivated cacao), and no studies examined cell-cultivated dairy or seafood.

4.2.1. Overview of key findings

-

A minority (16-41%) of people are willing to consume cell-cultivated meat in the UK.

-

Studies reporting a higher percentage of people willing to consume cell-cultivated meat tended to use the term ‘cultivated’ rather than ‘lab-grown’, provided participants with a description of the product emphasising its benefits, and/or surveyed participants in more recent years.

-

Willingness to consume cell-cultivated meat is lower in the UK than in the USA.

-

People in the UK are more likely to be willing to consume cell-cultivated meat if they are:

-

Male

-

Younger

-

From England or Wales (rather than Northern Ireland)

-

University educated

-

Have a high meat attachment (rather than a low meat attachment)

-

Are familiar with cell-cultivated meat terms

-

Have no concerns about cell-cultivated meat

-

Believe there are any benefits of cell-cultivated meat

-

Are confident that regulation will prevent the unsafe sale of cell-cultivated meat

-

-

The most important predictors of consumption intentions in the UK are believing that there are any benefits of cell-cultivated meat and feeling confident in regulation.

-

International evidence indicates that people who regularly consume plant-based meat (at least once a month) or are more politically liberal are also more willing to consume cell-cultivated meat.

-

It is unclear whether vegetarians or vegans are more or less likely to be willing to consume cell-cultivated products than omnivores, due to low sample sizes of vegetarians/vegans across all surveys.

-

Willingness to consume cell-cultivated meat in the UK has not significantly changed within the past two years (2022-2024).

-

However, willingness to consume cell-cultivated meat in the UK may have increased over longer time periods (the past seven years or so).

-

Limited evidence suggests that people in the UK may be more willing to consume cell-cultivated plants than cell-cultivated meat.

A more detailed description of the evidence is provided below, grouped by research question: percentage of consumers willing to consume cell-cultivated products; who is more willing to consume cell-cultivated products; has willingness to consume cell-cultivated products changed between 2021 and 2023.

4.2.2. Percentage of consumers willing to consume cell-cultivated products

Most of the nine UK studies reported the percentage of participants who were willing to consume cell-cultivated products (as opposed to group means from Likert scale ratings, for example). Two studies were cited in the University of Adelaide’s (2023) review (Szejda et al., 2021; Verbeke et al., 2015), two were cited in FSA’s (2020) review (Surveygoo, 2018; The Grocer, 2017), and five were new empirical studies not cited in either review (Circus and Robison, 2018; FSA, 2021, FSA, 2024b, FSA, 2024a; Herziger, 2024).

The review by the University of Adelaide (2023) suggests that people may be more willing to try cell-cultivated meat (a one-time behaviour) than incorporate it into their diet (a repeated behaviour). This conclusion was based on all studies included in the University’s review, not just the UK studies. Although some of the UK studies measured willingness to try and others measured willingness to include in the diet, differences in other methodological features across the studies makes direct comparisons between the different measures challenging. This section therefore makes conclusions about consumers’ willingness to consume cell-cultivated meat more generally.

Table 1 provides an overview of the methods and findings of each UK study to demonstrate their methodological differences and thus where they are not comparable.

Overall, the percentage of participants who were willing to consume cell-cultivated meat varied from 16-41% across studies[1]. Studies reporting a higher percentage of those willing to consume tended to use the term ‘cultivated’ rather than ‘lab-grown’, provided participants with a description of the product emphasising its benefits, and/or surveyed participants in more recent years. The remainder of this section provides a more detailed discussion of these pattern of results based on methodological similarities where possible.

As shown in Table 1, three recent studies that provided participants with no description or a neutral description of cell-cultivated meat and used the term ‘lab-grown meat’ found that approximately one quarter to one third of participants (26-34%) were willing to consume cell-cultivated meat (FSA, 2021, FSA, 2024b, FSA, 2024a). The most prevalent response within each of these studies was that participants were unwilling to consume the product (43-61% unwilling; 11-23% undecided). Two additional studies did not report the percentage of participants who selected each response (Herziger, 2024; Verbeke et al., 2015). However, generally consistent with the previous three studies, willingness to consume the product was not a prevalent response; Verbeke et al. (2015) reported that most were unwilling to try it, and Herziger found that people were generally neutral or unsure (i.e., selected the midpoint of the rating scale).

The study by Herziger (2024) also examined cell-cultivated cacao. In contrast to the ratings for cell-cultivated meat, participants’ mean rating for cell-cultivated cacao was slightly but statistically significantly above the midpoint of the scale, indicating that participants may be more willing to try cell-cultivated plants than cell-cultivated meat. However, the exact percentage of participants willing to try cell-cultivated cacao is unknown (not reported by the authors). The study is also limited such that it only examined one type of plant.

Two additional studies reported a much lower percentage of participants (16-18%) willing to try cell-cultivated meat (Surveygoo, 2018; The Grocer, 2017). These were the oldest studies that reported percentages (published in 2017 and 2018), where consumer awareness of the product may have been much lower than in more recent studies (see Section 5.2.3 for further discussion of the effect of product familiarity on consumption intentions). It is also possible that other methodological differences in The Grocer (2017) produced a lower level of willingness to try the product compared to other studies; methodological information for The Grocer (2017) was largely missing (see Table 1).

One further study (Circus & Robison, 2018) reported a higher percentage of participants willing to consume cell-cultivated meat (41%). It is unclear whether participants in this study were provided with a description of cell-cultivated meat prior to being asked about their consumption intentions.

The study that reported the highest percentage of participants willing to consume cell-cultivated meat (over 70%; Szejda et al., 2021) used the term ‘cultivated’ (rather than ‘lab-grown’; see Section 5.4 for further discussion of the influence of terminology on consumer appeal) and provided participants with a description of cell-cultivated meat that emphasised its benefits. While previous research has shown that emphasising the benefits of cell-cultivated meat may increase consumers’ consumption intentions (University of Adelaide, 2023), the biased response categories that were used in Szejda et al. (2021) likely also contributed to this high percentage. That is, four out of the five response options in Szejda et al.'s (2021) study generally indicated a willingness to consume (see Table 1). Confidence in this finding is therefore low[2].

