AMR terminology

In developed countries, so-called epidemiological cut-off values (ECOFFs) have been used to determine ‘resistance’ to antibiotics, but it should be noted that ECOFFs do not necessarily indicate clinical resistance. ECOFFs distinguish between individuals within a species which have or have not developed any phenotypically detectable acquired resistance. The ECOFF is the upper end of the wild type of the species for the agent and does not necessarily indicate clinical resistance. The Advisory Committee on Microbiological Safety of Food (ACMSF) Working Group on Antimicrobial Resistance has published recommendations on the use of AMR terminology/nomenclature used in FSA reports which includes how best to integrate ECOFFs, clinical breakpoint and genomic data to most accurately reflect the AMR status of bacterial isolates found in food surveys. Results in this study where we have assigned ‘resistance’ are based on ECOFFs.

Lay summary

In recent years, raw pet food (RPF) has become more popular among pet owners in the UK. RPF contains meats and other ingredients which are not cooked. This means that the final product may be contaminated with microorganisms including bacteria and viruses that make people ill (pathogenic ones) and some bacteria may be resistant (antimicrobial resistant (AMR) bacteria that could make it more difficult to treat an infection). This poses a risk that people could be exposed to harmful bacteria through contact with these foodstuffs or via infected pets. For example, as RPF products are defrosted and are handled at home, where good hygiene practices are not in place cross-contamination may occur to food intended for human consumption. There is also a risk that pets can spread pathogens and AMR bacteria if they have become infected themselves after eating RPF. AMR can potentially make treatment of bacterial infections by certain drugs ineffective thereby posing a risk to public health. This survey was carried out to determine what pathogens and AMR bacteria were present in raw dog and cat food on retail sale in the UK. A total of 380 RPF samples (277 raw dog food and 103 raw cat food) were obtained from retail stores and online purchases within the UK between March 2023 and February 2024.

The survey found that:

-

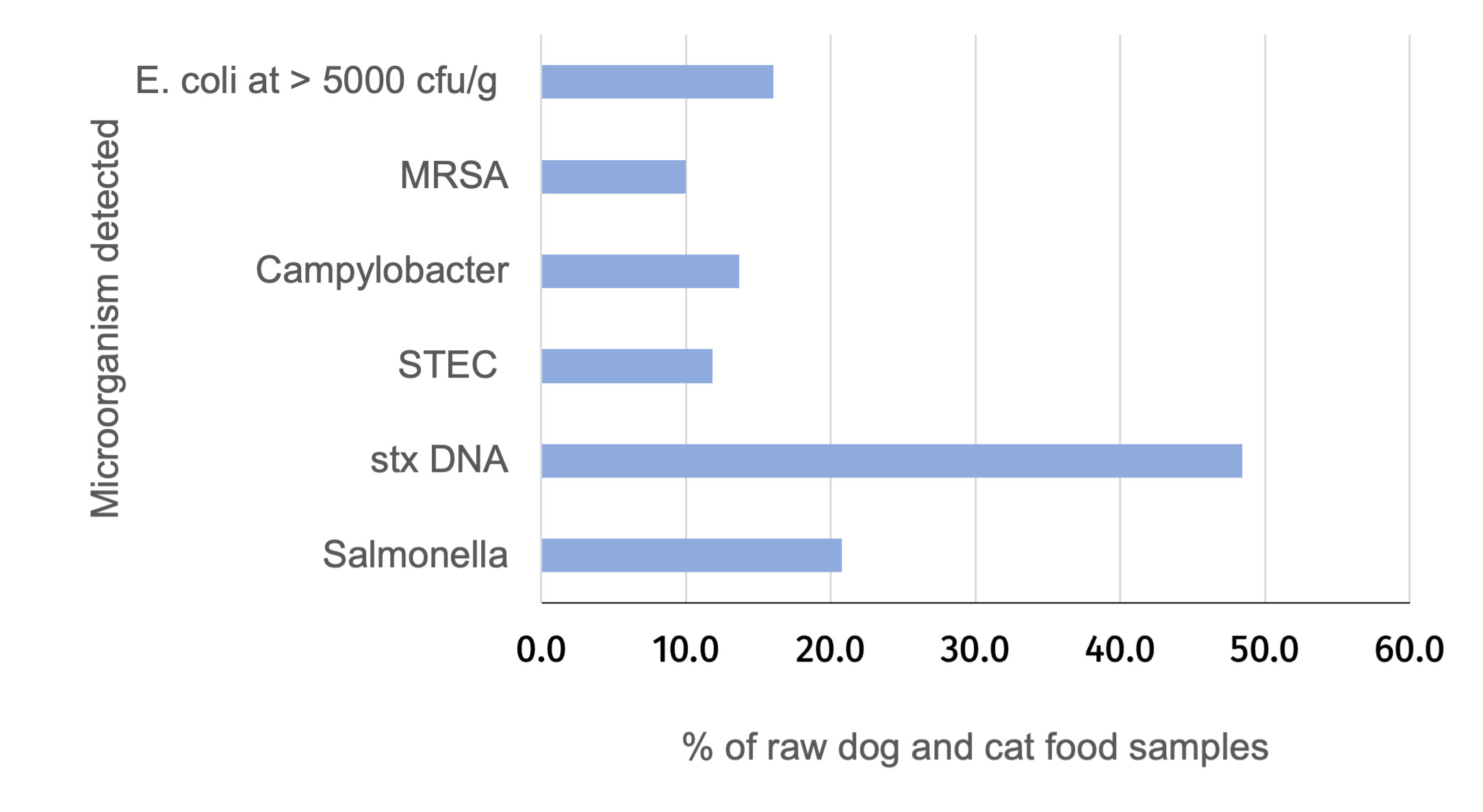

Pathogenic bacteria were detected in 35% of the RPF samples. This included Salmonella (in 21% of samples), Campylobacter (in 14% of samples) and Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) (in 12% of samples) with some of these samples contaminated by more than one of these pathogens.

-

Around 29% of the RPF failed to comply with what is allowed in UK legislation (due to detection of Salmonella and/or more than 5000 E. coli per g; 16.1% of samples had > 5000 E. coli per g)

-

AMR bacteria (defined using ECOFF thresholds) were detected in the RPF samples. E. coli with resistance to penicillins and other antibiotics were detected in 20% of all samples.

-

E. coli with resistance to the antibiotic colistin were detected in 1% of samples. Resistance to carbapenem antibiotics was not detected (both colistin and carbapenems are known as last resort antibiotics used in human treatment).

-

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) was detected in just under 10% of RPF samples.

-

Around 8% of the RPF samples leaked through the packaging during the thawing process. Despite this, contamination on the external packaging of the RPF samples was low; 1% of external surface of packs had Salmonella or Campylobacter; 1% of external surface of packs had more than 5,000 E. coli bacteria.

-

It is important for people to follow FSA’s advice on how to store, defrost and handle these products at home - especially if someone with a weakened immune system might be exposed. This will help minimise cross-contamination and lowers the risk of getting sick.

-

These findings show that RPF products carry a risk to human health and it is important that pet owners are aware of this to take appropriate measures to reduce risk to themselves and their pets.

Executive summary

The extensive use of antimicrobials in humans and animals has been a significant natural driving force in AMR development. The development of multi-drug resistant (MDR) bacteria has been described as the ‘silent pandemic’ with infections in humans and animals caused by MDR organisms associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. Raw pet food (RPF) has become more popular in recent years among pet owners in the UK as well as other developed countries. RPF products do not undergo any heat treatment to eliminate AMR and pathogenic bacteria during the production process. This creates a risk of such products being contaminated with both pathogens (including those pathogenic to humans) and AMR bacteria and these products may be available to the general public at UK retail sale.

The study has assessed the occurrence of such bacterial hazards from raw dog and cat food on retail sale in the UK. The presence of Salmonella spp., Campylobacter spp., Shiga-toxin producing E. coli (STEC), methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and E. coli including those with extended-spectrum beta lactamase (ESBL) and/or AmpC-phenotypes or with resistance to carbapenems and colistin was investigated. Recognised standard methods were used and epidemiological cut-off values (ECOFFs) were used to assign phenotypic resistance to antimicrobials.

A total of 277 raw dog and 103 raw cat foods (covering 50 brands) were sampled at retail sale across the UK, including online purchases, between March 2023 and February 2024. This survey found that:

-

Salmonella was detected in 20.8% of RPF samples at an average level of 1.0 MPN/g and, included 24 different serovars. Salmonella was detected in at least one sample from 28 of the brands tested. MDR Salmonella isolates were detected in 8.9% of samples and one Salmonella Infantis was ESBL-producing.

-

Campylobacter was detected in 13.7% of samples and in 3.3% between 10 and 130 CFU/g of campylobacters were detected. C. jejuni and C. coli were present in 28 samples each. MDR was detected in 21.4% of C. jejuni and in 11.5% of C. coli but no isolates were resistant to erythromycin or gentamicin. Whole genome sequencing (WGS) of 44 Campylobacter isolates revealed 29 different sequence types and genetic determinants for AMR agreed with results obtained from phenotypic testing.

-

STEC was detected in 11.8% of samples and PCR-based testing detected stx DNA in 48.4% of samples. Two of 44 STEC isolates were predicted to be MDR from analysis of whole genome sequencing (WGS) data.

-

MRSA isolates that tested positive for the mecA gene were detected in 9.5% of samples and included five sequence types (STs) with the livestock associated (LA) ST398 being most common. No MRSA were resistant to vancomycin or linezolid.

-

More than 5000 CFU of indicator E. coli per g was detected in 16.1% of samples.

-

The percentage of samples with E. coli with an ESBL-producing or AmpC-producing or both ESBL- and AmpC-producing E. coli (hereafter referred to as ESBL-/AmpC-producing E. coli) was 19.6%. E. coli with resistance to colistin (these had MIC = 4 mg/l) and harbouring the mcr-1 gene was detected in 1.3% of samples. No E. coli with resistance to carbapenems were detected.

-

In 109 (28.7%) samples the statutory criteria (requiring absence of Salmonella and counts of Enterobacteriaceae to be ≤ 5000 CFU/g) were exceeded (as E. coli counts of > 5000 CFU/g would also result in a count of Enterobacteriaceae of >5000 CFU/g as all E. coli are within the Enterobacteriaceae family of bacteria).

-

Salmonella and Campylobacter were detected in one sample each of 189 outer packaging samples. Two outer packaging samples had > 5000 CFU of E. coli per sample. An AmpC-producing E. coli was detected in one of 88 outer packaging samples tested for ESBL-/AmpC-producing E. coli, but E. coli with resistance to colistin or carbapenems were not detected in any of the outer packaging samples.

