1. Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank all of the allergy organisations for their efforts in promoting this study for recruitment: Allergy UK, Anaphylaxis UK, Coeliac UK and the Natasha Allergy Research Foundation. Thanks also go to the research assistants who helped with running cognitive interviews of the survey, building the survey on Qualtrics and preparing the data to be included in this report: Cassie Screti, Caity Roleston and Gurkiran Birdi.

2. Executive Summary

2.1. Introduction

This report presents findings from research conducted by Aston University on behalf of the Food Standards Agency (FSA). The FSA is the independent government department responsible for protecting public health and consumers’ interests in relation to food across England, Wales and Northern Ireland. The FSA is responsible for allergen labelling, and for providing guidance to consumers with food allergies, food intolerances or coeliac disease (referred to collectively as food hypersensitivities (FHS)). This includes working with consumers and the food industry to ensure consumers with FHS can make safe and informed choices. Eating a food which you are sensitive to, can result in an adverse reaction with unpleasant and sometimes life-threatening symptoms. Management of FHS therefore involves individuals being aware of risks and determining if a food is safe to eat.

The objective of this research was to understand the circumstances that could lead to reactions and near misses to food or drink in people with FHS. This research explores the reactions and near misses that have taken place in the last five years in adults and children with either self or medically diagnosed FHS, in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Findings will add to the evidence base in this area and inform the FSA’s food hypersensitivity programme.

Specific research aims were to:

-

Characterise reactions and near misses. For example, the type of business the food was purchased from and what type of food was involved (loose or packaged).

-

Understand the ‘journey’ which resulted in a reaction or near miss. For example, how the food was purchased and the provision of allergen information and disclosure of FHS.

-

Identify the self-reported cause(s) of reactions and near misses.

2.2. Methodology

Two online surveys were conducted between 28 February and 27 March 2023 - one for parents of children with FHS aged 0-17 years and one for adults with FHS aged 18 years and over. All participants were living in England, Wales or Northern Ireland. Those living in Scotland were excluded as the FSA does not have responsibility for food allergen labelling in Scotland (this is under the remit of Food Standards Scotland). All participants (or their child in the case of parents) had experienced a near miss or reaction to food or drink in the last five years. The questions in the survey related to the last reaction or near miss that the individual had experienced.

The following definitions are used throughout this research:

-

Food Hypersensitivity (FHS): Collective term for food allergy, food intolerance and coeliac disease, defined as experiencing a physical reaction after consuming certain foods.

-

Reaction: Experiencing physical symptoms due to eating or drinking something, due to a food hypersensitivity

-

Near miss: Buying, ordering or receiving food or drink that the consumer believed did not contain any ingredients they had a hypersensitivity to. However, the food or drink received did contain the ingredient/s and the consumer: a) noticed this before eating the food or drink; or b) ate the food or drink and did not have a reaction (physical symptoms due to their allergy, intolerance or coeliac disease).

-

Incident: A collective term for reactions and near misses.

-

Packaged food: Food already in packaging when selected/ordered. This includes prepacked (placed in packaging by another business such as crisps and ready meals) and prepacked for direct sale food (PPDS) (placed in packaging by the same businesses on the same site such as grab and go sandwiches).

-

Loose food: Food that is not in packaging when selected/ordered such as meals in a café/restaurant or loose cheese on a deli counter.

A non-probability opportunity sample was recruited, which means consumers with FHS were invited to participate in this research through convenience sampling. This means that individuals were recruited because of their suitability for the research. The research was advertised via allergy organisations’ newsletters and social media, FSA social media (Twitter and Facebook) and a further section of the sample were recruited using an online survey panel. Recruitment content included requests for snowball sampling - participants being asked to recruit further participants through their contacts, network groups and acquaintances. The study did not recruit a weighted or representative sample as the demographic spread of the FHS population in the UK is currently unknown.

A total of 676 adults with FHS and 425 parents of children with FHS completed the surveys. The sample includes participants with food allergies, food intolerances, and coeliac disease. Further detail on the demographic characteristics of this sample can be found in Chapter 4.

To be eligible, participants were required to have experienced a FHS incident (including both reactions and near misses) in the last five years. Participants were then asked to consider their most recent FHS incident when answering questions. The majority of both adults (81%) and parents (87%) reported on an incident that had taken place in the last year. Just under three-quarters (73%) of adults, and around two-thirds of parents (65%) reported a FHS reaction.

Further information on the methodology of this research is available in Chapter 4, as well as in the accompanying technical report available on the FSA website.

2.3. Summary of discussion of FHS incidents

When interpreting this research, it is important to consider the findings in light of the sample of participants involved; those who have had either a reaction or a near miss in the last five years. It should also be noted that responses relating to loose food are skewed towards incidents which occurred in restaurants, and to a lesser extent cafés and will therefore likely reflect the consumer ‘journey’ when purchasing food at these types of places.

Overall, this research found that the majority of adults (75%) and parents (83%) who reported an incident in relation to loose food in the last five years had been provided with some form of allergen information at the point of ordering. This research also found that the majority of consumers (82% of both adults and parents) reported disclosing their FHS requirements. Despite this, these consumers still reported experiencing FHS incidents in the past five years, which indicates that additional problems are occurring throughout the service journey.

Potential problems throughout the journey include information provision, communication and cross-contamination. Participants who experienced an incident with loose food most commonly attributed it to cross-contamination (25% of adults and 27% parents). However, as with all of the causes reported by consumers in this survey, this cross-contamination cannot be verified. It is possible that consumers attribute their incident to this where the genuine cause of the problem is not easily identifiable to them (therefore the assumption is that it was due to cross-contamination).

Whilst the survey captured cross-contamination as a cause, the focus of the survey was on information provision and communication, therefore the content of the discussion focuses on these aspects. This includes consumer disclosure and provision of information on the occasion of the incident as well as possible communication issues within food businesses, alongside other staff errors (as reported by consumers).

The discussion primarily reports on the experiences of consumers when purchasing loose food, as this was the primary aim of this research. Data was also collected on consumers who reported that their most recent incident was to packaged food (which includes PPDS and prepacked foods), however there is less detailed insight due to it being a secondary objective.

2.3.1. Consumer reports of business behaviour on occasions where there were FHS incidents to loose food

Provision of Information (POI)

FBOs are required to provide accurate allergen information on the 14 regulated allergens available to consumers.[1] This can either be verbally (with a sign indicating where the information can be obtained) or in writing and they do not have to provide it proactively. This research indicates that, overall, consumers did not commonly report a total absence of allergen information, and few attributed an unfulfilled request to provide information as a cause of their reaction.

The findings on provision of information rely on the accurate recall of consumers. In some situations, it is possible that allergen information would only be provided on request, which means that if consumers didn’t ask the FBO for this information, they wouldn’t receive this.

Allergen information was provided to customers (who were involved in ordering) in either written and/or verbal format in the majority of incidents reported in this survey (75% of adults and 83% of parents).[2] 38% of adults and 46% of parents reported that allergen information was provided verbally, and only 17% of adults and 16% of parents reported that allergen information was not visible. Only 4% of adults and parents reported that allergen information was not provided in response to a query.

In terms of consumers reporting the provision of information as a cause of their FHS incident, only 3% of adults and no parents reported that the cause of their incident was due to asking for allergen information, but that this was not provided by the FBO.

Although 15% of both adults and parents reported that the cause of their incident was due to there being no ingredients list provided, it is not a legal requirement for FBOs to provide consumers with this information for loose foods.

Business error

Many consumers felt that staff errors were causal to their FHS incidents. Only participants who knew that they had a FHS prior to the reported incident, and who were involved in the purchasing or ordering of the food, were asked to report on the causes.

Within the sample, half of the causes reported by adults (51%) and over half reported by parents (58%) were attributed (at least partially) to an error on the part of the staff. This includes:

-

FHS requirements not being passed on: 17% of adults and 10% of parents reported that they or their child provided their FHS requirement, but that the member of staff who prepared their meal was unaware of this.

-

Error in information provision: 13% of adults and 16% of parents said they or their child told a member of staff about their FHS, but were given the wrong information.

-

Allergen information not being checked: 12% of adults and 14% of parents reported that the person who gave them (or their child) the food did not check the allergen information.

-

Receiving the wrong meal: 15% of both adults and parents reported that they (or their child) received the wrong order or meal. Whilst being provided with the wrong meal or order is not specific to FHS customers, it has more significant consequences for them and is a food safety issue for them.

-

Incorrectly labelled food: 9% of adults and 15% of parents reported that incorrectly labelled food was, at least partially, the cause of their FHS incident. This could include an error in the ingredients list or allergens not being emphasised.

In addition to this, 7% of both adults and parents reported that although they had disclosed their FHS, the FBO didn’t understand their requirements.

Overall, these findings suggest that inaccurate information and communication issues on the part of FBOs and their staff may have played a role in some of the reported FHS incidents in this research. In addition, mistakes that may happen in general (i.e. wrong meals being served) may be occurring, which have more serious consequences for consumers with FHS requirements than those without.

Confirmation of FHS requirements

Some businesses confirm that FHS requirements have been met at the point of providing food to consumers. This can be done proactively (either verbally or through marking the food in some way), or reactively, where the consumer checks with a staff member when they receive their food.