4.2.3. Who is more likely to be willing to consume cell-cultivated meat?

Seven of the previously described UK studies also examined whether willingness to consume cell-cultivated meat significantly differed across different demographic groups (Circus and Robison, 2018; FSA, 2021, FSA, 2024b, FSA, 2024a; Survey Goo, 2018; Szejda et al., 2021; The Grocer, 2017)). A more detailed description of the evidence regarding each factor is provided below.

4.2.3.1. Age and gender

Most studies examined differences by age (FSA, 2021; FSA, 2024a; FSA, 2024b; Surveygoo, 2018; Szejda et al., 2021; The Grocer, 2017) and gender (FSA, 2021; FSA, 2024a; FSA, 2024b; Surveygoo, 2018; The Grocer, 2017), and consistently found that males and younger people were more likely to be willing to consume cell-cultivated meat. These findings are highly consistent with the international literature based in the USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand (FSA, 2020; FSANZ, 2023a).

4.2.3.2. Location

Only one study provided sufficient data to examine differences by country within the UK (the Food and You 2 survey; FSA, 2024a). Analysis of this survey data showed that people were more likely to be willing to consume cell-cultivated meat if they were from England, Wales or Scotland (rather than Northern Ireland). Although analysis of the FSA’s CIT survey data (FSA, 2024a) showed no significant differences between UK countries, analysis by country is more robust for the Food and You 2 survey due to the low sample sizes across some countries in the CIT survey. As previously discussed, there is also evidence that willingness to consume cell-cultivated meat is lower in the UK than in the USA (18% vs. 40%; Surveygoo, 2018, as cited in FSA, 2020)[3].

Analysis of the Food and You 2 survey data found no significant differences in consumption intentions between people who were from urban vs. rural locations (FSA, 2024b). Conversely, there is some evidence that urban vs. rural location may be a significant predictor of consumption intentions in the international literature. For example, qualitative research in New Zealand by Tucker (2014; as cited in FSA, 2020) found that urban participants were more willing to consume cell-cultivated meat than rural participants. The same pattern of results has also been observed in Ireland (Shaw & Mac Con Iomaire, 2019).

4.2.3.3. Socioeconomic status indicators

Only one UK study examined differences by level of education (the FSA’s CIT; FSA, 2024b). Analysis of this survey data showed that people were more willing to consume cell-cultivated meat if they were university educated (as opposed to not university educated). This finding is consistent with the international literature based in the USA, Canada and the Netherlands (FSA, 2020). Conversely, level of education was not a significant predictor of consumption intentions in Australia and New Zealand (FSANZ, 2023a).

The FSA’s Food and You 2 survey (FSA, 2024b) measured peoples’ socio-economic status via the National Statistics Socio-Economic Classification (NS-SEC), rather than by peoples’ level of education. The NS-SEC is widely used in official UK statistics, and assigns people to social classes based on their occupation (Office for National Statistics, 2021). In the Food and You 2 survey, NS-SEC was not a significant predictor of peoples’ willingness to try including cell-cultivated meat in their diet. Conversely, another UK survey (FSA, 2021) found that people with higher NS-SEC classifications were found to be more willing to try cell-cultivated meat (FSA, 2020). These differences may be due to the different measures used (willingness to include in the diet vs. willingness to try with no mention of including it in the diet) and/or different analytical methods (other demographics were controlled for when analysing the Food and You 2 survey data).

4.2.3.4. Other factors

Several additional factors beyond demographic differences were examined by two UK studies. This evidence suggests that people are more likely to be willing to consume cell-cultivated meat if they have a high meat attachment (where eating conventional meat forms part of one’s identity; Circus & Robison, 2018), are familiar with cell-cultivated meat terms, have no concerns about the product, believe there are benefits of the product, and feel confident that regulation will prevent the sale of unsafe cell-cultivated meat (FSA, 2024a).

These additional factors were not examined by the international literature in the FSA (2020) review. However, recent research in Australia and New Zealand found that people were more likely to be willing to consume cell-cultivated meat if they felt that they knew at least something about the product (as opposed to nothing) and felt confident in the safety of the product (FSANZ, 2023a). These measures are somewhat comparable to familiarity of the terms and confidence in regulation as measured in FSA (2024a). The same Australian/New Zealand research also found that people were more likely to be willing to consume cell-cultivated meat if they regularly (at least once a month) consumed plant-based meats. In addition, research from the USA found that those who were more politically liberal (rather than politically conservative) were more willing to consume cell-cultivated meat (FSA, 2020). Political views and plant-based meat consumption were not examined in the UK surveys.

4.2.3.5. What is the most important predictor?

Only two studies provided insight into the relative importance of different predictors. This evidence is from analysis of the FSA’s CIT survey data (FSA, 2024a) and Food and You 2 survey data (FSA, 2024a).

As previously described, the FSA’s CIT survey measured several demographic factors, as well as other factors such as familiarity of cell-cultivated meat terms, perceived concerns and benefits of cell-cultivated meat, and confidence in regulation. Binomial logistic regression analysis of this data revealed that the most important predictor was that people believed there were any benefits of cell-cultivated meat and felt confident that regulation will prevent the sale of unsafe products. Although other factors (including gender, age, education and familiarity of terms) were also statistically significant predictors, they only accounted for a relatively small amount of the variation in participants’ responses (R2 = 0.12; this substantially increased to 0.32 after adding both confidence in regulation and perceived benefits to the model)[4]. Interestingly, not having any concerns about cell-cultivated meat was not nearly as important as believing that there were any benefits (R2 did not increase from 0.12 when only perceived concerns were added to the model; whereas R2 increased to 0.27 when perceived benefits were also added).

Consistent with the CIT data, analysis of the Food and You 2 survey data (where perceived benefits and confidence in regulation were not measured) found that demographic variables such as gender, age, country and ethnicity only explained a relatively small portion of the variation in participants’ willingness to consume cell-cultivated meat (R2 = 0.06).

Further details of the binomial logistic regression models for both surveys are available in Appendix A (section 8.2).

4.2.3.6. Ethnicity and dietary pattern

Whether ethnicity or dietary pattern (e.g., vegetarians/vegans/pescatarians vs. omnivores) are significant predictors of peoples’ willingness to consume cell-cultivated meat is uncertain. This is due to the small number of vegetarians/vegans/pescatarians and people from ethnic minority groups that participated in all available surveys.

