1. Introduction

1.1. Contextual background

Food eaten out of the home makes up an increasing proportion of people’s dietary intakes. According to the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), in 2019-20, around 30% of spend on food in the United Kingdom (UK) was on food eaten out of the home. Food eaten out of the home tends to come in larger portion sizes and is usually higher in energy, saturated fat, salt and sugar, and lower in fruit and vegetables than meals prepared at home (World Health Organization, 2021).

Research shows that there are a limited number of meal options on children’s menus, with few healthy options included (Food Standards Agency, 2024; Safefood, 2013). Analysis of children’s menus from restaurants across Northern Ireland (NI) showed that vegetables were only served with one quarter (24%) of meals (FSA, 2024). Nutritional sampling of children’s meals shows that popular children’s meals tend to be high in energy, saturated fat and salt.

Evidence from the National Diet and Nutrition Survey (2012-2017) supports this, as results have shown that children in NI are consuming too much saturated fat and free sugars. Given the high proportion of households eating out of the home, alongside the poor nutritional quality of children’s meals offered in NI, these meals could be contributing to the overconsumption of saturated fat and sugar observed among children in NI.

The FSA in NI have a remit for dietary health policy, with one of the current policy focuses being to work with industry to improve the nutritional quality of offerings for children when eating out of the home.

The findings of this literature review will be used to build an evidence base to inform further work in creating a healthier food environment for children in NI.

1.2. Aims and objectives

The aims and objectives of this literature review are to investigate the effectiveness of restaurant initiatives to improve the nutritional content of children’s meals offered, and to promote positive behaviour change in consumers (i.e. parents and children) when choosing meals for children.

The specific research objectives of this literature review are to:

-

Explore the effectiveness of initiatives to improve the nutritional content of children’s meals.

-

Explore the effectiveness of initiatives that encourage consumers (parents and children) to order healthier children’s meals.

-

Determine what motivates food businesses to participate in initiatives to improve nutritional content of children’s meals and understand the barriers to participation.

-

Establish if existing evidence has considered the impact of such interventions on profitability and food waste and what conclusions have been reached.

For this literature review, healthier children’s meals include those which, as a result of an intervention, may have any of the following:

-

higher fruit or vegetable content, compared to meals pre-intervention;

-

higher fibre content from starchy or wholegrain carbohydrates such as pasta, rice or (non-fried) potatoes, with less or no added fat, compared to meals pre-intervention;

-

reduced sugar, saturated fat or salt levels, compared to meals pre-intervention;

-

are not fried, or use alternative cooking methods (grilling, baking) or, if fried, use healthier cooking oils (sunflower or rapeseed), compared to meals pre-intervention.

2. Methods

The methodology employed for this literature review is a Rapid Evidence Assessment (REA) based on a systematic search.

2.1. Search strategy

Primary searches for this project were conducted using SCOPUS, PubMed and Cochrane Library. Searches were conducted between 27th and 29th November 2024.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria used for the selection of eligible articles were as follows: Primary research on food business outlets within the ‘out of home’ sector; Primary research exploring initiatives to improve the nutritional offering and uptake of healthier meals for children aged 12 or under; High-quality, original research papers and academic articles; Articles published in English; Articles published in the last 10 years.

2.3. Screening

Results from the database searches were organised into a single literature collation spreadsheet. Screening of articles was undertaken independently by two researchers and was based on the title and abstract of each source.

2.4. Data extraction

Data were extracted from included studies using a bespoke Data Extraction and Analysis Spreadsheet. A populated version of the Data Extraction and Analysis Spreadsheet is available as Annex 2 of this report.

2.5. Data analysis

Data were analysed using content analysis, which consisted of identification of a series of categories (or codes) for different types of interventions and outcomes.

2.6. Quality assessment of sources

The quality of evidence was assessed using a hybrid framework which draws upon the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline checklists for assessing risk of bias in evidence, combined with the GRADE framework for assessing the quality of evidence.

3. Results

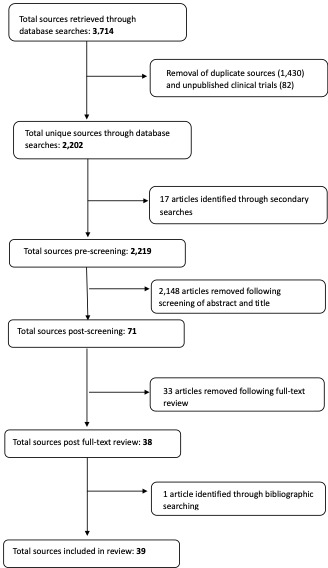

Primary searches generated a total of 3,714 studies. Following removal of duplicates, 2,219 unique sources were identified.

Screening of article titles and abstracts revealed 71 potentially relevant articles. Full-text review of the 71 articles identified 38 articles that met the inclusion criteria of this literature review. One additional source was identified through bibliographic searching, taking the final number of included studies to 39. The full screening process is set out in the flow diagram in Figure 1.

An overview of the 39 studies in scope of this literature review is included in Appendix 3.

Grey literature searches did not reveal any studies which met the inclusion criteria.

A breakdown of the included studies by objective is included in Table 1.

Most of the included studies (n=33) were conducted in the United States of America (USA); 2 in Germany, and 1 study in Australia. Three of the included studies were literature reviews based on studies conducted across multiple countries.

The majority (n=16) of the identified studies are cohort studies which examined the effect of an intervention on different groups (consumers and restaurants), comparing the outcomes post intervention against pre-intervention baseline data. Seven of the studies are quasi-experimental studies. Two of these compared outcomes of an intervention group against a control group, but without randomisation. Five compared the outcomes of different intervention conditions on different groups, but without a control group.

Three randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were identified, which compared the outcomes for an intervention group against a control group, into which participants were randomly assigned.

3.1. Objective 1: Initiatives to improve the nutritional content of children’s restaurant meals

Twelve studies were identified that relate to objective 1: Initiatives to improve the nutritional content of children’s restaurant meals. Of these, 7 examined the impact of mandatory legislation, 4 studies examined the impact of voluntary recognition schemes and 2 examined the impact of community interventions.

3.1.1. Mandatory legislation

Of the studies that examined the impact of mandatory legislation, 3 (Powell et al., 2023, 2024; Ritchie et al., 2022) examined the impact of different healthy default drink (HDD) acts on children’s drink offerings in restaurants. Three studies (Bleich et al., 2015; Wellard-Cole et al., 2019; Wu & Sturm, 2014) explored the impact of calorie labelling laws on the nutritional content of children’s restaurant meals and 1 study (Otten et al., 2014) examined the impact of banning the offering of free toys with unhealthy children’s meals.

Healthy default drink (HDD) acts

Three studies were identified that examined the impact of healthy default drink (HDD) acts on children’s drink offerings in restaurants. (Powell et al., 2023, 2024; Ritchie et al., 2022)

Powell et al., 2023 and Powell et al., 2024 examined default drinks offered with children’s meals in a sample of fast-food restaurants in Illinois, USA before and after implementation of a HDD act (the Illinois Healthy Default Beverages (HDB) Act), compared to fast-food restaurants in a control state which did not have a HDD act in place. Powell et al., 2023 analysed changes in default drink offerings at 4 months post implementation and Powell et al., 2024 explored changes at one year. Both studies were primarily concerned with examining the extent of restaurant compliance with the HDD acts, rather than the impact of the acts on the nutritional content of children’s drinks.

Powell et al., 2023 collected data on default drinks offered with children’s meals from 121 restaurant websites and restaurant applications. Data was collected at baseline in November 2021 (before the Illinois HDD act came into effect), then again in May 2022 (4 months after implementation). No statistically significant changes in children’s drink offerings were found in fast-food restaurants in Illinois, 4 months after the Illinois HDD act came into effect, compared to those in Wisconsin.

