Executive summary

The Consumer Insights Tracker is the FSA’s online monthly tracking survey. It monitors the behaviour and attitudes of those aged 16 and over in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland in relation to a range of food-related topics.

This report presents an overview of key findings from April 2024 to March 2025. Where appropriate, longer term trends over the full tracking period (from July 2023) are presented. Key findings are given below.

Concerns around food

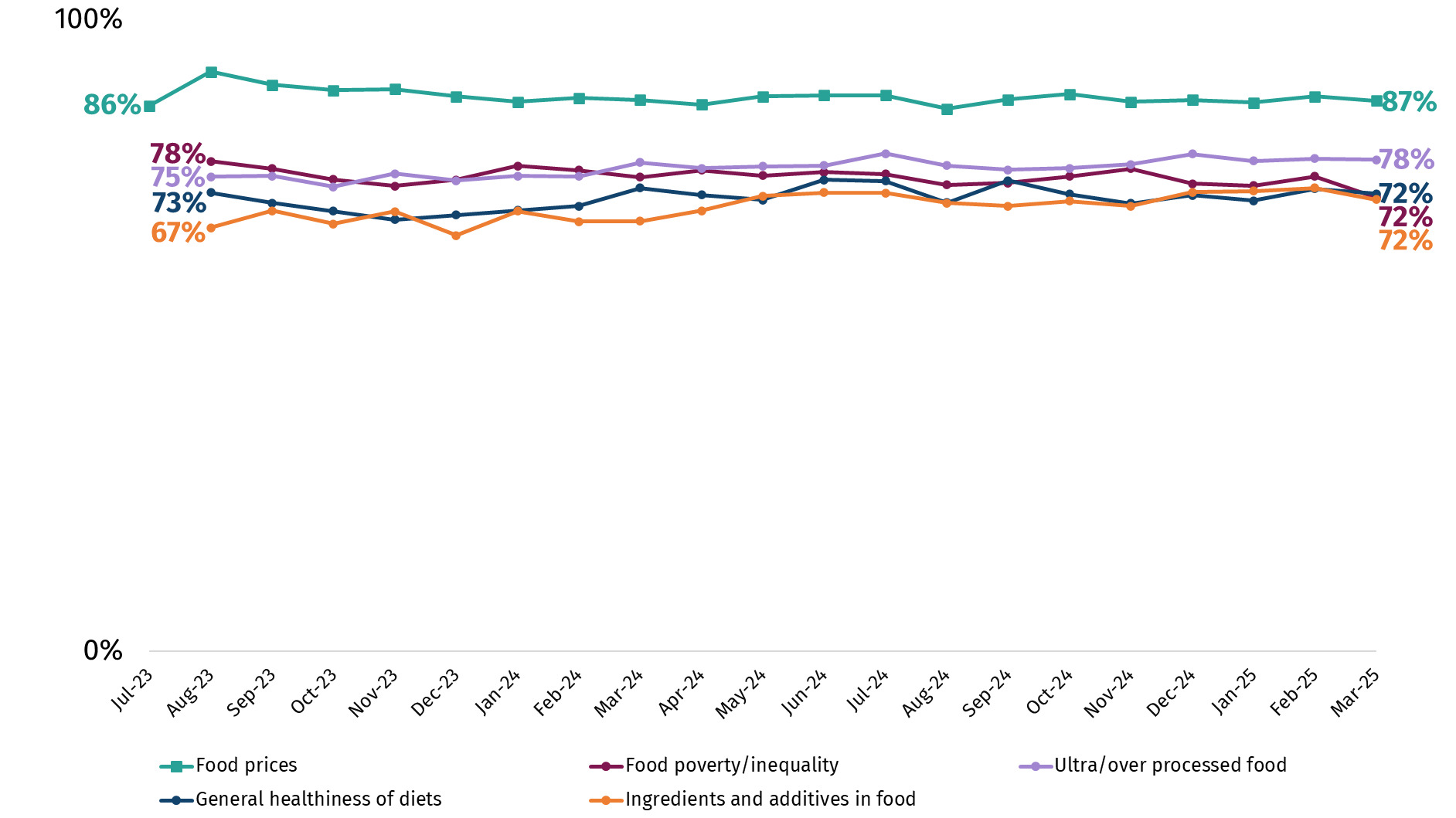

Food prices have been the top prompted concern since tracking began (in July 2023), with little variation in the proportion of respondents concerned about this issue since April 2024. Ultra-processed, or the over processing of food, has consistently been the second highest concern from April 2024 – March 2025. There has been little change in respondent’s top concerns from April 2024 to March 2025, however, ingredients and additives in food has consistently been one of the top five concerns over the past year, replacing animal welfare which was one of the top five concerns from July 2023 to March 2024.

Household food affordability

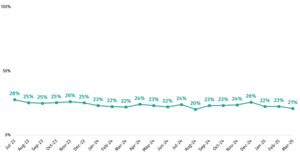

While there is high concern about food prices, the proportion of respondents worried about affording food in the next month has shown a gradual decline over time, from 28% in July 2023 to 24% in April 2024, and 21% in March 2025.

There has been a downward trend in the proportion reporting nearly all money saving shopping behaviours since April 2024. Notably, the proportion who said they choose cheaper alternatives rather than branded products has declined from 51% in April 2024 to 44% in March 2025, and the proportion who reported buying reduced or discounted foods close to their use-by-dates has declined from 42% to 34%. These kinds of money-saving behaviours were more common among those who reported being worried about food affordability.

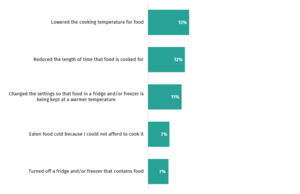

When asked about what they had done to reduce their energy bills and save money, some respondents reported engaging in potentially risky food safety behaviours. The proportion who reported doing at least one of the potentially risky behaviours asked about in the past month has shown some variation over the past year, ranging from a high of 28% in December 2024 and a low of 21% in May 2024. In March 2025, 13% said they had lowered the cooking temperature for food and 12% said they had reduced the length of time food was cooked for; 7% said they had turned off a fridge or freezer that contains food.