Analysis of the Food and You 2 data (FSA, 2024b) indicated that people of white ethnicity (compared to other ethnicities) were significantly more likely say they would consume cell-cultivated meat. Conversely, analysis of the CIT data (FSA, 2024a) indicated that ethnicity was not a significant predictor. Regardless, analysis of ethnicity was limited given that the majority of the sample identified as white across both surveys, and thus the sample size of other ethnicities was too small.

Analysis of the Food and You 2 data (FSA, 2024b) indicated that dietary pattern (vegans/vegetarians/pescatarians vs. omnivores) was not a significant predictor of peoples’ willingness to consume cell-cultivated meat. Conversely, evidence from another UK study (Surveygoo, 2018) suggests that vegans are more likely to be willing to consume cell-cultivated meat than vegetarians, pescatarians and omnivores. This finding is somewhat inconsistent with previous research indicating that people with a higher meat attachment are more likely to be willing to consume cell-cultivated meat (Circus & Robison, 2018). Surveygoo (2018) did not report whether there were any significant differences between vegetarians and omnivores.

The international literature based in the USA suggests that, although vegetarians may be more likely to have positive views of cell-cultivated meat compared to omnivores, they are less likely to want to consume it themselves (FSA, 2020). Whereas evidence in Australia and New Zealand suggests no significant differences between vegetarians/vegans and omnivores (FSANZ, 2023a). As with the UK evidence, analysis of dietary pattern within the international literature was limited due to the small sample of vegetarians/vegans/pescatarians that participated in all available surveys. In particular, analysis of both UK-based FSA surveys (FSA, 2024b, FSA, 2024a) and the Australian/New Zealand survey (FSANZ, 2023a) was even more limited given that it was necessary to combine vegetarians/vegans/pescatarians into one category, when other evidence suggests that vegans and vegetarians may have different consumption intentions (Surveygoo, 2018).

4.2.4. Has willingness to consume cell-cultivated meat changed between 2021 and 2023?

Wave 4 (FSA, 2022) and Wave 8 (FSA, 2024b) of the FSA’s Food and You 2 survey provides trend data on UK consumers’ willingness to try including cell-cultivated meat in their diet over a two year period. No trend data was available on willingness to consume cell-cultivated seafood, dairy or plants.

Wave 4 of the Food and You 2 survey included participants from England, Wales and Northern Ireland between October 2021 and January 2022. Whereas Wave 8 of the survey included participants from England, Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland between October 2023 and January 2024. Across both waves of the survey, participants were asked if they would like to try including lab-grown meat in their diet if it became available in their country (response options: I definitely would like to try this; I probably would like to try this; I probably would not like to try this; I definitely would not like to try this; don’t know).

As shown in Figure 1, the percentage of participants that were willing to try including lab-grown meat in their diet was similar across the two time periods.

Binomial logistic regression was used to determine whether there was a statistically significant difference in participants’ willingness to try including lab-grown meat in the diet across the two time periods. For this analysis, participants’ responses were dichotomised as generally willing (i.e., those who selected ‘I definitely would like to try this’ or ‘I probably would like to try this’) vs. generally unwilling or unsure (i.e., those who selected ‘I definitely would not like to try this’, ‘I probably would not like to try this’ or ‘don’t know’). Results of the binomial logistic regression analysis confirmed that willingness to try including lab-grown meat in the diet was not significantly different between the two time periods (B = 0.04, p = 0.635).

It is important to consider that, although consumption intentions have not changed within the past two years, it is possible that they may have changed over longer time periods. As previously discussed, UK studies that were conducted over seven years ago (Surveygoo, 2018; The Grocer, 2017) reported notably lower percentages of people willing to consume cell-cultivated meat than in more recent UK studies (see section 5.2.2). Research also suggests that consumers’ perceptions of cell-cultivated meat are highly malleable depending on the type of information received about the product (FSANZ, 2023b; University of Adelaide, 2023).

4.3. What are consumers’ attitudes towards cell-cultivated products?

This section addresses the following sub questions:

-

What do consumers see as the benefits of cell-cultivated products and what are their concerns?

-

What are consumers’ attitudes towards cell-cultivated products in relation to sustainability, shelf-life, cost and healthiness?

-

How do attitudes differ by demographics? What are the views of religious communities, for example, views on if these products are considered kosher/ halal, or vegetarian/ vegan

Consumer perceptions of the sustainability of cell-cultivated products is addressed in relation to Question 1, given that consumers perceive environmental impacts as a top three benefit of cell-cultivated products. Although cost and healthiness are not a top three perceived benefit or concern, further evidence was available on consumer perceptions of these factors more broadly. There was no available evidence on consumer perceptions of the shelf-life of cell-cultivated products. Only one study compared consumer perceptions between different religious groups (Muslims vs. non-Muslims), and none compared consumer perceptions based on dietary pattern (e.g., vegetarians/vegans vs. omnivores).

All findings are based on UK evidence, except where otherwise stated. Where evidence was available for both UK and international locations, findings were generally consistent. Most of the available evidence was available on cell-cultivated meat, with some evidence available on cell-cultivated seafood regarding consumer perceptions of the cost of cell-cultivated products. Only one international study examined consumer perceptions of cell-cultivated dairy.

4.3.1. Overview of key findings

-

Over half of people (59%) think cell-cultivated meat could offer benefits compared to traditional meat products, with the most common perceived benefits being that it is better for animal welfare (selected by 41% of people), more environmentally friendly/sustainable (34%) and will increase global food availability (33%).

-

However, most people (85%) also have concerns about cell-cultivated meat, particularly about it being safe to eat (selected by 50% of people), sounding unnatural (50%) and the impact on farmers (45%).

-

Evidence from Australia and New Zealand suggests that consumers perceive cell-cultivated dairy to be just as unsafe as cell-cultivated meat.

-

Perceived risks/concerns about cell-cultivated meat are more prevalent than perceived benefits.

-

People are more likely to think there are any benefits of cell-cultivated meat if they are:

-

Younger

-

University educated

-

Have a higher income

-

Live in urban (rather than rural) locations

-

Are from England (rather than Wales or Northern Ireland)

-

-

People are more likely to have any concerns about cell-cultivated meat if they are:

-

Older

-

University educated

-

Female

-

-

People are more likely to perceive cell-cultivated meat as being safe if they are:

-

Younger

-

Male

-

From a higher socio-economic group

-

Have previously heard of the product

-

-

USA evidence also suggests that people are more likely to perceive cell-cultivated meat as being safe if they are politically liberal (rather than politically conservative) or are white (as opposed to a non-white ethnicity).