It is important that consumers follow FSA’s guidance around storing, defrosting and handling these products within the home as these will minimise cross-contamination events from occurring and thereby reduce the risk to consumers. Providing clear advice to the public as well as any catering establishments on the risks posed by RPF products can support pet owners to take appropriate measures to reduce risk to both themselves and their pets.

1. Introduction

One of the core missions within the FSA’s Strategy for 2022-2027 is to ensure that ‘food is safe’. A key component of the work is to monitor pathogenic microbiological hazards, including those that are antimicrobial resistant, in retail foods. Surveys can provide a snapshot of the level of pathogens and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) contamination, and they are important in assessing potential consumer exposure to these hazards. Raw pet food (RPF) has become increasingly popular in recent years among pet owners in many developed countries, driven by non-specialist publications from the 2000s which promoted the use of RPF as a more ‘natural’ diet for dogs and cats (Freeman & Michel, 2001). Figures collated by UK Pet Food (previously the UK Pet Food Manufacturer’s Association (PFMA)) indicate that the size of the UK RPF market has grown significantly over recent years and is now estimated to be worth more than £130 million, within a total UK pet food market of £3.8 billion in 2023 (UK Pet Food, 2017; UK Pet Industry Statistics, n.d.).

RPF usually contain Category 3 animal by-products (ABP) that have been passed fit for human consumption in a slaughterhouse but are either surplus to human consumption needs or are not often consumed by people in the UK, including tripe, kidneys and bones. Any premises that handle or use ABP as part of their operation (hereafter referred to as ABP plants) must be approved with the Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA) according to assimilated Regulation (EC) No 1069/2009 (Regulation (EC) No 1069/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council, 2009). Raw pet food (RPF) must be packaged in clean leak-proof packaging and producers must give guidance on safe handling, storage, and use of the product either by publishing guidance on their website or on the packaging. The Category 3 ABP used in RPFs have not undergone any preserving process other than chilling or freezing, as defined in assimilated Commission Regulation (EU) No. 142/2011 (Commission Regulation (EU) No 142/2011 of 25 February 2011 implementing Regulation (EC) No 1069/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council laying down health rules as regards animal by-products and derived products not intended for human consumption).

RPF does not undergo any heat treatment, which would have the potential for eliminating bacterial pathogens, as it is defined as pet food that is made up of unprocessed or uncooked meat, offal and raw bone. Any contamination including bacterial pathogens and AMR would not be eliminated from the final retail raw pet food product. There are a wide range of RPF products available on the market, typically comprising muscle meat (and small fragments of bone in some instances) from a wide range of animals (e.g. poultry, sheep, cattle, pigs, etc.) and abdominal organ content such as offal or tripe. RPFs may contain secondary ingredients including fruit, vegetables, grains, oils, and other nutrients (e.g., vitamins, minerals, etc.). Various content of animal origin, not typically popular at retail, may also be included in RPF (e.g., kangaroo, boar, venison, etc.). The vast majority of RPF products are sold frozen in pouches or tubs, vacuum-packs, or sausage-shaped tubes (chubs) and can vary in size from single meals (typically 500 g) to bulk packs weighing several kilograms. Frozen raw pet food products typically have a durability date (usually a best before date) of more than one year and may be stored in domestic environments alongside frozen food intended for human consumption. When frozen meat and RPF is defrosted there is an opportunity for multiplication of bacteria, including those that are pathogenic, particularly if the product is left to defrost at room temperature for a prolonged period. The labelling requirements under both the ABP and Marketing and Use Regulations do not specifically require safe handling instructions, so it is unclear how these products are being defrosted or stored after defrosting.

There is growing evidence that raw dog and cat foods can contain a higher prevalence of pathogens and AMR bacteria compared to meat for human consumption, and therefore is a potentially a riskier route by which consumers could be exposed to microbiological hazards either as a result of poor handling practices within the home or via a zoonotic route (Dhakal et al., 2024). The integrity of the packaging of samples may be compromised during thawing leading to leakage of microbiologically contaminated fluid from these products (Morgan et al., 2022). Microbiological incident notifications associated with RPF increased from one reported in 2015 to eleven in 2017 and eight in first quarter of 2018 (Advisory Commitee on the Microbiological Safety of Food (ACMSF), 2018). Unpublished data from the FSA suggests that these notifications have continued to increase since 2018 with 19 reported in 2024 (peaking at 24 in 2021). Raw meat diets have been shown to harbour pathogenic and zoonotic bacteria including Salmonella spp., Campylobacter spp., STEC, Listeria spp. and Clostridium perfringens (Hellgren et al., 2019; Kaindama et al., 2021; Nemser et al., 2014; Nilsson, 2015; Strohmeyer et al., 2006; van Bree et al., 2018; Weese et al., 2005). Most recently avian flu has been reported in the USA to transmit via diets containing raw poultry to cats causing serious infections in these FDA Outlines Ways to Reduce Risk of HPAI in Cats | FDA. AMR bacteria such as extended-spectrum beta lactamase (ESBL-) producing E. coli have also been detected in RPF (Morgan et al., 2022; T. A. Nüesch-Inderbinen et al., 2019; van Bree et al., 2018). Moreover, dogs fed a raw meat diet had a higher percentage of ESBL-positive samples compared to dogs fed a non-raw meat diet (Morgan, Pinchbeck, Haldenby, et al., 2024).

As part of the FSA’s feed delivery sampling programme for 2020/21, Local Authorities in England sampled RPF and found Salmonella contamination in 12% of samples, whilst two thirds of the samples examined contained Enterobacteriaceae levels of >5,000 CFU/g (FSA, Unpublished). Such samples were non-compliant with assimilated Commission Regulation (EU) No. 142/2011 that states Salmonella should be absent and sets an upper limit of 5,000 CFU/g for Enterobacteriaceae. Some of these results have resulted in pet food needing to be recalled as the presence of Salmonella could potentially be harmful (see Natural Instinct recalls several products containing duck because salmonella has been found in the products | Food Standards Agency). It should be noted that all E. coli are in the Enterobacteriaceae family of bacteria and that any sample with > 5000 E. coli CFU/g would therefore be non-compliant.

Both Salmonella and Campylobacter are well recognised zoonotic pathogens and can cause clinical infection, such as diarrhoea, in dogs and cats, particularly in puppies and kittens. The risk of pets consuming previously frozen RPF contaminated with Campylobacter may be reduced as this pathogen is relatively sensitive to freezing. Testing for Campylobacter in studies of RPF outside the UK have reported varying prevalence and in some none were detected. To our knowledge no study prior to this one has been carried out to determine the presence of Campylobacter in UK retail RPF products.

Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) are a group of Gram-negative bacterial pathogens that can exist as part of the microbiota (usually as commensal organisms) in ruminant animals such as cattle and sheep, but can cause disease in humans. A wide range of animals can become colonised with STEC, transiently or not, including domestic pets, small mammals and birds, but ruminants are the main animal reservoir. Over 100 different STEC serotypes are associated with human illness and the burden associated with human infections is considerable (Majowicz et al., 2014). It is recognised that for many STEC incident investigations, it can be very challenging to confirm detection of STEC from food or environmental sources that may be implicated through epidemiological evidence. STEC can cause severe illness in humans, and it is possible that pets fed RPF products contaminated with STEC could act as asymptomatic carriers and shed STEC in their faeces (Bentancor et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2020; Treier et al., 2021). In dogs there is some evidence to suggest that STEC infection can potentially cause symptoms such as thrombocytopenia, haemolytic anaemia, and acute renal failure but diarrhoea may be absent (Do & Seo, 2024). To our knowledge there have been no studies prior to this one on the occurrence and types of STEC in RPF sold at retail in the UK.

MRSA emerged as a nosocomial pathogen but has since become an established community pathogen and, most recently, has found a new ecological niche in animals. MRSA is now widely distributed among food-producing animals, which are considered a reservoir for human MRSA infection (Lakhundi & Zhang, 2018). Cats and dogs can be colonised with MRSA in the mouth and/or nose, and both animal-to-human and human-to-animal transmission are considered possible (Harrison Ewan et al., 2014; Kaspar et al., 2018; Weese et al., 2006). MRSA can also cause infections in these animals (Weese et al., 2006). To our knowledge, occurrence of MRSA in raw pet food sold in the UK at retail has not been investigated previously.

E. coli are mainly found in the gut of warm-blooded animals (presenting as commensal bacteria) and often representing the most abundant facultative anaerobe of the human intestinal microbiota (Kaper et al., 2004). The presence of E. coli in food does not necessarily indicate a direct risk to health but can be indicative of faecal contamination, cross-contamination, poor hand/personal hygiene, poor cleaning, poor quality of materials, undercooking and/or poor temperature / time control. Elevated levels of E. coli in foods may help identify conditions leading to an increase in the risk of contamination with human pathogens (Ekici G, 2019). It is possible that pets fed RPF products contaminated with E. coli could become carriers and shed such E. coli including AMR E. coli in their faeces. In a study from Sweden (Runesvärd et al., 2020) E. coli was detected in faecal samples from dogs fed RPF. E. coli was recovered from a 6-week-old puppy that died of septic bacterial enterocolitis and had been fed raw cat food but it was unknown if the cat food was the source of infection (Jones et al., 2019).

The methodology used in this survey was based on current EU standard protocols for the testing as part of microbiological harmonised surveillance of raw meats e.g. beef, chicken and pork. The project tested samples for the presence of pathogens including Salmonella, Campylobacter, STEC and MRSA. These pathogens were also tested for AMR and analysis of whole genome sequencing (WGS) data provided the sequence type (ST) and identified genetic determinants for AMR. Examination of samples for AMR E. coli involved culture on agar media containing cephalosporin, colistin and carbapenem antimicrobials. E. coli isolates were screened against a panel of antimicrobials to determine their susceptibility to antimicrobials. The resultant pattern of resistance is characteristic of the beta-lactamase enzymes produced by the E. coli isolate, of which there are three main AMR phenotypes, AmpC, extended spectrum beta lactamase (ESBL) or carbapenemase-producers. ESBL and AmpC enzymes confer resistance to cephalosporins, whilst carbapenemase enzymes additionally confer resistance to the ‘last resort’ carbapenem antibiotics. E. coli isolates with resistance to colistin (an important drug in the treatment of highly resistant bacterial infections in humans) were screened for the presence of mcr resistance genes, which may be located on plasmids that can transfer amongst bacteria.

This study was initiated to gain a better understanding of the types and quantities of AMR bacteria and pathogens in raw dog and cat food on retail sale in the UK. Whilst pet foods are not consumed by the public, there are concerns around the storage and handling of such feed products within the home and the potential of cross-contamination of foods for human consumption and surfaces within domestic kitchens. Raw pet food products may also contain pathogens that could infect pets and even if asymptomatic could pose a zoonotic risk of infection in humans and this work aimed to further a better understanding of these risks.

