Executive summary

Background and methodology

-

Increasing the number of fruits and vegetables grown in urban areas (urban-grown food) has been suggested as a potential contributor to food system transformation. Producing and consuming more food grown in urban areas may have health and sustainability benefits by reducing reliance on imports and increasing people’s access to fresh-fruits and vegetables.

-

Consumer and stakeholder acceptance of urban-grown food is important to achieving these proposed benefits. However, previous international research suggests that consumers may be unfamiliar with urban-grown food, or have concerns about the safety, quality and naturalness of such foods. Similar research suggests that food system stakeholders may have queries around the scalability, regulation, sustainability, and feasibility of urban-grown food.

-

To date, understanding of UK consumer and stakeholder preferences regarding urban-grown food, or if consumers would be willing to accept it, is limited. No large-scale studies of UK consumer perceptions of urban-grown food and reasons for acceptance/non-acceptance have been identified. A two-stranded research project was carried out to address this.

1. A consumer survey was conducted between 11th May and 2nd August 2022 to explore consumer perceptions of urban-grown food (fruit and vegetables grown in urban areas). A sample of 998 UK residents aged 18-79 took part in the survey which asked respondents to make choices about food with no labels and foods labelled as urban-grown or farm-grown or without labels. They were also asked to indicate the amounts of money they would be willing to pay for the foods and provided details about their perceptions of urban-grown food.

2. An online stakeholder workshop and stakeholder interviews were carried out in March 2023 to explore stakeholder views and identify potential next steps to increase acceptance. This was attended by 6 food system stakeholders, followed by brief interviews with a further 9 representatives from food industry bodies. The workshop and interviews explored stakeholders’ perceived barriers to increasing use of urban-grown food, and perceived next steps to achieving this in the UK food system.

Main findings

-

Survey respondents were less likely to choose foods labelled as urban-grown (48% less likely to compared to foods with no label, and 57% less likely compared to foods labelled as farm-grown).

-

The amounts of money that survey respondents were willing to pay for foods did not differ across foods labelled as urban-grown, farm-grown, or foods with no label.

-

Whilst generally not familiar with urban-grown food, survey respondents reported moderate-high levels of agreement with statements about the health, safety, quality, freshness and nutrition of, food grown in this way.

-

Findings suggest that in order to increase consumer acceptance of urban-grown food, consumers need: 1. more information about urban-grown food, 2. assurance about the health and safety of such food, and 3. appropriate pricing.

-

Common barriers to acceptance of urban-grown food amongst stakeholders related to scalability, supply certainty, and marketing or labelling of urban-grown food.

-

Findings suggest that in order to increase acceptance of urban grown food amongst stakeholders, they require: 1. clear definitions and marketing of urban-grown food, 2. clarification of the impact of urban pollution on urban-grown food, 3. assurance and evidence of the scalability of urban food growing, and, reliability of supplies, and 4. appropriate guidance, regulation and certification for urban-grown food to ensure it meets safety and quality standards.

Chapter 1 – Consumer Online Survey

Background and objectives

The Food Standards Agency (FSA) is a partner in the Transforming the UK Food Systems Strategic Priorities Fund (TUKFS SPF), which is addressing critical questions around how to transform the UK food system and place healthy people and a healthy planet at its centre.

Increasing the UK’s production and use of fruit and vegetables grown in urban areas (urban-grown food) has been highlighted as a potential contributor to food system transformation. Growing more food in urban areas may benefit health and sustainability by reducing food miles and improving people’s access to fresh fruits and vegetables (Evans et al., 2022; Kourmpetli et al., 2022). However, consumer acceptance of urban-grown food is crucial to achieving such benefits. Understanding consumer preferences and overcoming perceived barriers to acceptance of urban-grown food will be important for efforts that attempt to maximise the potential benefits of urban-grown food.

A recent review of studies that assessed consumer perceptions of urban-grown food concluded that consumer views are mixed. Whilst some studies reported that consumers may be open to trying or buying urban-grown food, others indicate that concerns around safety, perceived naturalness, and quality of such foods may be a barrier to acceptance for consumers (B. Mead et al., 2024). Much of the research reviewed considered urban-grown food produced by either specific cultivation methods (e.g. soil-based urban farming, hydroponic growing) or reported consumer opinions of urban-grown food without comparisons to non-urban grown foods. Furthermore, only one study reviewed reported findings from UK-based consumers. UK consumer views on urban-grown food are largely unexplored and there is a lack of understanding of how UK consumers make decisions about urban-grown food, and if their concerns or barriers around the consumption of such foods are similar to those identified in international research. To fill this evidence gap, a survey of UK consumers was carried out using an online experimental paradigm to explore current preference, awareness, perceptions and enablers or barriers to acceptance of urban-grown food.