Similar findings were also found at one year post implementation (Powell et al., 2024). Data were taken from 98 interior menu boards, 79 drive-thru menu boards, 110 restaurant website/applications, and a range of third-party ordering platforms. No statistically significant changes in children’s default drink offerings were found at fast-food restaurants one year after the HDD act came into effect in Illinois, relative to Wisconsin.

The main limitation with both Powell et al., 2023 and Powell et al., 2024 is that the primary study objective was to assess compliance with the act; the studies are less concerned with assessing the effectiveness of the acts in improving the nutritional value of children’s drink offerings. Furthermore, while both studies compared changes in Illinois against a control state, the lack of an experimental design means that the researchers had limited control over the variable under examination, meaning that restaurants could not be randomised into control or intervention conditions.

Ritchie et al., 2022 analysed changes in the default drinks offered with children’s meals at fast-food restaurants in California and in the city of Wilmington. Data were collected one month prior to, and 9 to 12 months after, HDD policies came into force in both jurisdictions. While there was a significant increase in the proportion of restaurants in California offering only healthier, policy-compliant drinks (increase from 9.7% to 66.1%, p < 0·0001), there was a significant decrease in the proportion of healthier, policy-compliant drinks offered by default by cashiers. There was no change in the proportion of restaurants offering only policy-compliant drinks in Wilmington (30.8% before and after policy implementation).

While this study had a moderate sample size (110 restaurants in California, and all (14) restaurants in Wilmington which were affected by the city’s HDD policy), the lack of a control jurisdiction means that there is no way of knowing whether the positive trends observed in California were also taking place in other areas, including those without HDD policies.

Evidence from the 3 studies which examined the impact of HDD acts found no association between the implementation of HDD acts and improvements in drink offerings on children’s menus in fast-food restaurants. However, studies were primarily concerned with examining the extent of restaurant compliance with HDD policies, rather than the impact of HDD laws on health outcomes.

Calorie labelling laws

Three studies (Bleich et al., 2015; Wellard-Cole et al., 2019; Wu & Sturm, 2014) explored the impact of calorie labelling laws on the nutritional content of children’s restaurant meals.

Wu & Sturm, 2014 analysed changes in the energy and sodium content of main meals (including children’s main meals) at 213 top chain restaurants in the United States of America (USA) immediately following the passage of the 2010 United States Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (US ACA). The act introduced a legal requirement for large restaurants to provide calorie information on their menus. Data were collected in 2010, the year in which the US ACA was passed, and 2011. There was a reduction in the mean energy content of children’s meals in fast-food restaurants between 2010 and 2011 (-40 kcal; p=0.049). However, when data from all restaurant types were combined, changes in the energy and sodium content of children’s meals were not significant (mean energy content of meals in 2010 = 462 kcal, in 2011 = 468 kcal; mean sodium content of meals in 2010 = 951 mg (2.4 g salt), in 2011 = 932 mg (2.3 g salt)).

Bleich et al. (2015) analysed changes in energy content of menu items at 66 of the 100 largest chain restaurants in the USA, in the years 2012 and 2013, following the passage of the US ACA. No statistically significant changes were found in the calories of new children’s menu items introduced in 2013, relative to menu items in 2012 (-46 calories, p=0.36). Similarly, no statistically significant changes were found when all children’s menu items in 2013 (not just the new ones) were compared with children’s menu items in 2012 (-0.5 calories, p=0.67).

Findings from both Wu and Sturm (2014) and Bleich et al. (2015) show that there were minimal overall reductions in the energy and salt content of children’s meals, at large restaurant chains in the USA, immediately following the implementation of mandatory calorie labelling. The main limitations of both studies are that data were collected from only two points in time and from large chain restaurants only, so findings cannot be generalised to smaller or independent restaurants.

Wellard-Cole et al. (2019) analysed the nutrient composition of children’s meals at Australian fast-food restaurants. Data from 289 children’s meals, covering 12 fast-food restaurant chains, were collected for 2016 and compared against baseline data from 2010 (before mandatory calorie labelling was introduced). There were no significant overall changes in the mean energy (2010 mean = 2174 KJ; 2016 mean = 2184 KJ), saturated fat (2010 mean = 5.5 g; 2016 mean = 5.3 g), sugar (2010 mean = 28.6 g; 2016 mean = 28.6 g) and sodium (2010 mean = 666 mg; 2016 mean = 655 mg) content of children’s fast-food meals in 2016 compared to 2010. There were also no significant changes in the proportion of children’s meals that exceeded either 30% or 100% of the recommended energy and nutrient intake for children.

Evidence from the 3 studies which examined the impact of calorie labelling laws found no association between calorie labelling and improvements in the nutritional quality of children’s meals. However, all 3 studies are based on data taken from large chain restaurants, so findings may not be relevant to all restaurant types.

Toy ordinance laws

Otten et al., 2014 analysed the energy and nutritional content of children’s meals at 2 global chain restaurants operating in San Francisco, before and after implementation of the San Francisco Toy Ordinance. The Ordinance prohibited restaurants from giving away toys with children’s meals unless certain nutritional criteria were met. While the Ordinance did prompt the 2 restaurant chains to make small reductions in the energy, fat and salt content of children’s menu items, improvements were limited and not sufficient to bring children’s meals into compliance with the nutritional criteria set by the Ordinance.

The main limitation with Otten et al., 2014 is that the study analysed changes made by only 2 restaurant chains (Chain A n=19; Chain B n=11) and did not include comparison against a control group.

3.1.2. Nutritional standards

Voluntary recognition schemes and standards

Four studies were identified which examined the effect of participation in voluntary recognition schemes on improving the nutritional content of children’s menu items (Gase et al., 2015; Harpainter et al., 2020; Moran et al., 2017; Wellard-Cole et al., 2019).

Harpainter et al. (2020) examined drinks offered with children’s meals at 111 fast-food restaurants in California. Restaurants which had introduced voluntary children’s healthy default drinks policies (n=70) were compared against those which had not (n=41). Restaurants with standards were more likely to offer healthier drink options – such as unflavoured milk (92.0% compared to 43.2%; p = 0.005) and water (60.0% compared to 32.6%; p = 0.036), and less likely to offer sugar-sweetened drinks (29.1% compared with 38.6%; p = 0.351), when compared to restaurants without standards. However, standards were less likely to influence cashiers to offer only healthier children’s drink options by default.

The principal limitation with this study is that the restaurants selected were drawn from a convenience sample of low-income communities in 11 California counties, meaning that results may not be generalisable to all quick service restaurants.

Gase et al. (2015) examined the impact of the Choose Health LA Restaurants programme, a voluntary reformulation programme in which participating restaurants must meet specific criteria in their children’s meals. The menus of 10 participating restaurants that offered children’s meals were compared before and after participation in the programme. Of the 10 participating restaurant brands, 8 made changes to their children’s meals. Five changed the type of drinks included with children’s meals to “healthy” drinks (based on programme criteria); 7 changed their meal offerings to include at least one non-fried fruit or vegetable as the default meal side and a further 6 reduced the number of children’s meals containing fried foods.

While these findings may be positive, due to a small convenience sample, and a lack of comparison against a control group, it is difficult to attribute these positive outcomes in children’s menu reformulation to the implementation of the programme alone.

Moran et al. (2017) analysed trends in the nutrient content of 4,016 children’s menu items in 45 of the top 100 US restaurant chains. Data were collected from the first 4 years following implementation of the US National Restaurant Association’s Kids Live Well (KLW) standards in 2011 (2012, 2013, 2014 and 2015). There were no substantial changes in the energy, salt or saturated fat content of children’s menu items, in the 4 years following the implementation of the KLW standards. No significant changes were found in calories in children’s drink offerings between 2012 and 2015, nor in the calories of children’s main meals, among KLW restaurants, between 2012 and 2015.

The main limitation with Moran et al. is that the study included only 15 restaurants participating in the KLW standards, which represents only a small fraction of the 150 restaurants participating in the standards at the time.