2. Material and methods

The survey was based on the requirements of the FSA published tender FS900253 aiming to test raw dog and cat food samples from March 2023 to February 2024. During this time a range of raw dog and cat food products were collected across the UK. The raw dog and cat food samples were tested using internationally recognized standard methods, comprising detection of Salmonella spp. (Salmonella), Campylobacter spp. (Campylobacter), shiga-toxin producing E. coli (STEC), methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and E. coli including those with extended spectrum beta lactamase (ESBL) and/or AmpC β-lactamase enzymes, resistance to colistin or resistance to carbapenems.

2.1. Sampling design

The survey design, sampling and transportation of samples to the laboratory was undertaken by Hallmark Ltd in accordance with the FSA specification.

2.1.1. Number of samples and sampling period

The study aimed to collect 280 raw dog food samples and 100 raw cat food samples from retail outlets in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. Scotland was not included in the retail sampling regions, although some products tested may have been produced there. To strengthen robustness, an additional 5% contingency was added. Sampling was evenly distributed across a 12-month period (March 2023 to February 2024), ensuring temporal balance across four quarters.

2.1.2. Type of samples

Samples were limited to commercially available, packaged and labelled raw dog and cat food products that had not undergone any preservation processes beyond freezing (or chilling). This encompassed a range of predominantly meat-based products, both fresh and frozen, sourced from various retail outlets and online suppliers nationwide. Exclusions comprised dried, freeze-dried, cooked, or heat-treated variants, as well as other non-relevant raw pet food items such as whole cuts, treats, and vegetarian or fish-based products.

2.1.3. Market Share Data

Due to the absence of formal market share data for raw pet food, a “basket of typical products” approach was adopted. This is a recognised method in public health and economics, often used when robust sales data are unavailable. It involves compiling a curated list of representative products from known producers and assuming they broadly reflect the wider market. This method, while not as precise as market-share-weighted random sampling, enables practical and repeatable surveillance insights.

To construct this basket:

-

We conducted a systematic internet search to identify UK-based raw dog and cat food producers.

-

From this, we compiled a list of 38 eligible brands with labelled, packaged, meat-based products.

-

This list was reviewed and validated by the FSA.

-

Sampling ensured at least one product per brand across the year.

-

A proportional-to-size element was introduced to reflect the relative visibility of larger brands while maintaining representation of smaller producers.

-

Selection was randomised without replacement each quarter to avoid duplication.

-

Products with fish, vegetarian contents, or heat-treatment were excluded.

This basket ensured product and brand diversity and supported consistency over time

2.1.4. Sample region

Samples were collected across retail outlets in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, with Scotland excluded from retail sampling. However, some tested products originated from Scottish manufacturers. As specific pet population data were not available, we used human population size (Census-based NUTS2 regions) as a proxy for pet ownership density to guide regional allocation.

In addition to in-store purchases, online platforms were included to reflect modern consumer access to raw pet food, incorporating both region-specific and nationwide suppliers. Products were selected to avoid repeat purchases from the same batch, store, or supplier order, supporting sample diversity and integrity.

Although online accessibility may reduce the significance of physical region, maintaining geographical stratification ensured coverage of suppliers serving different consumer bases and mitigated location-related variation in handling or storage practices.

2.1.5. Selection of samples for packaging testing

Following FSA specifications, outer packaging of 189 samples was swabbed for bacterial and AMR testing. A systematic method was used where every other dog and cat sample was selected—ensuring a 50:50 distribution between species. Selected samples were marked with a “P” prefix in all documentation and within the HallMark Sampling System to guide the laboratory.

2.1.6. Data recording

All sample data were recorded using the HallMark Sampling System (HMX), a secure, cloud-based platform that supports real-time tracking and reporting. For every sampled product, surveyors logged a comprehensive set of data fields, including:

-

Unique sample number

-

Purchase date and location (NUTS2 region)

-

Retailer or online supplier details

-

Product description and brand name

-

Main and secondary protein types

-

Storage format (chilled/frozen)

-

Durability date (use by or best before)

-

ABP approval codes and origin information

-

Packaging type and integrity

-

Temperature status at dispatch

-

Any food safety labelling or warnings

Photographs of each product—including front, back, and any peel/reveal labelling—were captured at the point of packing and uploaded to the HMX platform. These images ensured visual validation of key details such as ingredient lists, durability dates, and ABP approval codes, and were linked to the corresponding sample ID to enable full traceability.

This detailed dataset enabled efficient verification by the laboratories, supported quality control checks, and ensured compliance with the FSA’s data and documentation requirements.

2.1.7. Collection and transportation

HallMark was responsible for both sampling and transportation of raw pet food samples to the designated UKHSA laboratories. To uphold sample integrity and meet the FSA specification, we implemented detailed protocols covering sampling methodology, equipment use, packaging, labelling, and courier arrangements.

All samples were handled using tamperproof sampling kits provided centrally by HallMark. Each sample was individually sealed in a sterile grip-seal bag, then double-bagged in a numbered, tamper-evident outer sample bag with a unique identifier to ensure traceability and prevent cross-contamination. Digital photographs of each product were captured pre-dispatch, showing front, back, and label details, and uploaded to the secure HallMark Sampling System (HMX) to aid verification and traceability.

Samples were stored in insulated Icertech boxes with frozen chill packs, ensuring strict cold chain maintenance during transit. Ice packs were pre-frozen for at least 48 hours, and physical dividers or bubble wrap were used to prevent direct contact with the products. Packaging was sealed and clearly labelled “PERISHABLE.” Products were dispatched using tracked courier services Next Day by 10:30am to ensure timely delivery.

Retailers were notified of the sampling using FSA-approved correspondence. For large retailers and online suppliers, notifications were issued centrally. For small independent outlets, a hard-copy FSA leaflet was provided in-store post-purchase.

To avoid duplicate sampling and batch contamination:

-

Only one product per premises or online order was collected.

-

Each sample was packed individually and handled separately.

-

Surveyors followed strict protocols to avoid reusing equipment unless it had been disinfected.

Upon delivery to the lab, handover protocols were followed to confirm delivery, temperature status, and packaging integrity. Temperature readings were taken and recorded on arrival. Any deviations were reported by the laboratory to HallMark via the HMX system

2.2. Deviation from the sampling protocol

2.2.1. Number of samples

In total, 387 raw dog food and cat food samples were sampled. However, seven samples were not tested for the following reasons:

-

expired Best Before date

-

discarded because they were chilled instead of frozen

-

unsatisfactory temperature on arrival (including completely defrosted samples)

-

samples delivered after completing testing of 380 samples

A total of 277 raw dog food samples and 103 raw cat food samples were successfully tested, meeting the minimum requirements in the study design.

2.2.2. Chilled and frozen products deviations

According to the project specification, approximately 25% of raw pet food (RPF) samples were intended to be sourced as chilled products, with the remaining 75% as frozen. However, during the initial phase of sampling, HallMark identified significant challenges in sourcing chilled RPF products from the agreed list of eligible items.

Despite extensive efforts across multiple retail and online suppliers, chilled variants were largely unavailable on the UK market. Following consultation with the Food Standards Agency, it was formally agreed to proceed with sampling only frozen products.

This adjustment did not compromise the integrity of the study, as frozen formats are the predominant form in which raw pet food is sold and consumed in the UK. The revision ensured alignment with market conditions while maintaining the study’s overall robustness and relevance.

2.2.3. Durability date deviation

In accordance with the FSA project specification, it was necessary to record the durability date, either the “use by” or “best before” date, for each sample collected. However, 18 raw pet food samples did not display any durability date on their product labels at the time of sampling.

This deviation highlights a labelling non-compliance observed in a minority of products, where essential information regarding product durability was absent. Such inconsistencies in labelling practices may have implications for traceability and consumer safety, and were recorded in the sampling database for consideration by the FSA.

2.2.4. ABP approval codes

During the surveillance process, several discrepancies were observed between the ABP (Animal By-Product) approval codes listed on product labels and those found on the official list of approved pet food plants. These were not the result of data entry errors but were systematically recorded and passed to the Food Standards Agency for review. The observed discrepancies included:

-

Missing codes: In some cases, no ABP approval code was present on the product label despite the product being traceable to a known plant. Where possible, missing codes were inferred and documented in the results spreadsheet with accompanying comments.

-

Mismatched codes: In other cases, the ABP codes on packaging did not match those listed in the approved plant database. These discrepancies were flagged and annotated accordingly.

-

Unrecognised codes: Certain approval codes were present on packaging but could not be found on the official list of approved pet food plants. These instances were also noted and highlighted for FSA follow-up.

All such discrepancies were logged in the general comments section of the sampling database and included in the final dataset provided to the FSA.

After delivery to the laboratory, samples were thawed at fridge temperature (5 ± 1 °C) and processed while still cool to prevent bacterial growth prior to the microbiological tests being set up. Microbiological testing of samples was carried out as described below in UKHSA FWEMS laboratories that are 17025 accredited by UKAS.

2.3. Detection and enumeration of Salmonella, STEC and E. coli

2.3.1. Outer packaging swab

An outer packaging sample was collected using a SpongeSicleTM swab pre-wetted in 10 mL of minimum recovery diluent (MRD; composed of 1.0 g/L peptone and 8.5 g/L sodium chloride) and this was used to swab the entire outer packaging of the raw pet food sample. One mL of the MRD swab liquid was removed and used for E. coli enumeration (section 2.3.5), then 50 mL of buffered peptone water (BPW) was added, and 25 mL was used for the detection of Salmonella (section 2.3.3) and another 25 mL for detection of Campylobacter (section 2.4). The area of the packaging was measured (e.g. by measuring length and width) to allow calculation of total area swabbed.

2.3.2. RPF sample preparation and enrichment

A 1:9 homogenate of each raw dog or cat food sample was prepared by diluting a 27 g aliquot of sample in BPW, according to ISO 6887-1:2017 (International Organization for Standardization (ISO), 2017b). A portion of this homogenate (20 mL) was retained and used to enumerate E. coli (see section 2.2.4) and Campylobacter (see section 2.3). The remaining 250 mL of homogenate was incubated at 37 ± 1 °C for 18-22 hours and then sub-cultured for the detection of Salmonella, STEC, E. coli, ESBL and/or AmpC-producing E. coli, colistin and carbapenem resistant E. coli (sections 2.3.2 to 2.3.5). The detection limit for the enrichment methods had a theoretical potential to detect one Salmonella, Campylobacter, STEC, MRSA or E. coli of interest per 25 g of sample. The minimum detectable level of Campylobacter using the enumeration method was 10 CFU per g of sample.