-

Peoples’ perceptions of the healthiness/nutritional value of cell-cultivated meat relative to conventional meat appear to be highly malleable depending on the type of information received and product categories compared.

-

Most people are unwilling to pay more for cell-cultivated meat than farmed meat. However, USA evidence suggests that people may be willing to pay more for cell-cultivated seafood compared to farmed seafood, although not compared to wild-caught seafood.

-

Willingness to pay for cell-cultivated meat and seafood is generally higher when people are primed with positive information about the product.

A more detailed description of the evidence is provided below, grouped by research question: perceived risks/concerns and benefits of cell-cultivated products; broader perceptions/attitudes.

4.3.2. Perceived risks/concerns and benefits of cell-cultivated products

Two reviews (FSA, 2020; University of Adelaide, 2023) and six empirical studies ((Circus & Robison, 2018; Eom & Choy, 2024; Government Office for Science, 2015); FSA, 2022; FSA, 2024b, FSANZ, 2023b) examined consumers’ perceived risks/concerns and/or benefits of cell-cultivated products.

Overall, nine studies (including from the reviews) were based in the UK, and the UK findings were generally consistent with the international literature where available. Most of the available evidence examined cell-cultivated meat, with only one international study examining consumer perceptions of cell-cultivated dairy.

4.3.2.1. Perceived risks/concerns about cell-cultivated meat

The FSA (2020) and University of Adelaide (2023) reviews concluded that consumers have several concerns about cell-cultivated meat, including about its safety and perceived risks to personal health/nutrition, the environment, the economy and farmers. These conclusions were based on both international and UK studies. Concerns regarding the safety and healthiness of cell-cultivated meat were underpinned by perceptions of the product being unnatural and a lack of scientific understanding of the product. Environmental concerns related to the potential inefficient use of resources and views that cell-cultivated meat may not address the root cause of current environmental issues (the overconsumption of meat). The FSA (2020) review also identified more broader concerns about the taste, texture and appearance of cell-cultivated meat; this was not examined in the University of Adelaide (2023) review which only focused on consumers’ concerns within a risk context. Consistent with the conclusions of both reviews, four additional empirical studies found that most consumers either perceived cell-cultivated meat as unsafe (Government Office for Science, 2015; FSANZ, 2023b) or felt unsure about its safety (Eom & Choy, 2024; FSA, 2022).

However, the available (international and UK) evidence included in both reviews was limited such that studies tended to assess participants’ perceived risks of cell-cultivated meat within the context of the products not yet being available for sale on the market. It is therefore possible that participants may have different risk perceptions of cell-cultivated meat when it is available for sale (and possibly perceived as safer). Further, it was not possible to make a conclusion about the most prevalent type of perceived risk/concern, given that single studies tended to examine a limited number of concerns and these varied across different studies.

The FSA’s CIT survey (FSA, 2024a) builds on the evidence from the previously described research by examining UK consumers’ perceptions of a range of different types of perceived risks/concerns within the same study. This allowed conclusions to be drawn about the most prevalent types of concerns. Further, in contrast to most of the previous research, participants were provided with a statement that any product would need to go through a safety assessment before it was authorised to be sold.

When asked what concerns, if any, they had about cell-cultivated meat, most participants of the FSA’s CIT survey (85%) had some kind of concern about cell-cultivated meat. Consistent with previous research, the top three concerns were about its safety and unnaturalness (both selected by 50% of participants) and concerns about the impact on farmers (46%). Figure 2 shows the percentage of participants that selected each response option when asked if they had any concerns about cell-cultivated meat.

Other concerns that were identified by the University of Adelaide (2023) and FSA (2020) reviews included the ethical use of animals and the potential for a lack of transparency in the marketing/selling of cell-cultivated meat, with suspicions that it was primarily motivated by profit. Although these were not included as response options in the FSA’s CIT survey (FSA, 2024a), participants did not commonly identify these concerns through the ‘other’ (free response) option.

4.3.2.2. Perceived risks/concerns about cell-cultivated dairy

No study has thoroughly examined consumers’ concerns or perceived risks (or benefits) of cell-cultivated dairy. However, one international study examined consumers’ safety perceptions of cell-cultivated dairy, in addition to cell-cultivated meat (FSANZ, 2023a). In this study, a representative sample of Australian and New Zealand consumers were asked how confident they would be in the safety of ‘cell-based dairy’ if they saw it for sale in shops and supermarkets (response options on a scale from 1-7, where 1 = ‘not confident at all’ and 7 = ‘completely confident’). Most participants (63%) were generally not confident in the safety of cell-cultivated dairy (i.e., selected below the midpoint of the scale), similar to cell-cultivated meat (where 62% were not confident).

4.3.2.3. Perceived benefits of cell-cultivated meat

The FSA (2020) and University of Adelaide (2023) reviews also concluded that consumers believe there are some benefits of cell-cultivated meat However, these varied widely among consumers. Some believed there were benefits for the environment, animal welfare and future food security. Future food security was only considered a benefit if there were no risks to human health. Although some consumers were concerned about the healthiness and nutritional quality of cell-cultivated meat, others viewed these factors as potential benefits where improvements could be made relative to conventional meat. For example, O’Keefe et al. (2016; as cited in FSA, 2020Food Standards Agency (FSA), 2020) found that UK consumers discussed cell-cultivated meat as a way to avoid food scares such as mad cow disease and the potential to produce products with added vitamins and minerals. Consistent with the conclusions of both reviews, one additional UK study found that perceived benefits for the environment and animal ethics were top drivers for the consumption of cell-cultivated meat Circus & Robison, 2018.

However, the available (international and UK) evidence included in both reviews was limited such that most studies provided participants with biased descriptions of cell-cultivated meat that emphasised particular benefits and therefore primed them to discuss or select these. The FSA’s CIT survey (FSA, 2024a) again builds on the evidence from the previously described research by examining UK consumers’ perceptions of a range of different types of benefits within the same study. Further, in contrast to previous research, participants of the CIT were not previously primed with a description of cell-cultivated meat that emphasised particular benefits. Rather, participants were provided with a neutral description of what cell-cultivated meat is.

