Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the chicken processing sites visited in this project for their generous access to their data and support and access to their sites.

The authors would like to thank Miss Hamida Musah Alhassan, Mr Oliver Horne, Miss Sophie Bowers, Mr Bamidele Adedeji, Mr Jesse Adenola, Dr Essam Hebishy, and Dr Samson Oyeyinka for their involvement in the sample collection and sample preparation stages of this project.

We would also like to thank the UK Food Standards Agency for funding this work.

Glossary and abbreviations

| Term/Abbreviation |

Definition/Description |

| Antibiotic |

An antibiotic is a drug used to treat bacterial infections. Such agents have no effect on viral or fungal infections. Examples of antibiotics include penicillins, tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones and polymyxins such as colistin. Antibiotic growth promoters (AGPs) have been used as additives to improve feed efficiency in food animals. Their use for this purpose has been banned in EU countries, including the UK, since the early 2000s but some AGPs are still licensed for use in some countries. |

| Antimicrobial |

Any substance that kills or stops the growth of microorganisms, such as antibiotics, antifungals, biocides, and preservatives. |

| AMU |

Antimicrobial use |

| AMR |

Antimicrobial resistance.

For the interpretation of AMR, the WHO definition was applied (WHO, 2018): “Antimicrobial resistance is resistance of a microorganism to an antimicrobial drug that was originally effective for treatment of infections caused by it. Resistant microorganisms (including bacteria, fungi, viruses, and parasites) are able to withstand attack by antimicrobial drugs, such as antibacterial drugs (e.g., antibiotics, antifungals, antivirals, and antimalarials), so that standard treatments become ineffective, and infections persist, increasing the risk of spread to others.” |

| ARG(s) |

Antimicrobial resistance gene (s).

An ARG is a gene implicated in or associated with conferring phenotypic resistance to one or more antimicrobial. The resistance may result from the presence or absence of a gene, or specific mutations acquired spontaneously or accumulated through evolution over time. Although ARGs confer resistance, clinical treatment with higher doses of the antimicrobial may still be effective. |

| Bacteriophage |

Often shortened to phage (as in this report), a bacteriophage is a virus that parasitises a bacterium by infecting it and reproducing inside it. Phages are capable of packaging part of their host’s genetic material (including ARGs) either by reproducing within the host cell before lysing the cell (lytic) or through incorporation into the host cell genome (lysogenic). Phages cannot infect human cells. |

| Biofilm |

A community, which may consist of one or more types of bacteria and also other microorganisms. Biofilms attach to a surface (biotic or abiotic) and are covered by an extracellular substance, which may afford protection from an antimicrobial, due to lack of, or slower penetration of the biofilm. Organisms may grow slower in a biofilm and enter a hyper-mutable state and such proximity of bacterial cells may help promote Horizontal Gene Transfer. |

| BIOHAZ Panel |

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) Panel on Biological Hazards. |

|

blaTEM

|

An ARG conferring resistance to β-lactam antibiotics located on a family of related β-lactamase plasmids. |

|

blaCMY-2

|

A family of the AmpC β-lactamase genes that confer broad-spectrum resistance to β-lactam antimicrobials, including ceftriaxone and ceftiofur, as well as to β-lactamase inhibitors, such as clavulanic acid. |

|

blaCTX-M

|

An ARG conferring extended spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) resistance against a wide range of β-lactam antimicrobials by different transposons and Insertion sequences (IS). |

| Breakpoint |

Breakpoints are the values used by clinical microbiology laboratories to interpret the results of antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) and classify isolates as susceptible or resistant. |

| CFU |

Colony-forming unit

A CFU is a unit which estimates the number of microbial cells (bacteria, fungi, viruses etc.) in a sample that are viable and able to multiply via binary fission under controlled conditions, i.e. the number of colonies counted on a petri dish. |

| CIAs |

‘Critically Important Antimicrobials’ (WHO terminology).

There are some differences in the categorisation of CIAs between different organisations. The WHO (WHO, 2018) categorises CIAs as meeting two criteria:

Criterion 1 (C1): The antimicrobial class is the sole, or one of limited available therapies, to treat serious bacterial infections in people.

Criterion 2 (C2): The antimicrobial class is used to treat infections in people caused by either: (1) bacteria that may be transmitted to humans from non-human sources, or (2) bacteria that may acquire resistance genes from non-human sources. |

| Commensal |

An organism that co-exists in the internal or external environment of the host, without causing harm, as far as is known. |

| DNA |

Deoxyribonucleic acid.

Deoxyribonucleic acid is a molecule composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix carrying genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of all known organisms and many viruses. |

| ECOFF |

Epidemiological Cut Off value (with respect to antimicrobial resistance): represents the point (breakpoint) at which bacteria have developed a higher level of resistance to an antimicrobial agent than the background level of resistance that exists naturally for that bacterial species. A ‘resistant’ (or ‘non-susceptible’) ECOFF does not necessarily imply a level of resistance which would correspond with clinical treatment failure. |

| EFSA |

European Food Safety Authority. |

| ESBL(s) |

Extended spectrum beta-lactamases.

ESBLs are enzymes produced by bacteria such as Escherichia coli and Klebsiella species. ESBLs mediate resistance to 3rd/4th generation cephalosporins. |

| EUCAST |

European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| FAO |

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. |

| FSA |

Food Standards Agency. |

| Genome |

The genetic information of an organism. |

| Gram-negative bacteria |

Gram-negative bacteria are characterised by their cell envelopes, which are composed of a thin peptidoglycan cell wall sandwiched between an inner cytoplasmic cell membrane and a bacterial outer membrane. They do not retain the crystal violet stain used in the Gram staining method of bacterial differentiation. Pathogenic Gram-negative bacteria are increasingly resistant to most available antimicrobials. They have built-in abilities to find new ways to be resistant and can pass along genetic materials that allow other bacteria to become drug resistant. Gram-negative bacteria are generally more resistant to antimicrobials than Gram-positive bacteria. |

| Gram-positive bacteria |

Gram-positive bacteria have a thick peptidoglycan layer in the bacterial cell wall which allows for the take up the crystal violet stain used in the Gram staining method of bacterial differentiation. Gram-positive bacteria appear to be purple-coloured when seen through an optical microscope. |

| gyrA |

Mutation in this gene can confer resistance to ciprofloxacin and nalidixic acid. |

| HGT |

Horizontal Gene Transfer

Transfer of genetic material (including ARGs), among different bacteria and species, other than by the transmission of DNA from parent to daughter cell. There are a number of different mechanisms through which HGT can occur. |

| Integron |

A type of mobile genetic element (MGE) with the ability to capture and disseminate genes (including ARGs). These genes are located on gene cassettes (a term that is changing to integron cassette), though an integron does not necessarily include any gene cassettes. Integrons can be found in plasmids, chromosomes, and transposons. |

| MDR |

Multidrug Resistance.

Resistance of a bacterial isolate to three or more classes of antimicrobial. |

| Metaphylactic |

Treatment of a group of animals without evidence of disease, which are in close contact with other animals that do have evidence of infectious disease. |

| MIC |

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration.

The lowest concentration of an antimicrobial that prevents visible growth of a bacteria in a liquid or agar test. |

| Microbiota |

The assemblage of living microorganisms present in a defined environment. |

| Microorganisms (microbes) |

Organisms that include bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites. |

| MGE(s) |

Mobile Genetic Element (s).

MGEs, also known as transposable elements (TEs), are fragments/sequences of DNA that can be transported between bacteria. They can encode a variety of virulence or resistance determinants (such as ARGs) that can change places on a chromosome, and can be transferred between chromosomes, between bacteria, sometimes including different species. Types of MGEs include plasmids, integron gene cassettes, and transposable elements. |

| NAP |

National Action Plan

UK Government 5-year (2024 to 2029) AMR National Action Plan (NAP) for tackling antimicrobial resistance. |

| PCR |

Polymerase chain reaction

A laboratory technique that amplifies specific DNA or RNA segments to detect and analyse genetic material. |

| Phylum |

A grouping together of related organisms on the basis of their fundamental characteristics. It is the third most broad category of taxonomy, falling between kingdom and class. |

| Plasmid |

A type of MGE in a cell that can replicate independently of the chromosome(s), typically a small circular double DNA strand in the cytoplasm of a bacterium. Plasmids can carry and transfer ARGs from the host to other cells, via other MGEs (integron gene cassettes and transposable elements). |

| Shotgun metagenomic sequencing |

The untargeted ('shotgun') sequencing of all ('meta-') microbial genomes ('genomics') present in a biological sample. Shotgun sequencing can be used to profile taxonomic composition and functional potential of microbial communities and to recover whole genome sequences. |

| Spp. |

Species. |

| ST |

Sequence type

An unambiguous procedure for characterising isolates of bacterial species using the sequences of internal fragments of (usually) seven house-keeping genes. |

| Tet(A) |

An ARG found in Gram-positive bacteria, and which confers resistance to tetracycline group of antibiotics -chlortetracycline, doxycycline, and minocycline - by encoding a tetracycline efflux protein. |

| Therapeutic use |

Use of antimicrobials to treat individual humans or animals (or groups of animals) suffering from a bacterial infection. |

| WGS |

Whole-Genome Sequencing

WGS reveals the complete DNA make-up of an organism, enabling an understanding of variations both within and between species. |

| WHO |

World Health Organisation (of the United Nations). |

Lay Summary

The emergence and spread of resistance to antimicrobials in bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites is of global concern. There is increasing concern that the food chain and food processing environments may significantly contribute to the transmission of antimicrobial resistant bacteria and genes (ARGs), potentially serving as hotspots for the acquisition and spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). However, relatively little is known about the role of the food chain in the transmission of AMR bacteria in general, including the transmission and prevalence of AMR bacteria in chicken and chicken products, before retail. The overall aim of this project was to access the impact that processing has on the presence and transfer of antimicrobial resistant Campylobacter species (spp.) and Escherichia coli and associated genes on chicken meat. Since poultry accounts for half of the meat eaten in the United Kingdom (UK) it potentially represents a significant reservoir for AMR to transfer to humans. This project therefore was intended to act as a baseline for work comparing two similar typical large scale UK chicken plants using traditional and newer approaches, as well as an incentive for further testing, to establish the importance of different processing steps in AMR transmission and identify mitigating strategies for reducing and eliminating persistence and transmission of AMR.

This project was carried out in two parts. Part 1. an initial literature review which was carried out to aid the project sampling plan/design and part 2. a field and laboratory study conducted to assess the presence and potential transmission of AMR- Campylobacter spp. and E. coli during the processing of chicken in two similar sized large scale UK chicken processing sites producing whole chickens and chicken meat for major UK retailers at different points in the year.

Key findings

Our literature review found that:

-

Few published studies have investigated the transmission of AMR bacteria or ARGs during poultry processing, with existing research suggesting that AMR and ARGs in outgoing meat are primarily influenced by farm-level factors rather than in-plant procedures. There is limited published evidence on the transmission and persistence of AMR bacteria and genes occurring in processing environment.

-

No published studies have looked at the impact of physical interventions (such as steam) that may be employed to reduce pathogenic contamination on chicken carcasses on the transmission of AMR. Such interventions are now being employed by some UK chicken processors and employed in both plants studied in this project.

Our field and laboratory study found that:

-

Of the 376 samples collected from the poultry plants during this current project, 65.1% of samples were positive for presence of Campylobacter spp. and 95.6% were positive for presence of E. coli.

-

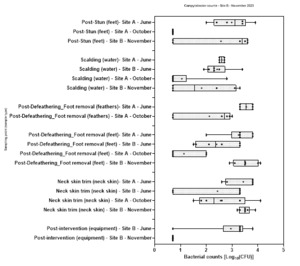

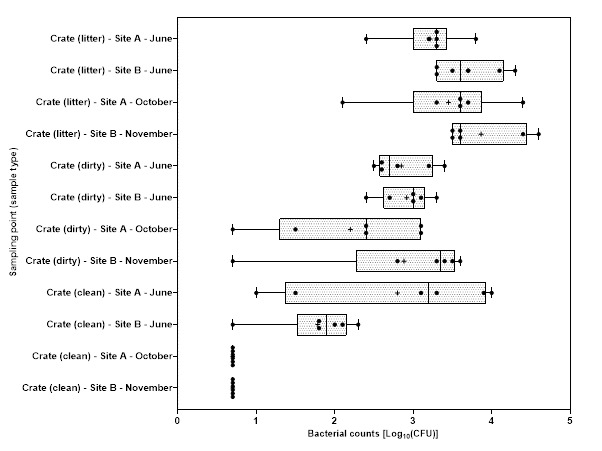

Levels of Campylobacter spp. isolated from sample collected from the 2 UK plants ranged from 1.00±0.0 to 3.9±0.5 log10 Colony Forming Units (CFU) per sample; with the highest level recorded from chicken litter and the lower levels recorded from post intervention equipment, scalding water, clean crates, and on carcasses at dispatch.