Wellard-Cole et al. (2019) examined the effectiveness of the Australian Quick Service Restaurant Industry (QSRI) Initiative for Responsible Advertising and Marketing to Children. They analysed the proportion of meals served at participating QSRI restaurants which met QSRI criteria. Based on an analysis of 172 children’s meals from 6 QSRI signatory chains, findings show that 82% of meals exceeded the nutrient criteria for energy, saturated fat, sugar and salt, for 4- to 8-year-old children, while 76% of meals exceeded the criteria for 9- to 13-year-olds. Based on these findings, the authors state that the majority of children’s meals served in QSRI chains did not meet the industry’s own definition of a healthy children’s meal.

Findings from the 4 studies show that while voluntary nutritional standards are associated with some positive changes in the quality of children’s menu items, changes are often limited in scale or not implemented consistently across restaurants.

Community interventions

Two studies were identified which examined the impact of community interventions on improving the nutritional content of children’s restaurant meals (Crixell et al., 2014; Redelfs et al., 2021).

Crixell et al. (2014) reported on the Best Food for Families, Infants, and Toddlers (Best Food FITS) project in San Marcos, Texas (2010 to 2014). The aim of this intervention was to enhance children’s access to healthy foods by working closely with local San Marcos restaurants, helping them to improve their children’s menus by removing sugar-sweetened drinks, limiting offerings of energy-dense mains, and increasing offerings of fruit and vegetables. In total, 17 restaurants participated and all restaurants successfully made their children’s menus healthier. The 17 participating restaurants removed all sugar-sweetened drinks from their children’s menus, as well as reducing the number of fried, cheesy, greasy or fatty mains (average of 3.08 on pre-intervention menus; 0.24 post intervention, p = 0.04) and sides (average of 2.04 pre-intervention; 1.18 post-intervention, p = < 0.001). The 17 participating restaurants also increased the number of healthy mains (average of 2.02 pre-intervention; 4.12 post-intervention, p = < 0.001) and healthy vegetable side dishes (average of 1.08 pre-intervention; 3.24 post-intervention, p = < 0.001) on their menus.

Children’s menus were also assessed using a Children’s Menu Assessment system, a tool developed by Krukowski et al. (2011) which calculates an overall children’s menu score based on an assessment of 12 items (including availability of healthy mains, free refills on sugar-sweetened drinks, fruit and vegetable offerings). Compared to menus assessed pre-intervention, the mean children’s menu assessment score for the 17 participating restaurants was significantly higher (mean of 1.85 pre-intervention; 8.53 post-intervention, p=< .001). This suggests that the menus of the 17 restaurants which participated in the intervention were significantly healthier than menus assessed pre-intervention.

The principal limitation with the Best Food FITS intervention was its small sample size and low participation rate. 24% of the 70 non-chain restaurants that did not participate cite corporate policy as a barrier.

Redelfs et al. (2021) reported on the Eat Well El Paso! (EWEP) project (2012-2017). This project was a local community initiative funded by the Department of Public Health of El Paso, Texas, which involved working with local restaurants to help them offer healthier children’s and adult’s meals.

Redelfs et al. report broad statistics about participation rates and did not analyse the nutritional content of meals pre or post intervention. In the last 2 years of the intervention (2016 and 2017), there were 26 restaurants involved in the EWEP project (no information is provided about the total restaurant population or the total number of restaurants approached) and 24 additional children’s menu items were created. Of these 26 restaurants, 21 (81%) fully completed the onboarding process.

Redelfs et al. also provide a series of lessons learned which emphasise the value that can be gained through a collaborative approach to working with a small number of independent restaurants:

-

High-quality engagement and depth of support should be prioritised over attempting to achieve a high number of participating restaurants.

-

Restaurant buy-in and support for the intervention is more likely when a restaurant is well-established, the owner is involved, and when owners have an interest in promoting health.

-

An understanding of restaurant culture by intervention teams is critical.

The principal limitation with this study is that it only explores participation rates. The study does not explore impacts of the intervention on health outcomes, such as the nutritional content of meals served by participating restaurants post intervention.

Studies of 2 community interventions have reported some limited evidence of success in encouraging independently owned restaurants to improve the nutritional quality of their children’s menu items by engaging with them directly.

3.2. Objective 2: Initiatives to encourage consumers (parents and children) to order healthier meals in restaurants

Twenty-four studies were identified that relate to objective 2: Initiatives to encourage consumers (parents and children) to order healthier meals in restaurants. Of these, 6 examined the impact of calorie labelling, 10 studies examined the impact of optimal defaults, 4 studies examined the impact of signposting interventions, 3 studies examined the impact of incentives, and 2 examined the impact of social marketing techniques.

3.2.1. Calorie labelling

Six studies were identified which explored the effectiveness of calorie labelling initiatives in encouraging parents and children to order healthier restaurant meals (Downs & Demmler, 2020; Nguyen et al., 2021; Petimar et al., 2019, 2020; Sacco et al., 2017; Todd et al., 2021).

Petimar et al. (2019) examined the calorie content of meals purchased for adults, adolescents and children (aged between 3 and 15), at McDonald’s restaurants in 4 US cities. Data were collected before and after McDonald’s implemented voluntary calorie labelling (between 2010 and 2014) and comparisons were made against 5 control restaurant chains that did not label their menus over this period. While the calorie content of meals purchased for children decreased in McDonald’s following the implementation of calorie labelling (-158 calories), similar changes were also found in the 5 restaurants which did not implement calorie labelling (-159 calories). Calorie labelling was therefore not associated with changes in the calorie content of meals purchased for children.

In a similar study, Petimar et al. (2020) examined the impact of calorie labelling on the nutritional content of meals purchased in adults, adolescents, and children in 4 New England cities (USA), from 2010 to 2014 in McDonald’s, compared to 5 control restaurant chains. In McDonalds, while absolute saturated fat (-0.8 g), sugar (-10.2 g) and sodium (-143 mg) content of children’s meals purchased decreased after calorie labelling, they also decreased in the 5 control restaurants (saturated fat: -2.7 g; sugars: -10.8 g; sodium: -334 mg). Meals purchased for children at McDonald’s also had lower dietary fibre content (-0.9 g) and lower fibre density (calculated as the fibre content per 100 calories: -0.04 g), following the introduction of calorie labelling, compared to other chains, suggesting a potential adverse, unintended consequence of menu labelling.

While both Petimar et al. (2019) and Petimar et al. (2020) had a large sample of children (447 children in 2019, and 433 children in 2020), in both cases, recruitment of study participants involved approaching customers as they entered the restaurant. Participation rates were >50% across all samples, which introduces the risk of selective sampling.

Sacco et al. (2017) conducted a systematic review to examine the influence of different calorie labelling formats on calories ordered by children and adolescents (or parents and guardians for their children) in different food outlets. The review included studies which tested the impact of menus displaying numeric calorie information only; menus displaying calorie content with additional nutrition information, such as fat content; menus with traffic light representations indicating high/moderate/low levels of calories, and menus displaying calories and a physical activity equivalent, showing the walking distance or time needed to burn the item’s calorie content. Two natural experiments, reported by Sacco et al., which examined the impact of calorie labelling in fast-food chain restaurants, found no statistically significant effects of calorie labelling compared to control outlets. This contrasts with school cafeterias, where calorie labelling was found to be effective. The review found that, in real world settings, calorie labelling had a limited effect on purchasing behaviours amongst children (or parents and guardians).

Findings are also supported by 2 other literature reviews. Downs and Demmler (2020) conducted a scoping review examining the impact of different food environment interventions, including calorie labelling, on the diets and nutritional outcomes of children and adolescents. The review found mixed and limited results on the impact of calorie labelling on the food choices.