Analysis of the FSA’s CIT survey data (FSA, 2024a) revealed that over half of UK people (59%) think cell-cultivated meat could offer some kind of benefit compared to traditional meat. Consistent with the conclusions of the FSA (2020) and University of Adelaide (2023) reviews, perceived benefits varied among participants, with the most common (top three) perceived benefits being that it was better for animal welfare (selected by 41% of participants), more environmentally friendly/more sustainable (34%) and that it would increase the availability of food globally (33%). Figure 3 shows the percentage of participants that selected each response option when asked the question: ‘What benefits, if any, do you think cell-cultivated meat could offer compared to traditional meat products? Select all that apply’.

The University of Adelaide (2023) review also concluded that consumers generally feel less certain about the perceived benefits of cell-cultivated meat than the perceived risks. This is consistent with findings of the FSA’s CIT survey (FSA, 2024a), which found that having any concerns about cell-cultivated meat was more prevalent than the perception that it had any benefits (85% vs. 59%; see Figures 2 and 3). Similarly, an additional UK study (not included in the University of Adelaide and FSA reviews) found that, although participants acknowledged many environmental, future food security and animal welfare benefits of cell-cultivated meat, they were still generally opposed to it due to safety concerns (Government Office for Science, 2015).

4.3.2.4. Who is more likely to have concerns or believe there are any benefits?

Binomial logistic regression analysis of the FSA’s CIT data (FSA, 2024a) showed that people were more likely to have any concerns (as opposed to no concerns) about cell-cultivated meat if they were female, older, or university educated. While statistically significant (p-values < 0.05), these predictors only accounted for a small amount of the variation in participants’ responses (R2 = 0.03), suggesting that they only weakly predicted whether participants were likely to have any concerns. Country, urban vs. rural location, ethnicity and income were not significant predictors. Information about participants’ dietary patterns (vegetarian/vegan/pescetarian/omnivore) was not collected for this survey.

Binomial logistic regression analysis of the FSA’s CIT data (FSA, 2024a) also showed that people were more likely to think there were any benefits (as opposed to no benefits) of cell-cultivated meat if they were younger, university educated, had a higher income, were from an urban location (as opposed to a rural location), or were from England (as opposed to Wales or Northern Ireland). Again, these predictors only accounted for a small amount of the variation in participants’ responses (R2 = 0.04). Gender and ethnicity were not significant predictors. Further details of the binomial logistic regression models are available in Appendix A (section 8.2).

Demographic differences in perceived benefits/concerns were not thoroughly examined in the University of Adelaide (2023) or FSA (2020) reviews, although there was some UK-based evidence that Muslims were more likely than non-Muslims to perceive cell-cultivated meat as tastier, cheaper and more sustainable than conventional meat (Boereboom et al., 2022, as cited in University of Adelaide, 2023). However, these differences were small, with both Muslims and non-Muslims generally indicating that they neither agreed nor disagreed with these statements (i.e., rated them close to the midpoint of the rating scales). Further, Muslim perceptions were not examined within the context of the product being seen as Halal or not.

Two additional empirical studies investigated who was more likely to perceive cell-cultivated meat as safe (FSA, 2022; Eom & Choy, 2024). FSA (2022) found that people from the UK were more likely to perceive cell-cultivated meat as being safe if they were male, younger, from a higher socio-economic group, or had previously heard of it. Consistent with FSA (2022), Eom and Choy (2024) also found that people from the USA were more likely to perceive cell-cultivated meat as being safe if they were male. In addition, Eom and Choy (2024) examined political orientation and ethnicity (not examined by FSA, 2022) and found that people were more likely to perceive cell-cultivated meat as safe if they were politically liberal (rather than conservative) or white (rather than a non-white ethnicity). In contrast to FSA (2022) which surveyed UK consumers, Eom and Choy (2024) found that age was not a significant predictor of safety perceptions in the USA.

4.3.3. Broader perceptions/attitudes

The research described in the previous section examined consumer perceptions of cell-cultivated products within the context of perceived benefits, risks or concerns about the product. Whereas this section describes additional research that examined consumer perceptions/attitudes about the healthiness and cost of cell-cultivated meat more broadly (i.e., not within the context of these factors being framed as benefits or risks per say).

4.3.3.1. Consumer perceptions of the healthiness of cell-cultivated products compared to conventional products

The review by FSANZ (2023b) identified 15 studies that examined consumer perceptions of the healthiness of cell-cultivated meat relative to conventional meat. No evidence was available regarding cell-cultivated seafood or dairy. FSANZ (2023b) concluded that consumer perceptions of the relative healthiness of cell-cultivated meat was highly varied across different studies, likely due to differences in research methodologies across studies, including the type of terminology used (e.g., ‘cultured’ vs. ‘lab-grown’), type of descriptions provided about the product (neutral vs. biased descriptions emphasising healthiness), and the type of products examined. The authors suggested that this may indicate that consumer perceptions of the healthiness/nutritional value of cell-cultivated meat are highly malleable depending on the type of information received and product categories compared. These conclusions were based on both international and UK studies.

For example, a UK survey found that people perceived ‘cultured beef burgers’ to be just as unhealthy as conventional beef burgers, whereas ‘cultured chicken nuggets’ were perceived to be slightly healthier than conventional chicken nuggets (Vural et al., 2023; as cited in FSANZ, 2023a). In addition, an Australian survey found that conventional beef and chicken were perceived to be healthier than ‘lab-grown’ beef and chicken (de Oliveira Padilha et al., 2022; as cited in FSANZ, 2023a). While there is no evidence comparing consumers’ healthiness perceptions between Australia and the UK, there is evidence that terminology influences consumer perceptions of cell-cultivated products (with ‘cultured’ being more appealing than ‘lab-grown’; see section 5.4), which may account for the different findings between these two studies. FSANZ (2023b) also speculated that the different levels of processing implied between ‘beef’ vs. ‘beef burgers’ and ‘chicken’ vs. ‘chicken nuggets’ may have influenced how participants perceived the healthiness of these products compared to their cell-cultivated counterparts. The University of Adelaide (2023) review produced generally consistent conclusions, noting that consumer perceptions of the healthiness/nutritional quality of cell-cultivated meat was highly mixed across different studies.

Qualitative evidence from the FSANZ (2023b) review also indicated that consumer trust in scientists and companies producing cell-cultivated meat may affect perceptions of its healthiness and nutritional value. Consumers who had confidence in the individuals involved in the production process believed that they would make cell-cultivated meat nutritionally and healthfully equivalent to conventional meat.