-

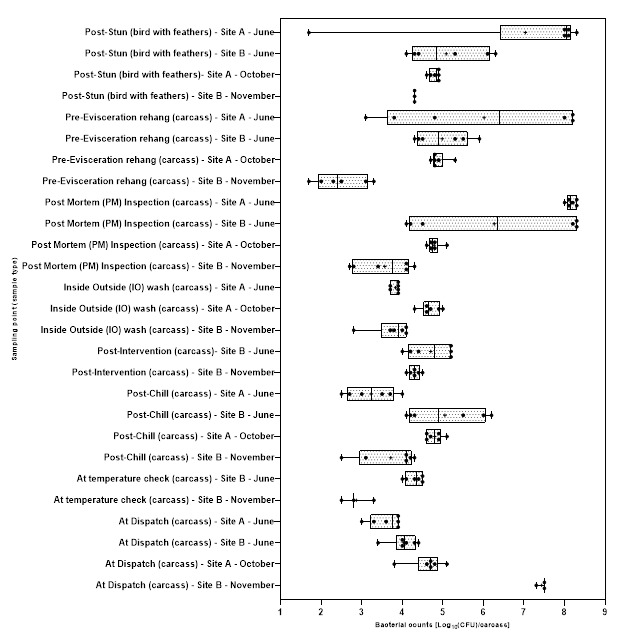

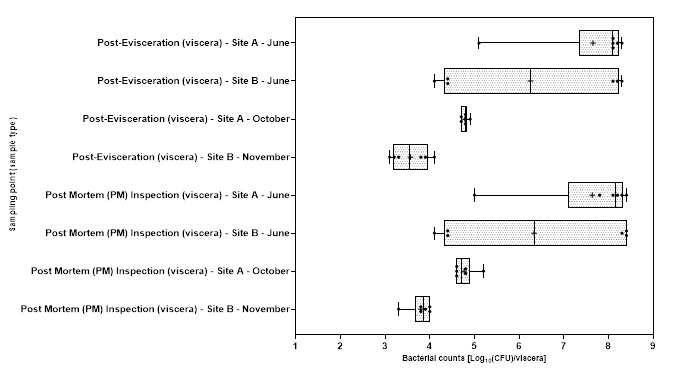

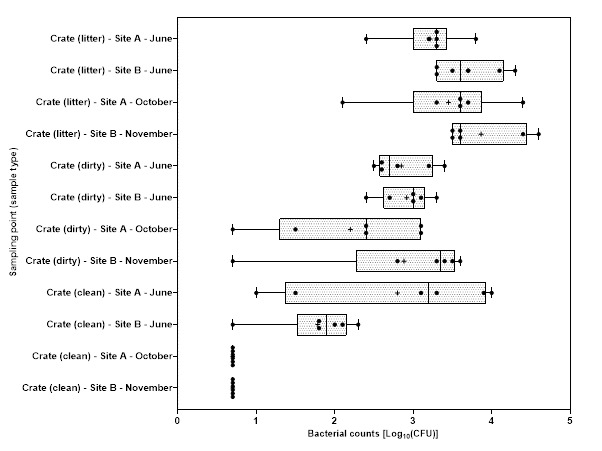

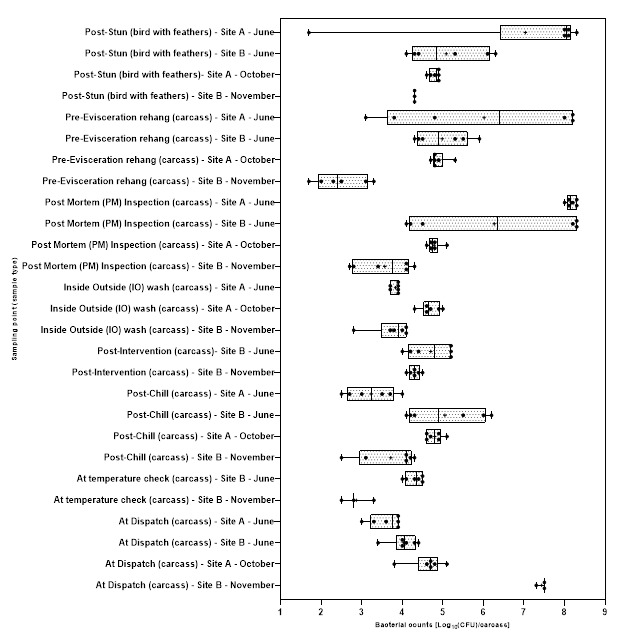

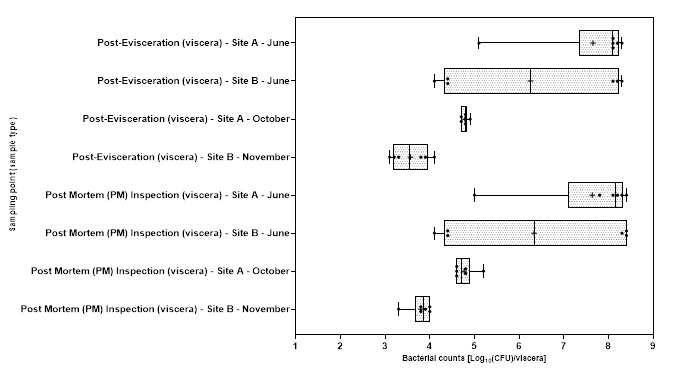

Levels of E. coli isolated from sample collected from the 2 UK plants ranged from 2.0±0.0 to 8.3±0.2 log10 CFU per sample; with the highest level recorded from chicken litter and the lower levels recorded from post intervention equipment, post intervention carcasses, scalding water, post chill, inside outside wash and clean crate processing stages.

-

Campylobacter spp. and E. coli were detected at different stages throughout the production process in both plants, with higher numbers measured at the earlier stages of the process in both plants.

-

At some stages of the process no Campylobacter spp. or E. coli were isolated in either plant.

-

Generally, levels of Campylobacter spp. decreased to non-detectable levels in samples taken further along the processing stages. For E. coli while there was a general decrease in the level of the organisms, samples tested at the later stages of processing remained still positive for the presence of E. coli.

-

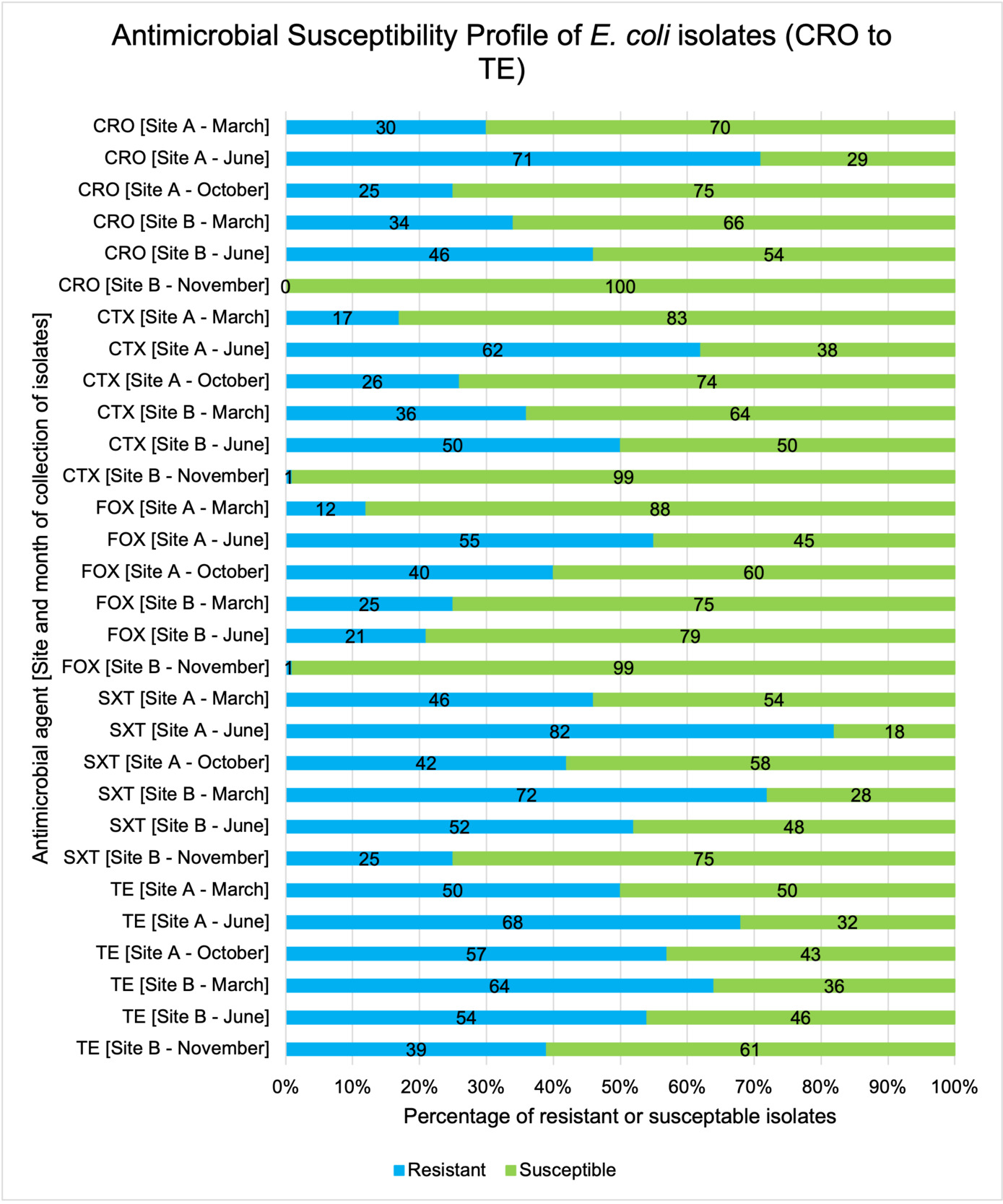

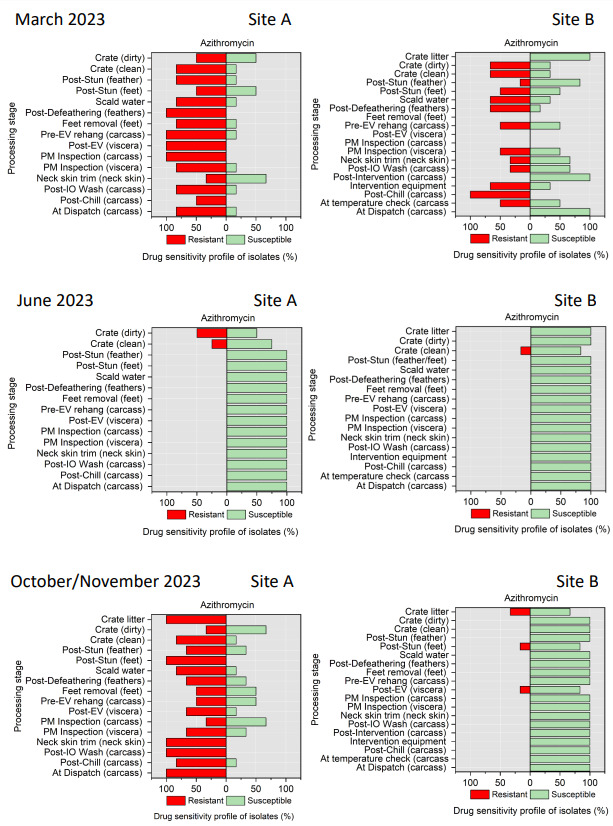

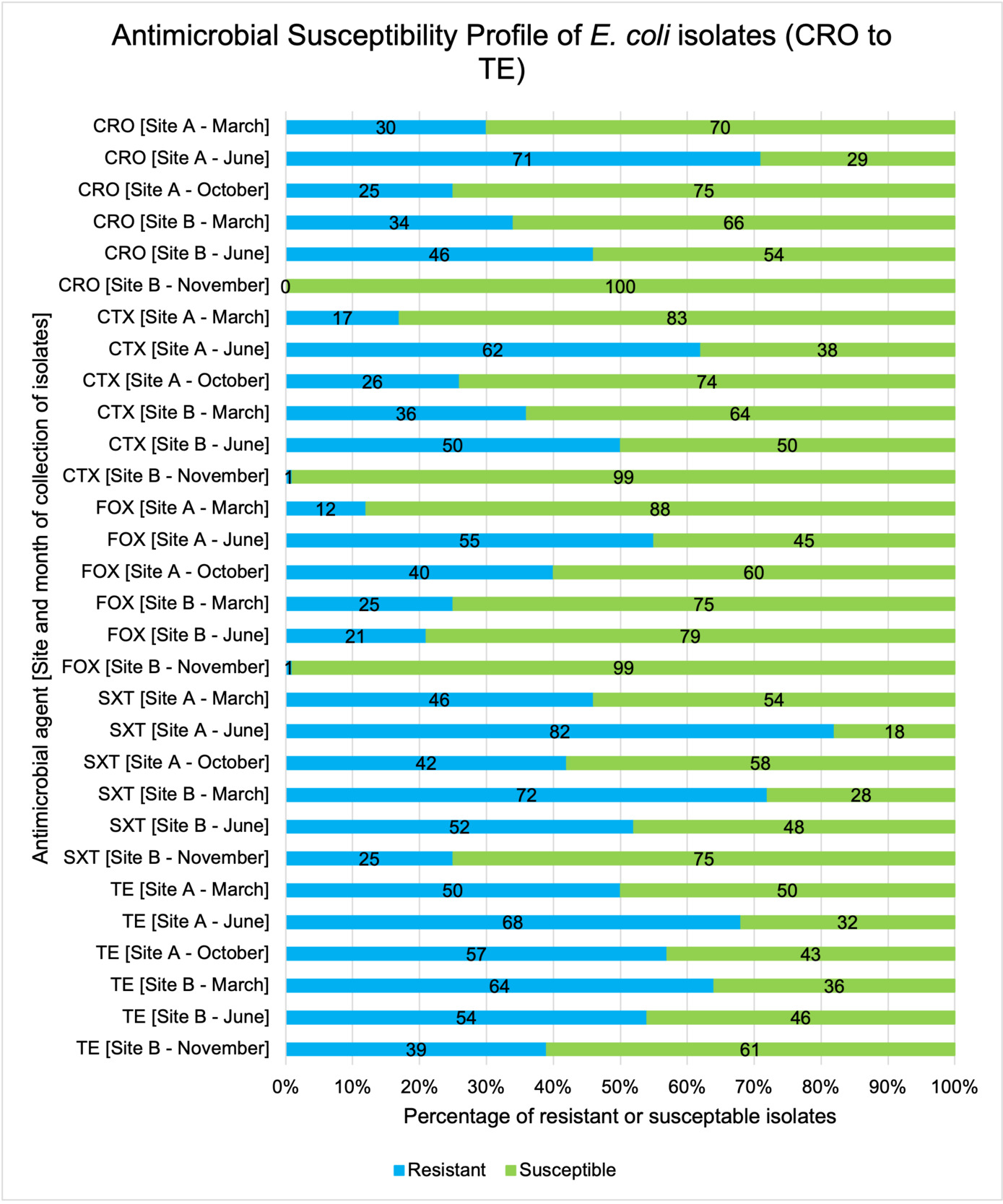

The resistance of Campylobacter spp. isolates to 5 antimicrobial agents were tested and E. coli isolates were tested against 11 antimicrobial agents. Of the Campylobacter spp. isolates, we recorded the highest overall percentage resistance to tetracycline (53%) and lowest overall percentage (7%) resistance to erythromycin. For E. coli isolates, we recorded the highest overall percentage resistance to ampicillin (80%) and lowest overall percentage (13%) resistance to chloramphenicol.

-

Approximately 7% of the Campylobacter jejuni isolates were resistant to three or more classes of antimicrobial (tested against examples of four different classes).

-

Approximately 60% of the E. coli isolates were resistant to three or more classes of antimicrobial (tested against examples of eight different classes).

-

Analysis of the genetics of cultured C. jejuni and E. coli isolates (using whole genome sequencing [WGS]) showed that both C. jejuni and E. coli isolates tested were genetically diverse across sampling points and periods. However, E. coli displayed greater variability in sequence types (STs). In total, 5 C. jejuni STs (3 recognised) and 40 E. coli STs (36 recognised) were identified.

-

Four C. jejuni STs (21, 262, 5136, 6175) were identified across sites, with ST 6175 being most prevalent. All STs isolated carried resistance genes for ampicillin or tetracycline, and a gyrA gene mutation conferring resistance to ciprofloxacin and nalidixic acid.

-

E. coli isolates from both sites showed high genetic diversity with 36 distinct STs identified. Prevalent STs included 10, 155, and 6448. Isolates carried multiple resistance genes and plasmids (genetic elements that can transfer genes between different organisms), with blaTEM and tet(A) genes being common. Plasmid types varied across sampling periods, with Col156, Inc1-l(Alpha), and P0111 being frequently observed.