Methodology

A sample of 998 UK residents aged 18-79 took part in an online survey between 11th May and 2nd August 2022. Respondents were recruited via Prolific Academic online participant panel (88%) and via adverts placed on social media in community and food growing-relevant groups (12%).

Recruitment via Prolific was stratified to be representative of the UK population for age, gender and ethnicity. Recruitment via online advertising was targeted at members of the general public and those likely to be already aware of urban-grown food to capture respondents with a range of familiarity with urban-grown food. This recruitment approach has been used in previous research (B. R. Mead et al., 2021).

Considering the lack of formal definitions of urban-grown food in the literature the following definitions were devised by the researchers and provided to respondents in the first part of the survey.

Urban agriculture/ urban-grown food means growing fruit and vegetables in urban, suburban and surrounding areas. This could be in urban farms or community gardens, using soil-less growing systems, or on rooftops in urban areas.

Traditional agriculture/farm grown food means growing fruit and vegetables using standard farming methods. These activities occur in the countryside, on a large area of farmland.

All respondents then completed three blocks of the survey: 1. A food choice and willingness to pay task, 2. rating scales to report their perceptions of urban-grown food, and 3. free-text written responses to questions about their reasons for acceptance/non-acceptance of urban-grown food.

Food choice and willingness to pay task

Upon entering the survey respondents were randomly allocated to one of four experimental conditions for a food choice and willingness to pay task. The tasks were adapted from a previous study of consumer acceptance of sustainability labelling and impact on food choice (Duckworth et al., 2022). The tasks used a stated preference approach based on a discrete choice experiment to assess choice and willingness to pay as proxies for behaviour.

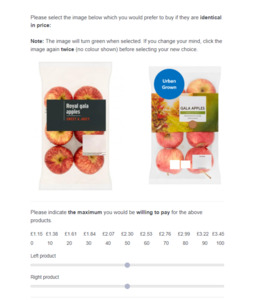

In each condition respondents were presented with the same ten image pairs. Each pair consisted of visually similar images of fruits and vegetables[1], in supermarket packaging with brand information obscured. The only variance between the conditions was whether information regarding location of growth was added to the image. Images either did not carry this information or were labelled as urban-grown or farm-grown [2].

Respondents were asked to choose which food of each pair they would prefer to buy (assuming identical pricing). In the control condition neither image in the pair had a growth location label. In the other conditions, respondents were asked to choose between fruit or vegetables labelled as: 1. farm grown or urban grown; 2. farm grown or food with no growth location label, 3. Urban grown or food with no growth location label. See figure 1 for an example of foods presented with growth location labels or no label.

Immediately after making their response for the food choice task, respondents were asked to use a 0-100 monetary scale[3] to indicate how much they would be willing to pay for each food item in the pair just presented to them (see Figure 2 for an example of this).

Perceptions of urban-grown food

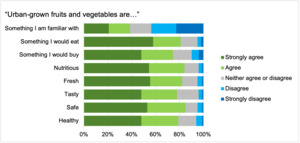

Next, respondents were asked to indicate their level with agreement (on a scale from 0 = strongly disagree to 100 = strongly agree) with the following statements:

-

Urban grown fruits and vegetables are healthy.

-

Urban grown fruits and vegetables are safe to eat.

-

Urban grown fruits and vegetables are tasty.

-

Urban grown fruits and vegetables are fresh.

-

Urban grown fruits and vegetables are nutritious.

-

Urban grown fruits and vegetables are something I would buy.

-

Urban grown fruits and vegetables are something I would eat.

-

Urban grown fruits and vegetables are something I am familiar with.

Responses on the agreement scale were subsequently transformed in to categories reflecting levels of agreement in the following way: ≤ 20 = Strongly disagree; 21 - 40 = Disagree; 41 - 60 = Neither agree or disagree; 61 – 80 = Agree; ≥ 81 = Strongly agree.

Reasons for acceptance/non-acceptance of urban grown food

Reasons for acceptance/non-acceptance of urban grown food were explored through free-text response questions. Respondents were asked to elaborate on the reasons for their choices in the survey (food choices, willingness to pay, and perceptions of urban-grown food) via the questions "Please explain the reasons for your choices above". They were also asked what would make them more likely and less likely to accept urban-grown food. The content of text responses was analysed to identify common themes and patterns in the response. The narrative overview of findings is supported by example, verbatim quotes.

Reporting notes

-

Five respondents (0.5%) chose not to disclose their gender, and six (0.6%) indicated that their gender was not listed in the questionnaire. Due to the small number of respondents in these categories, findings that refer to gender included only data from participants who reported their gender as male or female.

-

Total percentages may not add up due to rounding.

-

All reported differences are significant to the p <.05 level, unless otherwise stated.