2.3.3. Detection and enumeration of Salmonella

For the detection of Salmonella the method based on ISO 6579:1:2017 was followed (International Organization for Standardization (ISO), 2020). After enrichment in BPW, the sample homogenate was subcultured for secondary selective enrichment in Muller-Kauffman tetrathionate novobiocin (MKTTn) and Rappaport-Vassiliadis (RV) broths and incubated at 37 ± 1 °C for 24 ± 3 h and 41.5 ± 1°C for 24 ± 3 h respectively. Following incubation, a 50:50 mixture of MKTTn and RV was analysed by real-time PCR using the Salmonella species, Typhimurium and Enteritidis Multiplex PCR kit, following the manufacturer’s instructions (SureTect Salmonella species PCR Assay User Guide—AOAC/ISO 16140 (Pub. No. MAN0026138 L). Any samples with a positive PCR signal for Salmonella were subcultured onto xylose lysine deoxycholate and brilliant green agars for isolation. In addition, BrillianceTM Salmonella agar was used for samples with a high level of competing bacteria. Any isolations were confirmed using the Salmonella Multiplex PCR and/or biochemical tests. The outer packaging swab samples were processed in the same manner with the exception of Salmonella Multiplex PCR being carried out from the BPW enrichment broth.

Enumeration of Salmonella was conducted using a most probable number technique (MPN) as previously described (International Organization for Standardization (ISO), 2012a), although using larger test portions to increase sensitivity. Briefly, this involved testing 10 g, 1 g and 0.1 g portions of sample in triplicate or quintuplicate, and then followed by PCR and culture as described above. Only samples that were positive for Salmonella were enumerated. The MPN method had a theoretical limit of detection of one Salmonella in 30 g.

2.3.4. Detection of STEC

Detection of STEC followed the ISO/TS 13136:2012 method (International Organization for Standardization (ISO), 2012b). After incubation with BPW, an aliquot of the enrichment broth was subjected to real-time PCR for the stx gene using a SureTect™ Escherichia coli O157:H7 and STEC Screening PCR Assay (Thermofisher Scientific), performed according to the manufacturer’s instruction (Faulds et al., 2022), on a QuantStudio™ 5 Real-Time PCR instrument. Any samples positive for stx genes were followed up by culture using selective agars (cefixime tellurite sorbitol MacConkey (CT-SMAC)), tryptone bile glucuronic agar (TBX) and MacConkey agar (McCON). In addition, CHROMagarTM STEC was used for samples with a high level of competing bacteria. Any isolations were confirmed using PCR and/or biochemical tests. One isolate from every positive sample was further characterized by WGS including determination of AMR determinants, serovar and stx-subtype (see section 2.7). All confirmed STEC detections were reported promptly to the FSA.

2.3.5. Detection and enumeration of indicator E. coli

Detection of indicator E. coli was carried out by plating the enrichment broth on TBX with incubation at 44 °C for 22 h ± 2 h. Enumeration of indicator E. coli was carried out by plating the RPF sample meat homogenate/swab on TBX, with incubation at 30 °C for 4 ± 1 h followed by 44 °C for 21± 3 h, using an in-house method equivalent to ISO 16649-2:2001 (International Organization for Standardization (ISO), 2001).

2.3.6. Detection of ESBL-, AmpC-, and carbapenemase-producing E. coli and E. coli with resistance to colistin

For detection of antimicrobial-resistant E. coli, the methodology followed the EU protocol for the isolation of ESBL-, AmpC- and carbapenemase-producing E. coli (European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), et al., 2019). Detection of E. coli with resistance to colistin was performed as described in a previous FSA report (Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA), 2020). In brief, each enriched homogenate was plated after incubation onto MacConkey agar containing 1 mg per L cefotaxime (McC-CTX) for detection of ESBL-producing, AmpC-producing or both ESBL- and AmpC-producing E. coli (hereafter referred to as ESBL/AmpC-producing E. coli), ChromID® CARBA SMART Agar (CARBA) for detection of carbapenemase-producing E. coli (ChromID OXA-48 was not used as this agar was not in routine use in the UKHSA FWEMS laboratories as inadequate validation data were available at the time of the study) and MacConkey agar containing 2 mg/L colistin (McC-COL) for detection of E. coli with resistance to colistin. The CARBA plates were incubated for 18-22 h at 37 ± 1 °C and the McC-CTX and McC-COL agars at 44 ± 0.5 °C for 18-22 h. Up to three single presumptive E. coli colonies (lactose fermenters on McC-CTX and McC-COL and burgundy colonies on CARBA were assumed presumptive) from each of these agars were picked and plated onto the same stated agars to ensure purity. One isolate was then used to confirm E. coli by identification by MALDI-ToF and/or biochemical tests. The isolates were confirmed not to carry a stx gene using the PCR described on section 2.2.3 for any samples with a stx positive enrichment broth prior to isolate referral (2.5).

2.4. Detection and enumeration of Campylobacter

Detection and enumeration of Campylobacter was based on the ISO 10272 method although a secondary detection plate was not included (International Organization for Standardization (ISO), 2017a). For enumeration one mL of meat-BPW homogenate was plated across three standard sized modified charcoal cefoperazone deoxycholate agar (mCCDA) plates. For detection of Campylobacter, a 25 g portion of meat homogenate was diluted 1:9 in Bolton broth and incubated microaerobically at 37 °C ± 1 °C for 5 h ± 1 h followed by incubation at 41.5 °C ± 1 °C for a further 44 h ± 4 h; for 25 mL of the outer packaging swab liquid 225 mL of Bolton broth was used. The enriched broth was plated onto mCCDA. All mCCDA plates were incubated in an microaerobic atmosphere at 41.5 ± 1 °C for 44 h ± 4 h. Suspect Campylobacter colonies were picked (and counted for the enumeration test) and sub-cultured onto blood agar and incubated in a microaerobic atmosphere at 41.5 ± 1 °C. Confirmation of Campylobacter genus and the identification of species was determined by MALDI-ToF.

2.5. Detection of MRSA

The updated method recommended by the EURL-AR was used to determine the presence of MRSA in samples (European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) et al., 2022). Samples were diluted 1:9 in Mueller–Hinton broth containing 6.5% sodium chloride and incubated at 37 °C for 18 h ± 2 h for enrichment. A 10 μL loopful of the enriched culture was then spread on BrillianceTM MRSA 2 agar and incubated at 37 °C for 22 ± 2 h. One presumptive MRSA colony (denim blue colonies) from each sample was sub-cultured onto a blood plate and incubated at 37 °C for 24–48 h to look for characteristic morphology and haemolysis. Greyish/yellowish colonies usually surrounded by a zone of haemolysis were subjected to MALDI-ToF analysis to confirm Staphylococcus aureus.

2.6. Isolate referral

Confirmed isolates were referred to appropriate specialist laboratories for further characterisation including AMR testing and storage in cryopreservation beads. Salmonella isolates were sent to the Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA) and Campylobacter and MRSA to the Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute Northern Ireland (AFBINI) for MIC testing (section 2.6.). One E. coli isolate from each positive test (enumeration or detection, resistant to cefotaxime, resistant to colistin and resistant to carbapenems) per sample was also sent to APHA for MIC testing (section 2.6). Isolates where the mcr1 gene was detected were also sequenced at APHA (section 2.7). Salmonella, Campylobacter, and STEC isolates were sent to the Gastrointestinal bacteria reference unit (GBRU) at UKHSA for WGS (section 2.7). MRSA and ESBL-/AmpC-producing E. coli isolates were referred for WGS to Antimicrobial Resistance and Healthcare Associated Infections (AMRHAI) reference unit at UKHSA (section 2.7.).

2.7. AMR testing of E. coli, Salmonella, Campylobacter and MRSA isolates

Isolates were screened against panels of antimicrobials to establish their susceptibility according ‘epidemiological cut-off values’ (ECOFFs) determined by the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). MIC values were obtained using the microbroth dilution technique on the Thermofisher™ Sensititre instrument. Plates containing a two-fold dilution series of antimicrobial compounds were used in accordance with Decision 2020/1729/EU (Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2020/1729 of 17 November 2020 on the Monitoring and Reporting of Antimicrobial Resistance in Zoonotic and Commensal Bacteria and Repealing Implementing Decision 2013/652/EU., 2020). These were EUVSEC2 and EUVSEC3 plates (Thermofisher™) for E. coli and Salmonella, and the EUCAMP3 plate for Campylobacter.

MIC for E. coli, Salmonella and Campylobacter isolates were interpreted using the ECOFFs specified in the 2020/1729 EU decision, and if not available then current EUCAST ECOFFs published were considered (Annex 1). MIC results were also interpreted using the current EUCAST ECOFFs to see if this affected the interpretation of the MIC result (European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), 2024). For E. coli and Salmonella isolates, the microbroth dilution testing used a panel of 20 antimicrobials (Annex 1). Determination of whether E. coli produced beta-lactamase enzymes (of which there are three main AMR phenotypes, AmpC-, ESBL- or carbapenemase-producers) and determination of ESBL/AmpC phenotypes were established according to EU guidelines (European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), 2024). These stipulate that the presence of ESBL-producing E. coli strains is determined as follows: Isolates resistant to one or both of cefotaxime and ceftazidime that also have an MIC of greater than 0.125mg/l against cefepime and also show a reduction in MIC of ≥ 8 fold against combined cefotaxime / clavulanate or ceftazidime / clavulanate when compared with the cephalosporin alone are considered to carry an ESBL. AmpC-phenotype isolates are resistant to cefotaxime or ceftazidime but also to cefoxitin and showed no reduction to MIC’s, or a reduction of less than three dilution steps for cefotaxime or ceftazidime in the presence of clavulanate. Microbroth dilution testing for Campylobacter isolates used the standard panel of six antimicrobials (Annex 1) and this involved testing isolates for resistance to chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, ertapenem, erythromycin, gentamicin and tetracycline according to the European standardized EUCAMP3 plate format.

E. coli isolates originating from McC-COL plates were tested for the presence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance genes mcr 1-5 using the real time PCR method published by the EURL for AMR (https://www.food.dtu.dk/english/-/media/institutter/foedevareinstituttet/temaer/antibiotikaresistens/eurl-ar/protocols/colistin-resistance/1_396_mcr-multiplex-pcr-protocol-v3-feb18.pdf) and those with a confirmed mcr gene were MIC tested.

Microbroth dilution testing for MRSA isolates was conducted using the standard panel of antimicrobials as advised by the CRL (Annex 2). Multidrug resistance (MDR) was defined as demonstrated phenotypic resistance to three or more classes of antibiotics tested (Magiorakos et al., 2012).