Nguyen et al. (2021) conducted a rapid evidence review on the effectiveness of Numeric Energy Menu Labelling (NEML) on different consumers, including adults, adolescents and children. One study, reported by Nguyen et al. (2021), found that while NEML appeared to be effective at encouraging children to order meals with fewer calories in artificial settings, the evidence for the effectiveness of NEML was less clear in real-world restaurant settings. Nguyen et al. (2021) therefore found mixed and inconclusive evidence in relation to the effectiveness of calorie labelling strategies for children when ordering restaurant meal items.

Todd et al. (2021) examined the relationship between local and state-level calorie labelling laws in the United States of America (USA) and calorie intake from meals consumed outside of the home by children. Data were taken from the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and combined with geographical analysis of US states and regions with calorie labelling laws. For children aged 2-12, where each meal consumed outside of the home adds 159 calories to daily intake, this effect is reduced by 34 calories for each year that a calorie labelling law is in place.

The main limitation with Todd et al. (2021) is that the study only explores associations between menu labelling laws and dietary intake from meals consumed outside of the home; it does not explore the choices being made by consumers and so cannot comment on whether the reported calorie reductions are caused by consumers ordering lower calorie meals, or restaurants reducing the calorie contents of meals.

Evidence from the 6 studies summarised above found no association between calorie labelling and changes in the ordering behaviour of parents or children in restaurants.

3.2.2. Optimal defaults

Ten studies were identified which explored the effectiveness of optimal defaults in encouraging parents and children to order healthier restaurant meals (Anzman-Frasca, Mueller, Sliwa, et al., 2015, 2015; Choi et al., 2021; Dalrymple et al., 2020; Ferrante et al., 2019, 2022; Mueller et al., 2017; Peters et al., 2016; Wansink & Hanks, 2014; Wansink & Just, 2016). An optimal default is an option that maximises welfare or, in the case of food choices, prioritises a healthier option. Optimal defaults are an important feature of many voluntary recognition initiatives.

Dalrymple et al., 2020 tested the impact of 3 different menu presentations on children’s main meal and side orders in 2 theme park restaurants in the USA. The 3 menus were randomly assigned to each restaurant for week-long intervals, over 3 consecutive weeks. Sales data were then collated and analysed. The 3 menu conditions were:

-

An Optimal Default Menu, which presented healthier, lower energy-dense options as the default options;

-

A Suboptimal Default Menu, which presented less healthy, higher-calorie options as the default options, and

-

A “Free Array Menu”, which acted as a control.

Menu presentations which positioned less-energy-dense items as the default options increased the likelihood of consumers (parents and children) ordering less-energy-dense meals. During the Optimal Default Menu condition, 49.8% of children’s main meals and 42.2% of children’s sides were less-energy-dense (compared to 15.4% of mains and 6.1% of sides in the Suboptimal Default Menu condition; 27.0% of mains and 18.1% of sides in the Free Array Menu condition). Dalrymple et al.‘s study offers strong evidence that optimal defaults can encourage healthier (lower energy-dense) choices for kids’ meals. This is because the study benefitted from a strong study design with a large number of orders analysed, randomisation of 3 menu conditions and a control group in the form of the diners who received the control menu condition.

Anzman-Frasca, Mueller, Sliwa, et al., 2015 examined changes in children’s meal orders at 13 outlets of a regional US full-service restaurant chain (Silver Diner), following implementation of the National Restaurant Association’s Kids Live Well (KLW) standards. Sales data from the 13 outlets were collected at baseline and after implementation of the healthier menu. Orders of healthy children’s main meals (children’s meals which met KLW nutrition standards) increased following introduction of the healthier children’s menu (from 3% of orders pre-intervention, to 46% of orders post intervention). There were also increases in orders of strawberry (29% to 63% of children’s orders) and vegetable (5% to 7% of orders) default sides and decreases in orders of French fries (57% to 22% of orders).

In a follow-up study, Anzman-Frasca, Mueller, Lynskey, et al., 2015 analysed sales data from the same restaurant chain at one- and two-year follow up periods. Sales data at the one- and two-year follow-up were compared against pre- and post-intervention data. Orders of healthier children’s main meals (45% at one year follow up, 43% at two year follow up) were largely sustained over the study period. The percentage of healthy default sides remained at, or above, 74% at both follow-up points. Orders of French fries (20% at the one year follow up, 21% at the two year follow up) and fizzy drinks (25% at first year follow up, 24% at second year follow up) also remained low.

Mueller at al., 2017 carried out a further follow-up study, based on the same restaurant chain. Itemised receipt data from all 13 outlets of the restaurant chain, between September 2012 and March 2013, were analysed. Analysis showed that healthier meal patterns (which included children’s main meals which met the KLW standards and healthier sides) accounted for 57.9% of all children’s orders.

While findings from studies of the Silver Diner restaurant chain are positive, these findings are based on sales data from only one restaurant chain and there is no control group. Therefore, it cannot be concluded with certainty that the observed trends can be attributed to the new menu.

Ferrante et al., 2019 examined the effect of a “vegetable-first optimal default” (offering a vegetable appetiser to children prior to the main meal) on children’s carrot intake during a restaurant meal. One group of families (n=19) attended 3 dinners at a restaurant on a university campus, spaced one week apart. During meals 2 and 3 (the optimal default conditions), children were given raw carrot sticks and ranch dressing as an appetiser, before the meal (meal 1 was a control condition in which children were not presented with carrot sticks). The study found a significant increase in carrot intake by children between the meals 1 and 2, but no significant increase in carrot intake between meals 2 and 3 (meal 1 mean carrot intake = 28.3 kcal; meal 2 mean = 33.9 kcal; meal 3 mean = 34.0 kcal).

While Ferrante at al. report positive results in terms of an increase in children’s vegetable consumption, the study was based on a small sample of families (n=19, 33 parents with a total of 34 children) and there was also no control group. The study was set in a university restaurant which was set up to mimic a real, commercial restaurant setting. While the families still dined, it is possible that the partially simulated setting may have impacted consumer behaviour.

Wansink & Hanks, 2014 explored the impact of McDonald’s policy of changing the default side options on Happy Meals (reducing the portion of fries and adding a side of apple slices and discontinuing the caramel dipping sauce) on the calorie composition of children’s meals. Analysis of sales data, from 2011 and 2012, for 30 McDonald’s restaurants, revealed that the policy of providing a healthier default side resulted in an average of 18.8% fewer calories per meal.

The principal limitation with this study is that it lacked a control group. This means that there is no way of knowing definitively if the reductions in calories sold can be attributed to McDonald’s optimal default policy, or if they were part of a general trend in children’s fast food restaurant meals in this period.

Peters et al., 2016 explored the impact of healthy default sides and beverages implemented at Walt Disney restaurants. The study examined orders of kids’ meals with a healthy side and drink, compared to orders of kids’ meals with a “classic side and drink”. Sales data for kids’ menu items for the 145 restaurants (94 fast-food restaurants and 51 full-service restaurants) located at Walt Disney World (WDW) Resort, USA, were provided and analysed from 2009 to 2012. This means that data analysis started 3 years after optimal defaults were first introduced in WDW restaurants in 2006. Results showed that 66.3% of all orders, over this time period, included healthy default beverages (compared to 33.7% of orders which included a “classic drink”), while 47.9% of orders included healthy default sides (52.1% of orders included a “classic side”).

While Peters et al. report positive findings, the researchers are unclear on the sample size and data were only provided from 2009 onwards. Data for the first 3 years of optimal default implementation are, therefore, not provided, which invites the possibility of selective reporting.

Ferrante et al., 2022 examined the impact of vice-virtue bundles (children’s meal combinations which include both a healthy and unhealthy side) on the ordering behaviour of parents and children, and on children’s consumption of healthy sides (carrots) and less healthy sides (French fries). The study tested 3 menu conditions on 2 cohorts of families. The menu conditions were as follows:

-

Menu 1 included an optimal default – a side serving of carrots (150 g);

-

Menu 2 served an optimal, vice-virtue default – a large side of carrots (100 g) and small serving of French fries (50 g);

-

Menu 3 served a suboptimal, vice-virtue default – a small side of carrots (50 g) and a large serving of French fries (100 g).