Online survey - Main findings

Choice of foods labelled as “urban-grown”

Respondents were unlikely to choose foods labelled as “urban-grown” when they are offered alongside foods with no production information present, or directly compared to foods labelled as “farm-grown”, suggesting low levels of preference for urban-grown food in UK consumers. Respondents were 48% less likely to choose foods labelled as “urban grown” compared to foods with no label, and 57% less likely to choose food labelled “urban grown” over foods labelled “farm-grown”.

There was no significant difference in how often respondents chose foods labelled as farm-grown compared to foods with no labels. Age and gender of respondents did not significantly affect how often foods with each label were chose.

Willingness to pay for food labelled as “urban-grown”

The amounts of money that respondents were willing to pay for foods was similar regardless of which type of labels were displayed to respondents. Age did not significantly affect how much respondents were willing to pay for foods. Irrespective of label type, female respondents consistently reported being willing to pay 4.2% (£0.02 - £0.09) less for foods than male respondents, and this was consistent across all label types.

These findings suggest that UK consumers are willing to pay similar amounts of money for foods grown via traditional agriculture, urban food growing, or foods with no production details displayed on them. This is consistent with previous research in this area that shows little difference in the amount of money people report being willing to pay for urban-grown food, compared to traditionally farmed foods (Sanyé-Mengual et al., 2018), suggesting that consumers may be unlikely to accept urban-grown food if it is priced as more expensive than other foods.

Across all foods and types of labels, the amount of money that respondents reported being willing to pay for all foods in the survey was 5.9-6.2% (£0.04 - £0.14) less than the foods’ retail value in supermarkets as of May 2022. It should also be noted that analyses of willingness to pay did not consider participant income, which may influence results.

Perceptions of urban-grown food

Most respondents indicated some level of agreement with statements that urban grown fruits and vegetables are healthy, safe, tasty, fresh, nutritious, something they would buy, and something they would eat (76 - 85% providing ratings classed as “Agree” or “Strongly agree”; Figure 3). This reflects, overall, generally positive perceptions of urban-grown food amongst respondents despite the lower likelihood of choosing such products in the food choice task. Previous studies have shown that consumers may have a positive opinion of urban-grown food, but may still be reluctant to choose or consume it due to their unfamiliarity with such produce (Grebitus et al., 2017). Consumers may perceive urban-grown food positively but still require additional information or assurances about it to adopt it.

Over a third of respondents reported being familiar with urban-grown food, with 39% reporting agreement with the statement "Urban-grown food is something I am familiar with. A tenth of respondents (116; 12%) reported that they were already engaged or involved with a form of urban-food growing, and for the vast majority (115; 99%) this was through growing food at home or in an allotment.

Compared to male respondents, females tended to report greater agreement with the statements that urban-grown fruits and vegetables were healthy, safe, tasty, nutritious, and something they would buy. Male and female respondents did not differ in level or agreement to statements that urban-grown food was fresh, something they would eat, or something they are familiar[4].

Older respondents were more likely to agree with statements that urban-grown food was safe, tasty, fresh, nutritious and something respondents would buy. No associations were seen between age and levels of agreement for statements that urban-grown food was healthy, something respondents would eat, or something respondents were familiar with.

Reasons for acceptance/non-acceptance of urban-grown food

Reasons for responses to the food choice task, willingness to pay task, and perceptions of urban-grown food statements

The final part of the survey asked respondents to explain their responses to the preceding questions. Responses were based around four key themes, detailed below.

- Impact of level of familiarity with urban-grown food

It was evident that the concept of urban-grown food was novel or unfamiliar to some respondents, leading them to rely on their initial perceptions of it as presented in the survey to make their decisions:

Although I do not know much about urban grown fruit and vegetables I cannot see why they would not be as safe and healthy to eat as traditionally grown produce. – Anonymous respondent A.

Others, however, reported existing familiarity with urban-grown food, which may have influenced their responses in the survey.

- Attempts to use existing knowledge to guide responses

Perhaps due to lack of familiarity with urban-grown food, many responses appeared to suggest that survey respondents made assumptions about urban-grown food and tried to apply existing knowledge of food production or urban areas to the concept to explain their reasoning:

Wasn’t really aware of the concept so think my scores are based on initial perceptions without any understanding or knowledge of nutritional impact etc - Anonymous respondent B

- Concerns about safety, pollution and quality

Some respondents’ explanations about their reasoning for choices made in the survey indicated that they were concerned around the negative impact of the urban environment on food:

I worry about the impact of pollution on urban grown fruit and vegetables - Anonymous respondent C

I assume they would be healthy buy the pollution from the city might affect them and cause them to be of poorer quality/nutrition - Anonymous respondent D

- Preferences for non-urban-grown food

A tendency to prefer alternatives to urban-grown food was reported by some respondents, without further clarification as to the reasons:

I would prefer to buy and eat products grown in the countryside - Anonymous respondent F

In summary, it appears that when making decisions in the survey, respondents relied on either existing understanding of urban-grown food, or their interpretation and associations with related concepts. They considered the safety and quality of urban-grown food and drew comparisons with other means of food production when making their choices. Unfamiliarity with urban-grown food appears to be a contributing factor to this. Initiatives to promote urban-grown food should therefore begin with increasing awareness and understanding of such foods to enable consumers to make informed choices around this.