Food availability

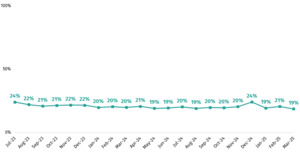

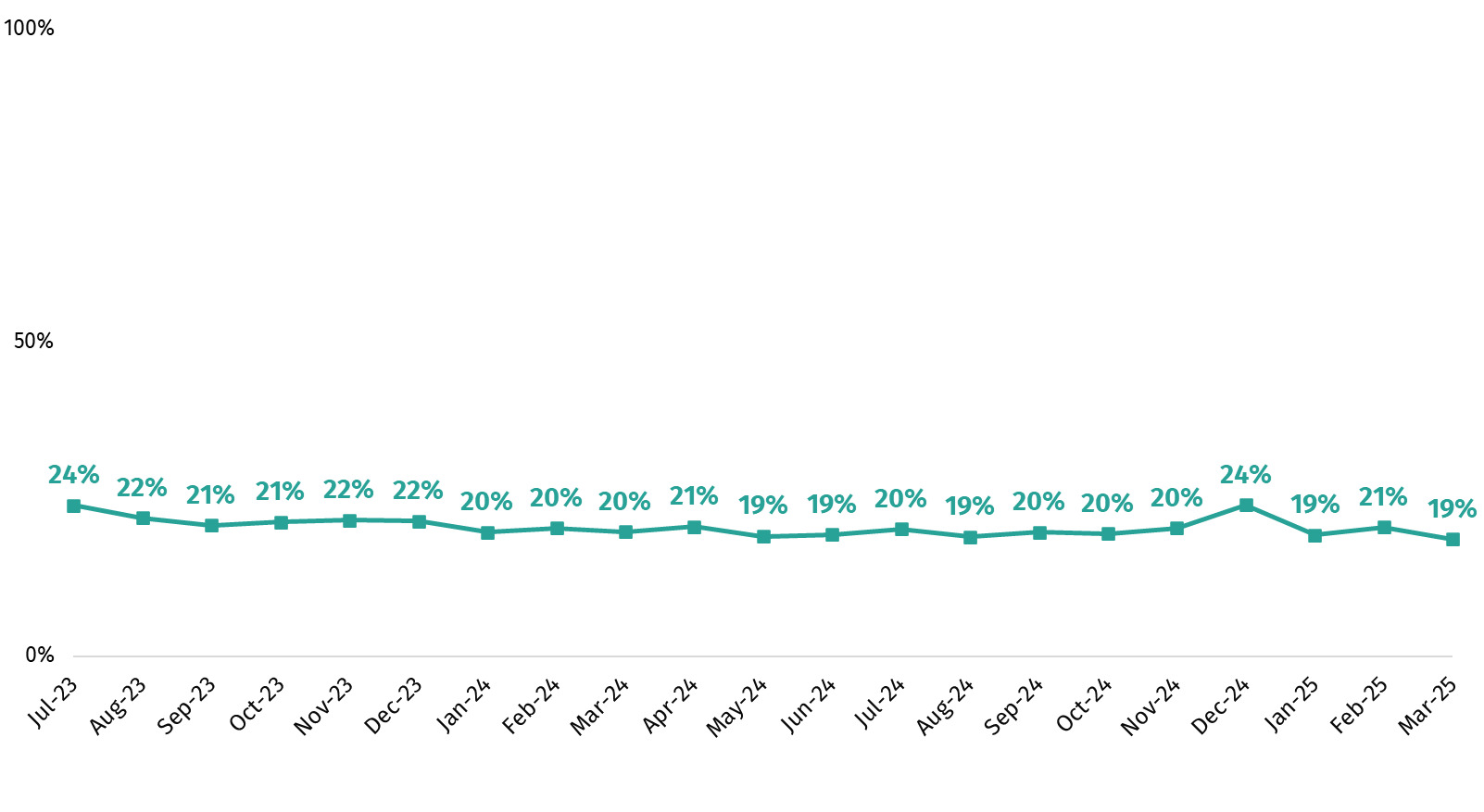

The proportion of respondents worried about food availability has remained consistent over the past year at around one in five. Nineteen percent said they were worried about this in March 2025, broadly consistent since April 2024 (21%) but a small decline from when tracking began in July 2023 (24%).

Confidence in the food supply chain

Across the past year, overall confidence in the food supply chain has stayed broadly stable with around six in ten respondents reporting they are confident. This was slightly higher in March 2025 (63%) than in April 2024 (59%) and when tracking began in July 2023 (55%).

In March 2025, just over two in five respondents (44%) said that they were confident that those involved in the food supply chain ensure that there are affordable food options for everyone. This is up from 39% in March 2024 and 34% in July 2023. However, this remains lower than the proportion of respondents who were confident the food supply chain ensures food is safe to eat (74%), there is enough food available (63%), and is of a high quality (60%).

Trust and confidence in the FSA

Among those with some knowledge of the FSA and what it does, trust in the FSA has fluctuated over the past year, peaking at 65% in July 2024. In March 2025, 64% of this group said they trust the FSA, and 5% said they distrust the FSA. Overall, there remains high confidence in the FSA’s ability to carry out its functions.

Novel foods and food production techniques

A range of questions on novel foods and food production techniques were asked between April 2024 and March 2025. These questions are only included in the survey every 6 months.

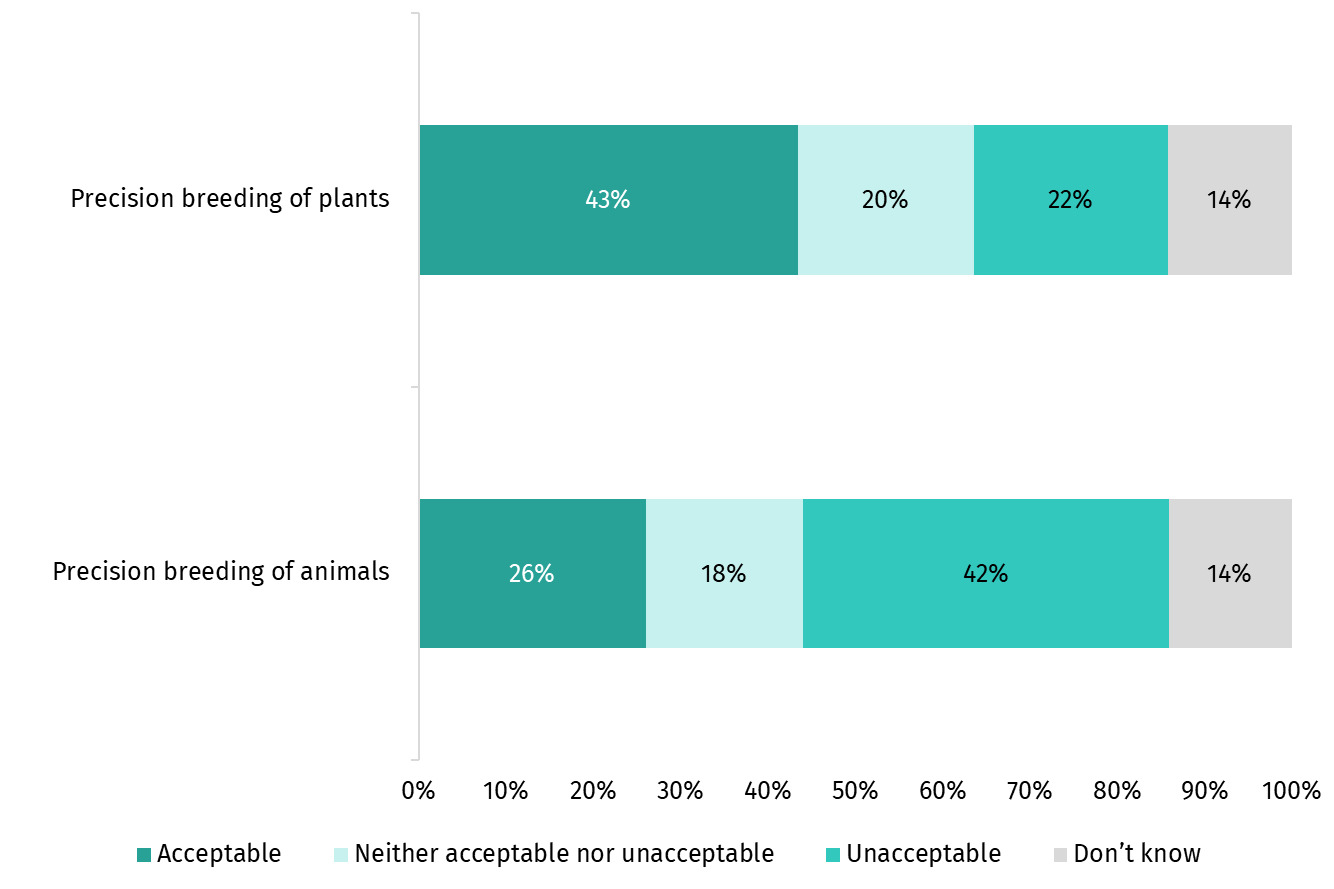

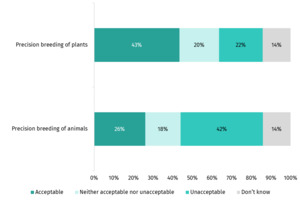

In March 2025, one in seven (13%) respondents said they had heard of precision breeding before. Precision breeding of plants (43%) was more likely to be seen as acceptable than precision breeding of animals (26%).