-

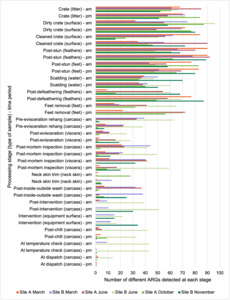

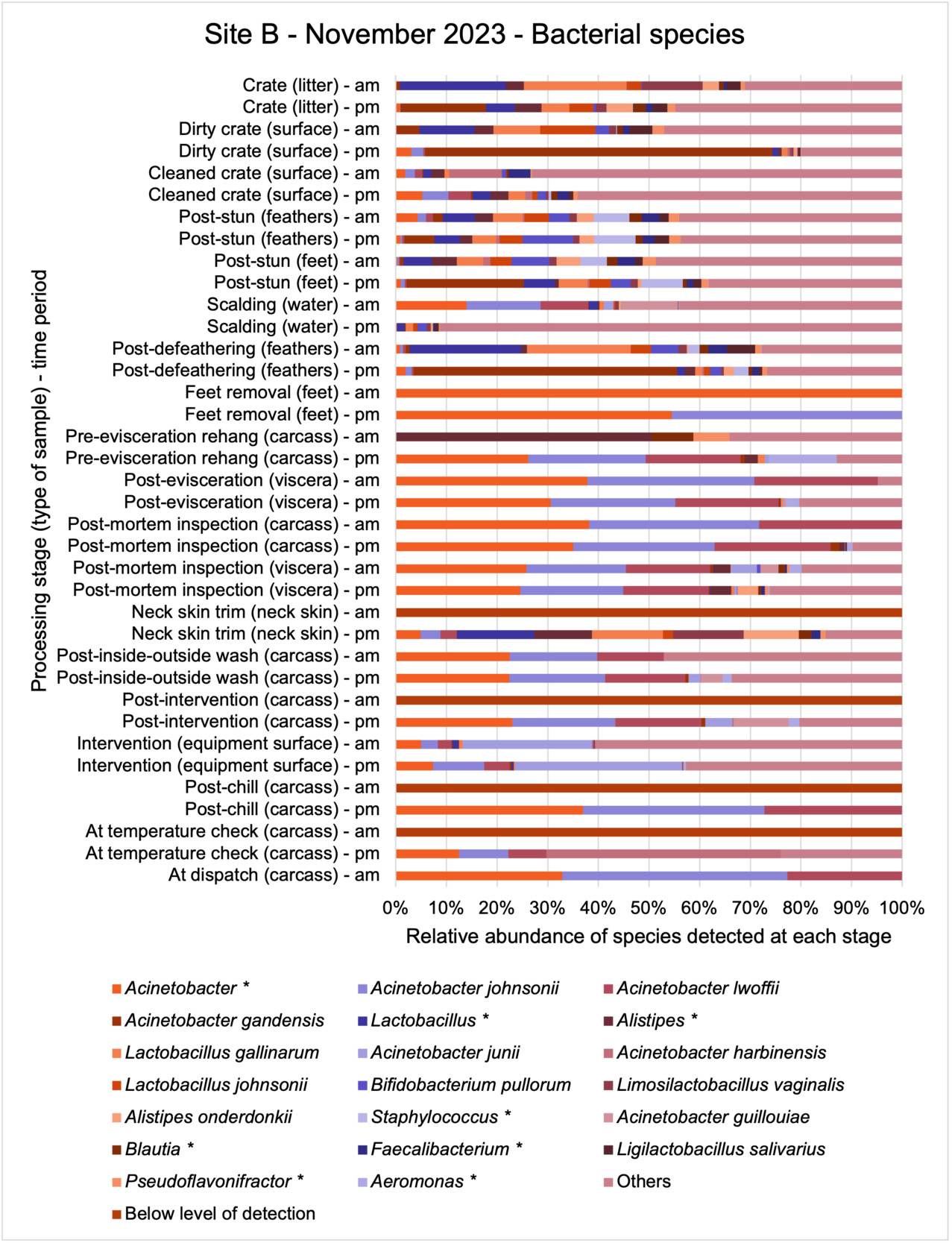

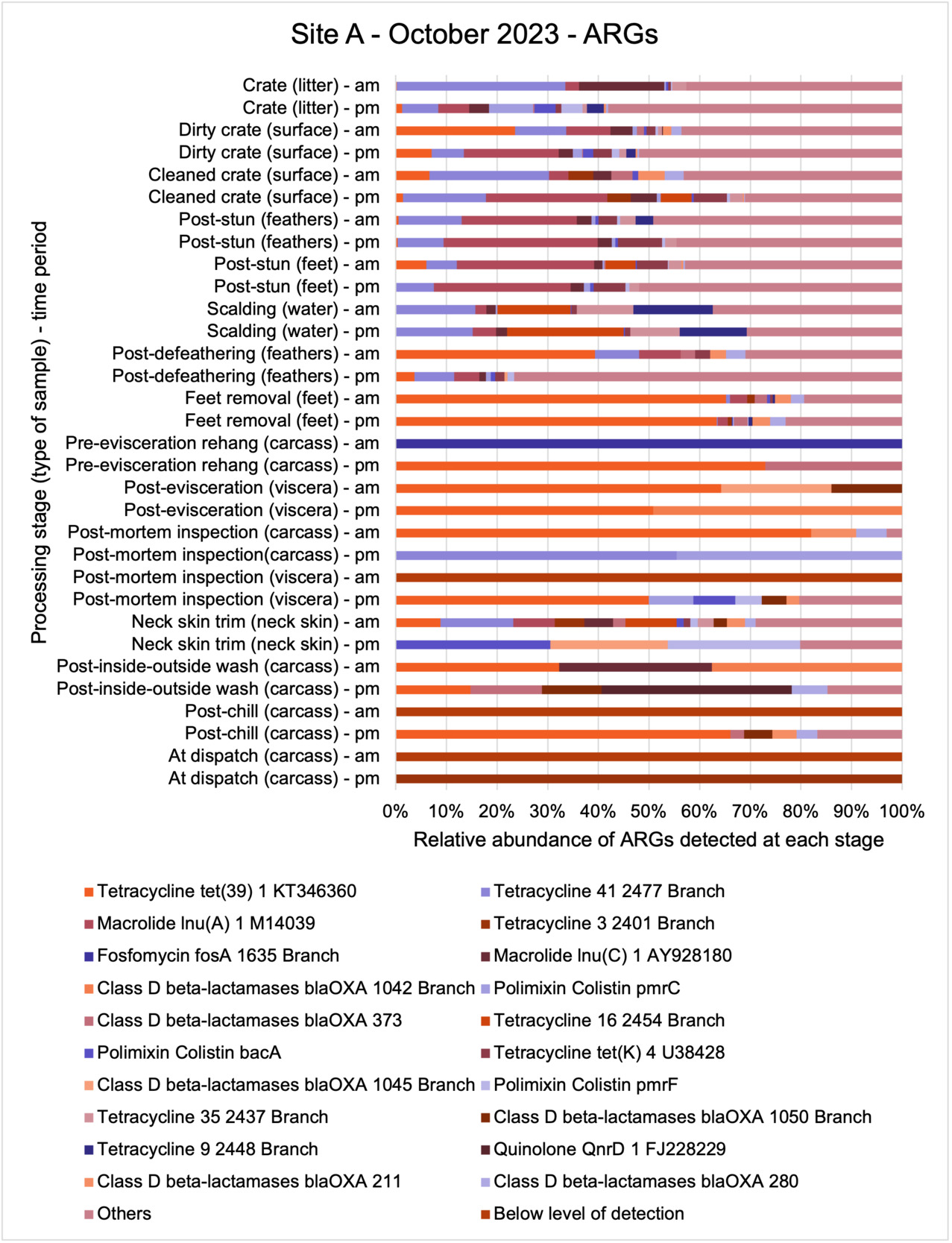

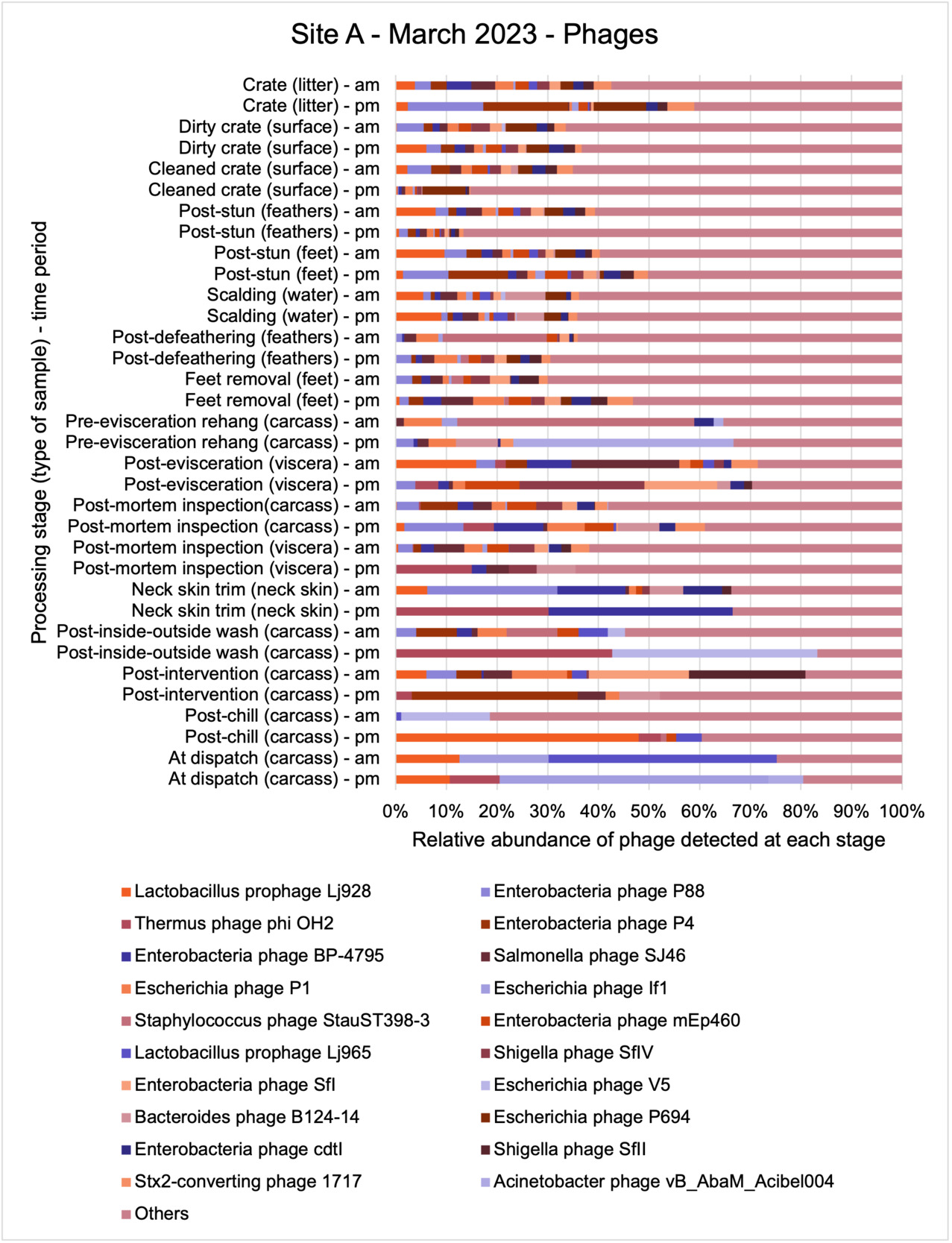

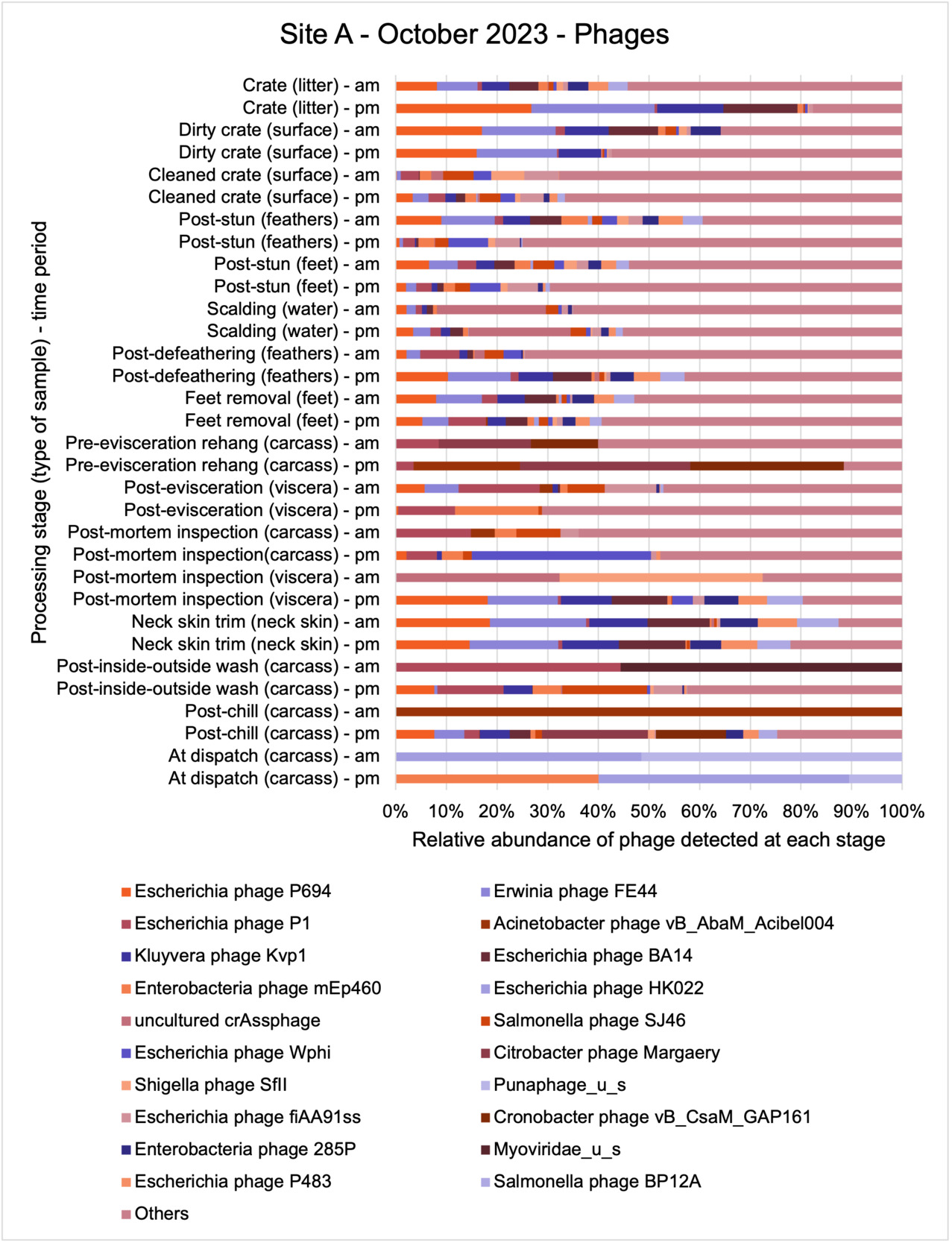

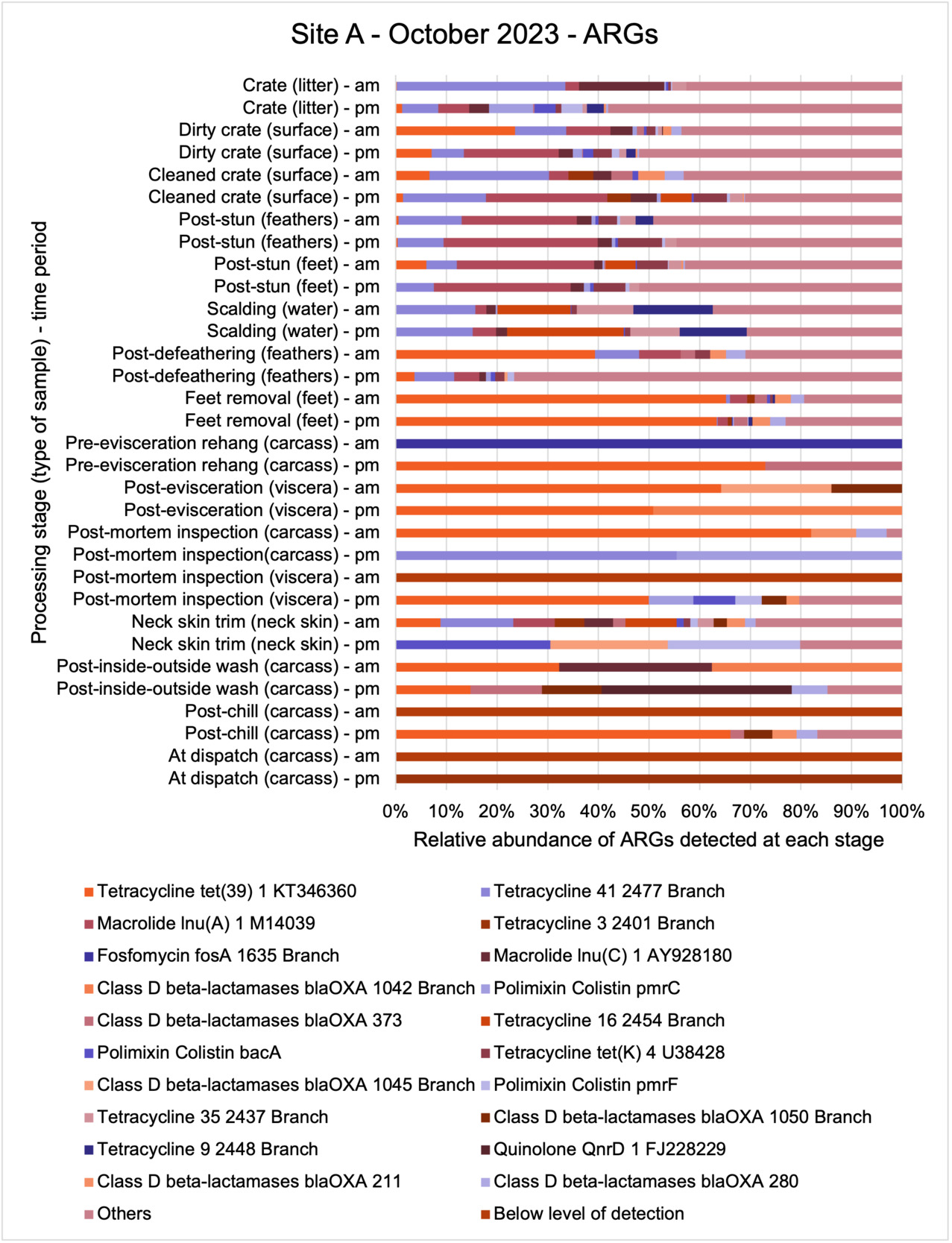

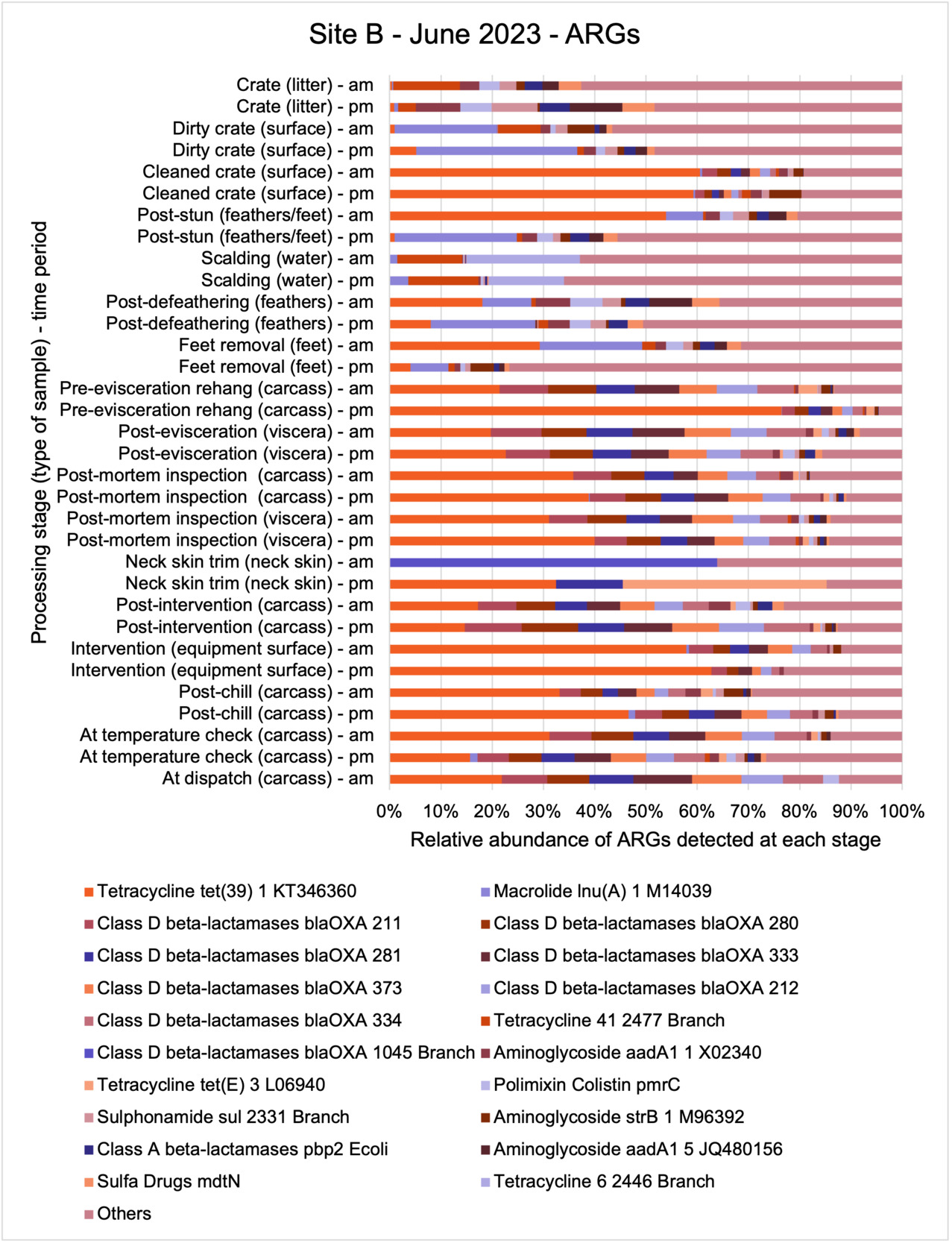

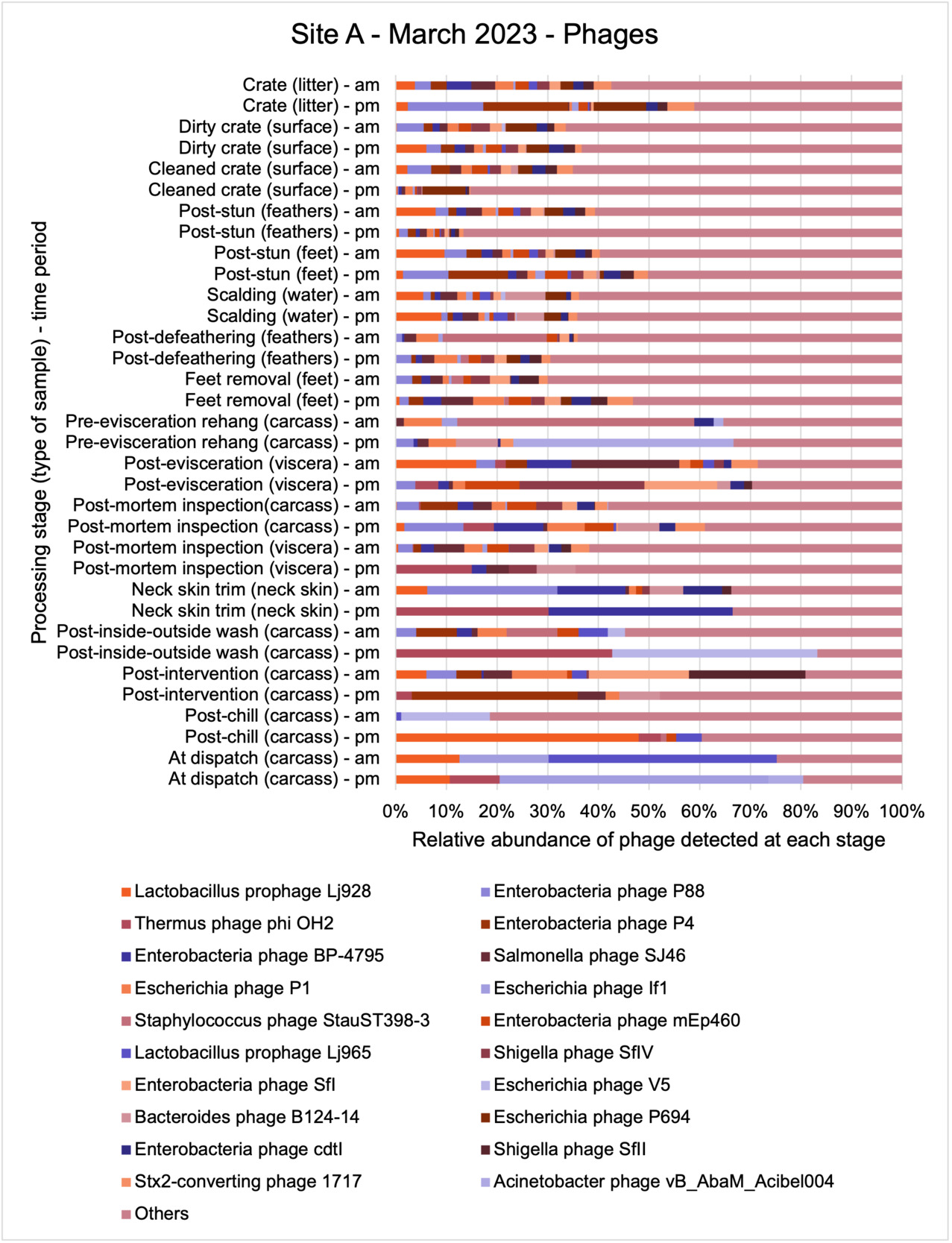

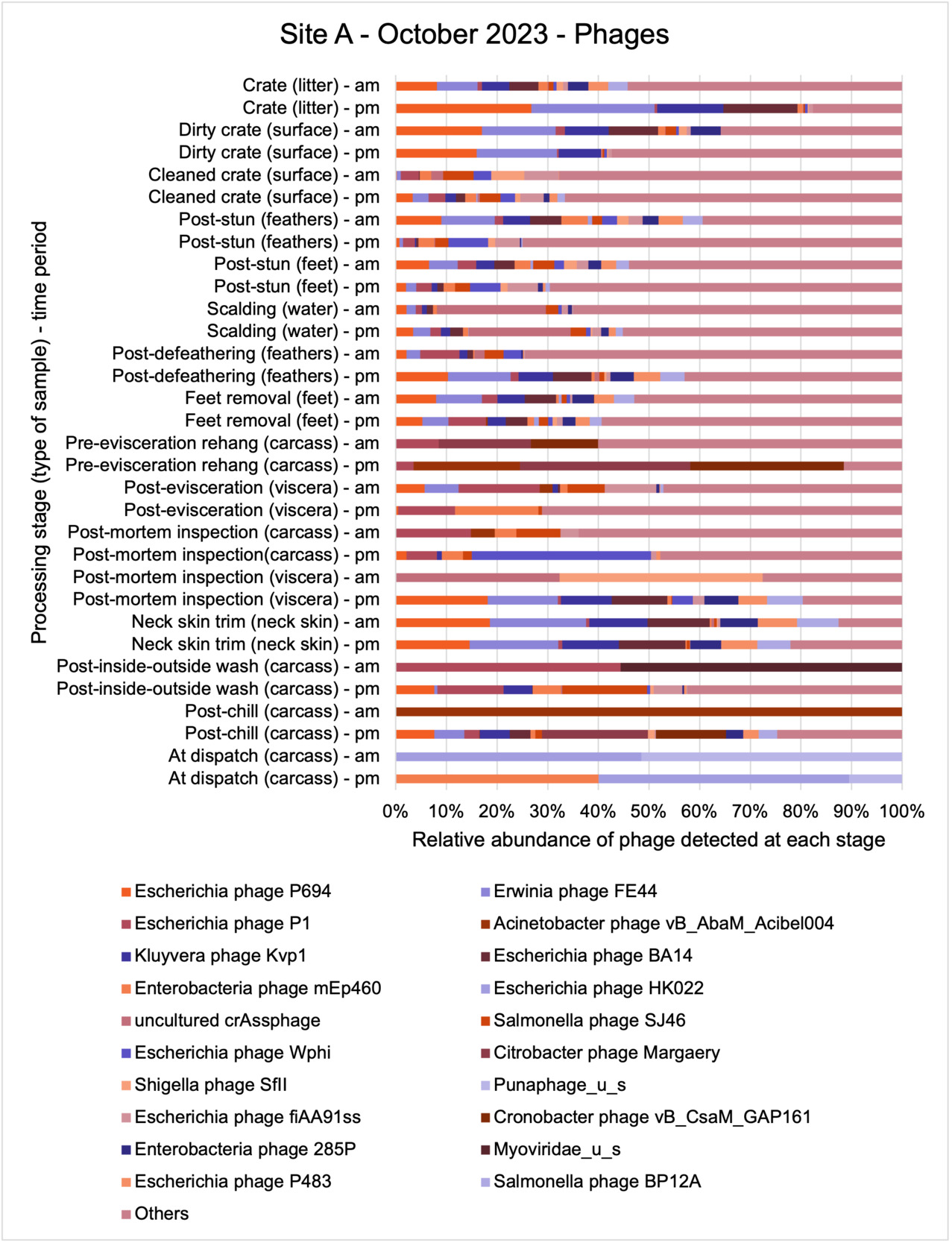

An analysis of samples taken at different processing stages using shotgun metagenomic sequencing (which detects DNA from all organisms within a sample) showed a wide diversity of bacteria, ARGs, and bacteriophages (naturally occurring viruses than target bacteria, usually called phage) present at both poultry sites on the different sampling periods.

-

Overall, there were similarities in the composition of the microbiomes at both sites, though there were some differences in the overall diversity (number of different bacteria, ARGs, or phage) between both sites and some seasonal differences (though mainly only at one site).

-

Interestingly, the most abundant bacteria, ARGs, and phages were the same (though not always in the same order) at both sites and prevalent throughout processing. However, the overall diversity (number) of different bacteria, ARGs, and phages present at different processing stages reduced during processing at both sites.