Responses to questions about what would make respondents more or less likely to accept urban-grown food

Analyses of responses to the two questions “what would make you more likely/what would make you less likely to accept urban-grown food” revealed some similar themes to analysis of respondents’ reasons for their choices in the survey. However, they provide more detailed understanding of consumer requirements for urban-grown food. Common themes of unfamiliarity with urban-grown food, concerns about safety, pollution and quality were evident here. In addition, details of acceptance being potentially contingent on assurances about urban-grown food, and the standards that consumers may be likely to expect, were apparent in these data. Six key themes were apparent and are discussed in turn below.

- The need for more knowledge and assurance

The need for more knowledge about urban-grown food was evident when respondents expressed what would help them to be more accepting of urban-grown food. Respondents indicated a need to know more about the way urban-grown food was produced, and assurances that it was healthy, of similar quality (freshness, taste and nutrition) and as safe as other fruits and vegetables. Acceptance for many respondents appeared to be contingent on this, with common responses highlighting that respondents may be accepting of such foods if they received such assurances. This was common in responses to the questions “In your opinion, what would make you more likely to accept urban-grown food?”

Quality: If I knew more about it and the products looked healthy and had a good colour – Anonymous respondent G.

Production method: Understanding exactly how the produce was being grown. – Anonymous respondent I.

Safety: The reassurance that it’s been grown to a certain health and safety standard. – Anonymous respondent J.

Respondents identified a range of desired sources for such assurances, indicating the potential importance of communication via preferred methods and from trusted information streams in promoting consumer acceptance of urban-grown food. “Studies”, “a paper”, “publicity” and “certification” were frequently identified as examples of this, such as the desire to see scientific studies confirming that the safety and quality of urban-grown produce was equivalent to other fruits and vegetables. The role of food safety regulators was mentioned to a lesser extent, although some respondents reasoned that if food was available to buy it would have passed existing safety checks and would therefore be safe to consume.

- Sustainability and environmental benefits

Respondents highlighted sustainability and environmental benefits as considerations for accepting urban-grown food.

Specific advantages such as lower environment footprint, superior price or quality. – Anonymous respondent K

Others focused on an assumption that urban-grown food would be free of pesticides and therefore better for them and the environment:

I think they are a good choice, maybe less pesticides etc used – Anonymous respondent L

This theme reflects consumer thoughts that urban-grown food would or should have benefits for the environment and sustainability. It is unclear how acceptance may be contingent on this, although this theme indicates that consumers have expectations of such benefits relating to urban-grown food.

- Pollution and safety concerns

Related to the theme of sustainability and environmental concern, pollution and safety was a recurring theme in the data. Assumptions that urban-grown food would be subject to pollution or contamination, and the need for reassurance that this was not the case or would not be harmful, appear to be crucial in consumer appraisals of urban-grown food. “Pollution” from urban areas was cited as a concern or barrier to acceptance by many respondents:

A lower price, a guarantee that they were grown in an area protected from pollution. - Anonymous respondent M.

If it had been tested for pollution and residues and produced without chemicals and pesticides and not transported for lots of miles. – Anonymous respondent N

This appears to be related to expectations that food grown in urban areas may absorb or be contaminated by urban pollution, such as emissions or waste. This is also a commonly-cited barrier to acceptance of urban-grown food in other studies (e.g. Sanyé-Mengual et al., 2018)

- Ambivalence

Many respondents reported neutral opinions or ambivalence towards urban-grown food as the reasons for their choices, with some saying that they don’t see any difference between urban-grown and farm-grown foods:

I don’t see it as very different from farm grown fruit and veg – Anonymous respondent O.

I don’t really care where my food is grown – Anonymous respondent P.

This theme is consistent with previous findings that some consumers do not express interest or strong opinions in the idea of urban-grown food (B. Mead et al., 2024). Therefore, respondents who are ambivalent towards urban-grown food and do not have strong objections may also be open to efforts to promote adoption of urban-grown food.

- Competitive Pricing

Price was a dominant theme in text responses. A large number of respondents highlighted that the cost of urban-grown food would be/ is a key influence on their perceptions.