2.8. Whole Genome Sequencing

Salmonella, Campylobacter, STEC and MRSA isolates were sequenced at the UKHSA Genomic Service Unit on Illumina® HiSeq platform using Nextera® XT library preparations from DNA extracted on a QIAsymphony® instrument using a DNA DSP mini kit. Isolates were sequenced on the platform in rapid run mode to produce 100 bp paired end reads. Trimmomatic v 0.40) was used to quality trim FASTQ reads with bases removed from the trailing end that fell below a PHRED score of 30. The Metric Orientated Sequence Type (MOST) V 1 (Tewolde et al., 2016) was used for sequence type (ST) assignment and identification assigned using multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) databases. Microbial fine typing was achieved by utilising the high discriminatory power of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP). For SNP typing, a bioinformatics application, SnapperDB has been developed to quantify SNP relatedness and derive an isolate level nomenclature (Dallman et al., 2018). This applies single linkage clustering to describe an isolate’s position in the population structure of a given eBurst Group (eBG) (Dallman et al., 2018). A Snapper database is required for each eBG and therefore, this is applied to the most frequent eBG (Chattaway et al., 2023) or merging eBG that pose a public health threat (Chattaway et al., 2019).

AMR genes/mutations were determined using previously published pipelines (N. Davies et al., 2022; Painset et al., 2020). Genetic linking through pairwise SNP analysis (≤5 SNP single linkage cluster (SLC)) was used to establish genetic similarity between strains. Previous studies have shown that analysing strains at the 5 SNP threshold has been appropriate to detect closely related clones (Chattaway et al., 2023, 2019; Mook et al., 2018; Pearce et al., 2018; Waldram et al., 2018).

In terms of analysis of WGS data of MRSA isolates, the complete genome of a CC398, spa type t011 strain, SO385 (GenBank® NC_017333) isolated from a human endocarditis case was used as a reference genome. E. coli isolates where mcr-1 were confirmed were sequenced (long reads) at APHA as described by Sequence data were uploaded to the Short Read Archive (SRA) and are available under BioProject PRJNA248549.

2.9. Statistics

Fisher’s exact test was used to compare sample groups where relevant using an on-line calculator (Analyze a 2x2 contingency table) with a significance level set at 0.05. Binomial 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using a JavaStat on-line calculator (JavaStat – Binomial and Poisson Confidence Intervals).

3. Results

The results from the testing of 277 raw dog food and 103 raw cat food samples are presented below.

3.1. Sample and packaging data

Sample data was collected from the sampler’s report. A total of 50 brands were recorded for the 380 RPF samples tested. For the majority (40/50) of brands only one specific ABP premises code was recorded, and this was not shared with any other brand. For seven brands one ABP approval code was recorded, but the ABP code was shared with one other brand. For three brands more than one ABP was recorded, two of which stated two ABP codes each and one brand had three different ABP codes recorded.

For a very large majority of samples (365/380) the ABP approval code was registered for premises in the UK while for 14 samples, premises were registered in the Republic of Ireland and two samples were from one premises registered in the Netherlands.

The RPF samples tested consisted of a range of different meat and offal types which included beef, beef offal, beef tripe, boar, boar offal, chicken, chicken offal, duck, fish, game, goose, Guinea fowl, kangaroo, lamb, lamb offal, lamb tripe, offal, partridge, pheasant, pork, pork offal, rabbit, turkey, turkey offal and venison and samples contained 118 different combinations of these. Bone was also listed as content but often without specifying animal species origin. In samples with fish content declared this was always accompanied by a higher proportion of other animal content present. For the purposes of analysis in this study, the term ‘bovine’ content was applied for samples where any beef, beef offal and/or beef tripe was recorded; the term chicken where chicken and/or chicken offal was recorded; the term ovine where any ewe, lamb, lamb offal and/or lamb tripe was recorded and the term porcine where pork or pork offal was declared.

The packaging of some of the samples (n = 34) were damaged on arrival and resulted in leakage as samples defrosted and this affected 17 brands. Furthermore, some samples did not have leakproof packaging for example cardboard packaging being used and becoming leaky upon defrosting (Table 1).

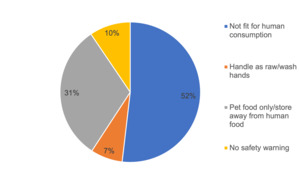

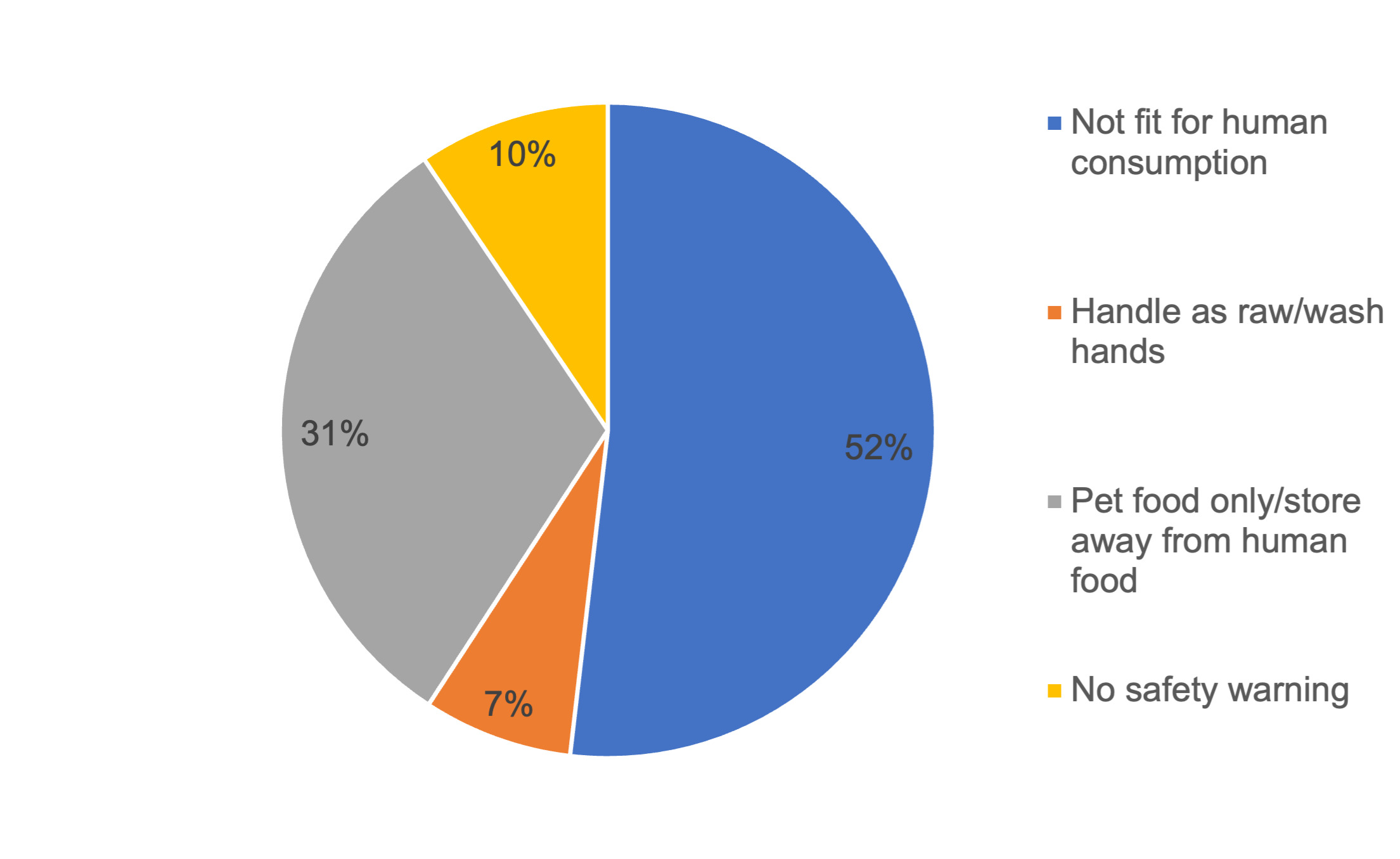

Information to consumers provided on the labelling of the raw dog and cat food packs was analysed (Figure 1). For a large majority of samples there was information on the labelling that stated the product was either not fit for human consumption or for pet food only. There was, however, no information as to whether the product was ‘not for human consumption’ or ‘use as pet food only’ for 17% of samples; there were no warnings displayed at all for 7% of samples and for 41% of samples there was no instructions to wash hands and clean utensils/surfaces after handling. In total 153 of 380 (40.3%) samples displayed the full information or wording equal to that effect: ‘Use as petfood only. Keep apart from food. Wash hands and clean tools, utensils and surfaces after handling this product’.

3.2. Detection of Salmonella, Campylobacter, STEC, MRSA and E. coli including AMR E. coli, in raw dog and cat food samples

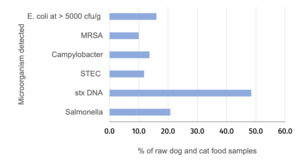

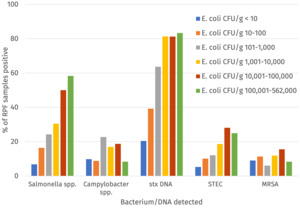

The percentage of samples positive for Salmonella, Campylobacter, STEC, MRSA and indicator E. coli at > 5000 CFU/g was calculated for the raw dog food (n = 277) and cat food (n =103) samples tested (Figure 2 and Table 2).

Salmonella was detected in 20.8% (with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 16.6% to 24.9%) of RPF samples with a higher prevalence in dog (24.2%; 95% CI 18.3% to 28.4%) compared to cat food samples (11.7%; 95% CI 6.8 to 20.4%) and this was significant (p-value = 0.011). All Salmonella detections were promptly reported to the FSA who informed the relevant authority for the ABP plant to enable further appropriate investigation. Campylobacter was detected in 13.7% (95% CI = 10.4% to 17.6%) of samples and there was no significant difference in the prevalence between dog (14.4%, 95% CI 9.9% to 18.2%) and cat food samples (11.7%, 95% CI 6.8% to 20.4%). Culture-confirmed STEC was detected in 11.8% (95% CI = 8.5% to 15.2%) of samples and there was no significant difference in the prevalence between dog (13.4%, 95% CI = 9.0%-17.0%) and cat food samples (7.8%, (95% CI 3.4% to 14.6%). PCR testing detected stx DNA in a higher percentage of samples (48.4%, 95% CI = 43.3% to 53.6%). MRSA was detected in 38 samples (10.0%, 95% CI = 7.2% to 13.5%) although this included two samples where isolates demonstrated resistance to cefoxitin but were negative for mec genes. If excluding these two isolates the percentage of samples positive for MRSA was 9.5%. MRSA were detected in a similar proportion of the raw dog and cat food samples. More than 5000 CFU/g of indicator E. coli was detected in 61 samples (16.1%, 95% CI = 11.6% to 19.0%) and E. coli at > 10 CFU/g were detected in 62.3% of samples (Table 2 and Annex 4).