Overall conclusions

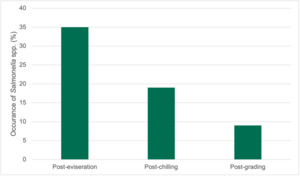

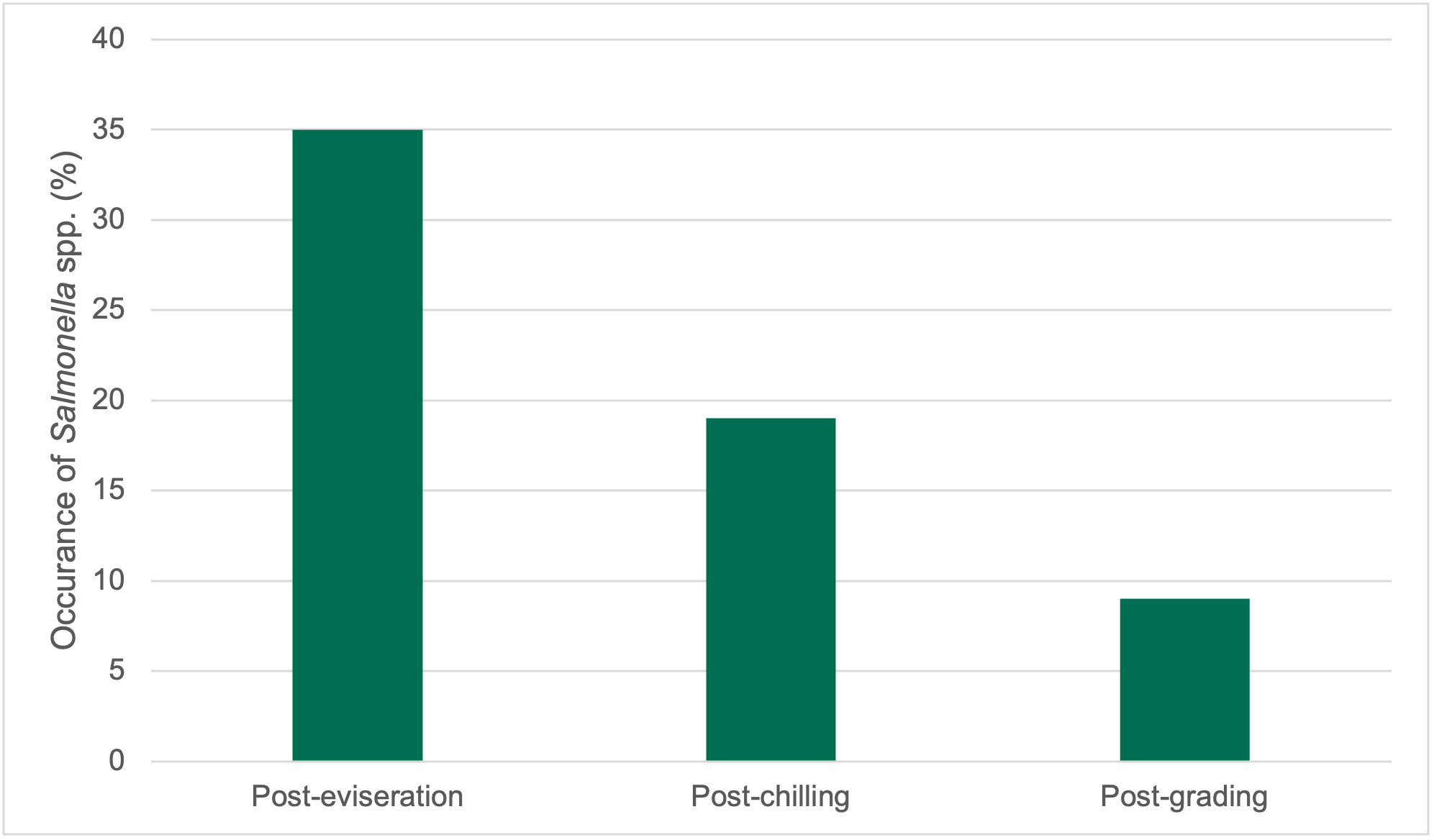

Combining traditional culture methods with modern genomics dependent on DNA sequence analysis of bacteria and ARGs, we created a detailed map of bacterial and gene presence in the poultry processing units under investigation. Our findings using traditional methods showed that while target bacteria like Campylobacter spp. and E. coli were initially present in birds entering the plants, their presence and numbers significantly decreased along the poultry processing line especially following specific procedures such as defeathering and evisceration (internal organ removal). The prevalence of Campylobacter spp. was generally lower than E. coli overall in the samples collected. Specifically, only 65.1% of the total samples from various stages tested positive for the presence of Campylobacter spp., whilst 95.6% of total samples were positive for E. coli.

Antimicrobial resistance testing revealed varying patterns among Campylobacter spp. and E. coli isolates. Campylobacter spp. showed highest resistance to tetracycline (53%) and lowest to erythromycin (7%), while E. coli exhibited highest resistance to ampicillin (80%) and lowest to chloramphenicol (13%). Notably, 7% of Campylobacter spp. and 60% of E. coli isolates were resistant to three or more antimicrobial classes, indicating multidrug resistance (MDR), particularly in E. coli.

Genetic analysis via WGS revealed diverse C. jejuni and E. coli isolates across sampling points. Five C. jejuni STs were identified, with ST 6175 most prevalent, all carrying resistance genes. E. coli showed higher diversity with 36 STs, commonly carrying blaTEM and tet(A) genes. Various plasmid types were observed in E. coli isolates. Genomic analysis of parallel samples confirmed reductions in bacterial and associated ARG diversity through the processing chain, suggesting that the hygienic measures implemented during the poultry processing stages can effectively reduce both bacteria and ARGs. The fate of some resistant bacteria appears less certain and for reasons unknown persist throughout the poultry processing stages. It should be noted that this study is based on only two large scale UK chicken processing plants and may not be a reflection of all chicken processing plants in the UK. Further studies are needed to confirm these results and assess the role of poultry products in spreading AMR/ARGs of concern to human health.

Executive Summary

The overall aim of this project was to access the impact that processing has on the presence and transfer of antimicrobial resistant Campylobacter spp. and E. coli and their associated genes on chicken meat. There is a growing concern that some AMR transmission to humans occurs via the food chain and food processing environments and that these could act as potential hotspots for AMR acquisition and spread. However, relatively little is known about the role of the food chain in the transmission of AMR bacteria, including the transmission and prevalence of AMR bacteria in chicken and chicken products before retail. Since poultry accounts for half of the meat eaten in the UK (BPC, 2018) it represents potentially a significant reservoir for AMR.

Key findings

Although only few studies have focused on the transmission of AMR bacteria or genes during poultry processing, existing research suggests that AMR and ARGs in incoming birds are primarily influenced by farm-level factors rather than in-plant operations leading to cross contamination. There is very limited evidence on the sequential transmission of AMR bacteria and genes during chicken slaughter or the persistence of AMR bacteria and genes in the processing environment. While some studies indicate that ARGs can persist in processing environments and contribute to cross-contamination, the evidence is scarce. Additionally, the impact of cutting operations and physical interventions such as steam on AMR or ARGs in UK plants remains largely unexplored.

This study took samples along the processing chain of two similar sized large scale UK chicken processing sites producing whole chickens and chicken meat for major UK retailers on 3 occasions during the year (March, June, and October/November).

In this study of 376 samples from most stages of poultry processing plants, overall, 65.1% were positive for Campylobacter and 95.6% for E. coli. Levels of Campylobacter spp. ranged from 1.00±0.0 to 3.9±0.5 Log10 CFU/sample, while E. coli levels ranged from 2.0±0.0 to 8.3±0.2 Log10 CFU/sample, with chicken litter (pre-processing stage) showing the highest levels for both bacteria. Both organisms were detected at various processing stages in both plants, with higher counts in earlier stages. Some processing stages yielded no detectable Campylobacter spp. or E. coli in either plant. Interestingly, Campylobacter spp. levels decreased from samples along the processing stages, to non-detectable levels while E. coli, although showing a general decrease, remained detectable in samples from later processing stages.

Out of testing against 5 antimicrobial agents, Campylobacter isolates showed the highest overall resistance to tetracycline (53%) and the lowest overall percentage (7%) to erythromycin. For E. coli isolates, tested against 11 antimicrobial agents, the highest resistance was observed for ampicillin (80%) and the lowest overall percentage for chloramphenicol (12%). MDR was observed in approximately 7% of Campylobacter spp. isolates and 60% of E. coli isolates.

WGS analysis of C. jejuni and E. coli isolates revealed genetic diversity across sampling points and periods, with E. coli showing greater variability in sequence types (STs). Five C. jejuni STs, including ST 6175, which was most prevalent, were identified, all carrying resistance genes for ampicillin or tetracycline, as well as a gyrA mutation conferring resistance to ciprofloxacin and nalidixic acid. E. coli isolates demonstrated high genetic diversity with 36 distinct STs identified, including STs 10, 155, and 6448, carrying multiple resistance genes and plasmids, the resistance genes blaTEM and tet(A) being common. Plasmid types varied across sampling periods, with Col156, Inc1-l(Alpha), and P0111 frequently observed.

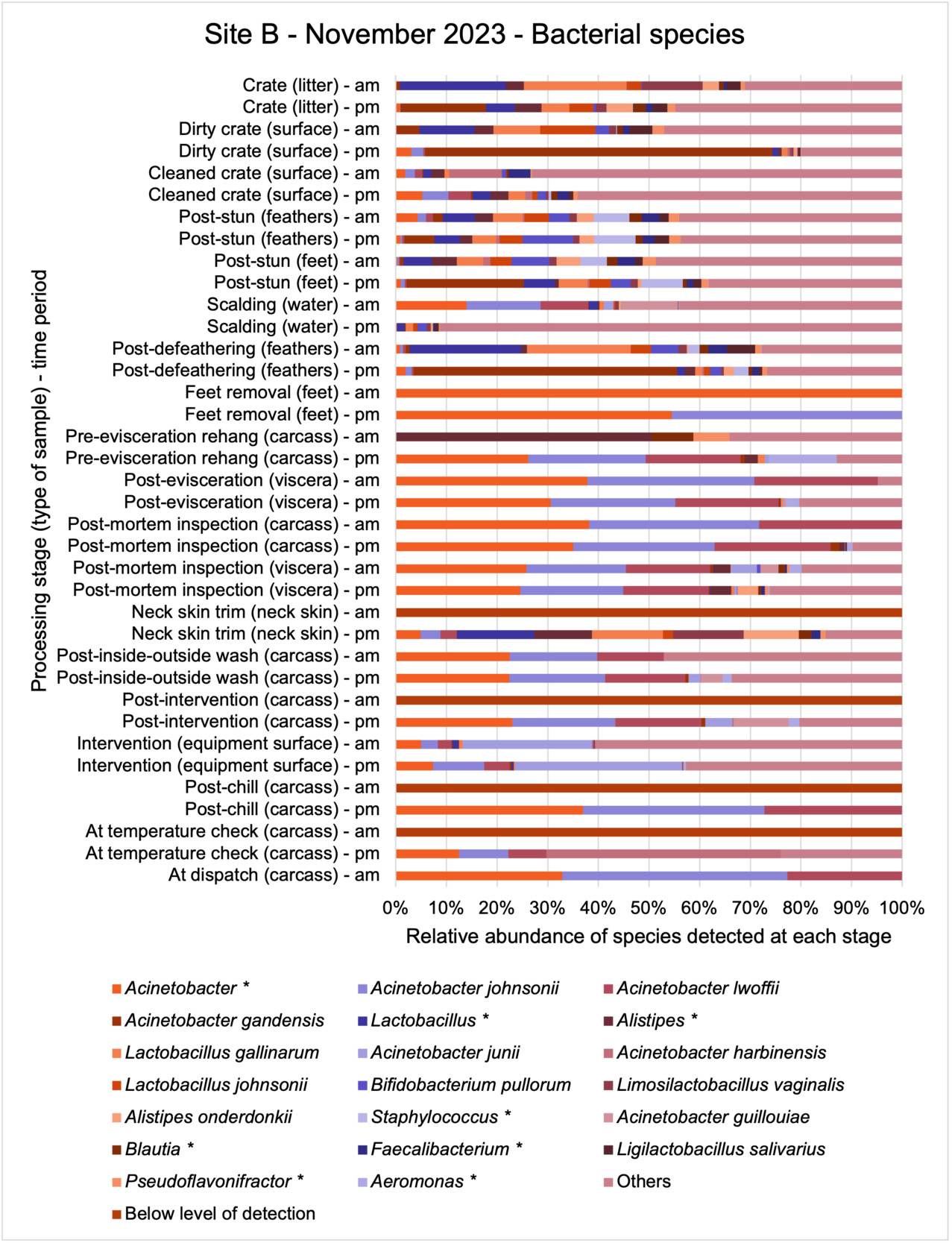

The shotgun metagenomics sequencing identified a diversity of bacteria, ARGs, and phages present across the processing lines at both sites. The results showed a wide diversity of bacteria, ARGs, and phages to be present at both sites on the different sampling periods, many of which only occurred on the individual sampling occasions. However, not surprisingly, there were similarities in the dominant composition of the bacteria, ARGs, and phages at both sites, though there were differences in the overall diversity between both sites and some seasonal differences (though many only at one site). The most abundant phyla were Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, and Actinobacteria, which accounted for the majority of detected phyla in all samples. These same phyla have been reported to be the most abundant phyla in poultry in other studies in other countries (though not always in the same order). Acinetobacter spp. were the most abundant species at both sites, particularly A. johnsonii, lwoffii, and gandensis, and were detected in samples from sampling points along the whole processing chain (from entry to dispatch) at both sites.

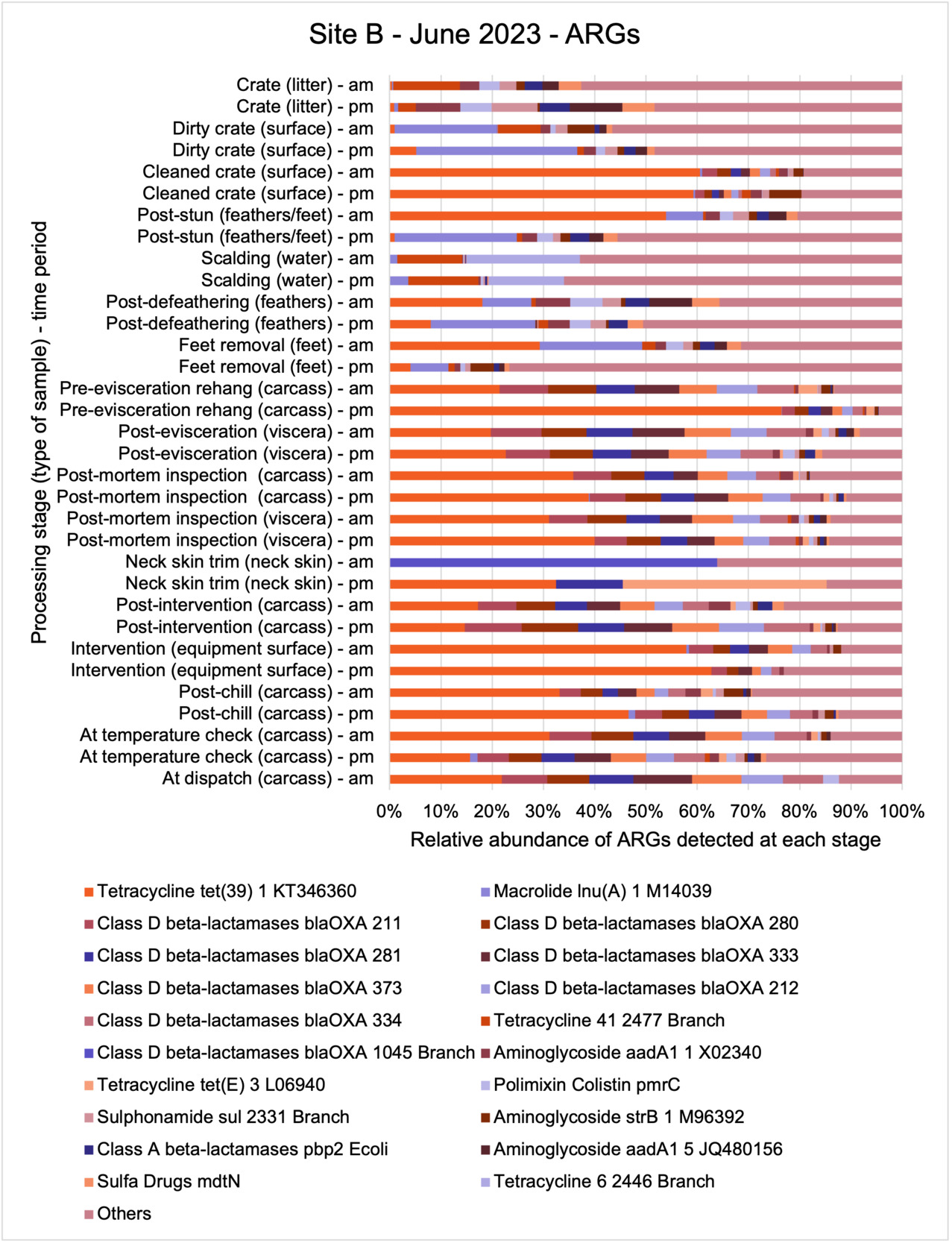

The results from the metagenomics revealed the occurrence of a total of 442 different ARGs which may be involved in resistance to 16 different classes of antimicrobial agents. The most abundant and commonly occurring ARGs in both plants were genes coding for tetracycline resistance. This study also detected the prevalence of phage which could play an important role in the transfer of ARGs within the microbiome or processing environment since they can be associated with the transduction of genes, including ARGs. The overall diversity of bacterial phyla, target bacteria, ARGs, and phages were clearly shown to reduce during processing at both sites. Similar reductions in the diversity of the microbiome through the poultry processing chain have been observed in limited other studies of the poultry processing environment carried out in other countries.