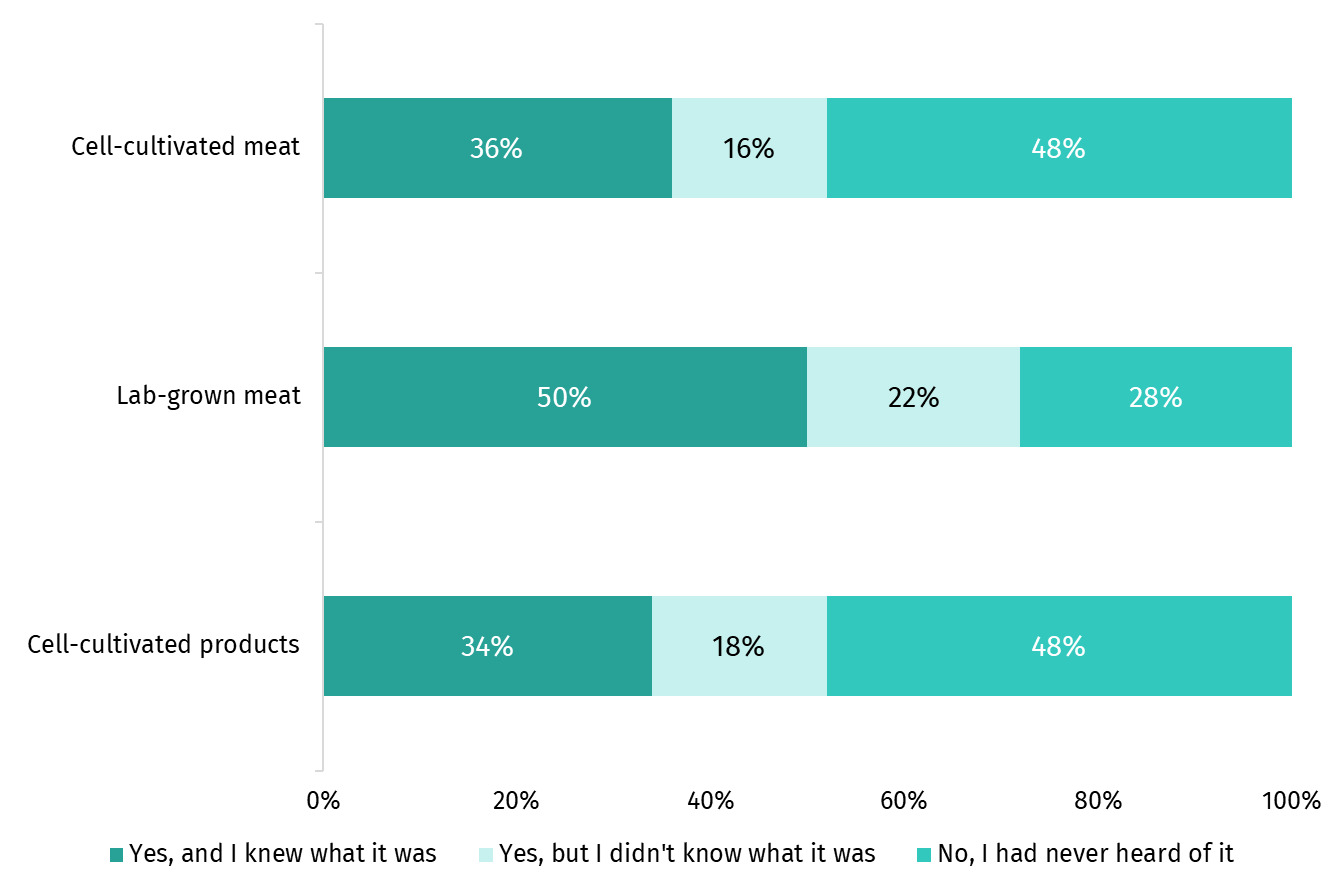

In October 2024, respondents were more likely to have heard of the term ‘lab-grown meat’ (72%), compared to ‘cell-cultivated products’ and ‘cell-cultivated meat’ (both 52%). Around a quarter (26%) said they would be willing to include cell-cultivated meat in their diet in the future, whilst over half (58%) said they would not be willing to include it in their diet.

In December 2024, one in eight (12%) respondents said they had used or consumed products containing cannabidiol (CBD) in the last 6 months. Of these, one in three (33%) said that they typically consume 1-10mg when they have CBD, in line with the FSA’s recommendation that healthy adults should limit their consumption of CBD to 10mg per day.

Introduction

Background

The Consumer Insights Tracker is the FSA’s monthly survey that monitors changes in consumers’ behaviour and attitudes in relation to food. The survey is conducted with consumers across England, Wales and Northern Ireland and covers a range of food-related topics that are of strategic interest to the FSA. This includes concerns about food-related issues, perceptions of the food supply chain, and attitudes and behaviours relating to food affordability and availability. The survey also covers a range of additional topics on an ad-hoc basis, such as novel foods (e.g. CBD) and food production techniques (e.g. precision breeding, cell-cultivated products). A full list of the additional topics covered from April 2024 to March 2025 can be found in Appendix A.

The FSA has been conducting monthly surveys since April 2020, when the FSA established the COVID-19 Tracker to monitor attitudes and behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic. This survey was designed to provide more regular and timely insights than the FSA’s official statistic survey, Food and You 2 (F&Y2)[1]. In April 2022, the survey was renamed the Consumer Insights Tracker. YouGov were appointed as the supplier of the Consumer Insights Tracker from July 2023.

The purpose of the Consumer Insights Tracker is to provide the FSA with regular, up-to-date information on topics of strategic interest. The regularity of data collection (monthly) allows for the monitoring of trends over time and helps to identify emerging issues. The data gathered informs policy decisions, helps prioritise areas for further research, and supports the development of communication campaigns.

This report presents key findings over the past year (April 2024 to March 2025). Where appropriate, charts and analysis also highlight longer-term trends over the full tracking period (from July 2023).

Wider context

Since 2022, the cost of living has risen both in the UK and across the world. The period during which this survey series took place (since July 2023) coincides with an easing cost-of-living crisis in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Inflation fell in the first half of the tracking period (March - September 2024) before rising again in March 2025 according to the ONS. In this period food price inflation was slightly lower than overall inflation and remained stable throughout the period mentioned in this report (April 2024 – March 2025). This indicates food prices were not a notable contributor to overall inflation. The stabilisation of food price inflation follows a period of high inflation over the previous two years.

Another significant event during the survey period was a general election on the 4th of July 2024, with major parties including food affordability, healthy and sustainable diets, and children’s diets in their manifestos. The new Government introduced legislation to limit junk food advertising to children which will come into force in October 2025.

Discussion around ultra-processed foods (UPFs) continued, and the FSA published consumer information on UPFs in May 2024 and a scoping review of consumer understanding and awareness in October 2024. These foods include cereals, biscuits, ham, sausages, bread and crisps (amongst others). The UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) has launched a public dialogue to gather opinions on ultra-processed foods to help shape research and policy on UPFs.

Several food recalls and allergy alerts were also issued over the period, for example an outbreak of E. Coli linked to prepackaged sandwiches and salads (May – July 2024) and urgent precautionary allergy advice for those who have a peanut allergy to avoid consuming foods that contain or may contain mustard, mustard powder or mustard flour because they may have been contaminated with peanuts (September – November 2024).

It is possible that some of these events may have impacted on consumers’ views towards food and attitudes towards the food system more broadly.

Method

The Consumer Insights Tracker is carried out monthly among a representative sample of approximately 2,000 people aged 16 and over living in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. All respondents who take part in the survey are drawn from the YouGov panel of over 400,000 active panel members who live in the UK.

The sampling approach used is quota sampling, with quotas taken from the 2021 Census. The sample for each wave is representative of the England, Wales and Northern Ireland population by age, gender, social grade, region and education level. A sample boost is also applied in Northern Ireland (achieving 100 respondents each month), to improve the representation of this group and to enable rudimentary demographic comparisons between countries. Once fieldwork has been completed, weighting is applied so that the sample more accurately reflects the demographics of the target population by age, gender, social grade, region and education level.

Full details of the methodology can be found in the Technical Report.

Notes for interpretation

This report focuses on insights from April 2024 to March 2025, with reference to longer term trends over the full tracking period (from July 2023) where appropriate. Differences across key demographic groups are also highlighted. The Consumer Insights Tracker uses t-tests to assess differences over time and between groups, and highlights those where the p value is <0.05. Due to the quota sampling methodology used, the tests cannot be interpreted strictly. However, they do help to highlight where there is the greatest evidence of a shift in behaviour or attitudes.

Key demographic variables analysed throughout this report include gender, age, ethnicity, region, whether there is a child aged under 18 living in the household, whether the person is limited by a health condition or disability and the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) decile (see further information in the Appendix B).

It should also be noted that there are some limitations of the online methodology used as part of this survey. For example, panel members on opt-in panels may be more engaged in current issues, which means they are more motivated to opt-into panel surveys. This means measures for some attitudes and behaviours may not truly reflect the total population. Additionally, some groups are underrepresented in online opt-in panels, for example those who do not have internet access or who are not comfortable going online, who also tend to be older and in lower socio-economic groups.

YouGov’s large nationwide panel which the survey sample is drawn from acts to mitigate these impacts, by enabling data to be gathered that is representative of the population in England, Wales and Northern Ireland across a range of demographic characteristics. In addition, the online methodology helps to reduce certain forms of bias (such as social desirability bias) compared to alternative survey methods, which can ensure that results better reflect people’s true behaviours and beliefs.

Further information about the research strengths and limitations are available in the Technical Report.

Detailed findings

This research explores perceptions among respondents across England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Concerns about food

What were respondents most concerned about in relation to food?