In this sample many participants received confirmation that their FHS needs have been met when this was not the case (as they then go on to have a reaction or near miss). Of the consumers that reported disclosing their FHS requirements (n=288 adults and 124 parents), around 7 in 10 (72%) and parents (71%) reported that they received confirmation that their FHS needs had been met at the point of receiving their food.

Confirmation was most commonly given verbally (56% of adults and 59% of parents), with smaller proportions of participants reporting that food was labelled or marked (10% of adults and 4% of parents), or that FHS requirements were confirmed in another way (4% of both adults and parents). It was also more common for the consumer to actively ask staff to confirm this (39% of adults and 46% of parents), with it being less common for confirmation to be given proactively by FBO staff (18% of adults and 17% of parents).

When asked how those who reported a near miss avoided a reaction, over a third of adults (36%) and over half of parents (55%) said that they avoided a reaction as they checked with staff when their food arrived that their FHS had been taken into account.

These findings indicate that on receiving their food many consumers are looking for reassurance from the FBO that their food is safe for them. However, on occasions, they are being incorrectly told that their FHS requirements have been met, when this is not the case.

2.3.2. Consumer behaviour on occasions where there were FHS incidents to loose food

If consumers disclose that they have FHS requirements when ordering or purchasing food, this can be helpful in ensuring that businesses are informed and can take reasonable precautions when preparing food. This research has found that although the majority of participants did report disclosing their FHS requirements (82% of both adults and parents), 15% of both adults and parents reported that they (or their child) did not disclose their FHS requirements, even when asked.

Beyond disclosure of FHS requirements, there were also a number of reported causes that related to consumer behaviour, although these were reported less commonly than the above discussed staff errors. 12% of causes reported by adults and 17% of causes reported by parents related to consumer behaviour. This includes:

-

7% of both adults and parents reporting that they or their child did not check the allergen information

-

4% of adults and 10% of parents reporting misreading or misunderstanding the written information on the label/ menu of food sold loose.

-

2% of adults and 3% of parents reported ordering a vegan item thinking that it would be suitable for them or their child

Consumers misunderstanding information could be affected by FBOs providing allergen information which is difficult for consumers to understand. Of those consumers who were involved in ordering or purchasing the food (n=247 adults and 94 parents), 3 in 10 said that allergen information was difficult to understand (30% of adults and 27% of parents). Furthermore, although not necessarily linked to the comprehension of consumers, around half (51%) of adults and over half (56%) of parents said they asked for clarification on some allergen information.

2.3.3. Packaged food

Although the primary focus of this research was on FHS incidents involving loose food, there are also a number of findings related to packaged food (n=205 adults and 216 parents) that may help build the understanding of consumers with FHS’ experiences.

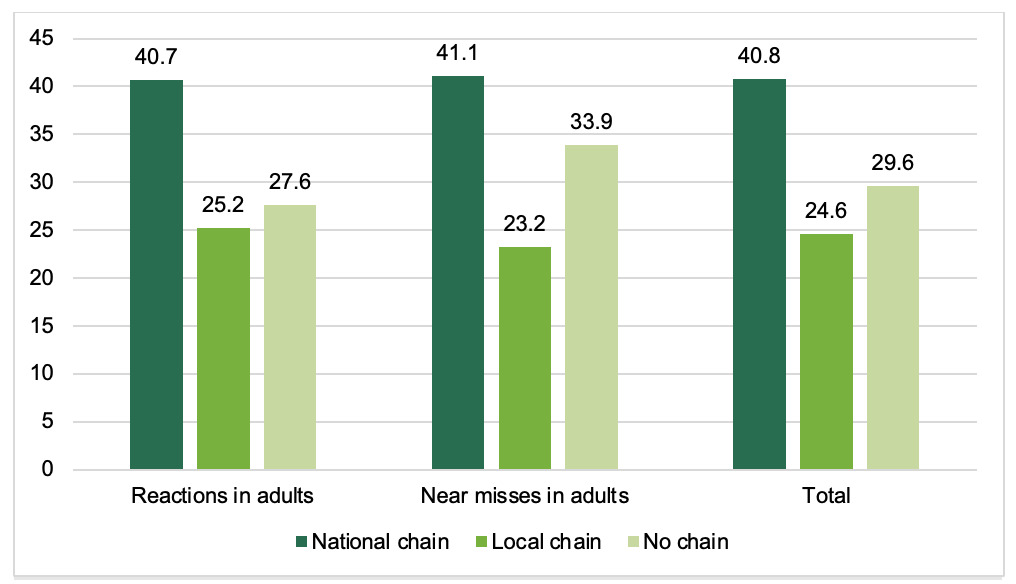

Packaged food was most commonly purchased from a supermarket (28% of adults and 33% of parents), however there were also relatively large groups who reported purchasing from a restaurant (17% of adults and 27% of parents) or takeaway (18% of adults and 11% of parents). Incidents more commonly involved prepacked food (56% of adults and 66% of parents) than PPDS food (36% of adults and 29% of parents).

2.3.4. Conclusions

This section summarises the key points made in the above discussion.

-

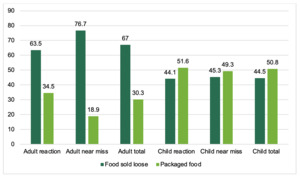

For adults, the majority of the reported FHS incidents were to loose food (67%), compared to packaged food (30%). For parents, FHS incidents were relatively equally split between loose food (45%) and packaged food (50%). As could be expected, loose food was most commonly purchased in restaurants, and packaged food was most commonly purchased in supermarkets.

-

Most consumers (82% of adults and parents) reported that they disclosed their FHS requirements when they purchased or ordered food, however, a minority (15% of adults and parents) did not.

-

The majority of adults (75%) and parents (83%) reported that allergen information (in some form) was provided in the reported incidents, and only a very small proportion of people (3% of adults and 0% of parents) reported asking for allergen information and that it was not provided by the business.

-

However, there were some reported issues related to the information available. Some consumers reported issues with the accuracy of allergen information,[3] and some found the information difficult to understand.

-

Many consumers reporting incidents to loose food felt that errors were made by the FBO and staff, and there are indications that these took place throughout the consumer ‘journey’. These include errors in communication (within the FBO), inaccurate information and consumers being provided with the wrong meal or order.

-

Furthermore, high rates of the sampled adults (72%) and parents (71%) reported that businesses confirmed that their FHS requirements had been met, when, given that they ultimately reported either a near miss or a reaction, they should not have been.

2.4. Key Findings

Participants were required to have experienced a FHS incident (including both reactions and near misses) in the last five years. Participants were then asked to consider their most recent FHS incident when answering questions. The findings below therefore relate to these most recent incidents.

The following findings focus on the experiences of consumers who purchased loose food, as this was the primary focus of this research. Some data was also collected on consumers who reported that their most recent incident was to prepacked food (including PPDS and packaged foods).

When interpreting findings on loose food it should be noted that responses are skewed to incidents which occurred in restaurants (this was the plurality of responses from respondents- 40% of adults and 43% of parents), and to a lesser extent cafés (16% of adults and 15% of parents) and will therefore likely reflect the consumer ‘journey’ when purchasing food at these types of places.

2.4.1. Research Objective One: Characteristics of reactions and near misses

As discussed above, participants reported on incidents that have occurred in the last five years, and only answered questions on their most recent incident. This means that these findings cannot be taken as representative of all reactions and near misses.

Rates of FHS incidents

-

Around six in ten adults (63%) and parents (61%), who have had an incident in the last 5 years, reported that they or their child had experienced between 1 and 5 reactions in the last five years. The frequency of reported near misses was very similar, with 63% of both adults and parents reporting between 1 and 5 near misses in the last 5 years. The majority of both adults (81%) and parents (87%) were reporting on an incident that had taken place in the last year.

-

Adults were more likely to report that their most recent incident was to food sold loose (67%) compared to food purchased in packaging (30%). For parents, this was more evenly split, with 45% reporting that their most recent incident was to food sold loose, and 50% reporting that it was to packaged food. Within packaged food (n=205 adults and 216 parents), this was more likely to have been prepacked food (56% of adults and 66% of parents) than PPDS food (36% of adults and 29% of parents).

Place and method of purchase for food sold loose

-

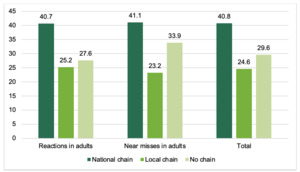

As discussed above, incidents involving food sold loose were most commonly involving food or drink purchased from a restaurant (40% of adults and 43% of parents). This was followed by a café (16% of adults and 15% of parents) and then a takeaway for adults (13%) or a canteen for parents (7%).