As previously described, analysis of the FSA’s CIT survey found that, although cell-cultivated meat being less healthy than conventional meat was a concern for some participants (27%), it was not a top-of-mind issue compared to other concerns (such as safety, unnaturalness and impacts on farmers; see Figure 2). Similarly, although cell-cultivated meat being more healthy than conventional meat was seen as a potential benefit for some participants (9%) it was not a top-of-mind benefit compared to other factors (such as benefits for animal welfare, the environment or global food availability; see Figure 3).

4.3.3.2. Consumer perceptions of the cost of cell-cultivated products

Four studies examined consumer perceptions of the cost of cell-cultivated meat and/or seafood (Chuah et al., 2024; Circus & Robison, 2018; Kovacs et al., 2024; Szejda et al., 2021). Evidence from the UK and USA suggests that most consumers are not willing to pay more for cell-cultivated meat than farmed meat. Conversely, USA evidence indicates that people may be willing to pay more for cell-cultivated seafood compared to farmed seafood, but not compared to wild-caught seafood. Across both countries, willingness to pay for cell-cultivated meat and seafood is generally higher when people are primed with positive information about the product.

In the study by Szejda et al. (2021), less than half (45%) of UK participants indicated that they would be willing to pay a higher price for cell-cultivated meat than for conventional meat. However, this may be an overestimation given that participants in this study were provided with biased response options. That is, four out of the five response options indicated a willingness to pay more for cell-cultivated meat ('not at all likely, ‘somewhat likely’, ‘moderately likely’, ‘very likely’, ‘extremely likely’). Participants were therefore more likely to select a response category indicating a willingness to pay more due to chance, or may have assumed that a willingness to pay more was the ‘correct’ answer since it was most prevalent in the response options. Participants in this study were also provided with a description of “cultivated meat” that emphasised its benefits prior to answering this question. Research by Chuah et al. (2024) and Kovacs et al. (2024) suggests that people are willing to pay more for cell-cultivated meat/seafood when provided with positive information about the product (compared to when provided with neutral information). Other research has also found that the term “cultivated” is more appealing to consumers than other terms such as “cell-based” or “lab-grown” (see section 5.4).

The research by Kovacs et al. (2024) found that USA participants were willing to pay less for “lab-grown” meat than conventional (farmed) meat. This is generally consistent with Szejda et al.'s (2021) finding that less than half of people in the UK were willing to pay more for “cultivated meat” than conventional meat. Additionally, the difference in price point between lab-grown meat and conventional meat in Kovacs et al. (2024) was smaller when consumers were provided with positive information about lab-grown meat, however, participants were still willing to pay less for lab-grown meat than conventional meat regardless.

The research by Chuah et al. (2024) examined USA consumers’ willingness to pay for “cell-based” seafood. When provided with neutral information about cell-based seafood products, willingness to pay was highest for wild-caught seafood, followed by cell-based seafood, followed by farm-raised seafood. This is inconsistent with the findings of Kovacs et al. (2024) and Szejda et al.'s (2021), which suggest that consumers are not willing to pay more for cell-cultivated meat than farmed meat. Willingness to pay more for cell-cultivated products than farm-raised products (as found in Chuah et al., 2024) may therefore be specific to seafood. It is unknown whether this finding is generalisable to UK consumers. Consistent with the findings of Kovacs et al. (2024), Chuah et al. (2024) found that positive information about cell-based seafood, particularly about it being contaminant-free, increased the amount people were willing to pay for it. Although this still was not as high as willingness to pay for wild-caught seafood.

Finally, Circus and Robinson (2018) found that cost did not emerge as a prominent barrier to consumption of “lab-grown meat”, despite its relatively high cost communicated to UK participants. Although participants in this study were provided with an information sheet emphasising the environmental benefits of lab-grown meat, these findings are consistent with the findings of FSA’s CIT survey (FSA, 2024a) where participants were provided with neutral information about the product. As previously described, analysis of the FSA’s CIT survey found that, although a high cost was a concern for some participants (28%), it was not a top-of-mind issue compared to other concerns (such as safety, unnaturalness and impacts on farmers; see Figure 2). Similarly, although a low cost compared to traditional meat was seen as a potential benefit for some participants (22%) it was not a top-of-mind benefit compared to other factors (such as benefits for animal welfare, the environment or global food availability; see Figure 3).

4.4. How does the terminology applied to cell-cultivated products influence consumer perceptions and understanding?

Two reviews (FSANZ, 2023b; University of Adelaide, 2023) and two empirical studies (Hallman et al., 2023; the Good Food Institute [GFI], unpublished) examined the effect of different terminologies applied to cell-cultivated products on consumer perceptions and understanding. Evidence was available on both cell-cultivated meat (beef and chicken) and seafood. No studies examined this research question in relation to cell-cultivated dairy or plants.

The available studies measured consumer understanding of the true nature of the product (i.e., that it is not wild-caught nor farm-raised), and of the safety of the product for those with an allergy to the conventional counterpart. Other broader consumer perceptions that were measured included acceptance/appeal, awareness/familiarity, overall safety, nutrition/healthiness of the product, and whether the product was seen as natural, organic and genetically modified (GM).

4.4.1. Overview of key findings

-

No terminology achieves 100% consumer understanding of the true nature of cell-cultivated meat or seafood (i.e., that the product is neither wild-caught nor farm-raised).

-

Terms that incorporate the word ‘cell’ (e.g., ‘cell-cultivated’, ‘cell-cultured’ and ‘cell-based’) enable most consumers to correctly identify that the product is neither wild-caught nor farm-raised.

-

However, terms that incorporate the word ‘cell’ are less appealing to consumers than the terms ‘cultured’ or ‘cultivated’.

-

Terms containing the word ‘cell’ are also perceived as more likely to be GM and less natural compared to the terms ‘cultured’ or ‘cultivated’.

-

Consumers generally have a poor understanding of the terms ‘cultured’ and ‘cultivated’, and the higher consumer appeal of these terms may disappear once consumers become more familiar with cell-cultivated products.

-

While consumers are most familiar with the term ‘lab-grown’ and generally understand that it does not mean wild-caught nor farm-raised, it causes consumers to perceive the product as being less safe compared to other terms.