The price of food has consistently been the most common prompted concern since July 2023. There has also been little variation among the other top concerns. For instance, between April 2024 and March 2025, the most common prompted concerns among respondents were food prices (ranging from 86% - 88% reporting concern[2]), followed by ultra-processed, or the over-processing of, food (76% - 78%), the healthiness of diets in general (71% - 75%), and food poverty and inequality (72% - 76%).[3]

However, in the past year, concern about ingredients and additives in food (70% - 73%) became a more prevalent concern than animal welfare (68% - 72%) which was previously the fifth most common concern between July 2023 and March 2024. Although there was not a significant difference in the proportion of respondents reporting concern about ingredients and additives in food or about animal welfare between April 2024 and March 2025, there were some fluctuations throughout the year. The proportion reporting concern about ingredients and additives in food rose slightly from 70% in April 2024 to 73% in June 2024, remaining consistently one – five percentage points higher than animal welfare each month over the past year.

Who was most concerned about food prices?

Among respondents, there have been high levels of concern about food prices across all demographic groups since April 2024. Concern was slightly higher among women than men (March 25: 91% vs. 83%), without any other notable differences by demographic subgroup. Similar to the previous year, concern for food prices for almost all groups across the year was higher than 80%.

Who was most concerned about food poverty and inequality?

Concern about food poverty and inequality was also high (ranging from 72% to 78%), though concern was higher among:

-

Women (78% vs. 65% of men)

-

Respondents from an ethnic minority background (78% vs. 71% of White respondents)

-

Respondents with higher educational attainment (77% of those with a degree or higher vs. 71% of those with A levels as their highest educational attainment and 67% of those with GCSEs as their highest educational attainment)

Who was most concerned about ultra-processed, or the over-processing of, food?

High levels of concern were also reported about ultra-processed, or the over-processing of, food in March 2025. Those most concerned were:

-

Respondents in older or middle age groups (82% of those aged 55+ and 78% of those aged 35-54 vs. 72% of those aged 16-34)

-

Respondents with average or higher educational attainment (83% of those with a degree or higher and 81% of those with A levels as their highest educational attainment vs. 68% of those with GCSEs as their highest educational attainment)

-

Respondents in Wales (86% vs. 78% in Northern Ireland and 77% in England)

Household food affordability and risky food behaviours

Respondents were also asked a series of questions relating to their perceptions and experience of food affordability and whether they had engaged in specific food-related behaviours. They were asked to consider both themselves personally and their household when answering these questions.

How have worries about food affordability changed over time?

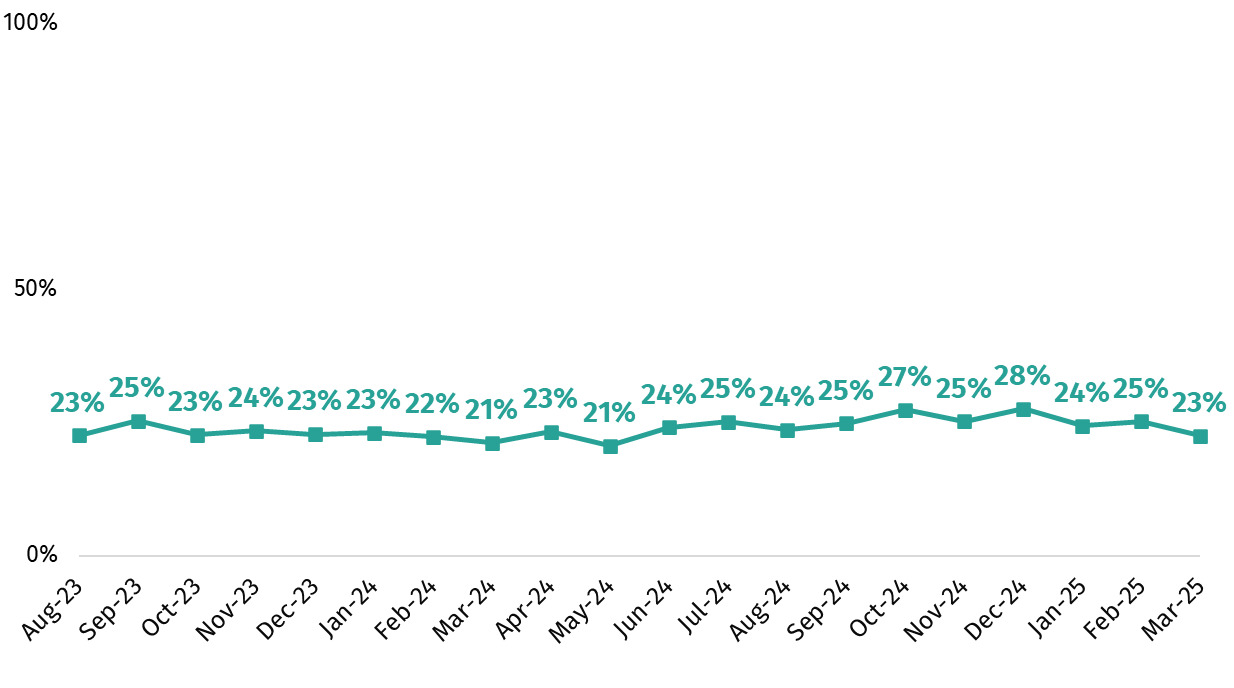

There has been a slight decline between April 2024 (24%) and March 2025 (21%) in the proportion of respondents reporting they are worried[4] about being able to afford food in the next month, representing a longer term downward trend from July 2023 (28%).

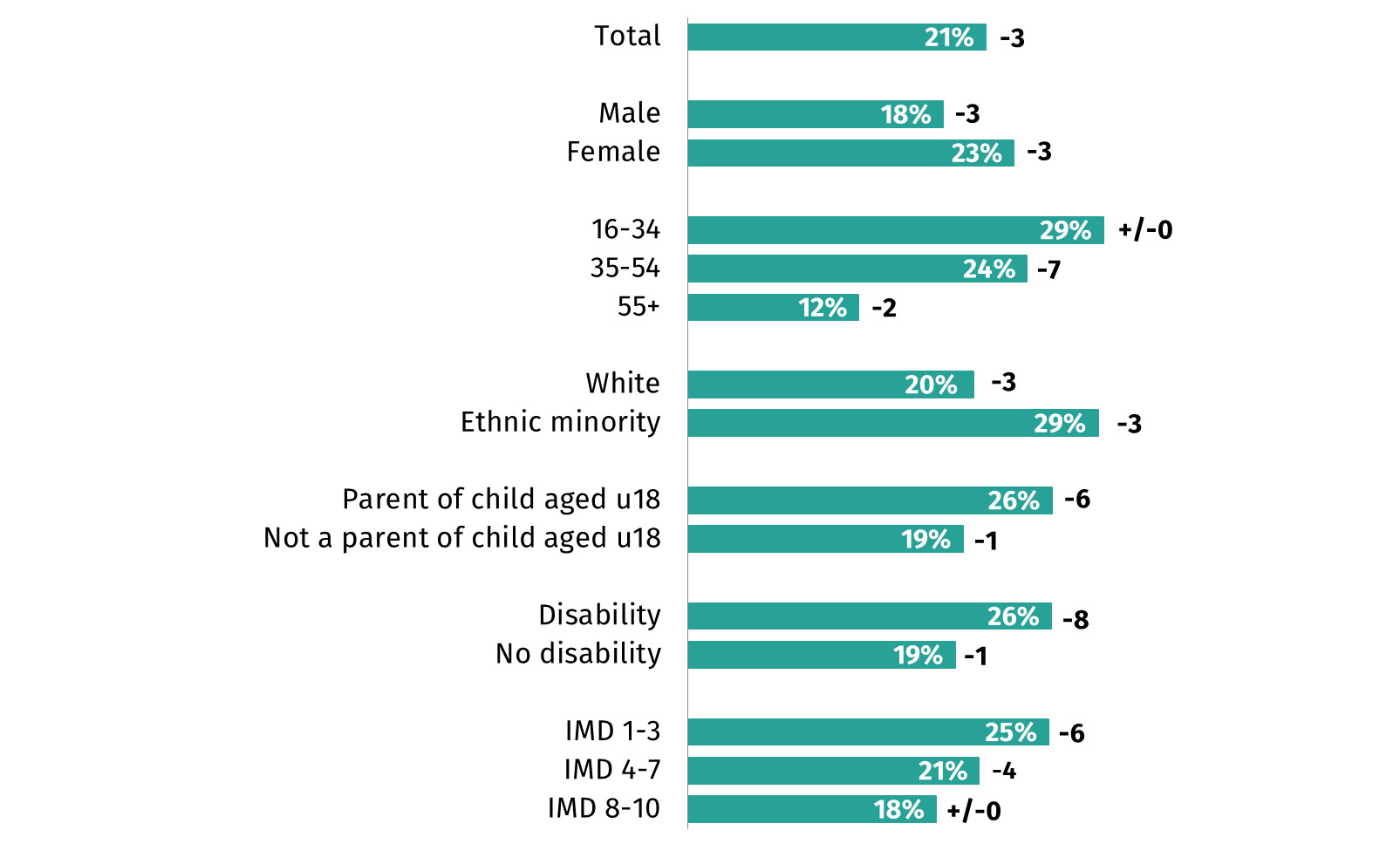

In March 2025, one in five respondents (21%) reported feeling worried about themselves personally or their household being able to afford food in the next month (Figure 2), compared to a quarter (24%) in April 2024.