The price needs to be competitive, price would still dictate the vast majority of my food shopping – Anonymous respondent Q

Price - urban grown food is likely to be more expensive. - Anonymous respondent R

Responses relating to price mostly clustered around the proposal that consumers may be accepting of urban-grown food is it was sold at prices equivalent to farm-grown food, or cheaper. In some cases, price of food appeared to be more influential on participants’ perceptions than other themes:

I don’t pay too much attention to the food I eat. As long it’s cheap I don’t care where it’s from and I don’t see problems with urban grown vegetables – Anonymous respondent S.

- Existing positive perceptions

It should be noted that some respondents expressed existing acceptance of urban-grown food:

I have heard of these and would certainly buy them. – Anonymous respondent T.

Consumers who express an existing willingness to adopt urban-grown food or readiness to try such foods are likely to be important for efforts to upscale use of urban-grown fruits and vegetables. Providing consumers such as these with opportunities to engage with and consume urban-grown food may have a positive or reassuring impact for more sceptical consumers.

Discussion

Preferences for urban-grown food in the UK appear to be low. UK consumers are less likely to choose urban-grown food than foods labelled as “farm-grown” or foods with no label in an online food choice task. There was no difference in the amount of money consumers are willing to pay for foods labelled as “urban-grown” compared to “farm-grown” or foods with no such label. This is partly consistent with previous research in this area, where some studies report consumer acceptance of urban grown food, whilst others report ambivalence or reluctance to accept urban grown food (B. Mead et al., 2024). UK-specific research is lacking, so there is little opportunity to compare responses in this study to previous studies of UK consumers. However, coupled with the lack of difference in what consumers were willing to pay for urban-grown food versus other foods, this suggests that consumer acceptance of urban-grown food is limited in UK consumers, and if available, urban-grown food should be priced equivalently to existing fruit and vegetable options to facilitate uptake.

Consumers reported generally positive perceptions of urban-grown food when rating their agreement with the provided statements. Older participants reported more positive opinions of urban-grown food than younger participants did. This finding is at odds with previous international surveys of consumers which showed either no relationship between perception of urban-grown food and age (e.g. Sanyé-Mengual et al., 2018), or that younger consumers had more positive perceptions of urban-grown food than older consumers (Greenfeld et al., 2020; Kosoric et al., 2019). However, it should be noted that these previous studies were carried out with non-UK consumers and focused on high-tech, soil-less methods of producing food, whereas the current study did not specify particular production methods. A forthcoming review of consumer perceptions of urban-grown food indicates that production methods used in urban food growing (high-tech or low-tech) appears to influence acceptance of urban-grown food for some consumers. High-tech growing methods, such as vertical farming or soil-less production systems, may be perceived as unnatural by some consumers, whereas low-tech, soil-based production methods in urban areas may be associated with concerns about pollution for others (B. Mead et al., 2024).

Analyses of text responses to questions about consumers’ reasons for their choices and ratings of urban-grown food revealed four key themes about familiarity with such foods, attempts to use existing knowledge to understand such foods, concerns about pollution and the safety of such foods, and preference for non-urban grown food. These themes align with findings of previous work that has explored perceptions of urban-grown food in international samples (B. Mead et al., 2024) and indicates that familiarity with urban-grown food is related to greater acceptance of such food (B. Mead et al., 2024). In the current study respondents attempted to interpret urban-grown food based on their own understanding of the terms presented, or concepts they associated with these. When faced with ambiguity or acknowledging their lack of understanding of urban-grown food, respondents seemed to make comparisons with more familiar means of producing food. This may reflect an uncertainty around the novelty of urban-grown food, highlighting the need for increasing consumer awareness and understanding of this to facilitate informed decision making.

Concerns around contamination or reduced quality of food due to the urban environment was also a common theme. This is consistent with previous work that has looked at consumer perceptions of urban-grown food in North America (Grebitus et al., 2020). Consumers appear to equate urban environments with pollution, and therefore query if this would affect fruits and vegetables grown in such locations. Data on the uptake of pollutants in urban-grown food in the UK is lacking, so future initiatives to promote urban-food production may need to consider testing and mitigation strategies for this.

When consumers were asked what would make them more or less accepting of urban-grown food, responses tended to cluster around the following six themes: the need for more knowledge and assurance, sustainability or environmental benefits, pollution and safety concerns, ambivalence, competitive pricing, and existing positive perceptions of urban-grown food.

The theme “The need for more knowledge and assurance” highlights that acceptance may be contingent on assurances around the quality, safety, and knowledge of production methods of such foods. Likewise, the themes of “Sustainability and environmental benefits” and “Pollution and safety concerns” highlights that consumers have concerns around the impact of these on urban-grown produce. Concerns about pollution appear to be linked to expectations about the quality and healthiness of urban-grown food.