The frequency of detection of pathogens and high levels of E. coli (those > 5000 CFU/g) was analysed in relation to the month of sampling (Table 3). The frequency of Salmonella detection was lowest (10.7%) in sampling months March to May and highest (28.9%) in sampling months June to August (Table 3). Detection of Campylobacter was lowest (10%) in winter sampling months and slightly higher across the remaining months. Detection of STEC was lowest (4.0%) in sampling months March to May and higher across the remaining months. The percentage of samples with MRSA was lowest (5.3%) in sampling months March to May and slightly higher across the remaining months. The percentage of samples with > 5000 CFU/g of E. coli was lowest (9.3%) in sampling months March to May and higher in the remaining sampling months.

The frequency of detection of pathogens was analysed in relation to area/manner of purchase (Table 4). Salmonella was detected at a similar frequency in samples purchased via UK on-line sales (22.8%) compared to samples bought in retail stores in England (21.4%) but detected in just 7.1% of samples obtained from stores in Northern Ireland. The percentage of samples with Campylobacter bought in retail stores in England or procured via UK on-line sales was lower compared to samples obtained from stores in Northern Ireland. Campylobacter was detected at a similar frequency in samples purchased via UK on-line sales compared to samples bought in retail stores in England. The percentage of samples with STEC bought in retail stores in England and Northern Ireland was slightly lower compared to samples procured via UK on-line sales. MRSA was detected at a similar frequency in samples purchased via UK on-line sales compared to samples bought in retail stores in England and Northern Ireland. The percentage of samples with > 5000 CFU/g of E. coli was similar whether samples were procured via UK on-line sales, bought in retail stores in England or obtained from stores in Northern Ireland. Additionally, in one sample obtained from a store in Wales, Salmonella, Campylobacter, stx DNA, STEC and MRSA were not detected.

The frequency of detection of pathogens or high levels of E. coli in relation to the type of animal content in samples was also analysed. Salmonella was most frequently detected in samples with any duck, venison, porcine and offal content and less often in samples with rabbit, fish or turkey content (Table 5).

Campylobacter was most frequently detected in samples with some duck or chicken content and less often in samples with venison, turkey, porcine or fish content. STEC was most frequently detected in samples with some duck, ovine or porcine content and less often in samples with any rabbit, fish, turkey and chicken content. MRSA was most frequently detected in samples with any porcine and venison content and less often in samples with rabbit, fish and poultry content. The percentage of samples with > 5000 CFU/g of E. coli was highest in samples with some porcine content and lowest in samples with rabbit, fish and turkey content.

Although this study was not designed to compare brands, rates of detection of pathogens were calculated for 18 brand/ABPs where more than 10 samples per brand were tested (Table 6). Salmonella was detected in at least one sample from 29 out of the 50 brands tested. The frequency of detecting Salmonella varied between 0 and 60% amongst the 18 brands where ≥10 samples were tested. Salmonella was detected in 19% of samples in the ‘other’ category (a category for all the brands where <10 samples were tested). Campylobacter was detected in products from 24 of the brands. Amongst the brands where 10 or more samples were tested, the highest percentage of samples positive for Campylobacter was 31%, while no Campylobacter were detected in five of the brands. Overall, stx DNA was detected in products from 41 out of the 50 RPF brands. The highest frequency of stx positive samples was a 100% and the lowest was 0% (for two brands) of the 18 brands where at least 10 samples were tested. Overall, MRSA was detected in products from 25 brands, with the highest percentage of 23% and the lowest at 0% amongst the brands where at least 10 samples were tested. Samples with > 5000 CFU/g of E. coli affected products from 27 brands overall. The highest percentage was 45% and the lowest at 0% amongst the brands where at least 10 samples were tested.

There was considerable variation in the counts of Salmonella in samples as determined from the Most Probable Number (MPN) enumeration test results (Figure 3, Annex 3).

For four samples the MPN result exceeded the upper limit of the test (theoretically this was ~10-30 CFU of Salmonella per 1 g sample). In three samples no MPN test was performed due to a technical error. For the purposes of analysis of MPN counts, a value of 10 CFU per g was assigned to the samples exceeding the upper limit of the test, resulting in an average level of 1.01 MPN/g, with a minimum, first, second and third quartile, and maximum of < 0, 0.036, 0.106, 0.33 and 11 MPN/g, respectively. The highest quantifiable level (11 MPN/g) was detected in a sample with S. Typhimurium and the next highest quantifiable level was a sample with S. Dublin with 4.6 MPN/g. In the four samples that exceeded the upper limit of enumeration, S. Newport (also containing S. London), S. Infantis, S. Derby and S. Typhimurium, were detected. These samples had bovine and turkey, bovine and chicken, porcine and turkey, and tripe content, respectively (Annex 3).

The level of Campylobacter in samples was above the lower limit of detection (10 CFU/g) of the enumeration method for 12 samples (3.2% of samples). In 11 of these samples (2.9%) counts varied from 10 to 70 CFU/g while one sample (0.3%) had 130 CFU/g of Campylobacter and this sample had chicken content listed.

Salmonella, Campylobacter, STEC, MRSA and/or > 5000 CFU/g of E. coli were detected in the majority (293; 77.1%) of RPF samples. In the remaining 87 samples with none of these organisms detected, stx DNA was detected in 27 resulting in a large majority of samples (320; 84.2%) where at least one of the following were detected: Salmonella, Campylobacter, STEC, stx DNA, MRSA or > 5000 CFU/g of E. coli. In 74 samples, two or more (meaning simultaneous detection) of the tests for Salmonella, Campylobacter, STEC, MRSA or E. coli at > 5000 CFU/g gave a positive result (Table 7). For example, Salmonella and E. coli >5000 CFU/g were detected in 15 samples, Salmonella and Campylobacter were detected in 12 samples, Salmonella and MRSA in 7 samples and Salmonella, STEC and E. coli >5000 CFU/g in 7 samples.

In 109 (28.7%) samples the statutory criteria in Annexes to assimilated Regulation 142/2011 (requiring absence of Salmonella and counts of Enterobacteriaceae to be ≤ 5000 CFU/g) were exceeded (assuming E. coli counts of >5000 CFU/g would also result in a count of Enterobacteriaceae of >5000 CFU/g as all E. coli are Enterobacteriaceae). In 48 samples Salmonella was detected but E. coli counts were ≤5000 CFU/g, in 30 samples E. coli counts were > 5000 CFU/g but Salmonella was not detected and in 31 samples both Salmonella and counts of E. coli of >5000 CFU/g were detected.

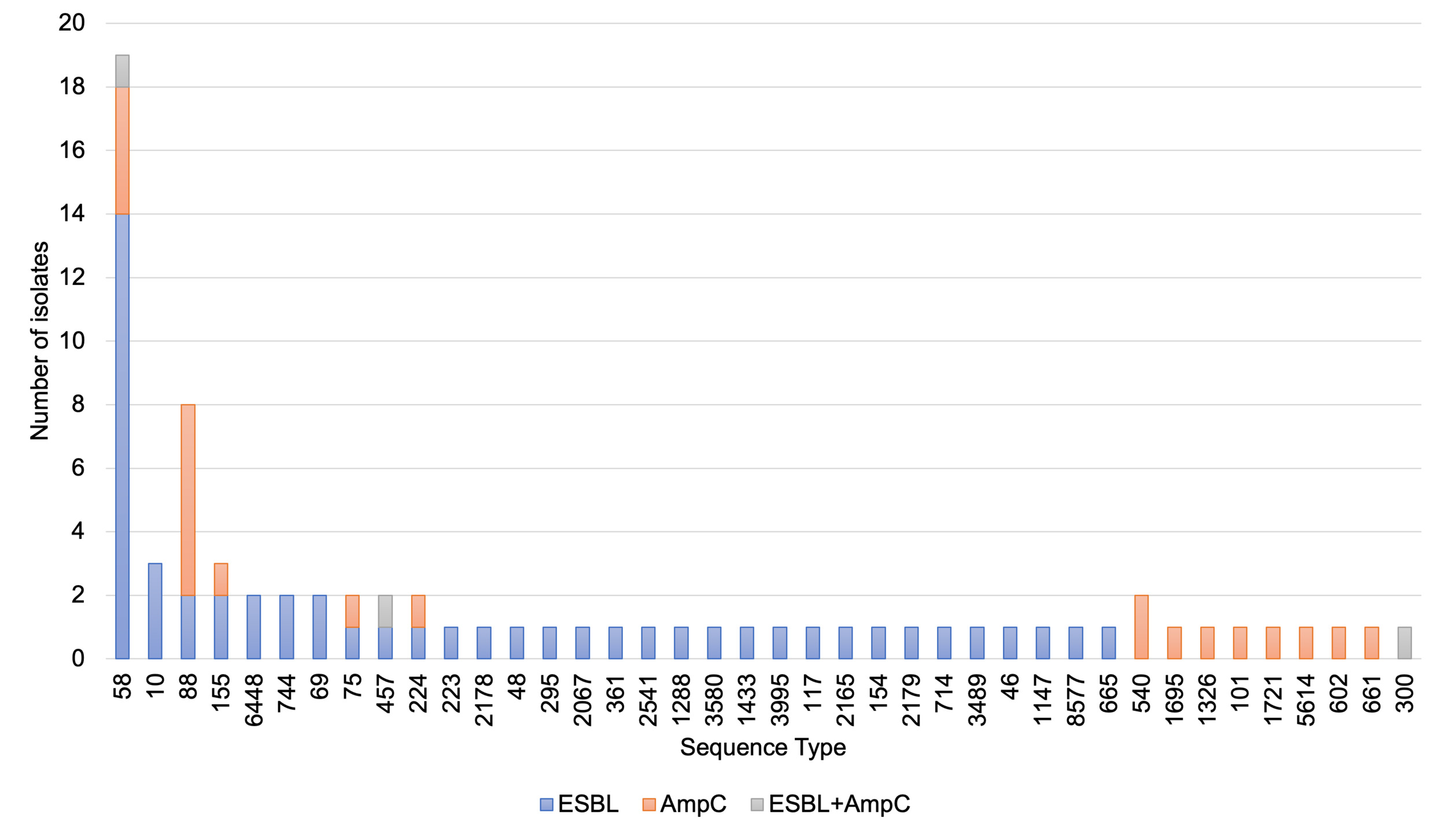

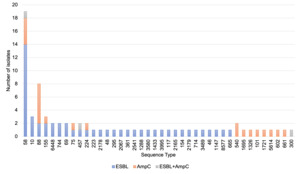

ESBL-/AmpC-producing E. coli were detected in 19.6% of samples with no significant difference in the percentage between the raw dog (21.5%) and cat (14.6%) food samples (Table 8).