The study found that altering the choice architecture of the menu had negligible impact on the children’s carrot intake (menu 1 mean carrot intake = 37.7g; menu 2 mean carrot intake = 35.2g; menu 3 mean carrot intake = 29.3g), but it had a positive impact on reducing children’s intake of French fries.

Choi et al. (2021) conducted a repeated cross-sectional survey of 2,093 US caregivers who had purchased a fast-food meal for their children in the week prior to the survey. The study found no evidence that caregivers were more likely to select a healthier drink with a kids’ meal in restaurants with a healthy default drink policy (odds ratio = 0.75 (CI: 0.33-1.72), p=0.503), but they were more likely to select a healthier side in restaurants with a healthy default policy (odds ratio = 14.01 (CI: 7.45-26.33) p=<0.001).

A field experiment by Wansink (2016) found that the offer of a healthy default side (apple slices) to children had no impact on the consumption of either French fries or apple by the children. Results from the experiment showed that, when French fries were the default option, only one of 15 children chose to substitute French fries for apple slices (6.7%). However, when apple slices were the default, all but 2 children chose to substitute apple slices for French fries (86.7%).

While this experiment may be useful in highlighting the limits of optimal defaults, the sample of children (n= 15) was very small, there was no control group, and the experiment was based heavily on an ‘endowment principle’ which emphasises giving the subjects considerable power to consider their choice. If the children had been made less aware of the alternatives, it is possible fewer would have elected to swap apple slices for French fries.

The 10 studies which examined optimal defaults reported mixed and variable findings about the impact of optimal defaults on encouraging children and parents to order healthier restaurant meals. The strongest evidence relates to menu presentation which prioritise less-energy-dense items as default options. Studies of US restaurants which have adopted the KLW standards provide evidence that optimal defaults are associated with healthier ordering patterns by parents and children.

3.2.3. Signposting initiatives

Signposting interventions can come in the form of in-restaurant signage, advertising healthier menu options; pictures on menus which are appealing to children, guiding them to healthier options; or verbal prompts from serving staff. These types of intervention can also be called ‘nudging’.

Four studies were identified which examined the impact of in-restaurant signposting initiatives on encouraging healthier ordering habits by parents and children (Anzman-Frasca et al., 2018; Ayala et al., 2017; Lopez et al., 2017; Schneider et al., 2022).

Ayala et al., 2017 reported on the Kids’ Choice Restaurant Programme (KCRP). Eight independent restaurants in San Diego, USA, were randomised into a “menu-only” control condition and a “menu-plus” intervention condition. The 4 restaurants in the “menu-only” condition developed a new menu with healthier children’s meal options. The 4 restaurants in the “menu-plus” condition developed the new menu, as well as receiving in-restaurant signage to promote the healthier items. Weekly sales data were collected from the 8 restaurants before, during and after the intervention period. While sales of new healthier children’s items occurred immediately in both conditions during the intervention period, there was a significant downward trend in sales of new healthy children’s menu items over the whole study period (average weekly sales declined by $3.20; p = 0.004), in both conditions, with the most significant decline taking place in the post-intervention period.

Restaurant compliance with the initiative is likely to have impacted on the results. In the “menu-plus condition”, one of the restaurants was reluctant to display the signage and promotional materials. When this restaurant was excluded from the analyses, sales of the healthy children’s meals were significantly higher in “menu-plus” than in the “menu-only” restaurants, suggesting that when the menu-plus intervention was delivered as intended, the signposting elements had a positive impact on sales.

Lopez et al., 2017 explored the impact of a multi-component intervention (consisting of free promotional toys, placemats, verbal prompts from waiting staff, and in-restaurant signage) on the sales of healthier children’s menu items (defined as those which meet the KLW standards) in 4 US national chain restaurant locations (two fast-food restaurants; two full-service restaurants). Sales of healthier (KLW) children’s meals increased significantly in the full-service restaurants from baseline (5% of sales) to month 1 (8.3% of sales, p<0.05), before falling in month 2 (6.4% of sales). In the quick-service restaurants, sales of healthier (KLW) children’s meals decreased significantly over the 8 week intervention period (from 27.5% of sales at baseline to 25.9% of sales at month 2, p<0.5).

Like the KCRP, there were issues around restaurant compliance. Lopez et al. reported that the placemats promoting the KLW meals were not consistently distributed to families prior to meal selections. KLW meals were also not marked on menus, and the sign promoting the KLW meals, while visible, was smaller than other promotional signage in the restaurants, which reduced the impact of the intervention. Verbal prompting from waiting staff was also poorly implemented.

Anzman-Frasca et al., 2018 examined the effectiveness of a placemat intervention promoting healthy “Kids’ Meals of the Day” (defined according to the KLW standards) at a regional US quick-service restaurant. Fifty-eight families were randomly assigned to visit the restaurant either during an intervention period or a control period. Those allocated to the intervention period received the placemat as they entered the restaurant. While more children in the intervention group (21%) ordered a healthy main or side dish compared to controls (7%; p = 0.03), these differences were driven mostly by the selection of healthier side dishes. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups in the selection of healthier main meals (17.9% of children in the intervention group ordered a healthy main vs. 6.7% of controls (p = 0.19)) and no difference in ordering of healthy drinks between the intervention (28.8%) and control (30.0%) groups (p=0.90).

The main limitation with Anzman-Frasca et al., 2018 is that the study only assessed the effectiveness of the placemats in the short term. Children’s choices were assessed at only one dining occasion; the study design had no follow-up to assess the willingness of the restaurant chain to keep the placemats, and so no means of assessing the long-term sustainability of placemats as a promotional strategy.

Schneider et al., 2022 explored the impact of nudging and boosting elements on sales of a new healthier children’s meal at a full-service restaurant in Mannheim, Germany. Two menus were alternated in the restaurant between an intervention phase (when the intervention menu, containing nudging and boosting elements, was used) and a control phase (when the restaurant’s regular menu, which did not have the nudging and boosting elements, was used). Both the intervention and control menus contained the new, healthier children’s meal. The healthy children’s meal accounted for 4.2% of all orders during the intervention phase, and 4.4% of all orders during the control phase (p= 0.90). These findings show that nudging and boosting elements are not associated with significant changes in orders of healthier children’s meals.

The evidence presented in these 4 studies shows that signposting initiatives may be associated with healthier ordering habits by parents and children in the short term. However, there is limited evidence about the effectiveness of signposting initiatives in encouraging healthier ordering habits in the long term.

3.2.4. Incentives

Three studies were identified which examined the impact of incentives in encouraging parents and children to choose healthier restaurant meals. Two of these studies examined toy incentives (Downs & Demmler, 2020; Reimann & Lane, 2017) and one examined fundraising incentives (McNally et al., 2020).

Reimann & Lane, 2017 tested the effect of toy incentives on children’s fast food meal selections. 109 school children were randomised into 1 of 2 experimental conditions across 2 repeated trials. The two conditions were:

-

a toy paired with the regular-sized meal bundle condition, where participants were offered the choice between a regular-sized Happy Meal, including a toy, and a smaller-sized Happy Meal, excluding a toy.

-

a toy paired with the smaller-sized meal bundle condition, where, participants were offered the choice between a regular-sized Happy Meal, excluding a toy, and a smaller-sized Happy Meal, including a toy.

There was a significant positive direct effect of toy pairing on meal choice, with a greater proportion of children selecting the smaller-sized meal bundle when this meal was paired with a toy. This presents statistically significant evidence that children can be incentivised to choose a smaller meal bundle meal if a toy is offered, rather than a larger (i.e. regular sized) meal bundle without a toy.

The main limitation with Reimann & Lane, 2017 is that, while the research involved children selecting from meal bundles prepared in a restaurant, the process of meal selection did not actually take place in a restaurant. Meal bundles were prepared at a local McDonald’s and delivered to the school’s cafeteria where the children made their meal selections. The setting may have impacted on children’s choices.