Conclusion and recommendation

The classical approach of traditional culture of the target pathogens combined with powerful genomic analysis allowed us to provide a detailed map of spatial and temporal distributions in the process chain of a working poultry environment. We were able to conclude that the target organisms were readily recovered from the process chain at early stages but following several identified processing stages reduced numbers of Campylobacter spp. and E. coli were recovered. Parallel sampling for genomic analysis demonstrated extensive bacterial diversity from early stages of the process which was concordant with associated ARG diversity. The loss of ARG diversity following specific interventions in the process chain suggests that ARGs along with their host bacteria may also be reduced by the interventions. However, some ARGs may persist because they are carried by particularly resilient bacteria to dispatch. We should consider whether these results can be repeated and are representative of other UK processor operations and to what extent poultry products represent a significant reservoir for AMR/ARGs. Further studies are needed to clarify if the microbiome composition and changes in diversity observed in our study are representative of other UK-wide poultry plants.

This study (in common with others) shows that shotgun metagenomic sequencing of processing environments is an appropriate approach to investigate how microbiome composition and diversity changes during processing and provide insights not provided by traditional microbiological analysis. However, such approaches also result in large data sets which are slow to acquire and must be carefully analysed and interpreted. As a result of metagenomic analysis, this study detected extensive phage presence in most samples. Phages have been associated with the transduction of genes (including ARGs) which could play a role in the transfer of ARGs within the poultry microbiome, but whether this occurs within the poultry processing environment is unknown and requires future work to establish baseline data.

It is vital that future work focuses on elucidating hygiene/contamination processes/interventions in processing chains, and which have the greatest influence on the reduction of target microbes, phages, and ARGs, thus allowing for improved targeted interventions to better manage these microbial populations to benefit environmental and public health.

1. Introduction

For the interpretation of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) in this study, the WHO definition will be applied (WHO, 2018): “Antimicrobial resistance is resistance of a microorganism to an antimicrobial drug that was originally effective for treatment of infections caused by it.” AMR is a complex issue driven by a variety of interconnected factors enabling microorganisms to withstand the killing or static effects of antimicrobial agents, such as antibiotics, antifungals, antivirals, disinfectants, preservatives. Microorganisms may be inherently resistant to such agents or can change and adapt to overcome the effects of such agents. Microorganisms can acquire antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) through mutation or by obtaining foreign DNA from other microorganisms, with the widespread use of antimicrobial agents particularly driving the selection for AMR.

According to the British Poultry Council (Maxwell, 2020), the UK poultry meat sector has achieved a 76% reduction in total antimicrobial drug use and a 97.3% reduction in the use of critically important antimicrobials (CIA) over the past seven years (2012-2019). Additionally, UK Veterinary Antibiotic Resistance and Sales Surveillance 2022 Report (UK-VARSS, 2023) reported a 57% reduction in overall antimicrobial drug sales for animals and an 81% reduction in sales of high-priority CIAs for all animals in 2022 compared to 2014. Specifically, antimicrobial usage (AMU) in broilers and turkeys decreased by 71% and 84%, respectively, with a 99% reduction in high-priority CIAs for meat poultry in 2022 compared to 2014.

However, the reduction of AMU alone may not be sufficient to control AMR because the environmental persistence and spread of AMR bacteria and ARGs is a major contributory factor (Koutsoumanis et al., 2021). As highlighted in a recent EFSA biohazards panel report (Koutsoumanis et al., 2021), apart from prudent AMU, the most important measures to mitigate AMR applicable for all the food-production sectors investigated, both at pre- and post-harvest, involve the correct implementation of effective well known general management measures (good hygiene practices, biosecurity) to prevent/reduce occurrence and transmission of pathogens and other microorganisms. Identifying activities at food processing stages that cause or prevent the spread of AMR bacteria and ARGs in the different production sectors is an important priority for intervention. Since AMR bacteria are primarily associated with gut microbiota, reducing the likelihood of introduction, spread, and persistence of faecal contamination during meat processing is a high priority.

Contamination and control pathways for AMR bacteria in the chicken food chain include: metaphylactic administration of antimicrobial drugs to poultry, biosecurity in the growing sheds; cross-contamination in growing sheds, contamination or control via feed and water, cross-contamination during thinning, cross-contamination during transport to abattoir, control through washing of transport crates, cross-contamination during abattoir operations (slaughter, bleeding, scalding, defeathering, evisceration, cutting and portioning), potential control/reduction during abattoir operations (such as hard scalding, inside-outside wash, pre-chill interventions, chilling, freezing), packaging, control during chilled and frozen storage, distribution, retail display, consumer storage etc. (Bennani et al., 2020; Hedman et al., 2020). A recent EFSA biohazards panel report (2021), highlighted the role of contaminated process water and workers, through their hands or equipment, as sources of AMR bacteria. In 2020, the Food Standards Agency published a literature review on the impact of secondary processing of meat and meat products, but while that covered secondary processing of poultry (i.e. post primary chilling) it did not cover primary processing operations. The review concluded that there was a lack of studies examining whether persistently colonised processing environments can act as a contamination source for AMR bacteria as most of the literature concerns AMR in retail meats.

Campylobacter spp. are considered as priority pathogens due to their widespread antimicrobial resistance (Halaby et al., 2013). These bacteria are a common cause of foodborne illnesses and are frequently found in poultry and other food-producing animals (Havelaar et al., 2015). The increasing prevalence of antimicrobial resistant Campylobacter strains poses a significant threat to public health and food safety (Qin et al., 2023). Due to the importance of Campylobacter spp. in public health and its rising resistance to antimicrobials, particularly fluoroquinolones, Campylobacter spp. have been recognised as one of the serious antimicrobial-resistant threats of high priority by both WHO and the CDC [US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] (Tacconelli et al., 2018).

Since E. coli is ubiquitous in the gastrointestinal tract of warm-blooded animals, it has been extensively used to monitor AMR in food animals (including chicken). Over the past few decades, AMR has increased at a faster rate among chicken isolates of E. coli than human clinical isolates (Tadesse et al., 2012). This trend is alarming as it highlights the role of poultry production in the dissemination of AMR (Bhattarai et al., 2024), which can be transmitted to humans through the food chain. E. coli strains in poultry are increasingly resistant to multiple classes of antimicrobial, including those critical for human medicine, such as fluoroquinolones and third-generation cephalosporins (Fenollar-Penadés et al., 2024).

The rise of MDR E. coli and antimicrobial resistant Campylobacter spp. in poultry presents a complex challenge for both animal and human health. This situation highlights the critical importance of comprehensive AMR surveillance and responsible antimicrobial use in agriculture. Also, while overall antimicrobial use has decreased (UK-VARSS, 2023), the persistence and, in some cases, increase of resistant bacteria emphasises the need for continued vigilance and action across the agricultural and public health sectors.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in bacterial pathogens is intensified by the frequent role of mobile genetic elements (MGEs). The transfer of ARGs within and between different species of bacteria is commonly facilitated by MGEs, although the important role of individual plasmids and bacteriophages is not entirely understood.

The detection and identification of lytic or lysogenic bacteriophages (phages) from poultry environments at scale by metagenomic sequencing is an emerging area of interest. To what extent the diversity and epidemiology of phages in poultry processing and the natural environment is important however is yet to be determined. Phages can be present in large numbers especially from contaminating faecal matter and the transfer of ARGs by genes from bacteria to bacteria with specific phage can be demonstrated at least in the laboratory. In ‘real world’ microbial ecology with poultry, multiple compounding factors make it difficult to provide conclusive evidence that transfer of ARGs by phages occurs in this environment.

Although the FSA has been monitoring the prevalence and types of AMR bacteria in retail chicken, there is strong evidence that commensal and pathogenic AMR bacteria can be found on poultry meat. However, what is not known at present, is the role that chicken processing has on the prevalence and spread of AMR bacteria. It is also unclear whether persistently colonised processing environments can act as a contamination source for AMR bacteria, thus showing the importance of environmental monitoring and identification and survey of biofilms. There is a need to evaluate the impact of processing steps used during chicken production and the processing environment on the (molecular) epidemiology and transmission of AMR in chicken meat, to identify probable pathways for transmission, and mitigate the risks of transmission.

1.1. Aims and objectives of this project

The overall aim of this project was to assess the impact that processing has on the presence and transfer of antimicrobial resistant Campylobacter spp. and E. coli and associated ARGs on chicken meat.

The project was carried out in two parts with an initial literature review carried out to aid the project sampling plan/design (see Appendix). A detailed field and laboratory study was then conducted to assess the abundance and potential transmission of antimicrobial resistant Campylobacter spp. and E. coli during the processing of chicken in two similar large scale intensive UK slaughterhouses.

The specific objectives set for the “field” and laboratory study were to determine:

-

The presence and abundance of Campylobacter spp. and E. coli cultured from samples taken at different stages along the chicken processing line at different sampling periods.

-

The AMR profiles in Campylobacter spp. and E. coli isolates recovered from samples taken at different stages along the chicken processing line using Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST).

-

The presence and types of ARGs present in selected individual isolates of E. coli and Campylobacter spp. using WGS.

-

The diversity and abundance of bacteria, ARGs, and bacteriophages (naturally present viruses that target bacteria, commonly called phages) at different stages along the chicken processing line by modern genomic technology (metagenomic sequencing).

2. Materials and Methods

The project was carried out in two parts. Part 1: an initial literature review was carried out to aid the project sampling plan/design (detailed in the Appendix) and Part 2: a field and laboratory study carried out to assess the presence and potential transmission of antimicrobial resistant Campylobacter spp. and E. coli during the processing of chicken in two similar large scale intensive UK slaughterhouses and cutting plants.

2.1. Field and laboratory sampling and analysis

This section details the sample locations and collection procedures at two UK slaughterhouses and cutting plants over three distinct periods. Samples, including swabs, liquids, and neck skin, were collected from various stages of poultry processing. Using traditional microbiological methods, each sample was analysed for the presence, levels and AMR characteristics of Campylobacter spp. and E. coli isolates. WGS was then performed on selected individual isolates to evaluate the presence of ARGs. Additionally, pooled samples from each processing stage were selected and subjected to shotgun metagenomic analysis to enable the assessment of microbial diversity, bacteriophage diversity, and ARG distribution across the different processing stages.

2.1.1. Sampling location and sampling dates

Two slaughterhouses in the UK were selected as sampling locations for this study. One of the plants was located in the East Midland region and the other in the West Midland region of England, thus representing different geographical areas within the UK. Both of the sites were large scale chicken processing plants with similar processing lines but with differences in factory layout, some equipment, and distances between individual processing stages. Both supply major UK retailers with chicken and had similar throughputs and line speeds, though Site A was slightly larger than Site B in terms of throughput and ran at a faster line speed. Table 1 below shows details of the 2 sites visited for sample collection in this project. Each site was visited on 3 occasions in 2023. An initial in-field sampling occurred in March 2023 (16th March for Site A and 14th March 2023 for Site B; referred to as March in this report). Two further sampling visits occurred in the summer and winter months. For the summer collection, samples were collected in June 2023 (21st June 2023 for Site A and 27th June for Site B; referred to as June in this report) and October and November 2023 (18th October for Site A and 21st November for Site B; referred to October and November respectively in this report). At each site on each visit samples were collected in the morning (am) and afternoon (pm) at each different processing stages.

Table 1.Details of the two chicken processing sites visited for sample collection in this project.

| Details |

Site A |

Site B |

| Number of birds processed per day |

400,000 birds/day (Monday – Thursday); 200,000 birds/day (Friday and Saturday) |

320,000 birds - 370,000 birds per day across 2 shifts |

| Approximate line speeds (birds per minute [bpm]) |

217bpm |

175bpm |

| Number of lines |

2 |

2 |

| Chicken source |

Company/contracted Red Tractor Assurance (RTA) farms in the UK |

Company/contracted Red Tractor Assurance (RTA) farms in the UK |

| Number of farms supplying birds on March visit |

6 |

7 |

| Number of farms supplying birds on June visit |

5 |

6 |

| Number of farms supplying birds in October/November visits |

7 |

7 |

| Distance between supplying farms and site on March visits (miles) |

8 to 45 (mean 23) |

25 to 90 (mean 61) |

| Distance between supplying farms and site on June visits (miles) |

8 to 28 (mean 18) |

5 to 113 (mean 82) |

| Distance between supplying farms and site on October/November visits (miles) |

7 to 39 (mean 21) |

9 to 96 (mean 50) |

| Additional details |

Different farms supplied chickens to Site A on each of the visits. But one of the farms that supplied Site A in March also supplied Site B in June. Also, one of the farms that supplied chickens to Site A in June also supplied chickens to Site B in November. |

Two of the farms supplying chickens to Site B in March also supplied chickens to Site B in June. Two different farms that supplied chickens to Site B in March also supplied chickens to Site B in November. None of the farms that supplied chickens to Site B in June supplied chickens to Site B in November. |

2.1.2. Description of chicken processing and sampling stages

At both sites, live birds were transported from the farm in crates, on arrival at the processing plants the birds were gas stunned rendering them unconscious. They were then removed from the crates by hand and suspended by their feet on a moving line, the birds were then euthanised and bled. The crates were cleaned and disinfected before being returned to the farms for use. After slaughter, birds entered a process where their feathers were removed. This began by putting the birds through a bath of hot water, which is designed to help loosen feathers, a processing stage called scalding. Feather removal (a processing stage called defeathering) was then performed by a machine called a “picker,” which includes hundreds of little rubber “fingers” that rotate around to remove the feathers. In Site A the heads were removed after defeathering, while in Site B the heads were removed prior to scalding. After the feathers were removed the feet were removed and the whole carcass inspected, and the carcasses then rehung on a separate moving line. The carcasses were then sent to an “eviscerating” (EV) line which removed the internal organs (viscera) in a series of operations. After the organs were removed, each carcass and the separated viscera were inspected (post-mortem (PM) inspection). After inspection excess neck skin was trimmed from the carcasses before the inside and outside of the carcass is washed in a machine called an “inside-outside (IO) washer”. In both of the plants the carcasses then passed through a thermal intervention process designed to reduce bacteria on the carcass prior to chilling (since different processors may use different interventions, or may use interventions in their plants, details of the exact intervention have been withheld in this report to ensure the anonymity of the plants). The same intervention was used in both of the plants. After the intervention the carcasses were chilled in continuous in-line air chillers to lower their temperature before being packed and dispatched. In Site B carcasses were also sampled at an accessible point between exit from the chiller and final dispatch, where an additional in process temperature check was made.