Returning to the theme of need for assurances, the prevalence of the themes of “Pollution and safety concerns” and “Sustainability and environmental benefits” highlight the vital role that public information campaigns and regulation may play in fostering acceptance of urban-grown food. Testing and regulation of pollution levels present in urban-grown food (if any) and effective mitigation of this by trusted regulatory bodies is likely to inspire consumer confidence in urban-grown food, thus increasing the likelihood of its proposed health and sustainability benefits being achieved.

Price of urban-grown food was also a key consideration for consumers in the current study. Whilst a study of consumers in the USA highlighted that price was a commonly-cited barrier to purchasing a type of urban-grown food produced using a soilless growing system (Short et al., 2017), a recent review indicated that food price was a potential, but not the dominant, barrier to acceptance of urban-grown food (B. Mead et al., 2024). The findings of this survey are somewhat inconsistent with this, as price was a more highly cited topic by survey respondents. This may reflect the timing of data collection for this survey. During Summer 2022 the UK was experiencing a “cost of living crisis”, with increases in inflation and everyday costs widely reported (Office for National Statistics, 2022). Therefore, money and price of food may have been more salient to respondents in the current survey than previous research. This suggests that efforts to promote the uptake and use of urban-grown food likely need to consider reflecting this in pricing structures and costs to consumers if where such produce is commercially available.

It is important to note that some survey respondent expressed existing positive perceptions of urban-grown food, which may be reflected in the positive opinion ratings for statements related to urban-grown food. This may be indicative of the proportion of the sample who were already engaged in some form of urban food growing (12%). Recruitment was targeted to include such participants to capture the opinions of a range of consumers. Consumers with such opinions are likely to be important to efforts to increase acceptance of urban-grown food as they may be more likely to purchase and consume such food. Efforts to increase adoption of urban-grown food may find success with such consumers.

In summary, this survey shows that UK consumer acceptance of urban-grown food in online choice tasks is low, but that consumers may still have positive opinions of such food. This study has identified key barriers to acceptance and needs of consumers that should be met to encourage acceptance. Future acceptance of urban-grown food may be contingent on attractive pricing for such foods, increased awareness and understanding of urban-grown food, plus assurances of the quality, safety and sustainability of fruits and vegetables grown in urban areas. This may be achieved through increased testing and regulation of such foods, alongside increasing awareness and opportunities for consumers to engage with urban-grown food. Evidence suggests that upscaling the production of urban-grown food may have benefits for health and sustainability (Kourmpetli et al., 2022); this survey identifies potential barriers to acceptance of such foods in UK consumers which need to be addressed in order to achieve this.

Chapter 2 – Stakeholder Workshop and Interviews

Background

Stakeholders across different areas of the food system, such as policy, retail, procurement, processing and hospitality, are likely to play key roles in increasing the use of urban-grown food and achieving its proposed health and sustainability benefits. Actors such as these are in positions that may enable them to facilitate use of urban-grown food and improve availability to the consumer. Whilst UK stakeholder perceptions of urban-grown food and their requirements for acceptance are under-explored, previous international research has highlighted that food system stakeholders’ express concerns around: contamination risks, scalability, sustainability, and economic risks related to urban food growing (Di Fiore et al., 2021; Specht & Sanyé-Mengual, 2017; Zambrano-Prado et al., 2021). If and how these issues are relevant to UK stakeholders, and the barriers that would need to be overcome to increase use of urban-grown food, is unclear. This research sought to address this by exploring stakeholder perceptions of urban-grown food in a sample of UK food system stakeholders.

Methodology

Fifteen stakeholders representing a range of industries within the food system provided their views on urban-grown food via an online, interactive workshop, brief interview, or written communication. Annexe 1 details the range of stakeholders and their methods of engagement with the research.

Online workshop

An online, interactive workshop was conducted on 7th March, 2023. During this one-hour session, 6 stakeholder representatives from academia, policy, consultancy and food retailers discussed key findings from strand one of this research relating to consumer perceptions of urban-grown food (Chapter 1). Stakeholders were selected from the FSA Stakeholder Register and researcher networks and recruited via opportunity sample. Participants took part in facilitated break-out room sessions, where a researcher led the discussion through a series of questions with the aid of an online whiteboard. Attendees also answered online polls during the workshop to gather data on what they perceived as key issues relating to increasing use of urban-grown food.

The workshop explored stakeholder views around:

-

the barriers to increasing the uptake of urban-grown food amongst stakeholders.

-

Necessary next steps to facilitate increased uptake of urban-grown food

-

The most important next step to facilitate increased uptake of urban-grown food.

Workshop participants also completed an online exercise where they were presented with key stakeholder barriers preventing increased uptake of urban-grown food identified by previous, international research (e.g. Di Fiore et al., 2021), and asked to rank them in order of priority. These were:

- Environmental impact is unclear.

- Risk of contamination from pollution.