-

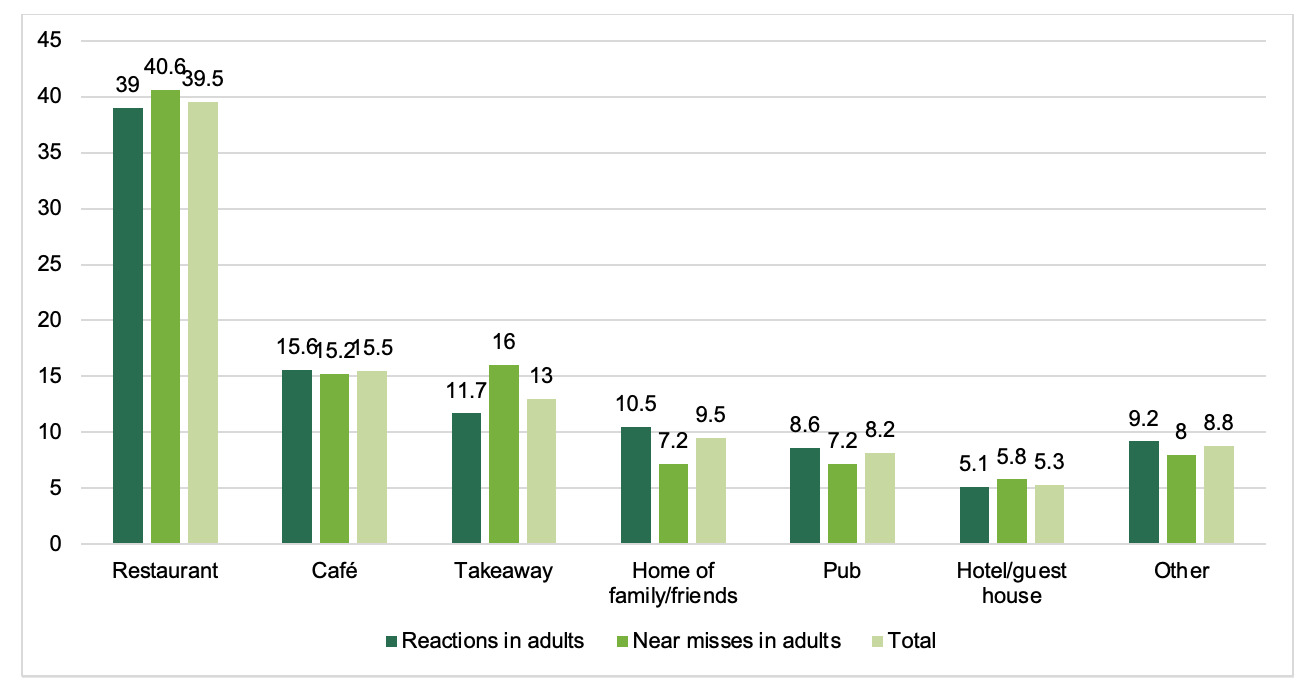

Just over half of adults (54%) and 7 in 10 parents (69%) reported that the loose food or drink in question was purchased from an establishment that was part of a chain. This finding likely reflects the frequency of where people eat and doesn’t necessarily reflect the impact of chains on FHS incidents.

-

Most commonly, the food or drink involved in the incident was a meal or prepared drink (74% of adults and 67% of parents). A further 21% of adults and 28% of parents indicated that the food was selected from a buffet, deli or market stall. This was evenly split between consumers serving themselves (10% of adults and 14%of parents) and a member of staff (11% of adults and 13% of parents).

-

When purchasing food or drink, it was most common for consumers to order via a member of staff (74% of adults and 68% of parents). This is likely impacted by the finding that the majority of food was purchased from restaurants, where it is more common to order food in this manner.

2.4.2. Research Objective Two: Understanding the consumer ‘journey’

Consumer disclosure of their FHS requirements (for food sold loose)

These findings relate only to adults and children who knew that they had FHS prior to the reported incident.

-

Self-reported disclosure of FHS by consumers was high: the majority of adults and parents (both 82%) reported that they disclosed their or their child’s dietary or allergy requirements when purchasing or ordering the food or drink, either proactively or in response to being asked.

-

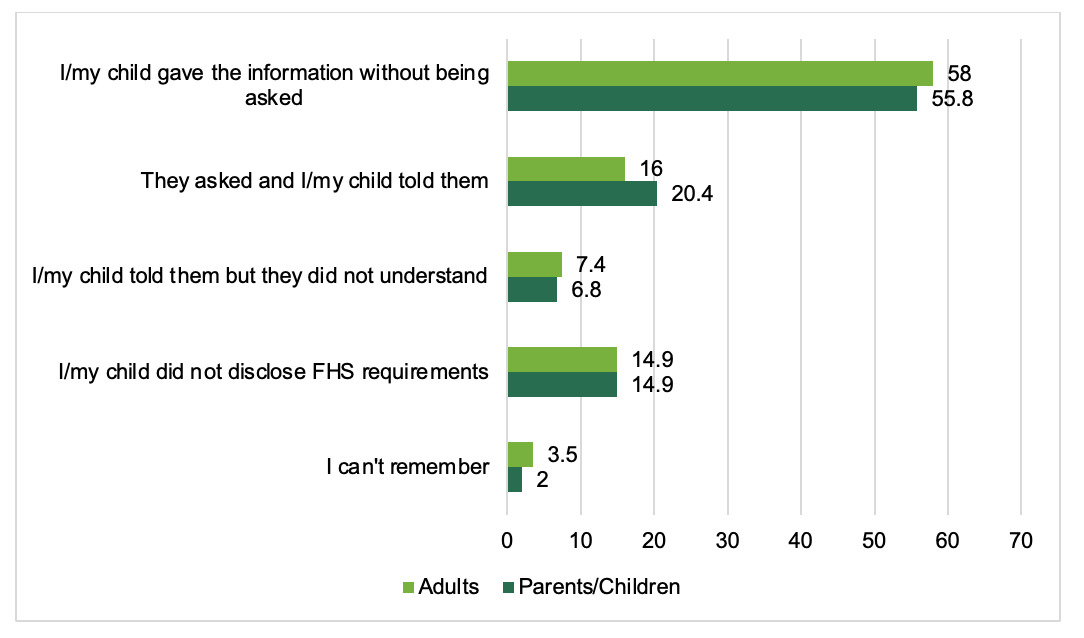

Over half of respondents indicated that they disclosed their FHS information without being asked (58% of adults and 56% of parents), whereas around a fifth disclosed in response to being asked (16% of adults and 20% of parents). For those who disclosed proactively it is not known whether they were prompted to disclose via a sign asking them to or how many of these FBOs would have asked about FHS if the consumer hadn’t already disclosed this.

-

7% of both adults and parents reported that although they had disclosed their FHS, the FBO didn’t understand their requirements.[4]

-

15% of both adults and parents reported that they (or their child) did not disclose their FHS. Most commonly, these consumers were not asked by the FBO (14% of adults and 12% of parents), however, 1% of adults and 3% of parents reported being asked and not providing their FHS information.

Provision of information (for food sold loose)

These findings relate only to adults and parents of children who knew that they had FHS prior to the reported incident, and who were involved in the purchasing or ordering of the food.

FBOs are required to make allergen information on the 14 regulated allergens available to consumers.[5] This can either be verbally or in writing and they do not have to provide it proactively. The findings below relate to consumers’ awareness and perception of the information that was available to them at the time of purchase. This relies on accurate recall, and in some situations, it is possible that allergen information would only be provided on request, which means that if consumers didn’t ask the FBO for this information, they wouldn’t receive this. Findings should be interpreted in light of this.

-

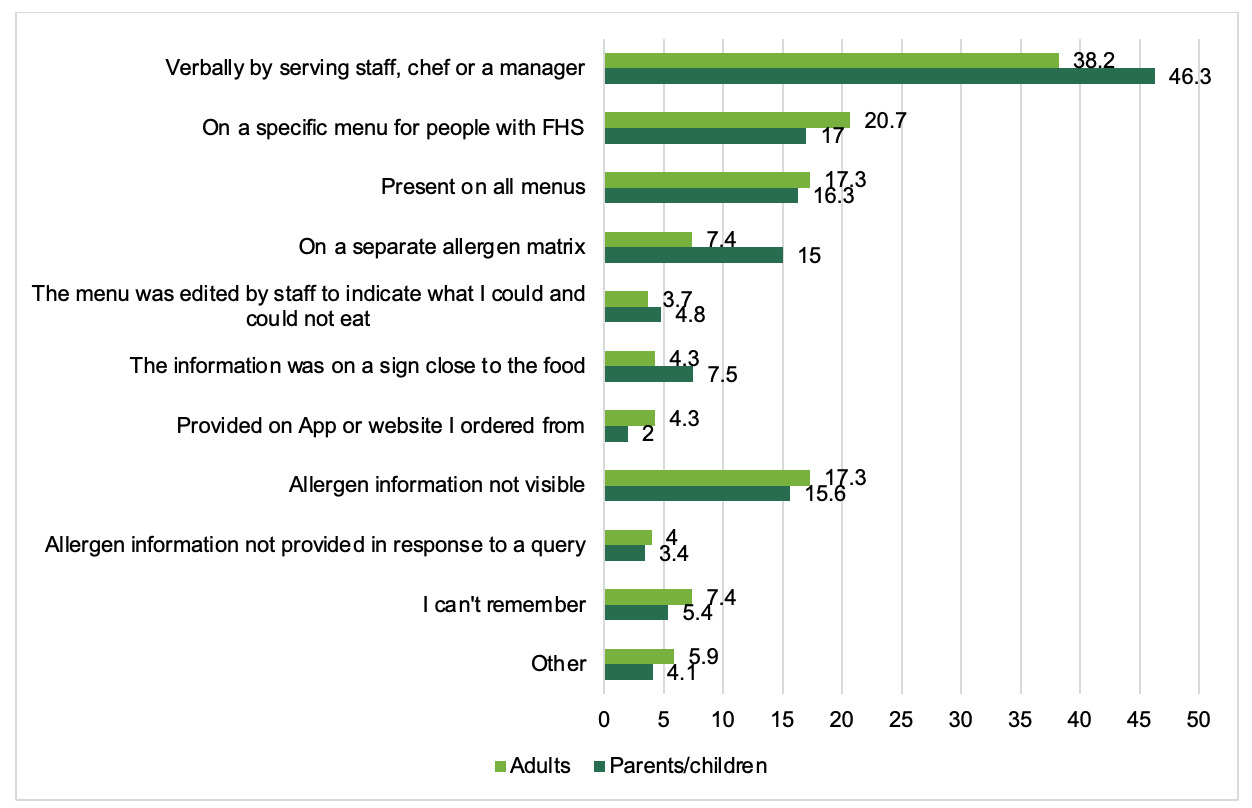

In the majority of the incidents consumers reported that allergen information was provided, either in written and/or verbal format (75% of adults and 83% of parents):