These findings are corroborated by Downs & Demmler, 2020, in their rapid evidence review examining the impact of food environment interventions on the diets and nutrition outcomes of children. Downs and Demmler’s review identified three studies (conducted in North America) that examined the use of toys in restaurant meals to incentivise the selection of healthier meals. The study reported that all three studies concluded that providing toys with healthier meals, while limiting inclusion of toys with less healthy meals, increased healthy meal selection.

McNally et al., 2020 examined the impact of in-restaurant interventions aiming to promote healthy choices via fundraising incentives benefiting school wellness programmes and point-of-purchase nutrition promotion. The study was carried out in one restaurant location involving 81 families with children from 12 different schools. The schools were randomly assigned to one of two intervention periods:

-

Fundraising Incentive (FI) donated funds for visiting the study restaurant

-

Fundraising-Healthy Eating Incentive (F-HEI) included FI with additional funds given when selecting a healthier menu item.

There was no significant difference in orders of healthier menu items between intervention periods. Of the 141 items ordered by participants during the first intervention period, 15.6 % were healthier items and, of the 90 items ordered in the second intervention period, 21.1 % were healthier items. Based on this, the authors concluded that the additional fundraising incentive had limited impact on increasing orders of healthier children’s meals.

There are a number of limitations which may have impacted on this study. Firstly, the authors note that participation rates for both intervention periods were lower than anticipated. The experiment was also carried out without the authors knowing whether this fundraising initiative would be motivating to parents, which may have impacted on participation rates. Finally, as the incentive amounts were agreed with restaurant operators, the optimum incentive amount required to motivate parents to select healthier menu items was also unknown.

Evidence presented in these studies show that toy incentives are associated with selections of healthier restaurant meals by children. Evidence for the effectiveness of other incentives (specifically, fundraising initiatives) is limited.

3.2.5. Social marketing

Social marketing refers to the use of marketing concepts and techniques to influence social behaviours in a way that improves health and society. (Stead et al., 2007).

Two studies (Hennessy et al., 2023; Hogreve et al., 2021) were identified which examined the impacts of social marketing interventions on encouraging parents and children to order healthier restaurant meals.

Hennessy et al., 2023 examined the impact of a parent-focused social marketing campaign (“You’re the Mom” campaign), promoting healthy children’s meals, on calories ordered and consumed by children at fast food restaurants. 1,686 parents from Massachusetts, USA, were randomised into 6 intervention groups (819 parents) and 5 control groups (868 parents), across 11 fast food restaurant chains. Cross-sectional data were collected 8 weeks before the campaign and the last 4 weeks of the campaign plus 4 weeks post-campaign. No statistically significant differences were found in calories ordered between the control and the intervention groups, suggesting that the campaign was not effective at reducing calories ordered and consumed by children at fast food restaurants.

While Hennessy et al., 2023 had a strong study design (including a large sample size, randomisation into control and intervention groups), the study did not reach its target sample size at baseline. It is unclear whether the lack of statistical significance was due to the study’s inability to reach its desired baseline sample.

Hogreve et al., 2021 tested the effect of a social norm intervention in encouraging parents to order healthier side items for their children in a restaurant setting. An initial field study was conducted (involving 89 parents, at two restaurant settings) which used a survey to measure parents’ “social comparison orientation” (that is, the tendency of individuals to compare their behaviour and attitudes to others). A follow-up field study was then conducted (288 parents, at four restaurant settings) in which parents were exposed to a “descriptive social norm” about healthy eating for children (specifically, an excerpt from a newspaper article claiming that 75% of all parents choose healthy products for their children at fast food restaurants). Parents were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 experimental conditions: those who saw the new social norm information contained in the newspaper excerpt; and those who did not. Data from receipts were then used to record parents’ orders for their children. Results showed that 51.0% of parents who received the social norm information chose at least one side item perceived as healthy, compared to 39.4% of parents who did not receive the information (b = .27, Z = 4.53, p = .03).

Based on these findings, the authors conclude that parents with a high social composition orientation are more likely to order healthier side items for their children, when presented with information suggesting that other parents choose healthy meals at a fast-food restaurants.

One of the limitations of Hogreve et al., 2021 is that “healthy meals” or “healthy side items” are not clearly defined; the study is based more on participants’ perceptions of what constitutes a healthy side. Furthermore, the researchers also stated that interventions involving changing social norms are most effective for parents with high “social comparison orientation” (i.e., a high propensity for social comparison within their peer group). This suggests that changing the social norm may not encourage healthier ordering habits amongst all parents.

Evidence presented in the 2 studies about social marketing shows that social marketing is of limited effectiveness at encouraging parents to order healthier restaurant meals for their children.

3.3. Objective 3: Motivators and barriers influencing food business participation in initiatives to improve nutritional content of children’s meals

Four studies were identified which explicitly discuss motivators and barriers to restaurants participating in children’s menu reformulation initiatives (Anzman-Frasca et al., 2017; Ayala et al., 2016; Karpyn et al., 2020; Redelfs et al., 2021).

Information on motivators and barriers was also found in a further 5 studies (Crixell et al., 2014; Harpainter et al., 2020; Lopez et al., 2017; Peters et al., 2016; Ritchie et al., 2022). While these studies focus on initiatives to promote children’s menu reformulation (objective 1) or encourage behaviour change by parents and children (objective 2), they also offer relevant information which adds to the evidence base for objective 3.

3.3.1. Motivators

An interest in providing healthier menu items for children

Evidence from 3 studies (Anzman-Frasca et al., 2017; Ayala et al., 2016; Redelfs et al., 2021) suggests that a manager or owner’s interest in promoting children’s health is a motivating factor for some food businesses to participate in initiatives to improve nutritional content of children’s meals.

According to Ayala et al., 2016, an interest in providing healthier meals for children was one of the reasons given by restaurants who agreed to participate in the US Kids Choice Restaurant Programme (KCRP). Similarly, Redelfs et al., 2021 found that an owner’s interest in health was cited as one of the facilitators which encouraged restaurants to participate in the Eat Well El Paso! (EWEP) project in Texas.

Anzman-Frasca et al., 2017 conducted qualitative research with 4 US restaurant executives exploring perspectives on supplying healthier children’s meals. Restaurant managers mentioned corporate social responsibility as a potential driver for reformulating children’s menus to be healthier.

The main limitation of the studies cited above is that they are all based on small sample sizes (8 restaurants who agreed to participate in the KCRP; 22 restaurants involved in EWEP who agreed to interview; 4 restaurant executives interviewed by Anzman-Frasca et al.), meaning that results aren’t fully representative of the broader restaurant industry. It is also unclear what proportion of restaurant owners interviewed mentioned interest in health as a motivator to participation.

Evidence suggests that more restaurant managers may support healthier children’s menus if the value of policies and initiatives to improve the nutritional quality of children’s meals is explained to them. Karpyn et al., 2020 interviewed 50 managers of restaurants in Delaware about their knowledge and perceptions of the State of Delaware’s healthy default drink (HDD) act. Although only a small proportion of managers (6%) had heard of the policy, when the policy was explained to managers, the majority (75.5%) were in support, with only one manager opposed to the policy. When asked what they considered to be the benefits of the policy, most managers saw the policy’s benefits as helping the restaurant to play a role in supporting children’s health.

Similar findings are also reported with the implementation of HDD policies in California and Wilmington (Ritchie et al., 2022). Although most managers in California (60% of 75 managers interviewed) and Wilmington (93% of 15 managers interviewed) had not heard of their jurisdiction’s HDD policies, after the policy was explained, most strongly (48.0% in California, 80.0% in Wilmington) or somewhat (17.3% in California, 20.0% in Wilmington) supported the policy.

Financial incentives

Two studies (Ayala et al., 2016; Redelfs et al., 2021) mentioned financial incentives as a factor that encourages restaurants to improve the nutritional quality of children’s meals.