Who was most worried about food affordability?

Respondents who are younger (16-34 - 29%), from an ethnic minority background (29%), parents (26%), have a disability or long-term health condition (26%) and living in the most deprived IMD deciles (1-3 - 25%) were the most likely to report being worried about food affordability in March 2025 (Figure 3).

These groups were consistently the most worried about food affordability between April 2024 and March 2025 although there has been some change over time since April 2024 (as shown on Figure 3).

While overall concern about food affordability has slightly decreased, Figure 3 shows greater decline among some groups that were previously more worried about food affordability. Among respondents with a disability or long-term health condition worry has decreased by 8 percentage points (pp), and it has decreased 6 pp among parents and those who live in the most deprived IMD areas. [5] However, among other groups there has been no change. For example, among respondents aged 16-34 there was no decline (0pp) and a non-significant decline among respondents from an ethnic minority background (-3pp).

How have shopping, cooking and eating behaviours changed over time?

Across nearly all food shopping behaviours to save money, there has been a decline in the proportion reporting these behaviours from April 2024 to March 2025 (Figure 4). The proportion of respondents who reported choosing cheaper alternatives has declined from 51% in April 2024 to 44% in March 2025. Similarly, the proportion who reported buying reduced foods has decreased from 42% in April 2024 to 34% in March 2025. There has been a similar decrease in shopping for food in multiple supermarkets (36% to 30%). However, the proportion who bought less fresh food and more long-life foods instead to save money has remained relatively stable at 19% in April 2024 and 16% in March 2025.

Respondents who were worried about their or their household’s ability to afford food in the next month were more likely to report a number of shopping behaviours to save money than those who were not worried about food affordability (Figure 5). Most notably, those who were worried about food affordability (41%) were more likely to report buying less fresh food compared to those who were not worried (9%). There were also differences in the proportion who chose cheaper alternatives rather than branded products (58% of those worried vs. 40% of those not), bought discounted food (46% vs. 32%) and shopped for food in multiple supermarkets (36% vs. 29%). These differences were consistent over time.

Furthermore, there were differences in the proportion who reported not being able to afford to buy food that meets their animal welfare or environmental standards (15% vs. 3%) and not being able to afford their essential food shopping (14% vs. 1%).

While there has been some reduction in the proportion reporting the above money saving shopping behaviours, there has been no change in most of the cooking and eating behaviours asked about apart from a decline in the proportion reporting cooking something from scratch (41% in April 2024 vs. 37% in March 2025). There were no significant changes in the proportion reporting they had used cheaper cooking methods (57% in April 2024 vs. 54% in March 2025), bulked out meals with cheaper ingredients (17% vs. 15%), could not afford to eat a healthy diet (10% vs. 9%) or cut the size of meals or skipped them entirely (10% vs. 8%).

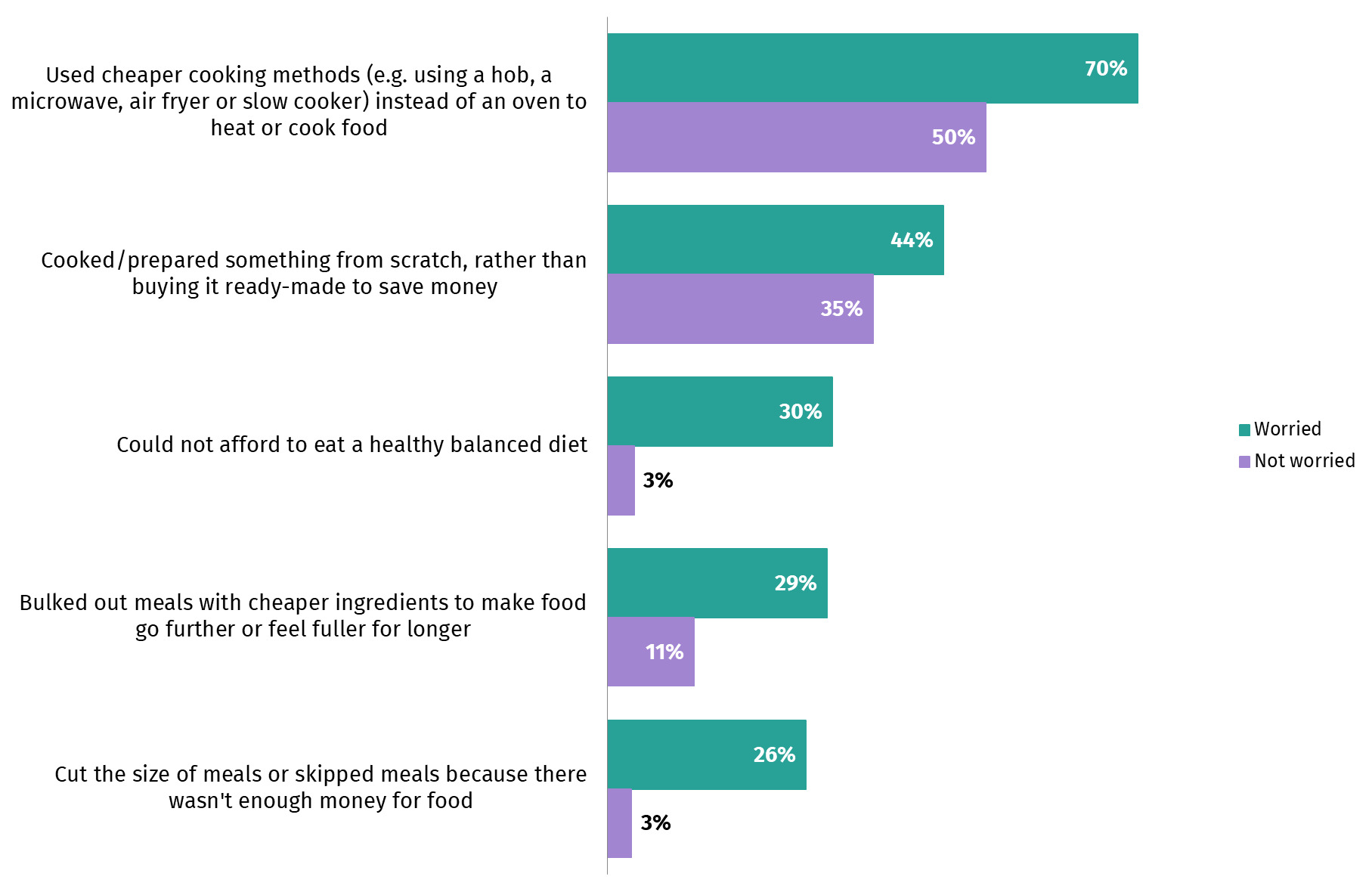

As with shopping behaviours, respondents who were worried about food affordability were more likely to engage in all of these cooking and eating behaviours. Those who were worried were most likely to have used cheaper cooking methods (70% vs. 50% who were not worried) and prepared something from scratch rather than buying it (44% vs. 35%). This was followed by not being able to afford a healthy balanced diet (30% vs. 3%), bulking out meals with cheaper ingredients (29% vs. 11%) and cutting the size of, or skipping, meals (26% vs. 3%).

Has trying to save money led people to practice potentially risky food behaviours?

Respondents were asked whether they had taken a number of potentially risky food-related actions in the last month in order to reduce their energy bills and save money. These included reducing the length of time food is cooked for; lowering the cooking temperature for food; turning off a fridge/freezer containing food; changing fridge/freezer settings to a warmer temperature; or eating food cold because they could not afford to cook it.

When grouping these behaviours together, the proportion of respondents who said they engaged in at least one of these behaviours was 23% in March 2025. Although this is comparable to April 2024 (23%), there have been some fluctuations in the proportion reporting at least one of these behaviours each month between April 2024 and March 2025. For example, between April and December 2024, the proportion who reported at least one behaviour rose from 23% to 28%, decreasing again to 23% in March 2025.