-

The term ‘artificial’ causes consumers to incorrectly perceive the product as plant-based.

-

Consumer awareness of the allergenicity of cell-cultivated meat and seafood is low. The terms that most effectively convey the true nature of the product (‘cell-cultured’, ‘cell-cultivated’) are only correctly understood by up to 66% of consumers as being unsafe for individuals with an allergy to the conventional counterpart, and are perceived as safer than the conventional counterpart.

-

The term ‘cell-based’ may produce lower levels of perceived allergenicity than other terms that incorporate the word ‘cell’. Regardless, terminology alone is insufficient to effectively communicate allergen information to consumers.

-

Although there is some evidence that terminology may influence consumers’ perceived nutrition/healthiness of the product, findings are mixed, and the available evidence is limited such that few terms have been directly tested.

A more detailed description of the reviews and empirical studies is provided below, grouped by the type of measures examined: consumer acceptance and understanding; awareness/familiarity; perceived nutrition and healthiness.

4.4.2. Consumer acceptance and understanding of different terminologies

This subsection describes two reviews (FSANZ, 2023b; University of Adelaide, 2023) and two empirical studies (Hallman et al., 2023; GFI, unpublished) that examined consumer acceptance and understanding of different terminologies. Most of the evidence was based in the USA; only two studies were based in the UK (Szejda et al., 2021, as cited in FSANZ 2023a and University of Adelaide, 2023; GFI, unpublished). Nevertheless, findings from the UK studies were highly consistent with the international studies.

4.4.2.1. Consumer acceptance and understanding of the true nature of the product

The review by FSANZ (2023b) included 11 studies that measured consumer understanding of cell-cultivated meat and/or seafood in various ways. Two of these 11 studies were experimental designs where participants from the USA were randomly assigned to view one of many different terminologies (Hallman & Hallman, 2020; Malerich & Bryant, 2022). Objective understanding was measured by asking participants to accurately identify the product (e.g., not wild-caught salmon, not farm-raised animals, not plant-based). Participants’ acceptance of the products was also measured in several different ways, including how likely they were to purchase the product and how positively they rated their first thought, image or feeling that came to mind when viewing the product. Importantly, these studies did not provide participants with a description of what cell-cultivated meat/seafood is, meaning that consumer understanding and appeal was examined based solely on the terminology used.

Based on these two studies, FSANZ (2023b) concluded that terms that incorporate the word ‘cell’ (e.g., ‘cell-cultivated’, ‘cell-cultured’ and ‘cell-based’) best enable consumer understanding of the true nature of the product, but may decrease consumer appeal compared to the terms ‘cultured’ or ‘cultivated.’ Consumers generally have a poor understanding of the terms ‘cultured’ and ‘cultivated’ across all products (seafood, chicken and beef), although the problem is more salient for seafood. While the term ‘lab-grown’ is just as effective as ‘cell’-type terms in enabling consumers to accurately identify the product, it also causes consumers to perceive the product as being less safe compared to other terms. In addition, the term ‘artificial’ causes consumers to incorrectly perceive the product as being plant-based.

The remaining nine studies included in the FSANZ (2023b) review measured consumers’ perceived understanding of cell-cultivated meat (e.g., Dillard & Szejda, 2019; Szejda, 2018; Szejda et al., 2020, 2021), which may differ from actual understanding. These studies assessed USA and/or UK participants’ beliefs about how well the name described the product and whether they thought it would help them distinguish the product from traditional meat or plant-based alternatives. Typically, these studies presented participants with favourable descriptions of cell-cultivated meat, emphasizing benefits such as improved human health and environmental impact, or similarities in taste, texture, and nutrition to conventional meat, before evaluating their perceptions. Nevertheless, findings were consistent with the more objective studies (Hallman & Hallman, 2020; Malerich & Bryant, 2022), such that participants perceived terminologies that incorporated the word ‘cell’ to be the most descriptive and as best enabling them to differentiate the product from conventional meat/plant-based meat alternatives. Also consistent with the more objective studies, the terms ‘cultured’ and ‘cultivated’ were generally more appealing (‘somewhat’ to ‘moderately’ appealing) than terms that incorporated the word ‘cell’ (‘not at all’ to ‘somewhat’ appealing).

One key difference in findings between these different types of studies is that participants tended to perceive the terms ‘cultured’ and ‘cultivated’ as enabling them to differentiate cell-cultivated meat from conventional meat to a moderate extent. Conversely, research by Hallman et al. (2020) and Malerich and Bryant (2022) found that a relatively small percentage of consumers can correctly identify the product when the terms ‘cultured’ and ‘cultivated’ are used. It is also important to note that the studies examining perceived understanding did not include seafood, where difficulties with the terms ‘cultured’ and ‘cultivated’ are more salient.

A second review undertaken by the University of Adelaide (2023) on this topic produced highly consistent findings. In addition, the authors concluded that, although terminologies that incorporate the word ‘cell’ are best understood by consumers, no terminology achieves 100% correct identification that the product is neither wild-caught nor farm-raised. Indeed, the product was correctly identified by up to 61% of participants in Hallman and Hallman’s (2020) study, and by more than 80% of participants in Malerich and Bryant’s (2022) study.

A likely explanation for the higher rate of accuracy in Malerich and Bryant’s (2022) study is that participants were cued to the true nature of the product via the inclusion of a response option that specifically referred to animal cells (e.g., is this product hunted in the wild, farm raised, produced by animal cells in a food facility, or plant-based?). Conversely, in Hallman and Hallman’s (2020) study, participants were more generally asked if the product was hunted, farmed or neither. Nevertheless, if consumers become familiar with the concept of cell-cultivated products, then the context of Malerich and Bryant’s (2022) study may reflect real-world contexts where participants view products in a supermarket setting with some prior knowledge of the product.