Ayala et al., 2016 reported that restaurants were given $300 for participating in the KCRP. The manager or owner also received $40 for the two interviews they completed and waiting staff were given $10 per shift for allowing KCRP evaluation staff to observe them. Redelfs et al., 2021 also mentioned financial incentives as part of the EWEP project. This project benefited from 100% grant funding from the El Paso city Department of Public Health, to support participating restaurants in the development of healthier children’s menu items. The financial support from the funding was seen as a key factor encouraging participation in the project.

However, the evidence also suggests that financial incentives can be problematic. While the offer of funding or incentives may entice participation, time-limited funding can discourage restaurants from sustaining changes made through the initiative. Redelfs et al., 2021, in their evaluation of EWEP project, noted that the 100% grant funding model undermined long-term sustainability. Once the funding ended, most (16) of the 21 participating restaurants discontinued the healthier menu items. Only five restaurants still included the healthier items on their menus a year after the funding ended.

These findings suggest that while financial incentives, in the form of grant funding or monetary rewards for participation, may drive short-term participation, their longer-term impact is yet to be determined.

Collaborative approaches and rapport building

The 2 community-based interventions (Crixell et al., 2014; Redelfs et al., 2021) offer valuable insights on engaging restaurant owners and securing participation in children’s menu reformulation initiatives.

The Best Food for Families, Infants, and Toddlers (Best Food FITS) community intervention, reported by Crixell et al., 2014, highlighted the importance of building relationships with local restaurant owners to make children’s menus healthier. As part of the recruitment process for the Best Food FITS intervention, research teams found that visiting restaurants and engaging with owners helped to establish a rapport and build relationships, which contributed to the successful recruitment of the 17 restaurants. The Best Food FITS community intervention also highlighted the importance of collaborative approaches. Owners appeared more willing to make changes to their children’s menus if new menus incorporated old menu items. (Crixell et al., 2014). Using existing menus as a basis for new ones offers continuity, minimises perceived disruption and maintains cost neutrality by making use of items which the restaurant may already have in stock.

Redelfs et al., 2021 found that the EWEP project was also underpinned by a collaborative approach. The EWEP project team (which included registered dietitians) worked closely with the owners, managers and chefs of participating restaurants to help them to create new or modified adults’ and children’s menu items which met nutritional standards developed specifically for the project by the dietitians.

However, this collaborative approach has disadvantages; it is time and resource intensive, requiring researchers to build relations with restaurants over a long period leading up to interventions. It works best with independently owned restaurants or those with owner-managers who control their menus, while corporately owned chains appeared harder to engage with (see section 3.3.2 for more discussion of corporate policy as a barrier).

3.3.2. Barriers

Corporate policy

Evidence from 5 studies (Crixell et al., 2014; Harpainter et al., 2020; Lopez et al., 2017; Redelfs et al., 2021; Ritchie et al., 2022) suggests that corporately owned chain restaurants are particularly difficult to both engage with and recruit.

Corporate policy was cited as a reason for declined participation by 65 of the 135 restaurants approached for the Best Food FITS community intervention. Only one of the 17 participating restaurants was a chain restaurant (Crixell et al., 2014). Corporate policy was also described as a barrier to participation by restaurants who were approached to take part in the EWEP project in Texas. (Redelfs et al., 2021). Similarly, corporate policy has also been noted as a barrier to restaurants adopting voluntary HDD standards for children’s meals (Harpainter et al., 2020), and to the implementation of the mandatory HDD act by restaurant owners in California (Ritchie et al., 2022).

Lopez et al.'s (2017) pilot feasibility study, which tested the efficacy of different signposting initiatives to promote healthier children’s meals at 4 US chain restaurants, also found evidence of similar barriers. While the chains in question consented to the study taking place, Lopez et al. noted that corporate policy often impacted on serving staff compliance with the intervention, especially in the fast-food restaurants. While participating restaurants agreed to limit additional promotions during the 8 week intervention period, serving staff at the fast-food restaurants were asked to prioritise a competing national promotion. This led to fewer verbal prompts for the healthier, Kids Live Well (KLW) menu items, which impacted on the promotion and sales of healthier children’s meals. (Lopez et al., 2017).

There were also several issues noted around the willingness of the chain restaurants in question to implement the signposting initiatives:

-

Placemats promoting the healthier, KLW meals were not consistently distributed to families, especially in the fast-food restaurants.

-

Restaurants failed to indicate on their menus and menu boards which of their kids’ meals qualified for KLW.

-

The sign promoting the KLW meals was smaller than other promotional signage in the restaurants.

-

Few families reported that they received prompts from servers to purchase the KLW meals that came with the free promotional toy (Lopez et al., 2017).

However, such tactics are not unique to chain restaurants. One of the independent restaurants that participated in the KCRP initiative also refused to put promotional materials in restaurants (Ayala et al., 2017).

This evidence suggests that corporate-level directives can severely restrict the ability of individual chain restaurants both to participate in and comply with children’s menu reformulation initiatives.

Limited customer demand for healthier children’s meals

Evidence from 3 studies (Anzman-Frasca et al., 2017; Peters et al., 2016; Ritchie et al., 2022) reveals a perception amongst restaurant owners that there is limited customer demand for healthier children’s meal options.

According to qualitative research undertaken by Anzman-Frasca et al., 2017, with 4 restaurant executives in the USA, executives explained that healthier children’s meals are not customers’ preferred ones. This is linked, in part, to customer habits and preferences, but also the fact that, in the opinion of restaurant owners, children are more exposed to less healthy foods. (Anzman-Frasca et al., 2017).

Evidence also suggests that customer preference may act as a barrier to the implementation of healthier default options on children’s menus. Peters et al., 2016 described acceptance levels of healthy defaults by consumers as a challenge to the implementation of optimal defaults. However, the acceptability of healthier defaults to parents and children did not impact on sales, with broadly positive findings reported (healthy default drinks were included in 66.3% of all orders, over the study period, while healthy default sides were accepted in 47.9% of all orders.)

Customer preferences have also been described as a barrier to the effective implementation of HDD acts in the USA. According to Ritchie et al., 2022, when the 22 California restaurant managers who were aware of HDD policy were asked what made implementation of the policy difficult, the most common response was customer preferences.

Perception that restaurants are not responsible for customers’ choices

Evidence from one study (Ayala et al., 2016) suggests some restaurant owners may perceive that it is not the responsibility of restaurants to tell customers how to eat healthier.

Ayala et al., 2016 found that, of the 41 San Diego restaurants initially approached to take part in the KCRP, 18 restaurants refused. One of the reasons given was that managers and owners did not want to change their menus or tell customers how to eat. This attitude alludes to a perception amongst some restaurant owners that responsibility for healthy eating choices lies solely with the consumer, and that restaurants have limited responsibility in guiding the choices of customers.

However, this attitude was only mentioned in one study included in this review, and Ayala et al. do not specify how many restaurant owners expressed this attitude. This attitude could, therefore, be a minority view.

Limited awareness of reformulation legislation

Evidence from 2 studies (Karpyn et al., 2020; Ritchie et al., 2022) shows that a lack of awareness of children’s meal reformulation laws, on the part of restaurant managers and owners, is a barrier.

Karpyn et al., 2020, in their qualitative study of restaurant manager’s perceptions of Delaware’s HDD act, found that, prior to the implementation date, only 3 of the 50 managers interviewed (6%) had heard of the policy. Similar findings were also reported by Ritchie et al., 2022, in their study of HDD policies in California and Wilmington. After HDD policies were implemented, the majority of the 75 managers interviewed in California (60%), and the 15 managers interviewed in Wilmington (93.3%), had never heard of the policy. In California, 20% of managers said they knew “a little about” the policy, while only 9.3% reported knowing a lot. None of the 15 managers in Wilmington knew about the policy and only one had heard of it.