-

Verbal information was provided to 4 in 10 (38%) adults and nearly half (46%) of parents.

-

Written information was provided to half of adults (49%) and parents (53.1%).

-

-

Consumers reported a number of different ways that written allergen information was provided. These findings indicate the information that consumers reported as available. It is possible that this information was available to consumers, but they didn’t notice this information:

-

Most commonly, they reported being provided with a specific menu for people with FHS (21% of adults, 17% of parents).

-

The second most common format was that this was present on all menus (17% of adults, 16 of parents).

-

Less than 1 in 10 adults and parents reported being provided with a separate allergen matrix (7% of adults, 15% of parents).

-

Around 1 in 20 indicated that the menu was edited by staff to indicate what was suitable (4% of adults, 5% of parents).

-

Around 1 in 10 parents (8%) and 1 in 20 adults (4%) reported that allergen information was provided on a sign close to the food (this may be a reflection of the skewed sample, where 40% were reporting on restaurants).

-

Fewer than 1 in 20 participants reported that allergen information was provided on the app or website they ordered from (4% of adults, 2% of parents).

-

-

17% of adults and 16% of parents reported that allergen information was not visible when they purchased their food. As highlighted above, it is possible that this information was available to consumers, but they didn’t notice this information.

-

4% of adults and 4% of parents reported that allergen information was not provided in response to a query.

-

Of those who said allergen information was visible and were involved in ordering or purchasing the food or drink (n=247 adults and 94 parents), information on the specific allergens asked about was most commonly provided to respondents[6] (43% of adults and 35% of parents), followed by information on each of the 14 major allergens (15% of adults and 32% of parents) and information on all ingredients (13% of adults and 25% of parents).

-

Of those who said allergen information was visible and were involved in ordering or purchasing the food or drink (n= 247 adults; 94 parents), not all found it easy to understand, with 30% of adults and 27% of parents reported that it was difficult or very difficult to understand.

-

Although not necessarily linked to ease of comprehension, around half (51%) of adults and over half (56%) of parents said they asked for clarification on some allergen information.

-

Of those who reported disclosing their FHS requirements (n=307 adults and 122 parents), around two-thirds of both adults (72%) and parents (71%) reported that they received confirmation that their FHS needs had been met at the point of receiving their food. However, 34% of adults and 28% of parents indicated that their FHS requirements were not confirmed by the business. As all consumers surveyed for this research ultimately reported a reaction of near miss, this means that confirmation was given in error by the businesses.

-

Confirmation was most commonly given verbally (57% of adults and 63% of parents). It was more common for the consumer to actively ask staff to verbally confirm (39% of adults and 46% of parents), than for verbal confirmation to be given proactively (18% of adults and 17% of parents).

-

1 in 10 (10%) adults and less than 1 in 20 (4%) parents reported food being labelled or marked in some way to confirm requirements. 4% of both adults and parents reported that FHS requirements were confirmed in another way.

2.4.3. Research Objective Three: Reported causes of incidents to packaged and loose food

Reported causes of incidents involving food sold loose

These findings relate only to incidents involving food sold loose, and to adults and parents of children who knew that they had FHS prior to the reported incident.

Participants were asked to report what they felt had caused their FHS incident. It was not possible in this research to verify the accuracy of these proportions. When asked to report on the causes of their incidents, participants were able to select multiple causes.

-

The most common reported cause was cross-contamination; this was reported by a quarter of both adults (25%) and parents (27%). It is not possible to know the underlying cause of this reported cross-contamination or whether this relates to a business error.

-

Half of adults (51%) and over half (58%) of parents indicated an FBO error as causing the incident:

-

17% of adults and 10% of parents reported that they provided their FHS requirement, but that the member of staff who prepared their meal was unaware of this;

-

15% of adults and 9% of parent received the wrong order or were provided with the wrong meal;

-

13% of adults and 16% of parents told a member of staff about their FHS, but were given the wrong information;

-

12% of adults and 14% of parents reported that the person who gave them (or their child) the food did not check the allergen information; and,

-

9% of adults and 15% of parents reported that food was incorrectly labelled. This was the second most common cause reported by parents.

-

-

15% of both adults and parents reported that there was no ingredients list provided. It is not a requirement for FBOs to provide consumers with this information, and so should not be considered a business error. This was the second most common cause reported by adults.

-

In relation to provision of information, only 1% of adults and no parents reported asking for allergen information, but that this was not provided by the FBO.

-

12% of adults and 17% of parents reported causes that related to consumer behaviour:

-

7% of adults and 7% of parents reported not checking the allergen information

-

4% of adults and 10% of parents reported misreading or misunderstanding the written information on the label

-

2% of adults and 3% of parents reported ordering a vegan item thinking that it would be suitable for them

-

-

Furthermore, participants who reported a near miss (n=138 adults and 67 parents) were asked how they avoided having a reaction. Most commonly, this was due to the allergen being seen in the food (40% of adults and 94% of parents). Other common factors reported to prevent a reaction were:

-

That they checked with waiting staff when the food arrived (36% of adults and 55% of parents);

-

That they thought they tasted the allergen and so stopped eating (33% of adults and 59% of parents), and;

-

That they realised they had been given the wrong order (18% of adults and 37% of parents).

-

Incidents involving packaged food

The findings in this section relate to incidents involving packaged food (either prepacked or PPDS).

-

Of the participants who reported that their incident involved packaged food (n=205 adults and 216 parents), this was more likely to have been prepacked food (56% of adults and 66% of parents) than PPDS (36% of adults and 29% of parents).

-

Packaged food involved in FHS incidents was most commonly purchased from a supermarket (28% of adults and 33% of parents), followed by a restaurant (17% of adults and 27% of parents) or takeaway (18% of adults and 11% of parents). This likely reflects the most common places where packaged food is sold to consumers.

Outcomes of FHS incidents

These findings relate to all FHS incidents captured in the survey (food sold loose as well as packaged food).

-

42% of the sampled adults and 28% of parents did not treat the reaction with anything. Where treatment was given, 55% of adults and 65% of children took antihistamines, 21% of adults and 27% of children were treated with self-administered adrenaline, and 17% of adults and 35% of children were administered adrenaline by a healthcare provider.

-

It was more common for parents (63%) to make a complaint about the incident than for adults (53%).

-

Out of the respondents who reported making complaints (n=356 adults and 266 parents), the most common course of action was to complain to the food provider (78% of adults and 68% of parents).

-

Respondents also reported complaining to a number of other points of contact:

-

14% of adults and 25% of parent reported to the Food Standards Agency

-

8% of adults and 20% of parents reported to the local authority

-

10% of adults and 25% of parents reported to the environmental health officer at the local council

-

15% of adults and 35% of parents reported to a doctor or other healthcare professional

-

3. Introduction

This report presents findings from research conducted by Aston University on behalf of the Food Standards Agency (FSA). The FSA is the independent government department responsible for protecting public health and consumers’ interests in relation to food across England, Wales and Northern Ireland. The FSA is responsible for allergen labelling, and for providing guidance to consumers with food allergies, food intolerances or coeliac disease (referred to collectively as food hypersensitivities (FHS)). This includes working with consumers and the food industry to ensure consumers with food hypersensitivities can make safe and informed choices. FHS includes food allergy, food intolerance and coeliac disease. Eating a food which you are sensitive to, can result in an adverse reaction with unpleasant and sometimes life-threatening symptoms. Management of FHS therefore involves individuals being aware of risks and determining if a food is safe to eat.

3.1. Aims of the project

The objective of this research was to understand the circumstances that could lead to reactions and near misses to food or drink in people with food hypersensitivities. This research explores the reactions and near misses that have taken place in the last five years in adults and children with either self or medically diagnosed FHS, in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Findings will add to the evidence base in this area and inform the FSA’s food hypersensitivity programme.

Specific research aims were to:

-

Characterise reactions and near misses. For example, the type of business the food was purchased from and what type of food, loose or packaged, was involved.