Isolates were detected from CTX plates except one derived from a generic E. coli chromogenic agar (TBX) plate that was found to show resistance to cephalosporins and confirmed as an ESBL phenotype (despite no ESBL-/AmpC-producing E. coli detected from the sample via the ESBL/AmpC method from the CTX plate). In two samples where E. coli was recovered from CTX plates isolates were not MIC tested as they lost viability; if including these the percentage of samples with ESBL-/AmpC-producing E. coli would be 20.0% (76/380). ESBL-/AmpC-producing E. coli were detected at the highest frequency in samples with porcine and ovine content and least frequently in samples with rabbit (Table 9).

Most samples had mixed animal species content but for 21 of the samples with ESBL-producing E. coli a single animal species was listed and these included bovine (6), chicken (6), porcine (3), ovine (2), turkey (2), rabbit (1) and boar (1) contents.

Colistin resistant E. coli (with MIC = 4 mg/l) and harbouring the mcr-1 gene were detected in 1.3 % (95% CI = 0.4% to 3.0%) of samples including three dog and two cat food samples (Table 10).

E. coli with resistance to carbapenems were not detected in any of the samples tested using the CARBA agar as stipulated in the EU harmonised method.

3.3. Detection of Salmonella, Campylobacter and E. coli including AMR E. coli, from the outer packaging of raw dog and cat food samples

Of 189 outer packaging samples (137 from dog food and 52 from cat foods) tested, only one (0.5%) was positive for Salmonella and another sample (0.5%) positive for Campylobacter. The outer packaging of the dog food sample where Salmonella was detected had 3000 CFU of E. coli per outer packaging sample and no leakage of sample contents noted. In the dog food sample where Campylobacter was detected, sample leakage was noted but only 110 CFU of E. coli were detected in the outer packaging sample. Two (1.1%) outer packaging samples had > 5000 CFU of E. coli per pack (highest count was 20200 CFU per pack) and five (2.6%) had > 1000 CFU of E. coli per pack.

E. coli was detected significantly more frequently in outer RPF packaging samples where content leakage was noted (7/23; 30.4%; p = 0.003, Fisher’s exact test) compared to samples where no leakage was noted (10/140; 7.1%). An AmpC-producing E. coli was detected in one of 88 outer packaging samples tested (1.1%) whilst ESBL-producing E. coli or E. coli with resistance to colistin or carbapenems were not detected.

There was no indication that higher counts of E. coli were associated with a larger area of outer packaging (Figure 4).

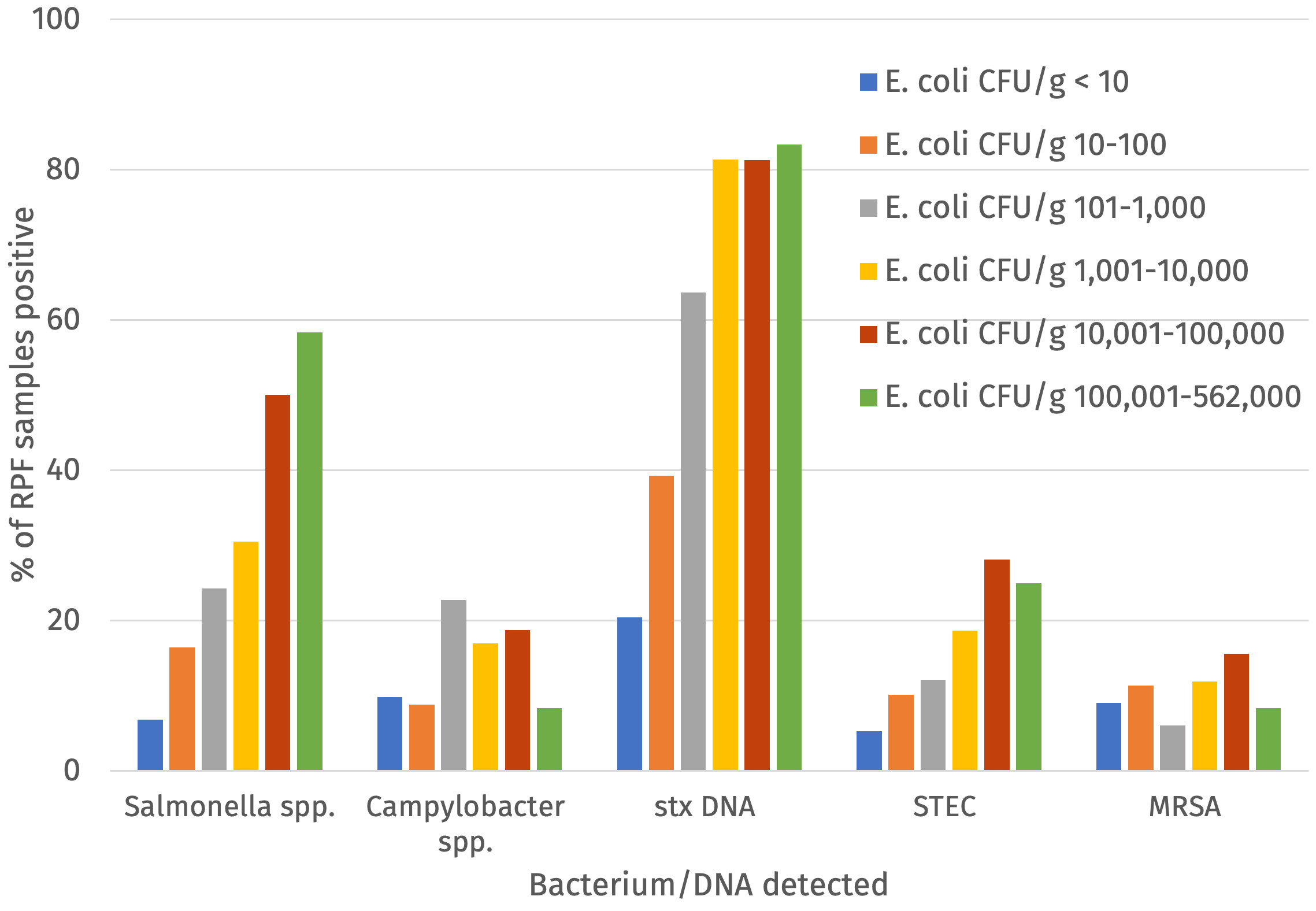

3.4. Indicator E. coli counts in relation to frequency of Salmonella, Campylobacter, STEC and MRSA detections in raw dog and cat food samples

Indicator E. coli was detected by enumeration and/or enrichment via TBX plates from all 380 raw dog and cat food samples and of these 248 were positive for indicator E. coli using the direct enumeration on TBX method (i.e. at levels of >20 cfu/g). The relationship between presence of Salmonella, Campylobacter, STEC or MRSA and the level of CFU/g of indicator E. coli was assessed (Figure 4 and Annex 4). There was an upward trend in the percentage of samples positive for Salmonella, STEC, stx DNA and Campylobacter (although slightly less) with increasing counts of E. coli but there was no clear trend for detection of MRSA (Figure 5).

Furthermore, using a threshold of > 5,000 E. coli CFU/g as an indication of the likelihood of detection of Salmonella, Campylobacter, STEC or MRSA, the following standard parameters were calculated: the sensitivity (i.e. the proportion of pathogen positive samples with > 5,000 E. coli CFU/g), specificity (i.e. the proportion of pathogen negative samples with ≤ 5,000 E. coli CFU/g), positive predictive value (PPV; i.e. the proportion samples with > 5,000 E. coli CFU/g positive for a pathogen), negative predictive value (NPV; i.e. the proportion samples with ≤ 5000 E. coli CFU/g negative for pathogens) and accuracy (i.e. the proportion of samples where according to the 5000 E. coli CFU/g threshold categorised correctly in terms of presence or absence of pathogen) (Table 11).

The specificity, NPV and accuracy was relatively high for all target pathogens, except for stx DNA where the NPV was lower. This may suggest a reasonably robust prediction based on a threshold of 5000 E. coli/g of absence of Salmonella, Campylobacter, STEC and MRSA. The sensitivity and PPV values were lower and would indicate an issue with a low confidence in positive results (meaning detections of E. coli at > 5000/g would not necessarily mean that Salmonella, Campylobacter, STEC and/or MRSA would be present), although the PPV was higher for detection of stx DNA. The accuracy (that is the correct classification of samples based on the 5000 CFU/g of E. coli threshold) varied between 0.79 and 0.62, with values for Salmonella, Campylobacter, STEC, stx DNA and MRSA of 0.79, 0.74, 0.79, 0.62, and 0.79, respectively (Table 11).

3.5. AMR and WGS results for pathogens and E. coli detected in raw dog and cat food samples

3.5.1. Salmonella

Salmonella was detected in 79 of the raw dog and cat food samples (20.8%) and in seven (1.8%) samples two different serovars were isolated. Thus, a total of 86 isolates from the samples were available for MIC testing and WGS. One S. enterica spp. diarizonae (S. diarizonae) isolate was not MIC tested as it lost viability but a fully susceptible AMR profile for this isolate was predicted from analysis of WGS data and this result has been included in the results presented below. The most frequently detected serotype was S. Typhimurium (including monophasic variants) detected in 16 samples followed by S. diarizonae (14 samples), S. Infantis (9 samples), S. Derby (7 samples) and S. Dublin (6 samples) (Table 12). Most samples with MDR Salmonella had S. Infantis or S. Typhimurium, in contrast no MDR was detected in samples exclusively positive for S. diarizonae.

From the majority of samples that were positive for Salmonella (75.9%, 60/79), the isolates were sensitive to all antimicrobials tested. The percentage of isolates with resistance to individual antimicrobials ranged from 0 to 10.5% (Table 13). Salmonella isolates were most commonly resistant to ampicillin (9.3%), ciprofloxacin (10.5%), nalidixic acid (9.3%), sulfamethoxazole (10.5%) and tetracycline (10.5%).

Resistance to colistin was detected in 5.8% of isolates although none were positive for mcr genes. None of the Salmonella isolates were resistant to amikacin, gentamicin or meropenem and resistance to azithromycin, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, tigecycline and chloramphenicol was low (1.2% of isolates).