- Too small scale/it's not scalable for significant food production.

- Urban-grown food isn't "natural".

Data from the online workshop comprised of poll responses, audio transcripts of discussions, the transcript of the meeting chat, and the records of break-out room discussions detailed by facilitators on online whiteboards. Data were qualitatively synthesised and a narrative summary was produced.

Stakeholder interviews

Additional views were collected via individual interviews with stakeholders in March 2023. Stakeholders were identified through the FSA Stakeholder register, research networks, and internet searches and contacted by email. Eight took part in a brief online/telephone interview, and one provided written communications.

A brief, written summary of key themes from the workshop and potential next steps for increasing use and acceptance of urban-grown food was produced and used to guide interview discussions. Interviewees were provided with the written summary and asked to review prior to their scheduled interview. During the discussion, they were asked the same first 2 questions as work shop participants, and additionally asked to feedback on a summary of responses to the third workshop question.

Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed, or written notes of responses were made during interviews and transcribed. Transcripts from discussions were collated and qualitatively synthesised with data from the stakeholder workshop to identify key themes relating to stakeholder perceptions of urban-grown food, barriers to acceptance, potential requirements for increasing use, and key “next steps” to facilitate this.

Stakeholder workshop and interviews - Main findings

Four recurring themes were evident within responses to all questions from the stakeholder workshop and interviews. These are discussed below.

Recurring themes

The term “urban-grown”

Consensus is needed on what is meant by “urban-grown food” because of the variety of food production methods this includes. Broadly speaking, the term can include food grown with or without soil, at small to large scales, ranging from urban community gardens to indoors/ underground in soil-less, high-tech production systems. A clear definition that reflects this is and is consistently used across stakeholders and food system actors is needed. This definition and information about the ways food can be produced in urban areas needs to be clearly communicated.

Related to this, multiple stakeholders highlighted the issue that the term “urban-grown” may have negative connotations due to its association with urban environments. They suggested that urban-grown produce may be more successfully marketed as “locally grown”, as labelling it as “urban” may invoke concerns or fears around safety, or comparisons with food produced in other ways.

Reliability and scale of supplies

Stakeholders need to have confidence in the scale and reliability of potential supplies from urban food growing operations. They expressed uncertainty that small-scale urban food producers could meet and guarantee the supply of produce at required scales.

Stakeholders from large scale retail or hospitality operations highlighted that they may not see urban farming operations as capable of producing the volume of produce they may need at the required frequency of deliveries, unless substantial investment is made in upscaling urban farming infrastructure. They perceived this potential as positive, should it be achieved, but currently had little confidence in this feasibility of this as the industry stands now.

Related to this, stakeholders in to the hospitality industry noted that their industry was still recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic and that the cost of urban-grown food was unclear. They suggested that urban-grown food may be unattractive or unobtainable to small-scale operations if the cost of produce is markedly higher than existing food sources.

Evidence and regulation for safety and sustainability

Similar to consumers (Chapter 1), stakeholders queried the extent to which urban-grown food produced in soil-based, outdoor mediums in urban areas would be vulnerable to pollution and contamination, and what this would mean for food safety, produce quality and consumer health. The role of production methods, such as open-field versus controlled environment production, was highlighted by multiple stakeholders as a likely consideration relating to the impact of pollution or contamination of food.

Stakeholders stressed the need to explore any impacts of pollution/contamination, and the need to communicate and share relevant evidence. Some suggested that mitigation techniques, such as washing advice on produce packaging, or regulation to reduce contamination, would be beneficial if a risk is evidenced. Others, however, highlighted that this would place additional burden on consumers or food processors, and potentially create a negative distinction between urban-grown food from existing food types.

The potential energy usage of high-tech urban food production systems was also highlighted by stakeholders, who queried if this would offset any potential sustainability gains associated with urban food production. One stakeholder involved in food procurement also highlighted that energy companies may play a role here, with investment in renewable energy for urban food production being a potential way of mitigating this.

The need for regulatory guidance, consistent standards, compliance and accountability was identified by multiple stakeholders. Several mentioned their uncertainty about how existing food safety regulation would or would not apply to urban-grown food. One stakeholder highlighted extensive, existing guidance relating to Good Agricultural Practice, and the need for urban food growing stakeholders and regulators to engage with this (for example, Position Statements by the Chilled Food Association, 2023).

Need for communication and education

The need for greater awareness of urban-grown food, the methods and logistics involved in this, potential benefits for health and sustainability, and safety and quality assurances, were key themes for stakeholders. The need for communication and education surrounding this was apparent. Stakeholders suggested that public awareness campaigns, industry publications, or FSA communications may be beneficial for raising awareness of urban-grown food and increasing knowledge amongst consumers and other stakeholders.