Figure 8 shows that in March 2025, the most common reported behaviour was lowering the cooking temperature for food (13%), closely followed by reducing the length of time food is cooked for (12%). One in nine (11%) said they changed the setting of their fridge/freezer so food is being kept at a warmer temperature and 7% reported turning off a fridge/freezer that contains food.

In addition to being asked about what they had done to reduce their energy bills and save money, respondents were also asked whether they or someone in their household had eaten food past its use by date because they couldn’t afford to buy food. In March 2025 9% of respondents reporting doing this, a decrease from 12% in April 2024.

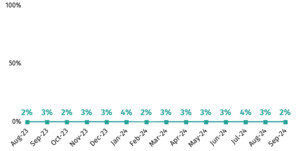

How has food bank usage changed over time?

Between August 2023 and September 2024, respondents were asked whether they or anyone in their household had used a food bank in the last month. The proportion of respondents who reported using a food bank in the last month remained consistent between August 2023 and September 2024 (2% - 4%) (Figure 9).

The relatively low incidence of food bank usage makes it more difficult to detect statistically significant differences across demographic groups for individual months. However, combining the data from July to September of 2024 revealed specific groups were more likely to have used a food bank:

-

Younger respondents (6% of 16-34s vs. 2% of 35-54s and 1% of 55+)

-

Respondents from an ethnic minority background (8% vs. 2% of White respondents)

-

Respondents who are parents of children under 18 (4% vs. 2% of those without children)

-

Respondents in the most deprived IMD deciles (4% 1-3 vs. 2% of 8-10, the least deprived)

-

Male respondents (4% vs. 2% of women)

Food availability

How have worries about food availability changed over time?

Respondents were asked how worried they are about there not being enough food available for themselves or their household in the next month. The proportion who are worried has remained largely consistent over time (19% - 24%). There was a small increase in the proportion who were worried in December 2024 (24%) however this returned to more typical levels in January 2025 (19%).

Who was most worried about food availability?

Groups most worried about food availability in March 2025 included[6]:

-

Respondents in younger and middle age groups (28% of 16-34s and 22% of those aged 35-54 vs. 9% of those who are 55+)

-

Respondents from an ethnic minority background (30% vs. 17% of White respondents)

-

Respondents who are parents of children under 18 (25% vs. 16% without children)

-

Respondents with a disability or long-term health condition (24% vs. 16% without one)

Confidence in the food supply chain

How has confidence in the food supply chain changed over time?

Across the past year, overall confidence[7] in the food supply chain has stayed broadly stable with around six in ten respondents reporting confidence. Confidence is slightly higher in March 2025 (63%) than in April 2024 (59%) and when tracking began in July 2023 (55%). The proportion of respondents who said they were not confident has fallen slightly since April 2024, from 28% to 23% in March 2025. There was a period of stability in the second half of 2024, before this declined at the start of 2025.

Across all months from April 2024 to March 2025 and since tracking began, confidence was consistently highest in those involved in the food supply chain ensuring that food is safe to eat (74% in March 2025). Around six in ten reported being confident that those involved in the food supply chain ensure there is enough food available (63%), and that they ensure food is of high quality (60%). Levels of confidence relating to food availability and quality rose marginally by 6 and 5 percentage points, respectively, from April 2024 to March 2025, while confidence that those involved in the food supply chain ensure that food is safe to eat remained stable over the same period (Figure 12).

Confidence was lowest regarding food affordability, with 44% of respondents in March 2025 saying they were confident that those involved in the food supply chain ensure that there are affordable food options for everyone, with a similar proportion (45%) not confident. Confidence has increased in this area, rising from 34% in July 2023, however it remains consistently lower than the other aspects asked about.

Which groups expressed the lowest levels of overall confidence in the food supply chain?

In March 2025, the groups most likely to say they were not confident[8] in the food supply chain included:

-

Female respondents (27%), compared to 20% of male respondents

-

Respondents limited by a health condition or disability (28%), compared to 21% of those who are not limited

-

Respondents in Wales (36%), compared to 23% in England and 24% in Northern Ireland

Trust and confidence in the FSA

How many respondents reported knowing about the FSA?

Awareness of the FSA has been broadly stable over the past year (89% in both March 2025 and April 2024) and since tracking began in August 2023 (89%). In March 2025, over half (54%) of respondents stated that they have at least some knowledge of the FSA, though most of this group said they know ‘a little’ (50%), compared to just 4% who said they know ‘a lot’ (Figure 13). A further 34% reported that they had heard of the FSA but know nothing about it.

Self-reported knowledge of the FSA has been consistently higher among certain groups over time. In March 2025, respondents aged 55 and over (64% vs. 55% of those aged 35-54 and 40% of those aged under 35), white respondents (55% vs. 41% of those from an ethnic minority background) and those in social grades AB (58% vs. 46% in DE) were more likely to report having knowledge of the FSA. Male respondents were slightly more likely to report having knowledge of the FSA compared to female respondents (57% vs. 51%).

For the remainder of this section on trust, analysis is filtered to only include those with some knowledge of the organisation[9], as this is seen as a more reliable measure for tracking trust over time.

How has trust in the FSA changed over time?

Among those with some knowledge of the FSA and what it does, trust in the organisation has fluctuated since August 2023 (Figure 14).[10] The proportion of respondents that trust the FSA to do its job across the past year has ranged from 56% to 65% (the highest figure across the whole timeseries, reported in July 2024). The proportion who reported that they do not trust the FSA has been more consistent over time and remains low at 5% in March 2025. Therefore, the fluctuations in the proportion of respondents saying they trust the FSA is more a function of changes in the number of respondents saying they neither trust nor distrust the FSA, rather than changes in the numbers saying they distrust the FSA.

Which groups expressed lower levels of trust in the FSA?

Low proportions said they distrust the FSA with few notable differences between demographic groups. However, in March 2025, there were some groups less likely to say they trust the organisation, including:

-

Respondents aged 35-54 (67%) and those aged 55 and over (57%), compared to 73% of those aged 16-34

-

Respondents limited by a health condition or disability (55%), compared to 67% of those who are not limited

How confident were respondents in the FSA’s ability to carry out its functions?

Overall, there remains a high level of confidence in the FSA’s ability to carry out its functions. The proportion who are confident that the FSA takes appropriate action regarding food-related risks and who are confident that it can be relied upon to protect the public from food-related risks has been stable over time (Figure 15). In March 2025, around eight in ten respondents were confident that it takes appropriate action regarding food-related risks (79%) and that it can be relied upon to protect the public from food-related risks (77%) largely unchanged from August 2023 (77%, 78% respectively).

Confidence that the FSA is committed to communicating openly with the public about food-related risks was slightly lower, though remains a majority at 70%. This figure has remained generally in line with the 66% recorded in April 2024 but is currently on an upwards trend following a dip in December 2024 (64%).

Novel foods and food production techniques

The following section presents findings from a range of questions on novel foods and food production techniques. Unlike the questions presented so far, these questions are only included in the survey every 6 months. The findings presented for each topic relate to the most recent time those questions were asked (up to March 2025). These dates will vary for each topic.

How has awareness of precision breeding changed over time?

“Precision breeding” means a range of scientific techniques that make changes to a plant or animal that could have happened through traditional breeding, but can now be made to happen more quickly or more predictably. It has the potential to help create plants and animals that are more disease-resistant, require less water, and have higher nutritional value, amongst other outcomes.

In March 2025, one in seven (13%) respondents said they had heard of precision breeding before. This included 4% who know what it is and 9% who had heard of it, but did not know what it is. Awareness of precision breeding has fallen over time, from around one in six in March 2024 (17%) and September 2024 (18%).[11]

What was awareness of precision breeding by demographic groups?

Figure 16 shows awareness by demographic groups in March 2025, which is highest among younger respondents and those from ethnic minority backgrounds.

Did respondents think precision breeding is acceptable?

In the survey, respondents were shown a definition of precision breeding and then asked how acceptable or unacceptable they found its use in plants and animals. Overall, precision breeding of plants (43%) was more likely to be seen as acceptable than precision breeding of animals (26%) (Figure 17).

When thinking about precision breeding of plants, a higher proportion of respondents thought this was acceptable (43%) than unacceptable (22%) with a similar proportion not having an opinion either way (20%). [12]

When thinking about precision breeding of animals, a higher proportion thought this was unacceptable (42%) than acceptable (26%). A further 32% did not have an opinion either way or said they did not know (also Figure 17).

Had respondents heard of cell-cultivated products?