Isolates with resistance to at least one antimicrobial was detected in 10 samples and MDR was detected in seven (8.9%) and this included one sample with a S. Infantis isolate with an ESBL phenotype.

Results from phenotypic resistance determined by MIC testing were generally in agreement with the genetic determinants for AMR detected by analysing WGS data although genetic determinants associated with resistance to colistin, tigecycline and some aminoglycosides were not fully determined (Table 14). Further detailed bioinformatics analysis would be needed to elucidate this and was beyond the scope of this project. The detailed results of MIC and analysis of WGS data of all Salmonella isolates has been provided in Annex 5. Amongst the 86 isolates, resistance to azithromycin was detected in one isolate of four S. Indiana detected (Table 14). Resistance to ciprofloxacin was detected in S. Infantis (4/9), S. Indiana (2/4), S. Enteritidis (1/2) and S. Dublin (1/6). A MDR phenotype was detected in eight isolates and included six different AMR profiles and with resistance to between three and six antimicrobial classes and included the ESBL-producing S. Infantis isolate. Various animal content was recorded for the samples where resistant Salmonella isolates were present and included chicken (5 samples), bovine (5 samples), duck (2 samples), ovine (1 sample), porcine (1 sample) and turkey (1 sample).

No change in resistance profiles for any of the Salmonella isolates was noted had the current EUCAST ECOFFS been applied instead of the 2020 EU CID ECOFFs.

For 17 of the 79 (22%) samples that were positive for Salmonella, the isolate clustered with one or more isolates from another sample (meaning isolates were in the same Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) SLC with a 5 SNP threshold) (Table 15).

Four samples harboured the same S. Infantis SIt5a strain and were detected in samples from different brands/ABPs of which three listed chicken content and one duck content. The same S. Typhimurium STt5b strain was detected in three samples from different brands/ABPs with one sample listing chicken content, another ovine content and the third ovine and chicken content. Two samples from different brands/ABPs harboured a S. Typhimurium STt5c strain and both had bovine content as the only animal content declared. Two samples had a S. Typhimurium STt5d strain, from different brands/ABPs, one with tripe content the other with bovine content. A fourth S. Typhimurium STt5e strain was detected in two samples, from different brands/ABPs with both samples having duck listed as the only animal species in contents. The same S. Dublin SDt5f strain was detected in two samples from two brands, one with duck, bovine and ovine content and the other with chicken and bovine content. Finally, a S. Hadar SHt5g strain was detected in two samples from different brands, one with bovine, duck and venison content the other solely with duck content. In total, for 5/7 strains there was some common animal species in the samples suggesting animal content from the same source may have been used to produce products by different brands/ABPs.

One outer packaging sample was positive for S. Anatum; the same (ie. the two isolates were in the same 5 SNP SLC) S. Anatum strain was also detected in the raw dog food contents from the sample.

All the serotypes of Salmonella detected in the raw dog and cat food samples have previously been detected in samples from human cases. Further work is on-going to investigate how the isolates relate to Salmonella from human cases and details of possible exposure routes.

3.5.2. Campylobacter

Campylobacter was detected in 52 RPF samples. C. jejuni (exclusively) was recovered from 23 samples and C. coli (exclusively) also from 23 samples while both species were detected in five samples; in one sample C. hyointestinalis was detected. Isolates from 48 of the 52 samples were subjected to AMR testing as for two samples with C. jejuni and another two with C. coli, isolates could not be recovered from frozen storage.

AMR was determined for 27 C. jejuni (this included two distinct C. jejuni from one sample) and 26 C. coli isolates (Table 16; Annex 6).

There was an excellent agreement between the phenotypic AMR results obtained by MIC testing and AMR results predicted from WGS data, although no prediction of resistance to ertapenem based on WGS data was attempted since no validated prediction of determinants for ertapenem was available. Resistance to ciprofloxacin was observed in 44.4% of C. jejuni isolates and all of which harboured a genetic determinant gyrA (T86I) known to confer resistance to fluroquinolones. Resistance to tetracycline was detected in 40.7% of C. jejuni isolates with the tetO gene detected in all of these. Using the proposed resistance threshold for ertapenem, resistance was observed in 25.9% of C. jejuni isolates.

Amongst C. coli isolates, 34.6% were resistant to ciprofloxacin and these harboured the mutation in the gyrA (T86I). Resistance to tetracycline was detected in 50.0% of C. coli isolates consistent with the detection of a tetO gene in these isolates. Resistance to ertapenem was detected in 23.1% of C. coli isolates.

All isolates were sensitive to erythromycin and gentamicin and none of the genetic determinants known to confer these phenotypes were detected. Just over half (51.9%) of the C. jejuni isolates and 30.8% of C. coli isolates were susceptible to all antimicrobials tested and no genetic determinants for resistance to ciprofloxacin or tetracycline was detected in these isolates.

MDR (to ciprofloxacin, ertapenem, tetracycline) was detected in 22.2% of C. jejuni isolates and in 11.5% of C. coli isolates. Based on analysis of WGS data, a determinant likely to confer resistance to streptomycin was detected in one C. coli isolate but no phenotypic test was done for this antimicrobial. Findings on ertapenem resistance should be interpreted with caution as the ECOFF for ertapenem used by EFSA is still under discussion and there is not yet a validated threshold for resistance to ertapenem established by EUCAST.

Within C. jejuni 17 different MLST ST and within C. coli 18 different MLST STs were detected (Table 17 and Table 18, respectively).

Some associations between ST and AMR were noted for C. jejuni. All C. jejuni ST464, ST2254, ST6175, ST9897 and ST12327 isolates were resistant to ciprofloxacin and harboured the gyrA (T86I) mutation known to confer this phenotype. These isolates were also all resistant to tetracycline with ST464, ST9897 and ST12327 positive for the mosaic tet(O/32/O) gene type but ST2254 and ST6175 isolates had the standard tet(O) gene type. In contrast, all C. jejuni isolates belonging to CC-42, CC-45, CC-48, CC-61, CC-283 and CC-443 were sensitive to ciprofloxacin and tetracycline. For C. coli isolates AMR profiles varied for STs.

The type of animal content in samples with AMR C. jejuni or C. coli isolates varied considerably (Table 19), nonetheless chicken (7/9 samples) and bovine (7/9 samples) content was common in samples with MDR isolates. MDR isolates were detected in products from eight different brands/ABPs of the total of 24 brands where any Campylobacter were detected.

One outer packaging sample was positive for C. jejuni but a C. coli isolate was detected in the contents from this sample.

Examining the PubMLST database confirmed that all the STs detected have previously been isolated from human cases. Further work is on-going to investigate how the isolates relate to Campylobacter from human cases and details of possible exposure routes.

3.5.3. STEC

Of the 45 RPF samples where STEC was detected, isolates from 44 samples were subjected to WGS analysis which included determination of genetic determinants predicted to confer resistance to antimicrobials (Annex 8). AMR in the STEC isolates was predicted from WGS data as phenotypic AMR testing was not possible due to constraints on the higher containment level 3 laboratory space required. Overall, 32 different serotypes were identified among the 44 STEC (Table 20). Serotypes occurring more than once were O146:H21 (n = 6), O100:H30 (n = 6), O8:H9 (n = 2), O8:H19 (n = 2), O38:H26 (n = 2) and O-unidentified:H28 (n = 2). STEC O157:H7 was not detected.

Analysis of the WGS data revealed that eight STEC isolates carried stx1 genes only: stx1a (n = 1), stx1c (n = 6) and stx1d (n = 1). In 24 isolates solely stx2 genes were detected: stx2a (n = 1), stx2b (n = 6), stx2d (n = 5), stx2e (n = 2), stx2g (n = 9). Four samples had isolates with combinations of stx2 genes: stx2a and stx2e (n = 2), stx2c and stx2d (n = 1), stx2b, stx2c and stx2d (n = 1). In 13 isolates combinations of stx1 and stx2 genes were detected: stx1c and stx2b (n = 11), stx1a and stx2a (n = 1) and stx1a and stx2d (n = 1). There was considerable diversity in the STs detected and 41 different STs were determined. None of the isolates belonged to the same 10-SNP SLC indicating that none of the isolates were closely related.

Overall, 40 of the STEC isolates (88.9%) were predicted to be susceptible to all antimicrobials. Two isolates (4.5%) had genes (blaTEM-1) predicted to confer resistance to β-lactams. Two isolates (4.5%) had tetA and on tetM, predicted to confer tetracycline resistance. Two isolates (4.5%) had genes expected to confer sulphonamide resistance with sul-1 and sul-2 detected in both isolates. A dfrA-1 gene known to confer resistance to trimethoprim was detected in two isolates (4.5%). Two isolates (4.5%) had genes expected to confer resistance to streptomycin, one with strB in combination with another gene (aph(6)-Id) known to confer resistance to an aminoglycoside and one with aadA-1b in combination with another gene (ant(2’')-Ia) known to confer resistance to another aminoglycoside. Two isolates (4.5%) contained a mutation in the gyrA gene (S83L) that is known to confer resistance to quinolones including ciprofloxacin. Genes predicted to confer resistance to carbapenems were not detected in any of the STEC isolates. In two isolates (4.5%) genetic determinants for resistance to more than three classes of antibiotics were detected (deemed MDR); one ST10 isolate had the AMR profile blaTEM-1, strA, strB, aph(6)-Id, gyrA(S83L), mph-B, dfrA-1, sul-1, sul-2, tetA and floR predicted to confer resistance to ampicillin, aminoglycosides, quinolones, macrolide, trimethoprim, sulphonamides, tetracycline and chloramphenicol; the other MDR ST329 isolate had a aadA-1b, ant(2’')-Ia, mph-B, gyrA(S83L), dfrA-1, sul-1,sul-2, tetM and floR profile expected to confer resistance to aminoglycosides, quinolones, macrolide, trimethoprim, sulphonamides, tetracycline and chloramphenicol.

3.5.4. MRSA

Phenotypic resistance to cefoxitin was confirmed for 38 Staphylococcus aureus isolates and antimicrobial resistance profiles determined by MIC testing showed that all isolates were phenotypically resistant to penicillin with the exception of one (Table 21 and Annex 8). There was a high rate of tetracycline resistance and around half of the isolates were resistant to macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin antibiotics. Resistance to erythromycin, clindamycin and synercid was detected in 15 isolates (39.5%). Two isolates (5.3%) were resistant to erythromycin and clindamycin but were sensitive to synercid. Three isolates were resistant to clindamycin and synercid but were sensitive to erythromycin. All isolates were susceptible to vancomycin and linezolid. Only three isolates (7.9%) were resistant to mupirocin.