Two additional studies not included in the FSANZ (2023b) or University of Adelaide (2023) reviews also produced consistent findings (Hallman et al., 2023; GFI, unpublished).In Hallman et al. (2023), USA participants were randomly assigned to view one type of terminology (cell based, cell-cultured, cell-cultivated, cultured, cultivated, or no term) on one type of protein (chicken breasts, chicken burgers, beef fillets, beef burgers, salmon fillets, or salmon burgers). Similar to previous research, participants were asked whether the beef/chicken/salmon can be best described as grass fed/free range/wild caught, grain fed/raised indoor/farm raised, or neither. Participants were also asked how confident they were in their answers (1 = not at all; 2 = slightly; 3 = moderately; 4 = very, 5 = extremely), and how safe it would be for them to eat the product if they were allergic to beef/chicken/salmon (1 = very unsafe; 2 = moderately unsafe; 3 = somewhat unsafe; 4 = neither safe nor unsafe; 5 somewhat safe; 6 moderately safe; 7 very safe). Participants were not provided with a description of what cell-cultivated meat/seafood is prior to answering these questions.

Consistent with previous research, Hallman et al. (2023) found that the terms ‘cultured’ and ‘cultivated’ generally performed worst at enabling consumers to accurately identify the true nature of the products. More specifically, ‘cultured’ and ‘cultivated’ performed significantly worst for salmon products (accurately identified by 33-49% of participants vs. 58-71% for ‘cell’-type terms), and ‘cultivated’ performed worst for beef fillets (57% vs. 70-78% for ‘cell’-type terms). Although terminology had no significant effect on participants’ ability to accurately identify the beef burgers or chicken products, participants were significantly less confident in their answers when products were labelled as ‘cultivated’ (M = 3.01) or ‘cultured’ (M = 2.98) compared to when they were labelled as ‘cell-cultivated’ (M = 3.22) or ‘cell-cultured’ (M = 3.21) across all types of proteins.

Similar research methods were used by the GFI (unpublished), except that the GFI used a large representative sample of the UK. The GFI tested the terms ‘cultivated’, ‘cell-cultivated’, ‘cultured’ and ‘artificial’, as well as the descriptive phrases ‘made without farming (or fishing) animals’, ‘made from cellular agriculture’, and ‘made from synthetic protein’ on chicken pieces, beef mince, and salmon fillets. After being randomly allocated to view one term or descriptor on one type of protein, participants were asked if they think the product is made by farming (or catching) animals (response options: yes/no).

GFI (unpublished) found that the group who saw the term ‘cell-cultivated’ had a better understanding of the true nature of the product (55% of participants correctly responded ‘no’ to the product being produced by farming/fishing animals) compared to the groups that saw the terms ‘cultured’ and ‘cultivated’ (28% and 26% correctly responded ‘no’, respectively). An even higher percentage of participants correctly responded ‘no’ in the group that saw the term ‘artificial’ (67%) and the descriptive phrases ‘made without farming (or fishing) animals’ (63%), and ‘made from synthetic protein’ (58%). However, this may be attributed to participants in these groups being more likely to incorrectly perceive the product as plant-based (42-64% of those who saw the term ‘artificial’ and the descriptive phrases responded ‘no’ when asked if the product is made from plant-based ingredients, compared to 72-79% across the other groups). Furthermore, after being provided with a neutral description of the product, participants most commonly selected ‘cell-cultivated’ as the clearest term for communicating that the product is different from plant-based or farmed/fished meat/seafood (41% ranked ‘cell-cultivated’ as being the most clear, compared to 25% selecting ‘cultivated’, 24% selecting ‘artificial’ and 10% selecting ‘cultured’). Participants also selected ‘made without farming animals’ as the clearest descriptor (ranked first by 41%, compared to 25% selecting ‘made from cellular agriculture’ and 24% selecting ‘made from synthetic protein’)[5]. However, it is important to consider that a substantial percentage of participants thought that ‘made without farming (or fishing) animals’ implied that the product was plant-based (46%, compared to 28% for the term ‘cell-cultivated’). The study did not examine consumers’ objective understanding of the product when both ‘cell-cultivated’ and ‘made without farming (or fishing) animals’ was included on the label.

The research by Hallman et al. (2023) also further builds on the evidence from the FSANZ (2023b) and University of Adelaide (2023) reviews by suggesting that the higher consumer appeal of the terms ‘cultivated’ and ‘cultured’ may disappear once consumers become more familiar with the product. That is, Hallman et al. (2023) found that before learning of the meaning of the terminologies, participants perceived the terms with the word ‘cell’ incorporated as less natural than the terms ‘cultured’ and ‘cultivated’, and were slightly less interested in tasting, purchasing, ordering or serving products with the terms ‘cell-based’ and ‘cell-cultivated’. However, after participants were provided with a description of what the product was, these effects become non-significant. Further, ratings significantly reduced across all measures after participants read the description (compared to before they read the description), particularly for the term ‘cultivated’. The authors speculated that this may indicate the possibility of a consumer “backlash” from learning that their initial perceptions of these terms were incorrect. While this could very well be the case, it is also important to consider that the products were described to participants in this study as “tasting, looking, and cooking the same and having the same nutritious qualities as Beef/Chicken/Salmon produced in traditional ways”, which may not necessarily be true for all cell-cultivated products on the market in future.

Consistent with Hallman et al. (2023), although the research by GFI (unpublished) only measured participants’ purchase intentions after viewing a neutral description of cell-cultivated meat (i.e., not before and after), differences in participants’ purchase intentions were minimal between the different groups. That is, 35% of participants that saw the term ‘cell-cultivated’ said they would be likely to purchase the product, compared to 36% of those who saw the term ‘cultured’ and 40% of those who saw the term ‘cultivated’. Overall, the percentage of participants who reported that they would be likely to purchase the product is similar to the percentage of participants reporting that they would be likely to consume the product, as found in other studies (see section 5.2.2).

4.4.2.2. Consumer understanding of the allergenicity of cell-cultivated products

The two experimental studies included in FSANZ’s (2023b) review also examined the effect of different terminologies on consumer understanding of the allergenicity of cell-cultivated meat/seafood products (Hallman & Hallman, 2020; Malerich & Bryant, 2022). Consumer understanding was measured by asking participants whether the cell-cultivated product would be safe for individuals with allergies to its conventional counterpart. Based on these two studies, FSANZ (2023b) concluded that terminology alone cannot sufficiently convey allergen information to consumers. That is, for the terms that best conveyed the true nature of cell-cultivated products (‘cell-cultivated’, ‘cell-cultured’ and ‘cell-based’), only up to 66% of consumers correctly identified that cell-cultivated meat/seafood was not safe to consume for people with an allergy to conventional meat/seafood. The term ‘cell-based’ performed worst at communicating allergenicity for beef products in particular (correctly identified as not safe by only 38% of participants).