Cell-cultivated products cover a variety of foods that can be made using a production process without slaughter or traditional farming and agricultural practices. For example, cells isolated from animals (including cells from meat) can be grown in a controlled setting and then harvested to make a final food product. Cell-cultivated products produced from animal cells can also be known as ‘lab-grown meat’ or ‘cell-cultivated meat’. These products are not yet on the market in the UK for human consumption, however dog food made from these products has now gone on sale in the UK[13].

In the October 2024 survey, respondents were shown definitions of cell-cultivated products, lab-grown meat and cell-cultivated meat and asked whether they had heard of the terms before. Awareness of the term ‘lab-grown meat’ (72%) was higher than awareness of the terms ‘cell-cultivated products’ and ‘cell-cultivated meats’ (both 52%).

What did respondents think about the sale and consumption of cell-cultivated meat in the UK?

When thinking about the sale of cell-cultivated meat in the UK in the future, a higher proportion thought that it should not[14] be on sale in the future (46% vs. 31% who said it should be on sale). Nearly one in four (23%) were unsure.

Over half of respondents (58%) said that they would not be willing[15] to include cell-cultivated meat in their diet, whilst around a quarter (26%) said they would be willing to. Respondents who were more likely to say they would be willing to include cell-cultivated meat in their diet included young people (aged 16-34: 38%) and men (34%) (see Figure 19).

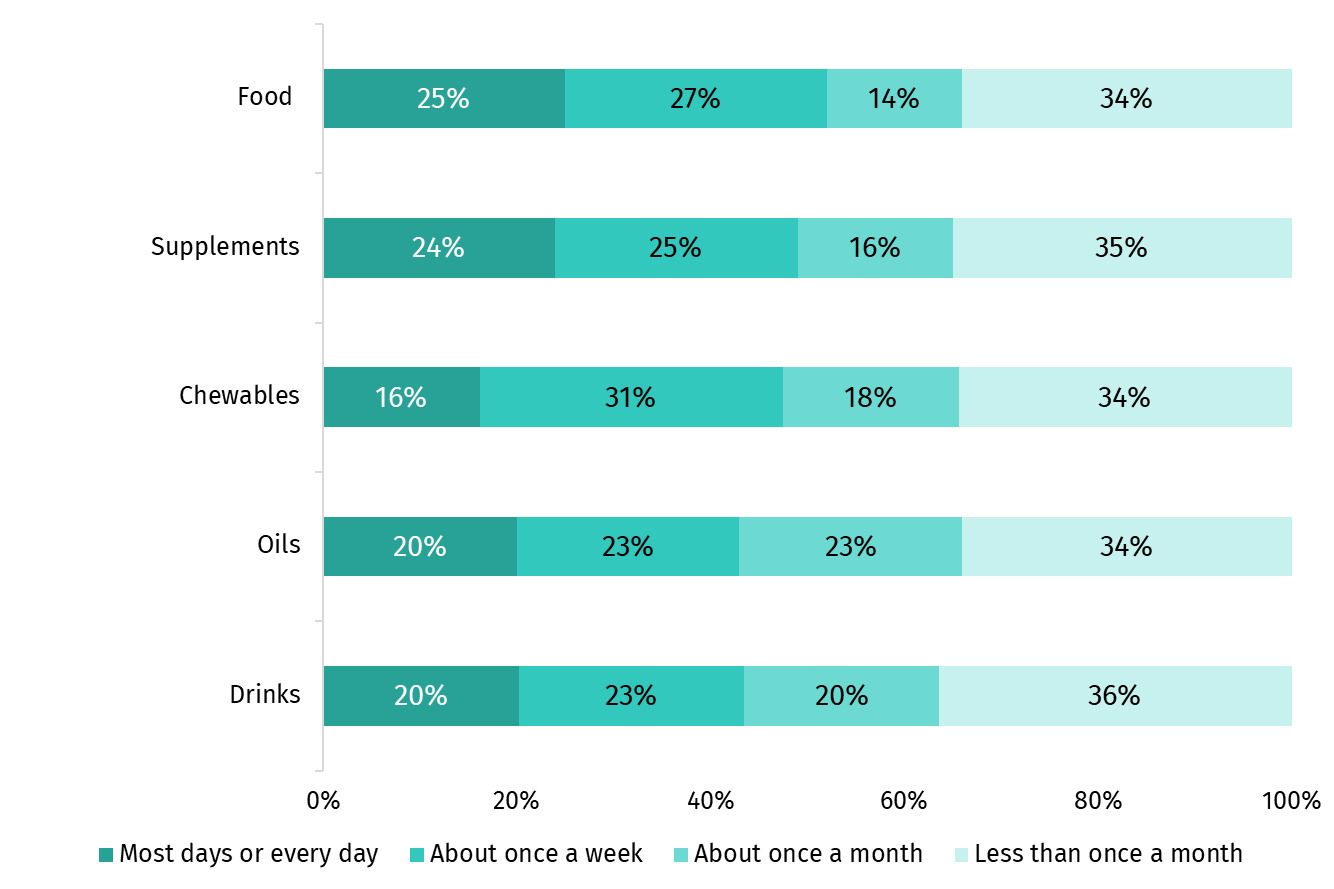

How often did respondents use products containing cannabidiol (CBD)?

Cannabidiol, commonly known as CBD, is an ingredient that is sometimes contained in food, drinks, supplements, oils or other products sold in the UK.

In December 2024, one in eight respondents (12%) said they had used or consumed products containing CBD in the last 6 months. This was highest among respondents in the younger and middle age brackets in comparison to those aged 55 and over (17% of 16-34s, 15% of 35-54s and 6% of those aged 55+). There were little differences in usage by other demographics.

Among those who recalled using or consuming each CBD product asked about, between 43% and 52% said they use them once a week or more. This includes CBD in food (52%), supplements (49%), chewables (48%), oils (44%) and drinks (43%).

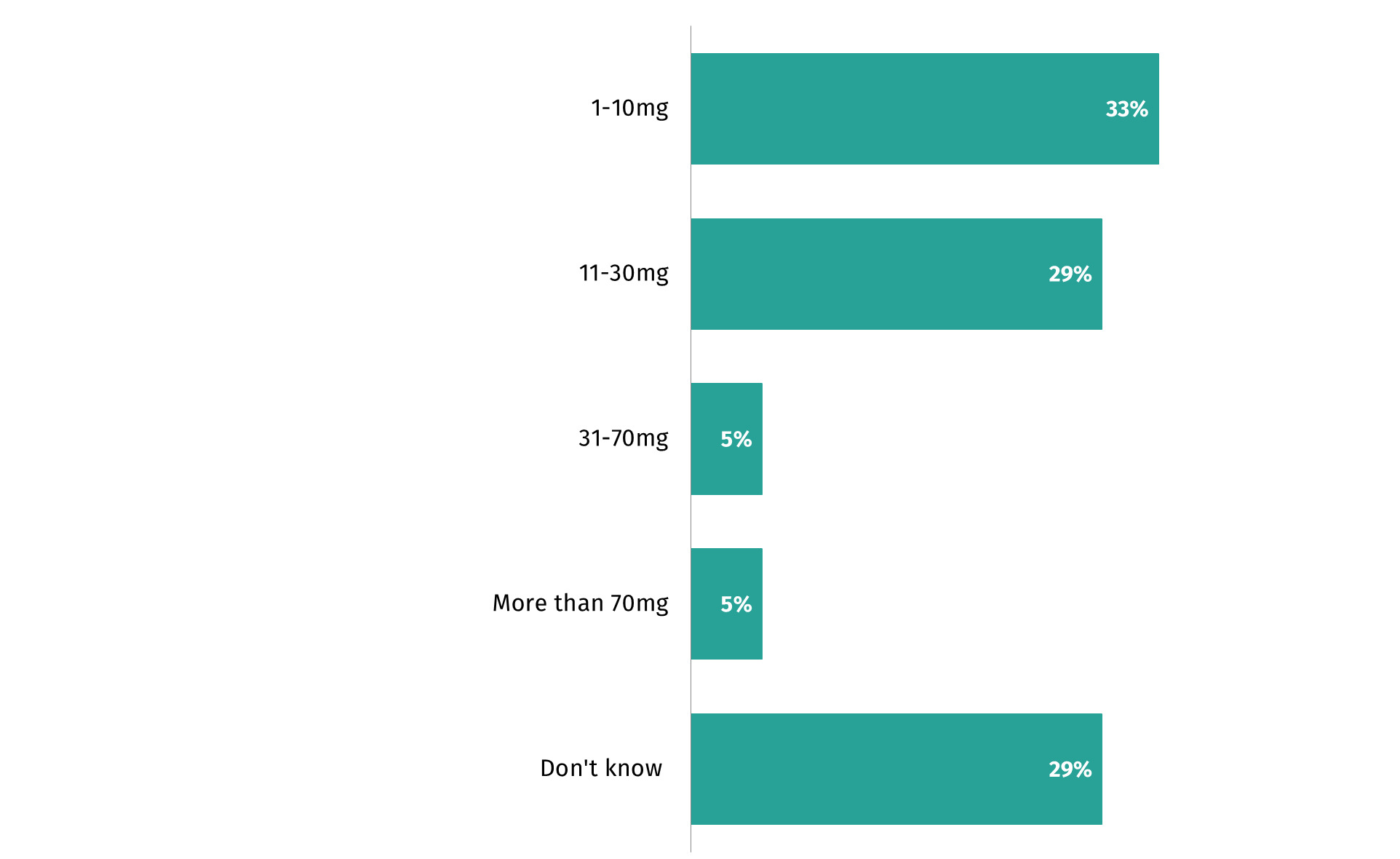

How did respondents say they determine and manage their CBD dosage?