-

Understand the ‘journey’ which resulted in a reaction or near miss. For example, how the food was purchased and the provision of allergen information.

-

Identify the self-reported cause(s) of reactions and near misses to loose food.

Results from this research will feed into the evidence base to inform the FSA’s food hypersensitivity programme.

3.2. Definitions

The following definitions are used throughout this research:

-

Food Hypersensitivity (FHS): Collective term for food allergy, food intolerance and coeliac disease, defined as experiencing a physical reaction after consuming certain foods.

-

Reaction: Experiencing physical symptoms due to eating or drinking something, due to a food hypersensitivity

-

Near miss: Buying, ordering or receiving food or drink that the consumer believed did not contain any ingredients they had a hypersensitivity to. However, the food or drink received did contain the ingredient/s and the consumer: a) noticed this before eating the food or drink; or b) ate the food or drink and did not have a reaction (physical symptoms due to their allergy, intolerance or coeliac disease).

-

Incident: A collective term for reactions and near misses.

-

Packaged food: Food already in packaging when selected/ordered. This includes prepacked (placed in packaging by another business such as crisps and ready meals) and prepacked for direct sale food (PPDS) (placed in packaging by the same businesses on the same site such as grab and go sandwiches).

-

Loose food: Food that is not in packaging when selected/ordered such as meals in a café/restaurant or loose cheese on a deli counter.

4. Methodology

This section summarises the research approach. More detailed information on sampling, development of the survey and the methodology can be found in the technical report.

4.1. Study design

Two online surveys were used, one for parents of children (0-17 years) with FHS and one for adults with FHS who had experienced a near miss or reaction to food (loose or packaged) in the last five years. Adults reported on the last time they had experienced either a reaction or a near miss (whichever was their last experience) and parents reported on this for their child.

Participants were living in England, Wales or Northern Ireland. Those living in Scotland were excluded as the FSA does not have responsibility for food allergen labelling in Scotland (this is under the remit of Food Standards Scotland). Survey data was collected between 27th February and 28th March 2023.

The survey was developed through discussion with the study team and the FSA and was cognitively tested with 14 people with FHS.

4.2. Participant recruitment and characteristics

An opportunity sample (anyone who saw the study advert and was eligible to take part) was recruited through advertising to people on an online survey panel (hosted by Qualtrics) and via allergy organisations: Allergy UK, the Anaphylaxis Campaign, the Natasha Allergy Research Foundation and Coeliac UK. The survey was also advertised on social media by the FSA, the study team and by Birmingham City Council. Adverts were emailed to Aston University students and staff (at the university of the lead author). Snowball sampling involved the participants being asked to recruit further participants through their contacts, network groups and acquaintances. Targets set prior to data collection were to collect 100 adults and 100 parents in each of the categories of food allergy, food intolerance and coeliac disease.

A total of 676 adults and 425 parents of children with FHS completed the survey. The number of participants reporting each type of FHS are shown in Table 1. A total of 25% (171) of adults reported multiple FHS and 33% (138) of parents reported their child had multiple FHS.

The majority of adult respondents identified as female (74%), White British (82%) and lived in England (90%), and 52% were aged between 25 and 44 years. A total of 57% were educated to university level and just over half (54%) were working full-time. The sample characteristics for parents were very similar to adults. Most parent respondents identified as female (68%), the mother of the child they were reporting for (69%), were White British (83%) and lived in England (82%). The majority were in the 25-44 year age bracket (75%), were educated to university level (72%) and were working full-time (65%). Demographic characteristics can be found in Table 2 and in Table A2.

For children with FHS, 57% were male and 43% were female. Ages of children ranged from 0 to 17 with a mean of 8 years: 40% were in the 0-6 year age group, 26% in the 7-11 and 24% in the 12-17 year age group.

The majority of adults and parents reported that their, or their child’s, FHS had been diagnosed by an NHS or private medical practitioner, such as a G.P., dietician, or allergy specialist in a hospital or clinic. For adults, 91% of reports of food allergy (250 out of 274), 74% of reports for food intolerance (230 out of 311) and 99% of reports of coeliac disease (305 out of 308) were medically diagnosed. For parents, 99% of reports of food allergy in their child (255 out of 258), 99% of food intolerance (187 out of 194) and 97% of reports of coeliac disease (182 out of 188) had been medically diagnosed.

When asked to rate how severe their FHS was in general, almost half (48%) of adults rated their FHS as moderate, with fewer reporting it as severe (36%) or mild (15%). Parents rating of their child’s FHS were roughly equally divided between moderate (45%), or severe (40%) with fewer rating FHS as mild (14%). Ratings split by type of FHS are reported in Tables 3 and 4.

The survey asked participants to report on their latest incident- an incident was classed as a reaction or near miss. The majority of responses in the survey related to a reaction (rather than near miss); 73% of adults (N=496) and 65% of parents (n=277) stated the most recent incident was a reaction, 27% of adults (N=180) and 35% of parents (N=148) reported it was a near miss. The majority of responses related to an incident in the last year (adults 81% and parents 87%). Around 1 in 10 adults (8%) and parents (8%) reported on an incident 1-2 years ago and 9% of adults and 5% of parents more than 2 years ago.

Although parents were reporting for their child, most were present when the food or drink was ordered or purchased and so these parents were not relying on accounts from their child or another person. For food sold loose, 79%, (N=149 out of 189) said they were present and 61% (N=116 out of 189) said they ordered the food or drink themselves. Parents reported that 18% (N=33) of the time, the child ordered or purchased it and 19% (N=35) of the time someone else did (N=5, 3% could not remember or did not know). For packaged food, most parents (82%) said they were present when the food or drink was purchased. Most parents (72%) ordered or purchased the packaged food or drink themselves, 16% of parents reported that their child ordered or purchased it, and 12% said that someone else ordered or purchased it. Proportions were very similar for reactions and near misses. Almost all parents said they were with their child when they had a near miss (91%) or a reaction (90%).

4.3. Data analysis and reporting conventions

All data reported is for this sample and is not weighted. We are not able to determine whether this is a representative sample of those living with FHS in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, as it is not currently known what a representative sample is for people with FHS the UK.

As indicated in the definitions, the term ‘incident’ is used when referring to data that includes both those reporting a reaction and those reporting a near miss.

Descriptive information is provided for all survey questions in the form of text, tables and graphs where appropriate. Further information can be found in tables in the Appendices. All percentages in the text are rounded up or down to the nearest whole number, there may therefore be rounding errors where totals do not always result in 100%. Base numbers of those answering each question are reported under the tables and charts and include those stating ‘I don’t know’ or ‘I can’t remember’, unless stated otherwise. Base numbers for sections on food sold loose, packaged food and outcomes of reactions and near misses exclude participants who stated that they did not know what type of food packaging was involved. Responses that were not selected by any participant are not included in the figures in the main report but are included in tables in the Appendices.

Comparisons across groups were conducted using χ2 tests for categorical data. Results were taken as significant if p<0.05. All tests were two-tailed. Answers for the following groups were compared:

-

Reactions compared to near misses

-

Parent compared to adult

-

Age of adult participant (18-25 years compared to 26 years and over)

-

Age of child (6 years and under; 7-11 years and 12-17 years)

-

Severity of condition (mild, moderate or severe)

These groups were compared where there were sufficient sample sizes for answers: when the number of adults or parents responding to the question was 100 or more. Where analysis was undertaken because of differences seen in the descriptive statistics but numbers did not meet this criterion, it is noted that findings should be treated with caution. Sub-group analysis could not be conducted by UK country due to the low numbers of participants from Wales and Northern Ireland. It was not possible to explore whether food or drink was purchased differently in different types of food business, as sample sizes for places where food or drink was provided from was too low for any source other than restaurants. It was also not possible to explore whether there were measures in place for cross-contamination for those who served themselves or where a member of staff packaged loose food for them, or if there was a way or reporting dietary requirements online, as numbers reporting food being provided in these ways were too low. Nor was it possible to look at different places of purchase by age categories, as numbers were only large enough for restaurants.

5. Results

5.1. Overview of reactions and near misses

The majority of adults (63%) and parents (61%) reported they or their child had experienced 1-5 reactions in the last five years; 20% of adults and 19% of parents reported 6-10 reactions. For near misses, the frequency of reporting was very similar with the majority of adults (63%) and parents (63%) reporting 1-5 near misses and 19% of adults and 12% of parents reporting 6-10. Frequencies of reactions and near misses for adults can be seen in Figures 1 and 2.

The number of reactions or near misses was analysed to see if there were associations with age. There was no significant association between number of reactions or near misses and age of adult. For children, there was no significant association between the number of reactions and age group, however, there was an association between the number of near misses and age, with older children experiencing more near misses than younger children. For 12-17 year olds, 23% were reported to have 6-10 near misses compared to just 11% of 0-6 year olds and 9% of the 7-11 year olds (χ2(2)=7.96, p=0.02).

5.2. Reactions and near misses to food sold loose

Adults were more likely to say that the food involved in their most recent incident was sold loose (i.e. not packaged before they bought it) (67%, N=453) than it was packaged (30%, N=205). Loose food was more likely to be reported by adults who had a near miss (77%) than reported by those who had a reaction (64%) (χ2(1)=10.35, p<0.001).