Due to access (for safety reasons not all processing stages were accessible) and scheduling issues (due to distances between sampling points, line speeds, and the time required to sample at different sampling points) samples could not be collected at the same intended sampling points in the plants on all of the visits. The sampling points where samples were collected at each site on each visit is shown in Table 2 and where, what type of sample, and at what time samples were collected on each visit shown in Table 3. These samples consisted of whole chicken carcass swabs (swabbing and sponging covered whole bird carcass surface area as best as possible), neck skin (excised and weight out for analysis), scalding water samples, crate swab (taken from an ~10cm x 10cm area) and equipment surface swabs (covering an ~30cm x 30cm area).

Table 2.Number of sampling points where samples were collected on each visit.

| Details |

Site A March |

Site B March |

Site A June |

Site B June |

Site A October |

Site B November |

| Number of sampling points |

34 |

33 |

32 |

33 |

32 |

37 |

Table 3.Samples collected on each visit.

| Processing stage (type of sample) - time |

Site A March |

Site B March |

Site A June |

Site B June |

Site A October |

Site B November |

| Crate (litter) - am |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Crate (litter) - pm |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Dirty crate (surface) - am |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Dirty crate (surface) - pm |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Cleaned crate (surface) - am |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Cleaned crate (surface) - pm |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post-stun (feathers) - am |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post-stun (feathers) - pm |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post-stun (feet) - am |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post-stun (feet) - pm |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Scalding (water) - am |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Scalding (water) - pm |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post-defeathering (feathers) - am |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post-defeathering (feathers) - pm |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Feet removal (feet) - am |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Feet removal (feet) - pm |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Pre-evisceration rehang (carcass) - am |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Pre-evisceration rehang (carcass) - pm |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post-evisceration (viscera) - am |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post-evisceration (viscera) - pm |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post-mortem inspection (carcass) - am |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post-mortem inspection (carcass) - pm |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post-mortem inspection (viscera) - am |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post-mortem inspection (viscera) - pm |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Neck skin trim (neck skin) - am |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Neck skin trim (neck skin) - pm |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post-inside-outside wash (carcass) - am |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post-inside-outside wash (carcass) - pm |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post-intervention (carcass) - am |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

| Post-intervention (carcass) - pm |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

| Intervention (equipment surface) - am |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

| Intervention (equipment surface) - pm |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

| Post-chill (carcass) - am |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post-chill (carcass) - pm |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| At temperature check (carcass) - am |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

| At temperature check (carcass) - pm |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

| At dispatch (carcass) - am |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| At dispatch (carcass) - pm |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

2.1.3. Sample collection and transportation

Based on discussions with the project team and the sequencing laboratory (CosmosID, an external laboratory) with which we collaborated on this project, we picked a swabbing/sponge method for sample collection, except for neck skin, which was excised at the factory and deposited in a sampling bag for analysis, and water samples (60 ml), which were directly placed in the sampling tube.

2.2. Isolation, enumeration, and confirmation of Campylobacter spp. and E. coli from samples

For Campylobacter spp., recovery and enumeration was carried out in accordance with ISO 10272-2:2017 (direct method) for the detection and enumeration of Campylobacter spp. in chicken meat (applied with a detection limit of 10 CFU per whole carcass, g, or cm3 of sample tested).

Briefly, to prepare the sample for testing, each sponge was rinsed with 10mL of buffered peptone water (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK), and 100 μl of the resulting suspension was then subjected to threefold serial dilutions. From each dilution, 0.333ml was inoculated on modified charcoal cefoperazone deoxycholate agar (mCCDA). The plates were incubated for at least 44 hours at 41.5 ± 1°C under microaerobic conditions created with an Oxoid™ CampyGen™ sachet. The presumptive Campylobacter colonies were then further confirmed by inoculating five identical colonies on Columbia blood agar supplemented with defibrinated sheep blood.

For the enumeration, detection, and identification E. coli, 100 μl of each dilution was inoculated on Tryptone Bile X-glucuronide (TBX) agar consisting of chromogen 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-beta-D-glucuronide (X-glucuronide). Typical E. coli colonies were counted, and their levels were enumerated with a detection limit of 100 CFU) per whole carcass, g, or cm3 of sample tested.

All presumptive bacterial isolates were further confirmed by a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis. Thereafter, all confirmed bacteria colonies were tested against a broad spectrum of antimicrobial classes. All recovered and confirmed bacteria isolates were retained in storage at ambient temperature for use in further analysis (Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST) and Whole-Genome Sequencing [WGS]). Confirmed isolates were also placed in glycerol and stored at -80°C for long term storage.

2.3. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST) of Campylobacter spp. and E. coli isolates

AST of confirmed Campylobacter spp. and E. coli isolates was carried out against a range of different antimicrobial agents (Table 4 and Table 5 respectively) to determine the resistance profile of the isolates.

Campylobacter spp. isolates were tested against ciprofloxacin, tetracycline, streptomycin, erythromycin, and nalidixic acid (Table 4). Minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) values for ciprofloxacin (CIP), erythromycin (E), nalidixic acid (NA), streptomycin (S), and tetracycline (TE) were determined by the microdilution method. This panel was chosen in accordance with EUCAST guidelines and recommendations of the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) (EUCAST, 2023).

All E. coli isolates were tested against amoxicillin + clavulanic acid, ciprofloxacin, ceftriaxone, ceftazidime, cefoxitin, trimethoprim/ sulfamethoxazole, cefotaxime, azithromycin, ampicillin, chloramphenicol, and tetracycline (Table 5) using a disk diffusion method, following guidelines from the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI, 2024).

Table 4.Antimicrobial agents and breakpoints used for AST of Campylobacter spp. isolates.

| Class |

Family |

Antimicrobial Agent (Concentration) |

Breakpoints (μg/mL) |

| Aminoglycosides |

Aminoglycosides |

Streptomycin – S |

≥8 |

| Macrolides |

Macrolides |

Erythromycin – E (15 µg) |

≥16 |

| Quinolones |

Fluoroquinolones |

Ciprofloxacin – CIP (5 µg) |

≥1 |

| Quinolones |

1st generation quinolones |

Nalidixic acid - NA |

≥32 |

| Tetracycline |

Tetracyclines |

Tetracycline – TE (30 µg) |

≥4 |

Table 5.Antimicrobial agents used for AST of E. coli isolates.

| Class |

Family |

Antimicrobial Agent (Concentration) |

| Beta-lactams |

Aminopenicillin |

Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid - AMC (30 µg) |

| Cephalosporins |

3rd generation cephalosporins |

Cefotaxime - CTX (30 µg) |

| Cephalosporins |

3rd generation cephalosporins |

Ceftriaxone - CRO (30 µg) |

| Cephalosporins |

3rd generation cephalosporins |

Ceftazidime - CAZ (30 µg) |

| Cephalosporins |

2nd generation cephalosporins |

Cefoxitin - FOX (30 µg) |

| Cotrimoxazoles |

Sulfonamides-Trimethoprims |

Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole - SXT (25 µg) |

| Macrolides |

Macrolides |

Azithromycin - AZM (15 µg) |

| Penicillins |

Aminopenicillins |

Ampicillin - AMP (2 µg) |

| Phenicols |

Phenicols |

Chloramphenicol - C (30 µg) |

| Quinolones |

Fluoroquinolones |

Ciprofloxacin - CIP (5 µg) |

| Tetracycline |

Tetracycline |

Tetracycline - TE |

2.4. Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) of Campylobacter spp. and E. coli isolates

To predict genetic determinants of antibiotic resistance, WGS was conducted on 107 of the isolates that had been characterised using AST. In total 69 E. coli and 38 Campylobacter spp. isolates were selected and sent for WGS.

2.4.1. Campylobacter spp. and E. coli isolates selected along poultry processing stages chosen for further study.

To better understand the ARGs present in Campylobacter spp. and E. coli genomes, isolates that had shown the highest levels of phenotypic AMR (i.e. resistance to the largest number of antimicrobial agents) characterised using AST were selected for WGS. Details of at what stages Campylobacter spp. and E. coli isolates selected for WGS were collected from Site A and Site B are shown in Table 6 and Table 7, respectively.

Table 6.Stages where Campylobacter spp. isolates were selected for WGS analysis.

| Processing stage (type of sample) - time |

Site A Jun |

Site B Jun |

Site A Oct |

Site B Nov |

| Crate (litter) |

Yes*** |

No |

Yes*** |

Yes |

| Dirty crate (surface) |

Yes** |

No |

Yes** |

No |

| Cleaned crate (surface) |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

| Post-stun (feathers) |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

| Post-stun (feet) |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

| Scalding (water) |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Post-defeathering (feathers) |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes** |

Yes*** |

| Feet removal (feet) |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Pre-evisceration rehang (carcass) |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Post-evisceration (viscera) |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

| Post-mortem inspection (carcass) |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Post-mortem inspection (viscera) |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Neck skin trim (neck skin) |

No |

Yes |

Yes* |

No |

| Post-inside-outside wash (carcass) |

No |

Yes* |

No |

No |

| Post-intervention (carcass) |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Intervention (equipment surface) |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Post-chill (carcass) |

No |

Yes* |

No |

No |

| At temperature check (carcass) |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| At dispatch (carcass) |

No |

No |

No |

No |

*Stages where 2 isolates were collected; **Stages where 3 isolates were collected; ***Stages where 4 isolates were collected.

Table 7.Stages where E. coli isolates were selected for WGS analysis.

| Processing stage (type of sample) - time |

Site A Mar |

Site B Mar |

Site A Jun |

Site B Jun |

Site A Oct |

Site B Nov |

| Crate (litter) |

No |

Yes |

Yes* |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes* |

| Dirty crate (surface) |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

| Cleaned crate (surface) |

Yes |

Yes* |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

| Post-stun (feathers) |

Yes |

Yes* |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

| Post-stun (feet) |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

| Scalding (water) |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post-defeathering (feathers) |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

Yes* |

No |

| Feet removal (feet) |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

| Pre-evisceration rehang (carcass) |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

| Post-evisceration (viscera) |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes* |

Yes* |

| Post-mortem inspection (carcass) |

No |

Yes |

Yes* |

No |

No |

No |

| Post-mortem inspection (viscera) |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

| Neck skin trim (neck skin) |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes** |

Yes* |

| Post-inside-outside wash (carcass) |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes* |

No |

| Post-intervention (carcass) |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

| Intervention (equipment surface) |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Post-chill (carcass) |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes* |

| At temperature check (carcass) |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| At dispatch (carcass) |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

*Stages where 2 isolates were collected; **Stages where 3 isolates were collected.

2.4.2. Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS)

DNA extraction was conducted using the Promega Wizard Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (Madison, WI, USA), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Libraries for Illumina reads was prepared with the Illumina Nextera XT kit and libraries were assessed for quality with Qubit (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) prior to WGS.

All the WGS was carried out by CosmosID, an external laboratory. Samples were sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq 550 platform (San Diego, CA, USA), producing paired-end reads at a maximum length of 150 bases. Raw sequence data trimming was performed for adapters and low-quality bases using bbduk and applying standard parameters (phred quality trimq = 22, and minimum length minlen = 36).

De novo assembly was performed in PATRIC v. p3-build-178 via Unicycler version 0.4.8 with minimum contig length cutoff set of 300bp. Quality assessment of assemblies was performed with QUAST version 5.0.2, SamTools version 13, and Pilon version 1.23. Closest reference genomes were identified by Mash/MinHash employing the PATRIC database. Upon submission to GenBank (Bioproject PRJNA674638), assemblies were reannotated using the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (PGAP) v. 6.2. The Genomic library was prepared using Illumina TruSeq Nano DNA library preparation kit supplied by Illumina Inc. Pair-end sequencing (2 x 150 base pairs) was performed using Illumina NovaSeq 6000. The quality of sequence reads was determined using FastQC Version 0.12.0. Adapter trimming, quality filtering, and per-read quality pruning was performed using fastp software. The sequence reads were merged using PEAR v0.9.6. The filtered paired-end reads were de novo assembled using SPAdes v3.15.3. Genome quality and completeness was evaluated using CheckM v1.0.18. while quality assessment of the assembled sequence was done using QUality ASsessment Tool (QUAST) v5.2.0. Staramr v0.10 was used to examine plasmids, virulence determinants, and ARGs.

The quality of sequence reads was determined using FastQC Version 0.12.0. Adapter trimming, quality filtering, and per-read quality pruning was performed using fastp software. The sequence reads were merged using PEAR v0.9.6. The filtered paired-end reads were de novo assembled using SPAdes v3.15.3. Genome quality and completeness was evaluated using CheckM v1.0.18. while quality assessment of the assembled sequence was done using QUality ASsessment Tool (QUAST) v5.2.0. The identity of the presumptive isolates was confirmed using the MASH algorithm, with average nucleotide identity of our genomes to reference strains ranging from 97% to 99.1%, identifying them as either C. jejuni or E. coli. Staramr v0.10 was used to examine plasmids, virulence determinants, ARGs, and the MLST profile. For E. coli, the Achtman MLST scheme was used.

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing of samples collected across the processing chain on each visit to the two poultry processing sites was carried out to determine the diversity and abundance of bacteria, ARGs, and phages present in samples. In all 201 samples collected from both poultry sites in this project were sent for shotgun metagenomic sequencing.

Samples were processed as follows: The QIAGEN DNeasy PowerFood Pro Kit was used to extract genomic DNA from samples according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted DNA was tested for quality and quantity using a Qubit 4 fluorometer and Thermofisher Scientific’s QubitTM dsDNA HS Assay Kit. DNA was then transported to CosmosID (a commercial external laboratory) for library preparation and sequencing. Briefly, the Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina) was used to produce genomic DNA libraries, which were then indexed using the IDT Unique Dual adapters with a total DNA input of 1ng. The genomic DNA was fragmented with a proportionate quantity of Illumina Nextera XT fragmentation enzyme prior to amplification. Following that, adapters were added to each sample, followed by 12 cycles of PCR amplification to create libraries. The DNA libraries were purified with Beckman Coulter Ampure magnetic beads and eluted in QIAGEN EB buffer. The Qubit 4 fluorometer and QubitTM dsDNA HS Assay Kit were used to confirm the quality and quantity of DNA libraries. Afterwards, the libraries were sequenced at 2x150bp on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform.