In order to determine what a suitable dose of CBD is, most commonly respondents said they follow the instructions on the label (53%), monitor the effect it has on them and increase/reduce the dose as desired (33%) or research about the topic on the internet (31%). One in six (17%) said they use information from the FSA’s public list of CBD products and a similar proportion (15%) said they follow the FSA’s daily consumption advice.

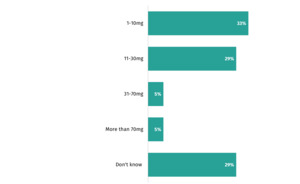

The FSA recommends that healthy adults should limit their consumption of CBD from food to 10mg per day, which is about 4-5 drops of 5% CBD oil.[16] One in three (33%) said that they typically consume 1-10mg when they have CBD, in line with these recommendations. Just under two in five (38%) consume more than this and around three in ten (29%) said they didn’t know how much they would typically consume in a day.

Discussion

The cost of food continues to be the top concern for the vast majority of respondents. This likely reflects the ongoing financial pressures of the cost-of-living crisis, with food prices being the top concern since April 2024 and since tracking began in July 2023. Food poverty and inequality has also remained one of the top five concerns over the last year. While general concern for food prices remains high, when thinking about their personal situation, there has been a slight decline in the proportion of respondents who said they were worried about themselves or their household being able to afford food in the next month. This provides an indication that the situation might be easing slightly for some.

The level of concern about different issues varies by demographic group. For instance, respondents from an ethnic minority background report higher concern for two of the top five concerns: food poverty and inequality and ingredients and additives in food. Meanwhile, several other demographic groups report higher concern for two of the top five topics including women, respondents who are younger and middle aged, those with a higher educational attainment, parents and those limited by a long-term health condition/disability. This pattern suggests that certain demographic groups may experience or perceive food related concerns more acutely than others.

Within the context of continuing debate and discussion around ultra-processed foods (UPFs), concerns around these foods continue to be reflected in the data from the Tracker. Two of the top five prompted concerns from April 2024 to March 2025 relate to ingredients/additives and processing of food. UPFs remain the second highest concern among respondents from April 2024 to March 2025, with nearly four in five concerned about these foods in March 2025.

Analysis of the behaviours of respondents since April 2024 suggests some other changes to behaviour. Respondents are now less likely than they were in April 2024 to report doing nearly all of the money saving shopping behaviours asked about in the Tracker. This decrease in prevalence is also reflected among those who said they were worried about food affordability, indicating that behaviour is changing across a range of respondents. However, this trend does not continue to all cooking and eating behaviours asked about. For instance, respondents were no less likely in March 2025 than they were in April 2024 to report partaking in potentially risky cooking and eating behaviours to save money on their energy bills. It is unclear why this might be the case. This could be linked to the question wording as some of the cooking and eating behaviours are asked in relation to energy bills, while shopping behaviours are asked generally. This could also be a reflection that food shopping is seen as a way to save money, while cooking and eating are not.

In general, the proportion who reported engaging in potentially risky cooking and eating behaviours has fluctuated (21%-28%) between April 2024 and May 2025. The highest proportion of respondents who reported engaging in these behaviours was in December 2024 (28%). This could be a result of increasing financial pressures in the lead up to Christmas, however this same fluctuation was not reported in 2023.

Trust and confidence in the FSA have remained high over the past year. Trust in the FSA fluctuated over a small range (56% to 65%) over time, whilst distrust remained consistently low. The highest level of trust was seen in July 2024. Fieldwork in July took place immediately after the general election of July 4th (July 5th-9th). Close to four in five of those with knowledge of the FSA were confident in its ability to take appropriate action on food related risks, while over three quarters thought the FSA can be relied upon to keep the public safe.

Data collected in relation to novel foods and food production techniques suggest awareness of different terms varies by processes and terminology used. For example, in October 2024, around seven in ten said they had heard of lab-grown meat, but only around half had heard of cell-cultivated products and cell-cultivated meats. Furthermore, in March 2025, only one in eight respondents said they had heard of precision breeding before. The research also suggests that most respondents are not following the FSA’s recommendations regarding CBD consumption, with only one in three respondents who consumed CBD reporting they typically consume 1-10mg per day.

Appendices

Appendix A – Additional topics (April 2024 – March 2025)

Table 1 provides a summary of the additional topics included in the Consumer Insights Tracker from April 2024 – March 2025. Please note not all these topics are covered in this end of year report. To access data for any topic, you can download the Consumer Insights Tracker data tables for the specific month that topic was included.

A full list of questions is included within the technical report.

Appendix B – Definitions

Definitions

Definitions of the IMD and social grade are provided below.

-

The Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) is calculated using country-specific metrics (domains of deprivation), such as income, barriers to housing and services and crime, which are combined to give an overall measure of relative deprivation within a respondent’s specific output area. These output areas are then ranked and within the report are grouped so that comparisons are made between those in the most deprived (1-3), middle (4-7) and least deprived (8-10) IMD deciles.

-

England: The IMD ranks each English LSOA (Lower layer Super Output Areas) from 1 (most deprived) to 32,844 (least deprived)

-

Wales: The Welsh equivalent (WIMD; Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation) ranks each Welsh LSOA from 1 (most deprived) to 1,909 (least deprived)

-

Northern Ireland (NI): The NI equivalent ranks each OA (Output Area) from 1 (most deprived) to 5,022 (least deprived)

-

- Social grade is a socio-economic metric classification which groups people into four classifications based on “the occupation of the Chief Income Earner (CIE)” of their household[17]. This report compares those in social grades AB, C1, C2 and DE as classified by the National Readership Survey (NRS).

The way in which social grade is classified is listed below:

-

AB: higher and intermediate managerial, administrative and professional occupations

-

C1: supervisory, clerical, and junior managerial, administrative and professional occupations

-

C2: skilled manual occupations

-

DE: semi-skilled and unskilled manual occupations, unemployed and lowest grade occupations

Food and You 2 was conducted biannually (twice a year) until 2025, and annually from May 2025

Either ‘highly’ or ‘somewhat’ concerned

The survey prompted respondents with a list of 14 different food related concerns and asked them how concerned, if at all, they were about each of them

Either ‘very’ or ‘somewhat’ worried

The sample size for some of these subgroups vary. While the differences presented for March 2025 are significant using t-tests at p<0.05, fluctuations have been noted among some of these groups wave on wave.

Note that findings among young people and those from ethnic minority backgrounds could be linked, given those from ethnic minority backgrounds have a younger age profile than White adults. See Gov.UK Census 2021 Age Groups

Either ‘very’ or ‘fairly’ confident

Either ‘not very’ or ‘not at all’ confident

Either ‘a lot’ or ‘a little’ knowledge about the FSA and what it does

Either ‘trust it a lot’ or ‘trust it’

Either ‘yes, and I know what it is’ or ‘yes, but I don’t know what it is’

Acceptable is either ‘very’ or ‘fairly’. Unacceptable is either ‘fairly’ or ‘very’.

Should not is either should ‘probably not’ or ‘definitely not’. Should is either should ‘definitely’ or probably’.

Willing is either ‘very’ or ‘somewhat’ willing. Not willing is either ‘somewhat’ or ‘very’ unwilling.

FSA: ‘Cannabidiol (CBD)’ (link here)

National Readership Survey: ‘Social Grade’ (link here.)

.png)

.png)