In contrast, parents were more evenly split with 45% (N=189) saying that the last reaction or near miss involved loose food and 50% (N=216) saying it involved packaged food. Significantly fewer parents (45%) than adults (67%) reported that the last incident was to food sold loose (χ2(1)=54.54, p<0.001). Figure 3 shows the type of food involved in the latest reaction or near miss reported by parents and adults.

5.2.1. Place and methods of purchase for food sold loose

For food sold loose, the most common place of purchase of food or drink causing an incident was a restaurant; this was the case for both adults (40%) and parents (43%). This was followed by a café (16% for adults; 15% for parents) and then a takeaway for adults (13%) or a canteen for parents (7%). Other places such as a pub, supermarket, plane/train, independent shop, residential establishment, catered event or home of family or friends were each reported by 10% of participants or less (see tables A3 and A4). Figures 4 and 5 show the most commonly cited places food was provided from for adults and parents.

Incidents were often related to food/drink purchased at a chain. Just over half (54%) of adults and 7 in 10 (69%) parents reported that the loose food or drink in question was purchased from an establishment that was part of a chain. Both adults (32%) and parents (46%) were more likely to report that it was a national chain that was involved rather than a local chain (adults, 22%, parents 23%); 41% of adults and 27% of parents reported that it was not from a chain. This data cannot be used to conclude that FHS incidents are more likely to occur in establishments that are part of a chain, compared to non-chain establishments, or in national chains as opposed to local chains. Findings are likely to reflect the frequency of where people eat.

For restaurants, which were the most common place of purchase for incidents involving loose food (reported by N=179 adults and N=82 parents), 65% of adults reported that the incident occurred in a restaurant was part of a national or local chain, and 30% said it was not part of a chain. As follows the pattern of results when all food establishments were examined together, more national chains were reported for these incidents (41%) than local chains (25%). Proportions for reactions and near misses can be seen in Figure 6. Results are not broken down for parents as number of parents in this sample is too small.

Food or drink was most commonly provided in the form of a meal or prepared drink (adults 74% and parents 67%). However, a fifth (21%) of adults and nearly 3 in 10 (28%) parents indicated that the food was selected from a buffet, deli, market stall etc (either by themselves or by a member of staff selecting it for them). This was roughly evenly split between them serving themselves (adults,10%; parents,14%) and a member of staff serving them (adults, 11%, parents, 13%).

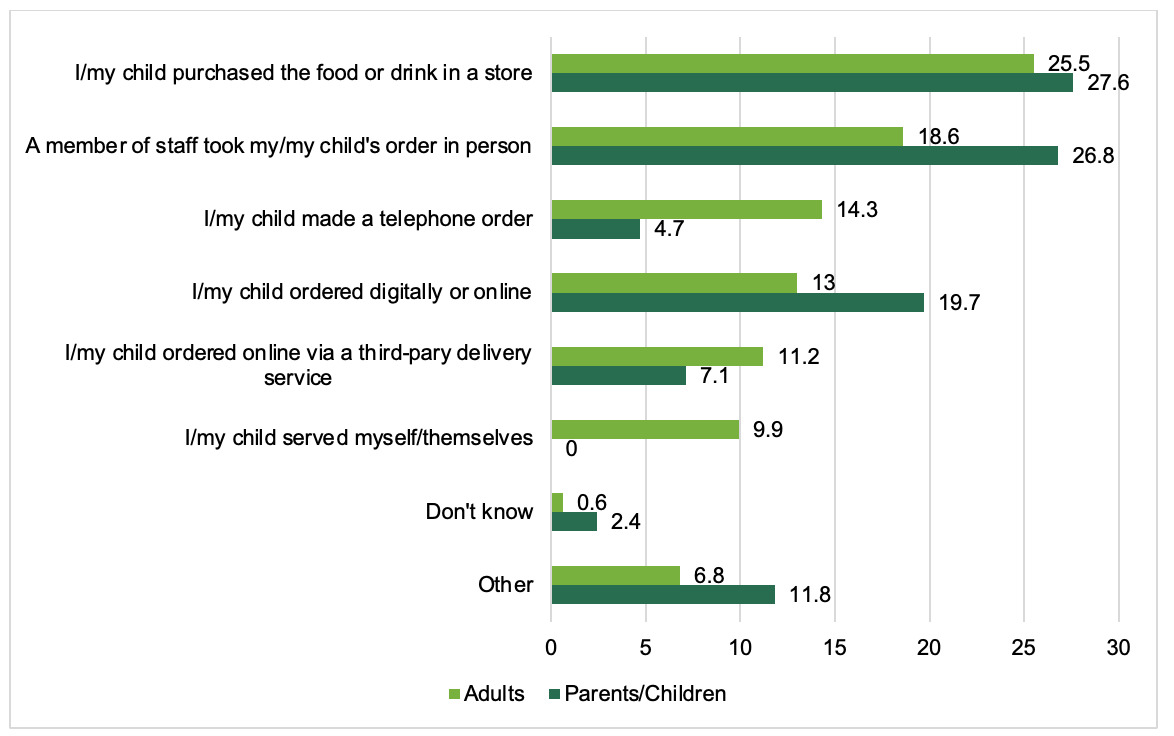

Most commonly, participants ordered via a member of staff (74% of adults and 68% of parents). This reflects that loose food or drink tended to be purchased from restaurants. Each of the other ways in which food was purchased or ordered such as online or via telephone, was reported by 7% of people or less. Please see tables A5 and A6 in the annex for further detail on this.

The majority of people said that the reaction or near miss occurred at the place the food or drink was purchased from. This was the case for 79% of adults and 82% of parents reporting on their/ their child’s near miss and 77% of adults and 82% of parents reporting on their/ their child’s reaction. This is likely to be influenced by the fact that most loose food FHS incidents involved food purchased from a restaurant, where it is commonplace to eat on the premises.

5.2.2. Communicating allergen or dietary information

The results in this section report only on those who knew that they, or their child, had a FHS before the incident they are reporting on.[7]

To provide a safe environment for customers with FHS, food business operators (FBOs) should be aware of a consumers’ FHS, so that they can behave accordingly in the preparation and serving of food, and consumers with FHS should be provided with the information they need to make an informed decision on what food and drink they order.

Self-reported disclosure of FHS by consumers was high: the majority of adults and parents (both 82%) said they disclosed their/ their child’s dietary or allergy requirements when purchasing or ordering the food or drink, either proactively or in response to being asked. However, 15% of both adults and parents reported that they didn’t disclose. This was more commonly that they weren’t asked (14% of adults, 12% parents), however a very small minority said that they were asked and didn’t provide the information (1% adults and 3% of parents). 7% of both adults and parents also reported that although they disclosed their requirements, the business did not understand (see Figure 7).

It was more common for people to report disclosing proactively (adults 58% and parents 56%) than in response to being asked (16% of adults and 20% of parents). There are indications that some groups are more or less likely to pro-actively disclose than others: those with (self-reported) severe FHS were more likely to proactively disclose than those with self-reported moderate/ mild FHS (89% v 63%),[8] whilst younger adults (below 26 years) were less likely to proactively disclose their FHS than older adults (26+ years) (67% v 80%).[9] It is not known whether people who disclosed proactively were prompted to do so by a sign asking them to. If people had not disclosed proactively, they may have been asked and so the number of food businesses not asking first needs to be interpreted with this in mind.

Food business operators (FBOs) must communicate the presence of allergens in food to consumers. The Regulation on the Provision of Food Information to Consumers (FIC) requires businesses to ensure that all mandatory food allergen information (relating to the 14 regulated allergens) is accurate, available, and easily accessible to customers. For food sold loose in the out of home sector (for example, in restaurants) this mandatory allergen information can be provided verbally or in writing. It should be noted that the findings provided below on written information refer to participant’s awareness and are not objective measures of presence of written information. For example, allergens matrices and specific menus may only be provided when asked for and therefore may be present, but not reported by participants if they did not ask for them.

On average adults selected 1.3 and parents selected 1.4 ways in which allergen information was provided when they ordered or purchased the food or drink involved in the incident. Allergen information was reportedly provided, either verbally and/or written, to 75% of adults and 83% of parents. Nearly 4 in 10 (38%) adults and nearly half (46%) of parents said that allergen information was provided verbally by the FBO. For 49% of adults and 53% of parents there was some form of written information. However, 17% adults and 16% parents said allergen information was not visible. This does not mean that it wasn’t present, it means that people reported that they did not see it.

A fifth of adults (21%) and 17% of parents said that allergen information was provided to them on a specific menu and 17% of adults and 16% of parents said that it was present on all menus. These were the most common sources of written information reportedly used, along with an allergen matrix for parents (15% of parents reported this, 7% of adults). As noted earlier these percentages will be skewed by the high percentage (and the plurality) of participants reporting on restaurants. Figure 8 provides information on the ways in which allergen information was provided for food sold loose. Participants could select as many answers as they wished.