They highlighted such communications may alleviate concerns relating to unfamiliarity and understanding of what urban-grown food is. The FSA, government, urban food producers, and food retail industry were all suggested as sources who would work together to achieve this.

Barriers to acceptance of urban-grown food

Considering the themes discussed above, stakeholders involved in this research have identified the following barriers to acceptance of urban-grown food:

-

Lack of clarity around terminology and labelling.

-

Lack of confidence in scale a reliability of supplies.

-

Need for evidence relating to impact of pollution and contamination on produce if any).

-

Overall lack of familiarity and understanding of urban food growing, what it entails, and the health and sustainability benefits related to this.

Stakeholders’ “next steps” for increasing acceptance and use of urban-grown food

Stakeholders identified the following “next steps” for increasing the acceptance and use of urban-grown food.

-

Develop a clear definition of urban-grown food, which encapsulates the broad range of food growing methods and systems related to this, which is effectively communicated to stakeholders, and used consistently.

-

Provide evidence on the impact of urban pollution on produce, and/or strategies and regulation to mitigate this, to assure stakeholders of food safety and nutritional quality.

-

Explore stakeholders concerns around reliability of supplies of food from urban food production.

-

Develop and agree appropriate labelling for urban-grown food.

-

Effectively communicate safety assurances about urban-grown food to stakeholders and consumers.

Discussion

This study shows that UK food system stakeholders’ perceptions of urban-grown food are mixed. Stakeholders appear to acknowledge the potential benefits to health and sustainability of increasing the use of urban-grown food. However, they also highlighted key concerns around the feasibility of achieving these. They identified a common set of barriers to achieving this related to the terminology and labelling of urban-grown food, limited confidence in supply reliability and scale, uncertainty around safety and quality of produce relating to pollution in urban environments, and an overall unfamiliarity with the concept. These themes were consistent with findings of previous international research that has explored stakeholder perceptions of urban-grown food (Di Fiore et al., 2021; Specht & Sanyé-Mengual, 2017; Zambrano-Prado et al., 2021), highlighting commonalities in general food system stakeholder perceptions of food produced in this way.

Addressing identified barriers to acceptance of urban-grown food through regulation, evidence production, information campaigns, and supply assurances is key to achieving the potential benefits urban-grown food has been proposed to bring for the food system. For UK stakeholders, the source of such regulation, evidence production and information campaigns may be the FSA, other government bodies, or industry representatives. Mechanisms for achieving this will require a joined-up approach between policy makers, food safety regulators, urban food producers and food retailers to ensure consistent messaging addresses these concerns.

Chapter 3: Conclusion

This research provides the first UK data on consumer and stakeholder perceptions of urban-grown food and barriers to acceptance, and also identifies next steps to increasing acceptance of such food. UK consumer acceptance of urban-grown food was low in an online choice tasks, but consumer opinion ratings of urban-grown food appear to be more positive. Consumer acceptance of urban-grown food may be contingent on increasing consumer familiarity with such foods and providing assurances about their quality, safety, sustainability and price. Like consumers, stakeholders acknowledged the potential benefits of urban-grown food but suggested that acceptance may be contingent on receiving certain clarifications and assurances about such foods. Stakeholders also identified key issues that should be addressed in order to improve acceptance of urban-grown food. Similar to consumers, stakeholders acknowledged the need to safety confirmation as being key to acceptance. Confirmation and assurances regarding the safety of urban-grown food regarding any potential contamination pollution was a key issue for both consumers and stakeholders. Stakeholders also highlighted that the need for clarity around the labelling, and supply certainty of urban-grown food as communicated by trusted bodies and regulators will be key to achieving this

Efforts to increase UK consumer and stakeholder acceptance of urban-grown food should be designed to address the needs and barriers identified by this research. Doing so will provide assurances to consumers and stakeholders and allow for the proposed health and sustainability benefits of increasing the UK’s use of urban-grown food to be achieved.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Sophie Hardy for assistance with the online stakeholder workshop.

The foods presented to respondents were apples, broccoli, carrots, onions, pears, plums, potatoes, raspberries, strawberries, and tomatoes

To allowed for comparisons of choices within and across conditions, and to examine the effect of logo type, presentation of labels and individual food images were counterbalanced across left and right (an approach previously described by Duckworth et al (2022).

The mid-point of the monetary scale (50) for each food pair was set based on retail prices of the food on UK supermarket websites in May 2022. Each 10-point increase or decrease from the midpoint represented a progressive 10% increase or decrease in price. Prices were displayed in £GBP. Respondents were asked to use the scale to indicate how much they would be willing to pay for each food in the pair.

Analyses of age and gender differences in levels of agreement with statements about urban-grown food used an adjusted significance threshold of p<.01 to account for multiple testing.

_and_growth_location_labels.jpg)

_and_growth_location_labels.jpg)