Bioinformatic analysis was carried out on the CosmosID interface (CosmosID Metagenomics Cloud, CosmosID Inc.,). To quote the CosmosID method document, “The system utilizes a high-performance data-mining k-mer algorithm that rapidly disambiguates millions of short sequences reads into the discrete genomes engendering the particular sequences. The pipeline has two separable comparators: the first consists of a pre-computation phase for reference databases and the second is a per-sample computation. The input to the pre-computation phase are databases of reference genomes, virulence markers and antimicrobial resistance markers that are continuously curated by CosmosID scientists. The output of the pre-computational phase is a phylogeny tree of microbes, together with sets of variable length k-mer fingerprints (biomarkers) uniquely associated with distinct branches and leaves of the tree. The second per-sample computational phase searches the hundreds of millions of short sequence reads, or alternatively contigs from draft de novo assemblies, against the fingerprint sets. This query enables the sensitive yet highly precise detection and taxonomic classification of microbial NGS reads. The resulting statistics are analysed to return the fine-grain taxonomic and relative abundance estimates for the microbial NGS datasets. To exclude false positive identifications the results are filtered using a filtering threshold derived based on internal statistical scores that are determined by analysing a large number of diverse metagenomes. The same approach is applied to enable the sensitive and accurate detection of genetic markers for virulence and for resistance to antibiotics.”

3. Results

All results are presented in this section except for the systematic review. A detailed summary of the literature can be found in the Appendix of this report.

3.1. Field and laboratory sampling and analysis

This section presents the findings from our comprehensive field and laboratory investigations involving sample collection from 2 poultry processing environments and laboratory analysis using traditional and molecular biology techniques.

Site A and Site B were two chicken processing facilities with some notable similarities and differences. Both sites operate two processing lines and source their chickens from Red Tractor Assurance (RTA) farms in the UK. However, Site A has a higher processing capacity, handling up to 400,000 birds per day from Monday to Thursday and 200,000 birds on Friday and Saturday, with faster line speeds of about 217 birds per minute. In contrast, Site B processes 320,000 to 370,000 birds daily across two shifts, with slower line speeds of 175 birds per minute. A total of 17 farms supplied all the chickens processed in Site A during the collection period and a total of 16 farms supplied Site B during the collection period. The number of farms supplying each site varied slightly across different visits, ranging from 5 to 7 for both sites. Site A’s supplying farms were generally closer, with average distances ranging from 18 to 23 miles, while Site B’s farms were farther away, with average distances between 50 and 82 miles. Both sites showed some variation in their supplying farms across different visits, in addition in Site B there were variations in the farms that supply each processing line on each collection day. For Site A October collection all farms that supplied chicken varied completely from farms that supplied March and June samples.

For the laboratory sampling and analysis, we report on:

-

the prevalence and distribution of Campylobacter spp. and E. coli throughout various stages of poultry processing;

-

antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of isolates, including MIC data;

-

the resistance patterns observed in isolates across different processing stages;

-

WGS analysis of individual bacterial isolates, focusing on the identification of ARGs and plasmids,

and finally,

-

shotgun metagenomic analysis to assess genetic diversity among isolates and detect ARGs within the broader microbial community.

3.1.1. Occurrence of Campylobacter spp. and E. coli along the processing chain

In this study a total 376 samples were collected along the processing line in 2 poultry plants on 3 visits to each. In Table 8 and 9, “No”: Indicates that the specific bacterium was not isolated from the sample; “Yes”: Indicates that the specific bacterium was successfully isolated from the sample and “Ns” (Not Sampled): Indicates that no sample was collected or analysed for the specific bacterium at this point or stage.

Of these 376 samples, 65.1% were positive for Campylobacter spp. (Table 8). Generally, Campylobacter spp. were detected at fewer processing stages in both plants as the carcasses progressed along the processing chain, although Campylobacter spp. were still detected in samples at late processing stages.

Table 8.The number of samples collected at different processing points in both plants that were positive for the presence of Campylobacter spp.

| Processing stage |

am (1) |

am (2) |

am (3) |

pm (1) |

pm (2) |

pm (3) |

| Crate (litter) - Site A - June |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Crate (litter) - Site B - June |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Crate (litter) - Site A - October |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Crate (litter) - Site B - November |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Crate (dirty) - Site A - June |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Crate (dirty) - Site B - June |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Crate (dirty) - Site A - October |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

| Crate (dirty) - Site B - November |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Crate (clean) - Site A - June |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Crate (clean) - Site B - June |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Crate (clean) - Site A - October |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Crate (clean) - Site B - November |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Post-Stun (feathers) - Site A - June |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post-Stun (feathers) - Site B - June |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

| Post-Stun (feathers) - Site A - October |

No |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post-Stun (feathers) - Site B - November |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Ns |

Ns |

Ns |

| Pre-Evisceration rehang (carcass) - Site A - June |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post-Stun (feet)- Site A - June |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post-Stun (feet) - Site A - October |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Post-Stun (feet) - Site B - November |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

| Scalding (water)- Site A - June |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Scalding (water) - Site B - June |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Scalding (water) - Site A - October |

No |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

| Scalding (water) - Site B - November |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post-Defeathering_Foot removal (feathers)- Site A - June |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post-Defeathering_Foot removal (feathers) - Site A - Oct |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

| Post-Defeathering_Foot removal (feet)- Site A - June |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post-Defeathering_Foot removal (feet) - Site B - June |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post-Defeathering_Foot removal (feet) - Site A - October |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Post-Defeathering_Foot removal (feet) - Site B - Nov |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Neck skin trim (neck skin)- Site A - June |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Pre-Evisceration rehang (carcass) - Site B - June |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Pre-Evisceration rehang (carcass) - Site A - October |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Pre-Evisceration rehang (carcass) - Site B - Nov |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Post Mortem (PM) Inspection (carcass) - Site A - June |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post-Evisceration (viscera) - Site B - June |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post-Evisceration (viscera) - Site A - October |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

| Post-Evisceration (viscera) - Site B - November |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post Mortem (PM) Inspection (viscera)- Site A - June |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post Mortem (PM) Inspection (carcass) - Site B - June |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post Mortem (PM) Inspection (carcass) - Site A - Oct |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Post Mortem (PM) Inspection (carcass) - Site B - Nov |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Post Inside Outside (IO) wash (carcass) - Site A - June |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post Mortem (PM) Inspection (viscera) - Site B - June |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post Mortem (PM) Inspection (viscera) - Site A - October |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

| Post Mortem (PM) Inspection (viscera) - Site B - November |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Neck skin trim (neck skin) - Site B - June |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

| Neck skin trim (neck skin) - Site A - October |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Neck skin trim (neck skin) - Site B - November |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post-intervention (equipment) - Site B - June |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

| Inside Outside (IO) wash (carcass) - Site B - June |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Inside Outside (IO) wash (carcass) - Site A - Oct |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Inside Outside (IO) wash (carcass) - Site B - Nov |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

| Post-Intervention (carcass) - Site B - June |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post-Intervention (carcass) - Site B - November |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Post-intervention (equipment) - Site B - November |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Post-Evisceration (viscera)- Site A - June |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post-Chill (carcass) - Site A - June |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

| Post-Chill (carcass) - Site B - June |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

| Post-Chill (carcass) - Site A - October |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Post-Chill (carcass) - Site B - November |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| At temperature check (carcass) - Site B - June |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

| At temperature check (carcass) - Site B - Nov |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

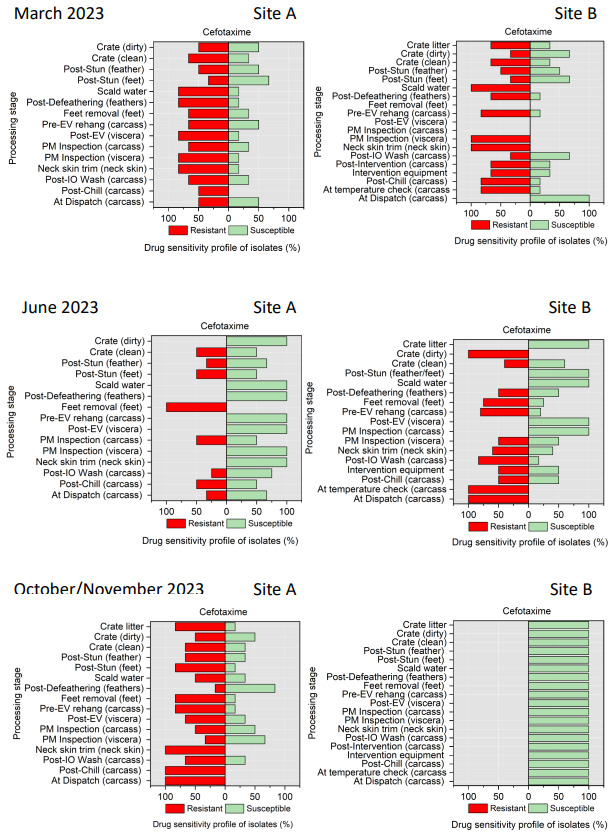

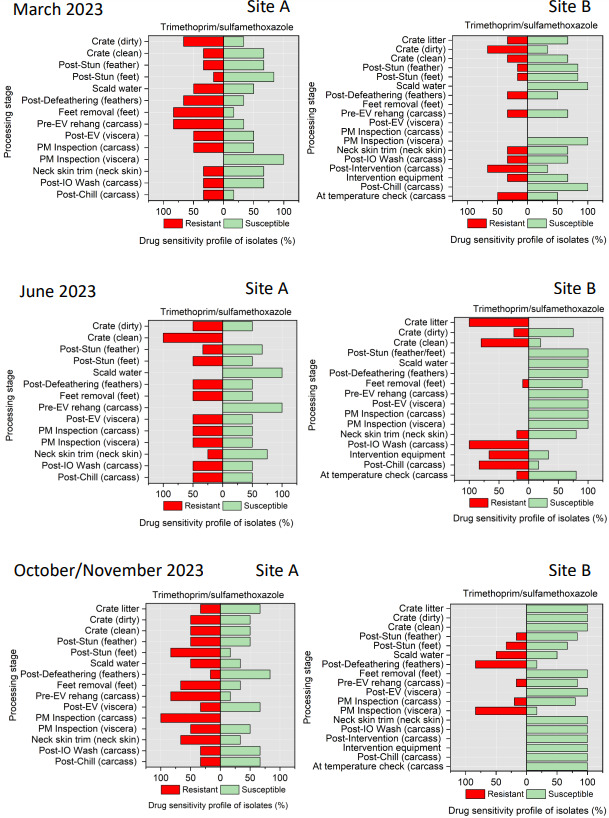

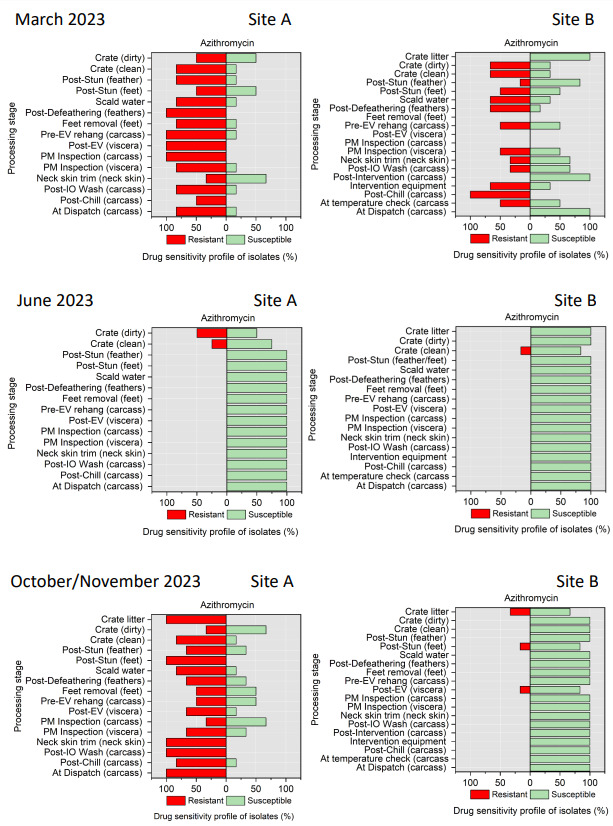

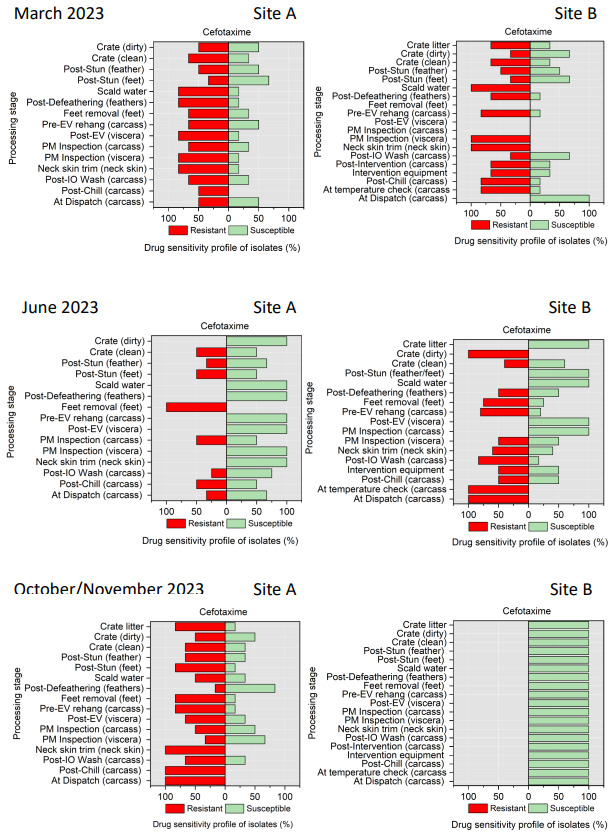

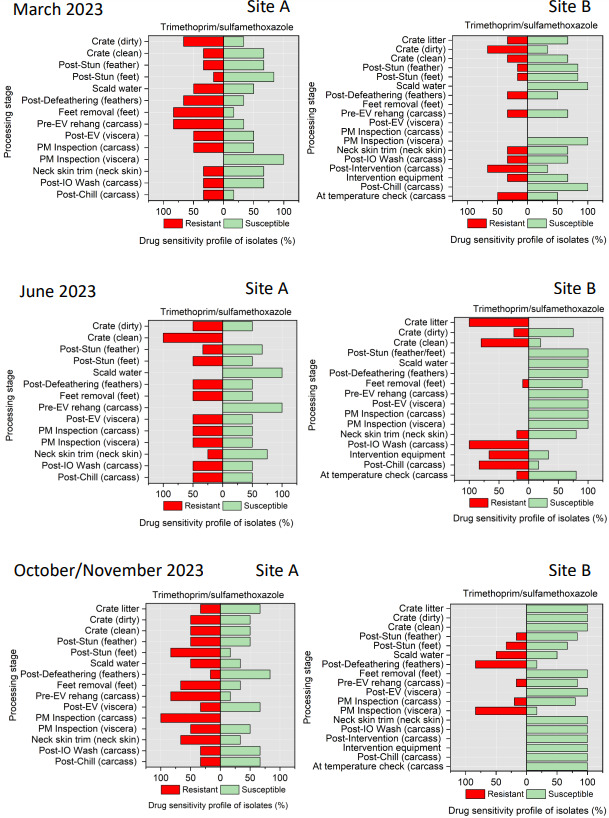

No |