For restaurants, the pattern was similar to that seen for all premises types. Allergen information was reportedly provided, either verbally and/or written, to 84% of adults and 91% of parents. 4 in 10 (41%) adults and over 5 in 10 (55%) parents said that allergen information was provided verbally by the FBO. 61% of adults and 57% of parents said there was some form of written information. However, 10% adults and 7% parents said allergen information was not visible. A fifth of adults (26%) and 12% of parents said information was provided on a specific menu for people with FHS; 15% of adults and 16% of parents said that it was present on all menus These were the most common sources of written information reported used, along with a separate allergen matrix (15% for adults, 13% for parents).

Of the participants who were involved in ordering or purchasing the food or drink who said allergen information was visible (247 adults and 94 parents), the majority (adults 43%, parents 35%) reported receiving information about specific allergens they had asked about when (Figure 9). Regarding the 14 regulated allergens, 32% of parents recalled that information was available on the presence of the 14 major allergens in the food or drink, but only 15% of adults reported this information as present. Around 1 in 7 parents (15%) and adults (14%) reported that information on some of the 14 major allergens was provided. A quarter of parents (25%) stated that information on all ingredients in the food or drink was present, compared to 12% of adults. ‘May contain’ labelling was reported as present by 17% of parents and 12% of adults.

Of those who reported they purchased the food at a restaurant, most stated they received information about specific allergens they had asked about when ordering or purchasing the food or drink (adults 28%, parents 18%). Regarding the 14 regulated allergens, 17% of parents and 13% of adults recalled that information was available on the presence of the 14 major allergens in the food or drink. Only 4% of parents and 9% of adults reported that information on some of the 14 major allergens was provided. Similar numbers of parents (12%) and adults (10%) stated that information on all ingredients in the food or drink was present. ‘May contain’ labelling was reported as present by only 5% of parents and 7% of adults.

Of those who were involved in ordering or purchasing the food or drink, who said allergen information was visible, not everyone found it easy to understand: 30% of adults and 27% parents said they found it difficult or very difficult. However, more people said it was easy than difficult to understand (44% of adults and 38% of parents said it was easy or very easy) (Figure 10). There were no significant differences in ratings of ease between adults and parents or between people reporting on reactions and near misses. Around half (51%) of adults (n=189 out of 368) and over half (56%) of parents (n=79 out of 140) who had ordered or purchased the food or drink themselves said they asked for clarification on some allergen information.

Businesses can signal to the customer that FHS requirements have been met, at the point that the customer receives their food. This can be done, for example, through offering verbal confirmation or using a visual indication (e.g. a flag on the food). Confirmation at this point can prevent reactions by identifying any communication errors regarding the FHS before it’s too late. Of the adults and parents that disclosed their FHS, around two thirds said that when they received their food/drink there was confirmation that FHS requirements had been met (64%, N=184 for adults; 67%, N=83 for parents). However, a third (34%) of adults and nearly 3 in 10 (28%) parents said that they didn’t receive confirmation. Significantly more adults reporting a near miss (44%, N=50 out of 114) did not receive any confirmation compared to those reporting a reaction (27%, N=47 out of 174), (χ2(1)=13.25, p<0.001). Numbers were too small to run this comparison for parents.

Confirmation was most commonly given verbally (57% for adults, 63% for parents) as opposed to their food/drink being labelled or marked in some way (10% for adults, 4% for parents). Verbal confirmation was more likely to have been given in response to the person asking staff (39% of adults; 46% of parents) rather than it being given proactively by staff either verbally or by food being marked (29% of adults; 21% of parents) (Figure 11).

5.2.3. Causes of reactions or near misses to food sold loose

Participants were asked what caused their near miss or reaction to food sold loose. Participants could select multiple reasons; on average each adult and parent selected 1.4 reasons. As this research relies on self-reported consumer perceptions, the reasons given cannot be verified. Figure 12 presents the causes reported by adults for their reactions and near misses. Figure 13 presents the causes reported by parents for their child’s reaction or near miss.

Cross-contamination

A quarter of both adults (25%) and parents (27%), reported cross-contamination as the cause of their FHS incident. This was the most common reported cause for both groups. Significantly more participants reporting a reaction (31% for adults, 40% for parents) compared to a near miss (15% for adults, 12% for parents) thought that it was due to cross-contamination (see Annex B for statistical test results). Due to the nature of this research, it is not possible to verify this cross-contamination, and it is possible that this was perceived cross-contamination by the consumer.

Business Behaviour

Many participants selected causes of their loose food FHS incident that can be broadly considered as relating to the behaviour of staff and management within a food business.

Half (51%) of adults and over half (58%) of parents attributed the cause of their incident (at least partially) to an error on the part of the food business.[10] This includes the 17% of adults and 10% of parents who reported that they provided their FHS requirement, but that the member of staff who prepared their meal wasn’t aware of this. This was the second most common cause of FHS incidents in adults. Significantly more adults reporting a near miss rather than a reaction reported this as a cause (23% of near misses compared to 14% of reactions).

This also includes the 15% of adults (11% of reactions and 21% of near misses) and 9% of parents (12% of reactions and 19% of near misses) who reported receiving the wrong order or being provided with the wrong meal. Significantly more adults reported that their near miss was caused by this reason than reactions (21% of near misses compared to 11% of reactions).

Also grouped under business error, 13% of adults (14% of reactions and 10% of near misses) and 16% of parents (15% of reactions and 16% of near misses) told a member of staff about their FHS, but were given incorrect information. Furthermore, 12% of adults (9% of reactions and 17% of near misses) and 14% of parents (14% of reactions and 12% of near misses) reported that the person who gave them (or their child) the food did not check the allergen information. Significantly more adults reported that their near miss was caused by this reason than reactions (17% of near misses compared to 9% of reactions).

The final error included in the above relates to labelling. 9% of adults (10% of reactions and 8% of near misses) and 15% of parents (16% of reactions and 13% of near misses) reported that food was incorrectly labelled. This could include an error in the ingredients list or that allergens were not emphasised. This was the second most common cause reported by parents.

Whilst not a business error (and so not included in the above net), as businesses do not need to provide this information, 15% of adults attributed their FHS incident to there being no ingredients list (16% of reactions and 14% of near misses). This was the third most common cause for adults. For parents, a lack of an ingredients list was jointly the second most common cause, with 16% reporting this (9% of reactions and 24% of near misses). Significantly more parents reporting a near miss compared to a reaction thought it was due to a lack of ingredients list (24% compared to 9%).

Consumer Behaviour

Less commonly, around 1 in 10 (12%) adults and nearly 1 in 5 (17%) parents selected causes that can be considered errors related to their own behaviour.[11] 7% of adults (8% of reactions and 4% of near misses) and 7% of parents (7% of reactions and 8% of near misses) reported not checking the allergen information. Furthermore, 4% of adults (4% of reactions and 6% of near misses) and 10% of parents (6% of reactions and 15% of near misses) reported misreading or misunderstanding the written information on the label or menu. For parents, significantly more reports of near misses than reactions attributed their incident to this cause (15% of near misses compared to 6% of reactions).

Also within the above percentage of consumer behaviour-related causes, 2% of adults (2% of both reactions and near misses) and 3% of parents (5% of reactions and 0% of near misses) reported ordering a vegan item thinking that it would be suitable for them.

5.2.4. Avoiding reactions

Participants who were reporting on a near miss to loose food, and therefore had avoided having a reaction, were asked to indicate how they had avoided having a reaction (N=138 adults and 67 parents). Most commonly, this was reported to be due to seeing the allergen in the food (40% of adults, 94% of parents/children). Participants also reported checking with the waiting staff that the food was allergen-free (36% of adults, 55% of parents/children) and that the person thought that they tasted the allergen and so stopped eating (33% of adults, 58% of children) (see Figure 14).

5.3. Reactions and near misses to packaged food (prepacked and PPDS)

This section reports on the experiences of adults and parents who said their or their child’s latest reaction/near miss was related to packaged food (30%, N=205 of adults and 50%, N=216 parents). For the purposes of this report, packaged food refers collectively to food packaged in a different location to where it was bought (prepacked food) and food packaged at the same place from which it was bought, prior to being ordered or selected by the customer (PPDS).

Adults and parents whose incident involved packaged food were more likely to report that this was involving prepacked food (56% of adults and 66% of parents) than food that was PPDS (36% of adults and 29% of parents).

5.3.1. Place and methods of purchase for packaged food

As could be expected, supermarkets were the most common place of purchase of the packaged food or drink which caused the latest incident (28% of adults and 33% of parents). For adults, this was followed by a takeaway (18%) and restaurant (17%), and for parents, a restaurant (27%) and a takeaway (11%). Other places such as a pub, plane/train, residential establishment, canteen, catered event or charity food sale were each reported by 7% participants or less. The most common places can be seen in Figure 15.

For adults, the packaged food/ drink involved in the incident was most commonly purchased or ordered in store by the FHS customer (26%).[12] This reflects the finding that food or drink was most commonly purchased from a supermarket. The next most common way of purchasing was a member of staff taking their order for them (19% N=30 out of 161). Parents were evenly split between reporting they or their child purchased the food or drink in a store themselves (28% N= 35 out of 127) and a member of staff taking their order for them (27% N=34 out of 127). The range of ways in which food or drink was purchased or ordered can be seen in Figure 16.