The main limitation with the study by Karpyn et al., 2020 is that managers were interviewed after the HDD policy was passed but before the policy came into effect. More managers might have been aware of the policy if they had been interviewed after the law was enforced. Nonetheless, the findings highlight the lack of understanding of the policy by restaurant managers, in the months between the law’s passage and its implementation.

The nature of how restaurants develop children’s menus

Evidence presented in 2 studies (Anzman-Frasca et al., 2017; Crixell et al., 2014) suggests that the way restaurant owners approach the development of children’s menu items may act as a barrier to reformulation.

Anzman-Frasca et al., 2017, in their qualitative research with 4 restaurant executives in USA, found that restaurant owners are often reluctant to make changes to children’s menus as children’s menu items tend to be quite fixed (more so than adults’ menu items). Executives reported that children’s meals are typically developed out of what is already available in the kitchen. They also explained that there is little incentive to invest in reformulating children’s menus, as children’s meals are not a main driver of restaurant profits. (Anzman-Frasca et al., 2017).

Issues around stocking may also act as a barrier to improving the nutritional quality of children’s menus. As part of the Best Food FITS programme, of the 61 restaurant owners and managers who provided feedback, 15% stated that they did not stock fruits and vegetables. This acts as a considerable barrier to menu reformulation. (Crixell et al., 2014).

Perception that involvement in reformulation initiatives would be time and resource heavy

Evidence from 2 studies (Ayala et al., 2016; Redelfs et al., 2021) reveals a perception among restaurant owners that involvement in children’s menu reformulation programmes would be time and resource-heavy and burdensome for management.

Some reasons given by the 18 San Diego restaurants that declined to participate in the KCRP included managers and owners being too busy. Another reason was that the intervention would have required more extensive management involvement than could be offered, especially during peak tourist season. (Ayala et al., 2016). These statements suggest a perception that participation in initiatives to make children’s menu items healthier requires a time commitment on the part of the manager that the restaurant is not able to sustain.

Similarly, the time-consuming nature of recruitment, as well as restaurant culture and a high turnover of staff, are all cited as barriers to participation by restaurants who were approached to take part in the EWEP project in Texas (Redelfs et al., 2021).

3.4. Objective 4: Impact of restaurant initiatives on profitability and food waste

Limited direct evidence relating to objective 4, impacts of restaurant initiatives on profitability and food waste, was found. Five studies were identified which made references to the impacts of healthier children’s menus on restaurant profits (Anzman-Frasca, Mueller, Lynskey, et al., 2015; Anzman-Frasca, Mueller, Sliwa, et al., 2015; Crixell et al., 2014; Karpyn et al., 2020; Ritchie et al., 2022). No studies were identified which examined impacts on food waste.

3.4.1. Impacts of healthy default drink policies on restaurant profits

Three studies were identified which referenced the impacts of healthy default drink (HDD) policies on restaurant profits (Crixell et al., 2014; Karpyn et al., 2020; Ritchie et al., 2022).

Crixell et al., 2014, in their study of the Best Food for Families, Infants, and Toddlers (Best Food FITS) community intervention, found that one third of the 61 restaurant managers interviewed agreed that sugar-sweetened drinks were the most profitable item on the menu. Feedback from managers and owners also revealed that sugar-sweetened drinks are important drivers of profits for some restaurants, and that removal of these items from the menu would cause financial challenges.

Karpyn et al., 2020 interviewed 50 managers of restaurants in Delaware about their knowledge and perceptions of the State of Delaware’s HDD act. Researchers asked managers about potential benefits of the policy, to which respondents reported drawbacks with most sharing concerns about lost sales and about milk. For example, one manager reported that the policy impacts negatively on restaurant sales. However, the researchers reported that, in structured interviews, managers were receptive to the HDD policy, despite having concerns about stocking and sales.

Ritchie et al., 2022, in their study of HDD act implementation in California and Wilmington, found that costs were not considered a challenge. When the 22 managers in California who were aware of the policy were asked what made policy implementation difficult, only one mentioned beverage costs as a challenge. In addition, the study found no significant pre- to post-policy changes in the weekly number of children’s meals sold, as well as no significant changes reported by managers in the percentage of children’s meals sold with water, milk, juice or sugar-sweetened drinks.

Evidence presented in these 3 studies reveals a perception among some restaurant managers that policies targeting sugar-sweetened drinks may impact on restaurant profits and sales.

3.4.2. Impact of healthier children’s menus on restaurant revenues

Three studies explored the impacts of implementing healthier children’s menus on restaurant revenues and meal prices (Anzman-Frasca, Mueller, Lynskey, et al., 2015; Anzman-Frasca, Mueller, Sliwa, et al., 2015; Crixell et al., 2014).

Anzman-Frasca, Mueller, Sliwa, et al., 2015 examined changes in children’s meal orders and restaurant revenue at 13 outlets of a regional US full-service restaurant chain, following implementation of a healthier children’s menu, which was compliant with National Restaurant Association’s Kids Live Well (KLW) standards. After the healthier menu was introduced, prices of children’s meals increased by $0.79 for breakfast meals and $0.19 for non-breakfast meals. Overall, restaurant revenue also continued to grow after implementation of the new menu in April 2012 (yearly percent change are as follows: 2008-2009: +1.5%, 2009-2010: −2.1%, 2010-2011: +11.1%, 2011-2012: +5.1%, and 2012-2013: +5.1%.)

In a follow-up study, Anzman-Frasca, Mueller, Lynskey, et al., 2015 analysed children’s meal orders and revenue at the same restaurant chain at one and two-year follow up periods. Findings reveal that orders of healthier children’s main meals were sustained over the study period. Based on this, the researchers concluded that the new, healthier children’s menu was both sustainable and financially viable for the restaurant. Total annual revenue across all 13 locations also grew by 5.31% from 2013 to 2014. This exceeded the average revenue growth in leading family dining chains at the time.

While these studies show that the implementation of healthier menus did not negatively impact on restaurant profits and revenues, growth in revenues cannot be attributed to sales of healthy children’s meals alone. Revenue calculations in these studies were based on sales of all children’s meals, not just the new healthier meals, meaning that growth in profits may have been driven by increases in sales of less healthy children’s menu items. It is also possible that healthier children’s menus may be more expensive, but that the costs may have been passed onto the consumer.

Crixell et al., 2014, in their study of the Best Food FITS community intervention, found that the average price of healthier children’s meals was not significantly higher than meals on pre-intervention menus. Crixell at al. also reported similar findings from an earlier piece research, which found that healthier children’s mains in full-service chain restaurants in Little Rock, Arkansas, were not more expensive than less healthy options.

Evidence from these 3 studies shows that the implementation of healthier children’s menus is not associated with declines in restaurant profits or substantial increases in menu item prices.

4. Discussion

Overall, findings from this literature review are mixed. There is limited evidence that voluntary community initiatives, involving collaboration between restaurant owners and an intervention team, may help independently owned restaurants improve the nutritional content of their children’s meals. In terms of influencing consumer behaviour, evidence suggests that healthier default options may encourage children and parents to select healthier meals in restaurants while toy incentives may encourage children to choose smaller, lower-calorie meals.

Mandatory legislation and voluntary nutritional standards were found to be of limited effectiveness at encouraging restaurants to make children’s menu offerings healthier.

All of the studies included in this review were conducted outside of NI and the UK. As a result, it is unknown whether the strategies identified as promising would be effective in improving children’s menu offerings within the specific cultural, policy, and food environment of NI.

For objective 1, studies of community initiatives reported some limited evidence of success in encouraging independently owned restaurants to improve the nutritional content of their children’s meals. These studies found that direct engagement, relationship building and close collaboration between restaurant owners and intervention teams were critical to ensuring restaurant buy-in and support for voluntary children’s menu reformulation initiatives. In particular, collaboration with restaurant owners on menu design, using items already included on restaurants’ existing menus, was found to be an important factor in encouraging restaurants to participate. However, community initiatives tend to be resource intensive, small in scale, and the changes may not be long term as businesses may drop out.