5.4. Outcomes of reactions and near misses

For those reporting a reaction to both food sold loose or packaged food 42% of adults (N=206 out of 486) and 28% (N=74 out of 265) did not treat the reaction with anything. For those treating the reaction, most adults (55%) and parents (65%) reported they used antihistamines. Adrenaline was reportedly self-administered by 21% of adults reporting a reaction and 17% said a paramedic, nurse or doctor gave them adrenaline. Self- or parent-administered adrenaline was reported for 27% of children who had a reaction, and 35% of parents said a paramedic, nurse or doctor gave their child adrenaline (see Figure 17 for the treatment options selected by adults and parents) (Tables A25 and 26 in Annex A contain further information on numbers and percentages).

Out of all adults who had a reaction to food sold loose or packaged food, 14% (N=66) reported that they had to call an ambulance and 20% (N=96) stated they had to go to hospital due to their reaction. Significantly more parents than adults said they had to call an ambulance for their child (35%, N=93) (χ2(1)=44.69, p<0.001) or that their child had to go to hospital (45%, N=120) (χ2(1)=50.70, p<0.001) due to their reaction.

Significantly more parents (63%) than adults (53%) made a complaint about their or their child’s reaction or near miss (χ2(1)=3.8, p=0.05). Out of those that did make a complaint, most were to the food provider (78% of adults and 68% of parents). Other places where complaints were made can be seen in Figures 18 and 19. (Tables A27 and 28 in Annex A contain further information on numbers and percentages). There were significant differences in the complaints made for a reaction compared to a near miss. More parents and adults made complaints to a doctor or health care professional for reactions compared to near misses (χ2(1)=9.59, p=0.002 for adults; χ2(1)=10.60, p=0.001 for parents). More parents made more complaints to the local authority for reactions compared to near misses (χ2(1)=7.21, p=0.007).

6. Conclusions

This report offers insight into the circumstances surrounding reactions and near misses to food or drink in people with food allergy, food intolerance or coeliac disease in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. This research focusses on the most recent FHS incident reported by adults with FHS and the parents of children with FHS in the last five years.

The research primarily reports on the experiences of consumers who purchased loose food, as this was the primary aim of research. Data was also collected on consumers who reported that their most recent incident was to packaged food (which includes PPDS and prepacked foods), however this is discussed in less detail due to it being a secondary objective.

6.1. A note on interpretation of results

When interpreting this research, it is important to consider the findings in light of sample of participants involved; those who have had either a reaction or a near miss in the last five years. The findings are based on self-reported data and should be interpreted with this in mind. The findings also rely on the accurate recollection of participants, and any causes or specific circumstances are not possible to verify. Although the majority of parents reported that they were with their child at the time of the incident (91% of near misses and 90% of reactions), a small proportion of parents will have been relying on accounts from their child or another person.

It should also be noted that responses relating to loose food are skewed to incidents which occurred in restaurants (40%), and to a lesser extent cafés (16%) and will therefore likely reflect the consumer ‘journey’ when purchasing food at these types of places.

Keeping the above caveats in mind, this report presents useful insight into the experiences and circumstances of individuals’ reactions and near misses.

6.2. Summary

This section summarises the key points made in the report.

Loose food was more likely than packaged food to be the cause of incidents for adults. Two-thirds of adults (67%) reported that their most recent FHS incidents was to loose food, compared to packaged food (30%). For parents, FHS incidents were relatively equally split between loose food (45%) and packaged food (50%). As could be expected, loose food was most commonly purchased in restaurants, and packaged food was most commonly purchased in supermarkets.

For businesses to be able to take reasonable precautions when serving consumers with FHS, it is important that they are aware of any requirements. This research has found that although the majority of both adults (82%) and parents (82%) reported disclosing their FHS requirements, 15% of both adults and parents reported that they (or their child) did not disclose their FHS requirements, even when asked. Furthermore, of those who disclosed, 7% reported that they felt the business didn’t understand their request.

FBOs are legally required to provide accurate allergen information on the 14 regulated allergens (in some form) to consumers. Consumers reported that some form of allergen information was provided in the majority of the reported incidents (75% of adults and 83% of parents).[13] 38% of adults and 46% of parents reported that allergen information was provided verbally and only 17% of adults and 16% of parents said allergen information was not visible.

Only a small minority of consumers reported that allergen information was not provided in response to a query (4% of adults and 3% of parents). Furthermore, only 1% of adults, and no parents attributed their FHS incident to asking for allergen information, and that this was not provided by the FBO. Although 15% of both adults and parents reported that the cause of their incident was due to there being no ingredients list provided, it is not a requirement for FBOs to provide consumers with this information for loose food.

Some businesses choose to provide confirmation to consumers that their FHS requirements have been met, although this isn’t a requirement. Of the participants who reported disclosing their FHS requirements, around two-thirds of adults (64%) and parents (67%) received confirmation that their needs had been met. Given that all of the sampled consumers ultimately experienced either a reaction or a near miss, this means that these instances of confirmation were given in error.

In terms of the causes of the reported FHS incidents, half of adults (51%) and over half (58%) of parents were attributed to errors made by businesses and staff.[14] The business errors include:

-

Errors in communication, with 17% of adults and 10% of parents reporting that their FHS requirements were not passed on to the person preparing their meal;

-

Consumers reporting being provided with the wrong meal or order (9% of adults and 15% of parents).

-

Some consumers reported issues with the accuracy of information provided to them: 13% of adults and 16% of parents said that they were given the wrong allergen information, 12% of adults and 14% of parents reported that the person who provided the food did not check the allergen information, and 9% of adults and 15% of parents said that food was incorrectly labelled.[15]

Although not a business error (and so not included in the above net), 3 in 10 said that the provided allergen information was difficult to understand (30% of adults and 27% of parents), suggesting further problems with the way allergen information is provided.

1 in 10 (12%) of adults and nearly 1 in 5 (17%) of parents reported causes related to consumer behaviour.[16] These include:

-

7% of adults and parents reported not checking the allergen information.

-

4% of adults and 10% of parents reported misreading or misunderstanding the written information on the label or menu.

-

2% of adults and 3% of parents reported ordering a vegan item thinking that it would be suitable for them.

Annexes

Annex A: Data Tables

Annex B: Statistical Analyses

Results of statistical analyses for comparisons of reasons for reactions compared to near misses for adults and parents reporting an incident to food sold loose

-

Significantly more adults reporting a near miss (22%) rather than a reaction (14%) said it was due to a member of staff not being aware of their FHS requirements despite informing them, (χ2(1)=4.10, p=0.043).

-

Significantly more adults reporting a near miss (17%) rather than a reaction (9%) said the person providing the food did not check the allergen information, (χ2(1)=6.88, p=0.009).

-

Significantly more adults reporting a near miss (21%) rather than a reaction (11%) said they received the wrong order or wrong meal, (χ2(1)=6.79, p=0.009).

-

Significantly more parents reporting a near miss (24%) compared to a reaction (9%) thought it was due to a lack of ingredients list, (χ2(1)=6.58, p=0.01).

-

Significantly more parents reporting a near miss (15%) compared to a reaction (6%) thought it was due to misreading or misunderstanding the label, (χ2(1)=3.72, p=0.05).

-

Significantly more participants reporting a reaction (31% for adults, 40% for parents) compared to a near miss (15% for adults, 12% for parents) thought that it was due to cross-contamination, (χ2(1)=13.14, p<0.001 for adults; (χ2(1)=18.74, p<0.001 for parents).

Allergen guidance for food businesses | Food Standards Agency

This includes: verbally by staff/ on a specific menu/ present on all menus/ on a separate allergen matrix/ menu was edited/ on a sign close to the food/ provided on an app or website.

This includes 13% of adults and 16% of parents who attributed their FHS incident to being given incorrect information by staff, and 9% of adults and 15% of parents who reported that their incident was due, at least partially, to incorrectly labelled food.

Due to the question phrasing, it is not known if these consumers disclosed proactively or in response to being asked.

Allergen guidance for food businesses | Food Standards Agency

This question was only asked of consumers who said that allergen information was visible

9% of all adults (N=58) and 8% of all parents (N=34) said that this incident was the first time they became aware of having an FHS. They were therefore not asked about provision of allergen information.

(χ2(1)=21.72, p<0.001). Moderate and mild participants were combined to form one group to allow for sufficient sample size for significance testing.

(χ2(1)=4.65, p=0.03. Note that the number of adults in the younger age group are much smaller than the older age group, therefore this finding should be treated with caution. There were no associations across age categories for children regarding whether the parent or child told the food business about dietary or allergy requirements.

This includes: the participant providing information but staff who prepared the meal were not aware of the FHS requirements; wrong order or meal received; staff gave incorrect information; person who provided the food did not check the allergen information; incorrectly labelled

This was a net of the proportions of consumers reporting that their FHS incident was caused, at least partially, by the following causes: Not checking the allergen information, misreading or misunderstanding the written information on the label/ menu, and, ordering a vegan item thinking it would be suitable.

Sample for this question was those who were involved in ordering or purchasing the food (where the food was not provided at the home of family or friends). N=41 out of 161.

This refers to allergen information and in general, and it’s possible that participants were not provided with the specific information that they needed.